High-quality handcrafted acoustic guitars don't grow on trees.

Well, they do—sort of—but it takes more than a magical harvest to end up with one. Handcrafted acoustic instruments require months of labor, patience, and quiet determination to assemble. They aren't mass-produced. They can't be. And that explains why they cost so much. For example, the starting price, sans bells and whistles, for the instruments featured in this roundup is between $5,000 and $14,000. Lutherie is a test of endurance and not for the impulsive or easily distracted—leave that to the musicians. Builders are focused, careful, and long-term thinkers.

They also have strong opinions.

No issue, at least among the builders featured here, shows greater disparity than their embrace of machines and technology. Some builders rely heavily on CNC (computer numerical control), CAD (computer-aided design), laser-cutting and engraving tools, and high-precision tooling. Others use a band saw and router, preferring to do most of their work with hand tools and simple sanders. But despite their preferences and opinions, they aren't in the dark about alternative viewpoints. As U.K. builder Roger Bucknall of Fylde Guitars puts it: “It's difficult nowadays to draw a hard line between hand-making and machine-making."

Our featured builders also disagree about bling. Some build instruments that glisten with museum-quality artwork, intricate inlays—on fretboards, headstocks, rosettes, bindings, and backs—and elegant curves and bevels. Others offer simple, no-nonsense workhorses and have no intention of doing otherwise. Their business models differ as well and range from modest, 17-person factories to simple one-person operations. Most, at some point, have tried both.

For the most part, these differences are superficial. The art of guitar making has much common ground.

One shared skill is voicing tops, backs, and sides. Most builders don't choose wood just for its grain pattern or color, although aesthetic considerations are usually considered. Wood's most important component is sound. A skilled luthier will spend a good part of a day gently taping an unfinished top, listening for fundamental pitches and accompanying overtones, and then handcarving and reshaping its braces to bring out its resonant frequencies. What's more, every piece of wood is different. Discovering a material's—and ultimately an instrument's—unique sonic qualities is what makes playing a rich and rewarding experience.

It's also what distinguishes one builder from another.

The builders featured here also share an obsession with wood. They buy wood, usually more than they'll ever need—even whole trees, when possible—and store, age, dry, cut, and acclimatize it, usually for years and years, until they feel it's suitable for a guitar. To paraphrase instrument luthier Isaac Jang, “most builders suffer from wood acquisition syndrome."

We spoke with five builders about their instruments, techniques, building philosophies, opinions, and innovations. Their dedication and passion is palpable, and their hard work is obvious in the instruments they make. Brace yourself (pun intended) and get ready to learn, mostly in the words of the builders themselves, about a world you might know little of, but which is essential to the music you make.

Dana Bourgeois left a career in the art world for a career crafting tools for the music world.

Bourgeois Guitars: Gauging the Velocity of Sound

Dana Bourgeois, based in Lewiston, Maine, didn't start out to be a luthier. “I was an art history major," he says. “After college, I worked for an art museum and I was interested in going to graduate school in museum science. On the side, I knew musicians and guitar players. I was building a guitar here and there, and repairing guitars. Back in those days, everyone played guitar, but very few people were working on guitars. I had people bringing guitars to me, asking, 'Can you fix this?' One day, I had this epiphany that I liked people in the music world more than I liked people in the art world. I had enough business to quit my job and go off on my own, which is what I did." But he was still years away from establishing his own company, Bourgeois Guitars.

He started working at the Music Emporium in Cambridge, Massachusetts (now located in Lexington, Massachusetts), where he befriended Eric Schoenberg, one of the store's owners, and they eventually founded Schoenberg Guitars. “It was the very beginning of the renaissance of the OM guitars," Bourgeois says. “The Music Emporium was ordering OMs through Martin's custom shop as custom instruments. Eric and I put out one of the first production OMs. Ours also featured a cutaway and we did that for a while. I would go down to Martin—they would build in batches of 20—and I would voice the tops down at Martin." Doing repairs also gave him exposure to vintage instruments. “The exposure I had to vintage guitars through the Music Emporium was invaluable. At any time, I might have what today would be a million dollars' worth of instruments in my shop."

Bourgeois created this L-DBO model for the Dixie Chicks' Natalie Maines. Not content to simply paint a guitar white, Dana drew inspiration from old electric guitars and created a finish that let the grain show through.

Photo by Tim Whitehouse

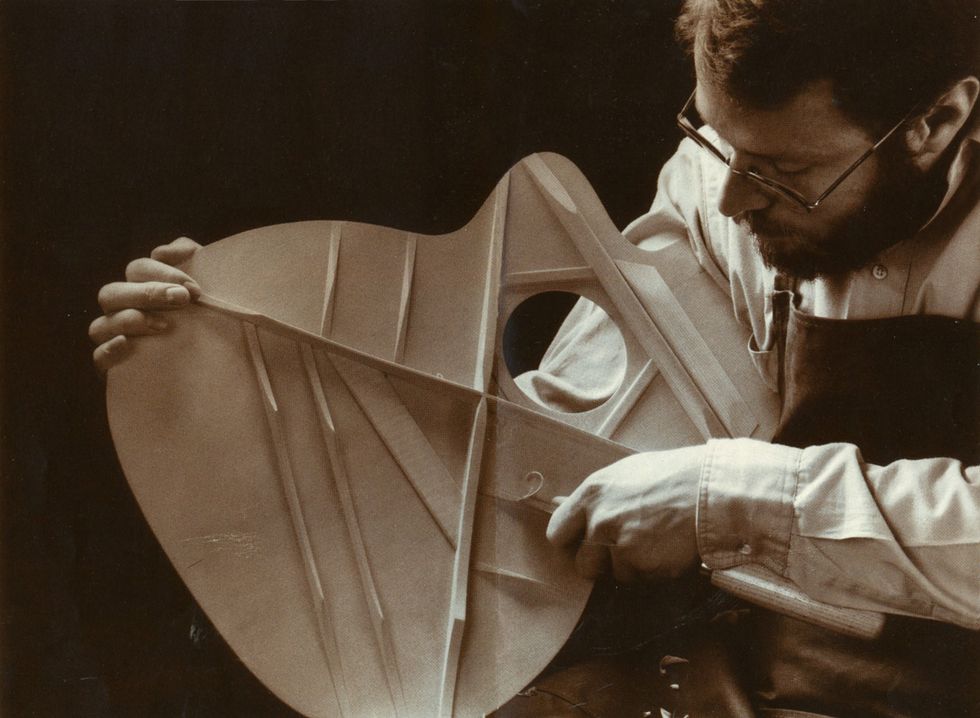

That exposure, plus years of experience, has made Bourgeois a master voicer. (Below watch him voice a top.) He voices every instrument his company, which he founded in 1992, sells. “My approach is to get as many different resonant frequencies as possible out of the guitar top and back," he says. “My philosophy of building, regardless of the size of the guitar, is to get good balance and clarity: string-to-string and note-to-note balance.

I want a strong fundamental and a strong series of overtones as opposed to a sketchy series of overtones. My approach to voicing is to build within a very narrow range of flexibility. The top is built for a narrow range of flexibility both across and along the grain. It starts out stiff and as you work your braces, you work down to the desired level of flexibility. There is no way that you're going to get every note to be equally strong. It simply doesn't happen that way. If you did, every guitar would sound like a synthesizer. They all have their own individual characteristics. The key is that every piece of wood is a little bit different. You have to work with what you've got and try to bring out the greatest variety."

Bourgeois is a master voicer of acoustic guitar tops. He's shown here in the 1980s, when he worked as a builder at Schoenberg Guitars with Eric Schoenberg.

Bourgeois Guitars are known for their Aged Tone instruments. These guitars are built with torrefied wood, a special “aged" lacquer, and an animal protein glue made from fish bones and cartilage (as opposed to horse hooves or rabbit hide). “Torrefaction is cooking wood in an oxygen-free environment," Bourgeois says. “The idea is to cook off the volatiles in the wood—sugars, oils, pitches, resins—that would normally oxidize over many decades. If you do it right, you increase the stiffness of the wood and lower its weight. You increase the stiffness-to-weight ratio, which is the formula for velocity of sound. That sort of broken-in guitar sound that everyone talks about in an older guitar is really about an immediate explosive response and the ability to generate higher overtones. When you play a note, you play the fundamental tone and the wood will generate higher overtones unless it is damped. The stuff that's cooked off has a damping effect. Torrefaction is a way of making a guitar that breaks in a lot sooner." A new finish has a damping effect as well. “Lacquer takes 25 years or so to fully cure. It's kind of like concrete. It never stops curing. Together with our finish supplier, we helped develop a finish that has the hardness and density qualities of an older lacquer finish. If it's applied thinly enough, it will not damp the sound of a new guitar."

“The key is that every piece of wood is a little bit different," Bourgeois says.

Bourgeois builds about 400 guitars a year. He has 17 employees, 12 of whom are in the shop—and that includes him. “I am the owner and CEO of a small company," he says. “A lot of my peers don't spend any time in the shop any more. I spend most of my time in the shop, and that's the way I like it."

Roger Bucknall built his first guitar when he was 9 years old—almost 70 years ago.

Fylde Guitars: Blending Intuition and Engineering

Roger Bucknall built his first guitar when he was 9 years old—almost 70 years ago. “I've been making guitars ever since," he says. “Sometimes as a hobby, and since about 1973 as a professional guitar maker." His list of clients reads like a who's who of fretboard royalty. “Pete Townshend, Cliff Richard, Gordon Giltrap. Al Di Meola bought one from me recently. Eric Bibb has about 11 of mine, I think. Davey Graham had one of mine. Lisa Hannigan, John Renbourn, Ritchie Blackmore, Andy Irvine, Fairport Convention, Mick Jones—everybody."

Fylde Guitars is named after the Fylde coast of Lancashire in Northwestern England, just north of Liverpool, where Bucknall first set up shop. In 1996, he moved the business to Penrith, in England's Lake District.

—Roger Bucknall

Bucknall has a degree in engineering from the University of Nottingham and used those theories in his early designs—although nowadays he relies mostly on intuition. “In the early days, I used a lot of the mathematics that I learned in engineering," he says. “I do it more by instinct now. I was very intent upon using the theory in the beginning. As time has gone on I've abandoned the theory and just followed instinct."

He also does almost everything by hand. “For the size of the business we are, I think we do more work by hand than just about anybody else. I have a CNC machine. I bought it 20 years ago and I've still not used it. I experimented, tried to make fingerboards and truss rod covers. All it's ever made for me are truss rod covers, which I can buy for a few pence. So that was an expensive mistake. I can shape a neck quicker by hand than a CNC machine can."

Bucknall could be called a tree hoarder. Acquiring quality woods for his guitars, even whole trees, is a central focus.

Central to Bucknall's approach is finding, drying, and storing—some would call it hoarding—the best woods available. “Wherever possible, we buy the whole tree," he says. “I've bought whole trees from America. I've bought whole trees from India. We bring it over. We have it cut. We dry it. We cut it again and we dry it again. I have a philosophy that we don't use any piece of wood unless I've had it for at least two years and it's been kiln dried first. It's very important. I don't use any fresh wood that I've bought from a supplier. It has to be my own." Being based in the Lake District, a place notorious for its dampness and rain, is not naturally conducive to drying woods—but that's only strengthened his resolve. “We have a specially built workshop with environmental control. I can control the conditions very accurately, which somebody else in a different part of the country probably couldn't do, because they haven't invested quite as much money in the building."

Fylde Guitars are very specific about tone, not aesthetics. “If I make a guitar with lots of inlay on, I could have made two guitars in that time," Bucknall says.

Bucknall's guitars have a specific sound—one that he's particular about. “I don't like guitars that shout," he says. “I like a guitar to be fairly gentle. I think a lot of modern makers now make guitars that really are quite loud and have a huge impact—which is very impressive when you're in the context of an exhibition or in a shop, but when you take the guitar home, play it quietly, and really listen to it, it's missing the actual tone. Volume and bass are not the same as tone. They are just two aspects of tone. The rest of tone comes from the structure." He also takes a plain-Jane approach to inlay. “If I make a guitar with lots of inlay on, I could have made two guitars in that time. I'd rather make two guitars and get them onstage and working. That's what I'm trying to do."

But more than anything, Bucknall values the relationships he makes with his clients. “Every single time I make a guitar, I make a new friend," he says. “We meet, talk it through, agree what needs to be made, and that person remains a friend for the rest of my life."

“Most builders suffer from wood acquisition syndrome," says Isaac Jang, who is not immune to the phenomenon.

Isaac Jang: Geometry Adds Complexity

Isaac Jang, based in Hollywood, California, builds handmade, ergonomic, elegant guitars. He's the youngest builder profiled here and only recently finished his apprenticeship with Kathy Wingert.

“I got in touch with Kathy and said, 'I would like to study guitar making with you,'" he relays. “I was around 18-years-old at the time and she said, 'Since I have children your age, I'm going to give you my mom talk: You have to be in school, you have to build a few guitars, and you have to work in a repair shop.'"

—Isaac Jang

He took her advice. He studied with Bryan Galloup at the Galloup School of Guitar Building and Professional Guitar Repair in Big Rapids, Michigan, built a few guitars, and got a job at Westwood Music in L.A., servicing A-list musicians—not that he knew who they were. “I moved from Korea and I wasn't aware of that many people in the music scene. I was just into guitars. Later, some of my coworkers were like, 'Do you know who that is?' I said, 'I'm not sure.' They said, 'Look him up.' I looked him up and I was like, 'David Crosby. He's a big name. Wow!' It seemed like that happened all the time with me." He also reconnected with Wingert. “I got in touch with Kathy. I said, 'This is Isaac, do you remember me? I'd like to show you my guitars that I built.' I started working with Kathy. I studied with her for about 10 years."

Quality over quantity is Jang's building motto. Rather than increase production, Jang works as a one-man operation with a focus on improving his skill and making the best guitars possible.

Some of Jang's builds feature an innovative and ergonomic cutaway—he calls it a bendaway—borrowed from Japanese master builder Mitsuhiro “Micky" Uchida. “I looked at different cutaway designs," he says. “There is the Venetian cutaway. There is a Florentine cutaway. I wanted to play with it a little bit. I came across Micky Uchida—he is an old-school luthier from Japan—and I asked him if it would be okay to use his design. He said, 'Of course. Perfectly fine.' The idea is to use the minimum amount of space from the guitar's body, to still have access to the upper frets, but without losing too much of the body or extra volume. I have a couple of guitars I'm working on now with slightly more of a bendaway—another two frets in or so. It seems to feel pretty good, pretty comfortable, and people seem to like it."

Jang apprenticed with luthier Kathy Wingert for a decade.

When viewed from the side, some of his guitars are wedge-shaped: thinner at the top than at the bottom, which is a design borrowed from California builder Linda Manzer. It's called a Manzer Wedge. “The big advantage is ergonomics," Jang says. “You're able to have a little bit deeper body without sacrificing comfort. Plus, having a slightly different geometry in the guitar body adds a little bit more complexity in the guitar box."

Some of Jang's builds feature an innovative and ergonomic cutaway, as shown on this OM model. He calls it a bendaway—borrowed from Japanese master builder Mitsuhiro “Micky" Uchida.

Jang's philosophy is wood-centric. “I like to have the wood speak for itself," he says. “I'm more of a designer who manipulates some parts to let the wood sing. My wood usually comes dried from the supplier, but I like to let it acclimate in my space for at least a couple of years before I start to use it. When I first started getting into guitar making, I started investing in wood. I bought wood anytime I had a little savings, so I actually have stacks that are about nine or 10 years old. Then it's one of those things: guitar wood acquisition syndrome. I always extend my stack. It's an addiction."

In addition to teaching lutherie at Musicians Institute Guitar Craft program in L.A., Jang's building goals are long-term. “My current objective for the next five-to-10 years is to refine every detail and every part of guitar making," he says. “I'm not looking to increase the number of guitars I make. I would prefer to really dial it in—focusing on the quality and the individual instruments that come out of my shop."

Kevin Ryan's background in carpentry and aerospace helped him in his precision with guitar building.

Ryan Guitars: From Carpentry to High Tech

Ryan Guitars, the brainchild of SoCal builder Kevin Ryan, is a synthesis of tradition and technology. Given his background, that's what you'd expect. “Out of high school, I was a carpenter framing houses," Ryan says. “I moved to California in 1987, got a job working in aerospace, and that eventually landed me in [my company's] aero-science laboratory, which was essentially a wind tunnel. As carpenters, we think in 16ths of an inch or with tape measures, but in aerospace we thought in thousandths of an inch. Precision, thinking in three dimensions, new tooling, new ways to do stuff—aerospace manufacturing is a whole different mindset. It was so helpful for me and my guitar building career."

That synthesis is reflected in Ryan's choice of tools. “If you didn't know any better, we would look almost like a low-tech shop," he says. “Everything is made from wood and MDF [medium-density fiberboard] superglued together—there's all kinds of stuff like that.

and laser were here." —Kevin Ryan

The high-tech part is having the huge CNC machine, the laser, and lots of precision tooling we've made on the laser and CNC machine. Technology allows us to do things we couldn't do before and to do them to a level of precision that was unthinkable before CNC and laser were here."

Ryan's method of cutting fret slots is an example of something previously impossible to do. “The old way fret slots were cut was with a table saw," he says. “You would saw the slot all the way through. Also, picture a radius fretboard: the slot is deeper in the middle than it is at the ends because the saw cut is straight while the top of the fretboard is radius. I invented a system where, first of all, the slot doesn't go all the way through like it has to with a saw. I drop down what we call 'blind cut' with a 20/8000th end mill in an air turbine so it doesn't go to the edge of the fretboard. It starts in from the edge and it stops in from the other edge. I don't have to glue binding on there, because the binding is the fretboard. It never got slotted at the end. Also, the slot is cut parallel with the radius of the fretboard. That means the fretboard is so much stiffer than it would be otherwise."

Ryan inspects paua abalone bridge pins after sanding.

Almost everything is built in-house, although other companies do most of the metal work. “Our truss rods are made from some guys that make parts for nuclear submarines," Ryan says. “It's high-tech welding and machining with alloys. We wouldn't know how to do that, but they are made exactly to our specs and our design." And that design is innovative. “In some ways, I feel it might be the single most important thing on my guitars. It makes the neck stable, allows you to dial in the perfect amount of fretboard relief, and it's going to remain where you left it in terms of release and action through the years. It's still very adjustable. It's two-way adjustable—I would call it micro-adjustable—because of the unique design."

A look inside a Ryan Guitar. All Ryan Guitars feature proprietary laser-cut bracing and acoustic honeycomb, engineered to keep the soundboard strong yet highly responsive to acoustic vibration.

Ryan is currently working on a series of 12 guitars to commemorate his 30th anniversary as a builder. His wood choice will reflect that as well. “The soundboard is going to be redwood," he says. “Partially because I love it. Acoustically, it's absolutely stellar. But also, it's a wood that was harvested here in California. So, it's keeping with the theme of 30 years in California building guitars."

The proprietary truss rods are one of the most important components on a Ryan guitar. They're made from high-tech alloys by welders who make parts for nuclear submarines. “I would call it micro-adjustable—because

of the unique design," Ryan says.

Over the years, Ryan's clients have included Laurence Juber (Wings), Jackson Browne, Pierre Bensusan, and many others. “Part of what's been so fun about this, especially in the early years when we came to the attention of many of the world's finest players, is that we're learning from them just like they're learning from us. In a way, it was uncharted waters. Guitars were being played in a new way, but weren't evolving. They were what they were from back in the 1920s and '30s. We like to feel we were the first company that said, 'Let's address that. Let's reimagine the guitar for the 20th century.' Now even that sounds dated, but we were always thinking, 'What's next? What can be done that's never been done before?' I gotta tell you, it's fun doing that."

Acoustic builder Kathy Wingert started building guitars because she couldn't find a comfortable guitar that wasn't

too boxy or big for her to play.

Wingert Guitars: Ergonomics and a Wide Wingspan

California builder Kathy Wingert makes a large assortment of instruments, including multiple steel-string models, parlor guitars, baritone guitars, and even a harp guitar. Her initial foray into building was to solve a simple problem. “I couldn't find a guitar that was specifically comfortable to my size," she says. “Smaller-body guitars tended to be boxy and big-sounding guitars tended to be too big to wrap my body around. Like many, including Martin, I tried a smaller-body guitar that was deeper, but that didn't do it, either. I started with a dreadnought and made it more accessible. That meant a long and mean waistline, plus, wherever your arm wraps over the guitar, it's quite comfortable."

Wingert mentored under violinmaker, violin family restoration artist, and upright bass expert Jon Peterson at the World of Strings in Long Beach before founding Kathy Wingert Guitars. “I didn't go out on my own until I reached critical mass," she says. “I had orders, the Healdsburg [California] show was coming, I'd worked around the clock for just way too much time—I mean, it felt like years. I just couldn't do it anymore. I put in notice and I had just enough money, just enough orders, and just enough of something going out the door that I was going to be able to make it to the show without my slow and steady repair check. I came home to find a cancellation notice from a client: 'Congratulations on your big step in your new career Kathy. I need my money back.'" She managed to launch her shop anyway and even returned the customer's deposit.

“The advice every young guitar maker gets coming in is: Get a lifetime's supply of wood on hand if you can," says Wingert.

Like many builders, Wingert is particular about storing and aging her wood. “I have the back and side woods in the garage where they are exposed to more weather changes and are less protected," she says. “I do that on purpose. If the wood is going to crack because of humidity changes, I want it to have already done it. I want to know that it's going to do that. My top woods are stored inside away from bugs, severe humidity changes, and also protected from UV. The advice every young guitar maker gets coming in is: Get a lifetime's supply of wood on hand if you can. I felt that was particularly important for the top woods so they could age and I could become familiar with their capabilities and their particular character. Each set of wood is different. Also, from tree to tree within a known species, there can be differences. There are differences in how they grow and where they grow. There are different parts of the tree—trees are many, many yards tall and we use a piece of top wood that is 20" of that tree. The tree takes twists and turns following the sun and there will always be some differences."

Kathy's daughter, Jimmi Wingert, does all of the guitar inlays by hand, with very little engraving and a focus on materials. This inlay by Jimmi was inspired by the work of Eyvind Earle.

In addition to 6-string guitars, Wingert builds one harp guitar a year. “I got dragged into the harp guitar world kicking and screaming by one of my clients," she says. “I pushed him away for over a year. He said, 'I wish I could talk you into building one for me.' And I said, 'Well, start talking.' I tried to push him away because it's such a different animal. I had no relationship with those instruments. We learned together. We went to visit Gregg Miner [of the Miner Museum of Vintage, Exotic & Just Plain Unusual Musical Instruments in Tarzana, California] and went through Gregg's massive collection of harp guitar instruments. An hour into it I knew my hesitance had been misplaced. I understood the instrument a lot better than I thought I would. It just boils down to: It's made of wood and it has strings on it. The thing with harp guitars is that they're under so much tension that there's not a lot of nuance to them. It's more important to get the balance of the body correct. Get braces put in places that make sense for the things it's going to do. And keep the structure as bulky as you can."

“I got dragged into the harp guitar world kicking and screaming by one of my clients," Wingert says. She usually makes

at least one harp guitar a year.

Wingert's daughter, Jimmi, does all the inlay work by hand. “Isn't she fabulous?" Wingert asks. “She chooses each piece of material for what she wants it to look like. She looks for orientation and figure: features of the materials themselves. She doesn't do a lot of engraving—that's not her thing—she gets it out of the materials."