Looking for a handmade acoustic guitar?

If so, you’re in luck, because the U.S. is crawling with builders. The Guild of American Luthiers claims more than 3,700 members and those members live everywhere. They’re in major cities, suburbs, and rural outposts—although many seem to congregate in areas like central California, the Pacific Northwest, and along the East Coast’s Acela Corridor [an area stretching from D.C. to Boston served by Amtrak’s commuter rail line].

But “congregate” is a relative term. Just because many builders live near each other, it doesn’t mean they socialize. Of the builders we spoke to for this roundup, most are happy to work alone at home and meet up with other builders at trade shows. That doesn’t make them loners, it’s just the nature of the work they do.

And a lot of people want to do that work, which in 2018, is easier to do than ever before. “There are too many builders and they are too good, right out of the gate,” legendary Sonoma-area builder Steve Klein says. “That’s partly because of the tools and materials that just weren’t available when I was building at the beginning. The ability of builders to make amazing things now is pretty amazing in itself. But I would still tell people to keep their day jobs if they’re interested in making guitars. Making a guitar is not all there is to making a living at making a guitar. You’ve got to sell it.”

Oregon builder Steve Kauffman agrees that there is an overabundance of new builders. Kauffman has worked with Klein for decades and now builds all of Klein’s acoustic models, in addition to his own line of guitars. “There are still a few excellent builders,” Kauffman says. “Where the market is saturated is with some of the second-tier builders—who build a lovely guitar. Many of them have graduated from one of the guitar-building schools and that has enabled them to enter the marketplace with a very professional-looking presentation.

But it takes experience and intuition to reach that top tier. I think where the market is saturated is with the appearance of top-level builders who still need to get their first 100 guitars under their belt before they really have their chops. It’s not that they’re not going to make it, it’s just that they’ve got to gain the experience and that’s probably a little bit more difficult to do.”

Guitar building, despite changes in technology and easier access to materials, is still a labor-intensive, time-consuming, detailed process. Most of the builders featured here are one-man operations with an output of 10-12 guitars a year. That doesn’t sound like much, but given that these instruments are handmade and complicated builds, one-guitar-a-month is the most a builder—especially one working without an apprentice or assistants—can handle.

But that modest output also makes good business sense. As Seattle builder Steve Andersen tells us, “I only have to sell 10 guitars a year and all I have to do is take care of myself. I don’t feel like I have to worry too much about being able to build enough guitars.”

That’s also true given the impact the 2008 financial crash had on the boutique guitar market. Orders didn’t come to a halt, although things slowed down. The market was flooded with used acoustics and, according to many builders, still hasn’t recovered. “That’s the first thing you’re going to sell if your kid is sick or you have to send them to college and you lost your job,” Santa Cruz builder Ed Claxton says about the drop in sales. “I think that is still affecting sales today.”

Despite those challenges—not to mention the headaches the Lacey Act and recent CITES regulations have added to the acquisition of exotic tonewoods—acoustic guitar building is in good shape.

But don’t take our word for it.

We spoke with five established old-timers and discussed the health of the current acoustic luthier scene. We also discussed the models they’re working on, their various innovations and contributions to the craft, their local building communities—including the lutherie guilds they may or may not belong to—and, most importantly, the stories and friendships they’ve acquired along the way.

Featured Builders:

- Hatcher Guitars | Peterborough, New Hampshire

- Klein & Kauffman Guitars | Sonoma, California and rural Oregon

- Ed Claxton Guitars | Santa Cruz, California

- Andersen Stringed Instruments | Seattle, Washington

“I’m not anti-science—I will certainly use that to inform me,” says luthier Mark Hatcher, “but the best guitars are made by artists. They’re not made by engineers.”

Hatcher Guitars | Peterborough, New Hampshire

New Hampshire builder Mark Hatcher relocated to the Granite State about five years ago from New Jersey. “New Hampshire is about the same size as New Jersey,” he says. “But it has eight million less people in it. That held a certain attraction.” One benefit was joining New England’s guitar-building community. “New Hampshire has the Guild of New Hampshire Woodworkers and included in that is the Granite State Luthiers Guild. I am the leader of that. There are about 56 builders in our guild. Our members range from people learning to build a guitar to people who have been doing it since the ’70s. This whole guild idea is a real New England thing and they didn’t have that in New Jersey. We have a lot less people here, but a lot more resources. It’s a big help and it’s great to be with your people.”

Hatcher calls this his lullaby guitar because he made it special for a dad in Seattle who wanted to sing lullabies to his preschool daughters. “I used my pillow headstock and it was my snuggest parlor guitar that he could sit with. I did moon and stars on the rosette and a little heart-shaped soundport. The whole thing was built around putting these kids to bed.”

Hatcher was a woodworker—his business was building strip-built sea kayaks—before he started making guitars. “It just occurred to me that maybe I should try a guitar,” he says about his initial inspiration. “I took two years making my first guitar out of the Cumpiano book [Guitarmaking: Tradition and Technology by William Cumpiano and Jonathan Natelson]. It didn’t come out great, but I was hooked.” His next steps were classes with Frank Finocchio, a former process engineer with Martin, and voicing lessons with West Coast builder Ervin Somogyi.

But the thing that put Hatcher on the map was photography. “In a previous life, I had run a camera shop,” he says. “I take better pictures than other builders do and that gave me a big leg up to get started. I posted build threads on Acoustic Guitar Forum and within a couple of months I had a two-year waiting list. That forum has really been the biggest part of my business. I’ve had other builders say, ‘You’re spending too much time with the camera. While I’m building guitars, you’re taking pictures.’ But I say that the camera to me is just another tool in the shop. Like every tool, you’ve got to master it. The camera is the one tool that keeps the other tools busy.”

This guitar, Penelope, is an Italian olivewood guitar from Mark Hatcher’s Unlimited Series. “Its design is inspired by Venetian architectural decoration,” he says.

Hatcher’s instruments take about four months to build. He starts a new one each month and averages about 12 guitars a year. He has five basic models, but those are just points of departure. “My philosophy of building is that I’m much more into the idea of a guitar as an art form, not an engineering form,” he says. “I’m not anti-science—I will certainly use that to inform me—but the best guitars are made by artists. They’re not made by engineers.”

This is a memorial guitar built on the theme of the poem “One for Sorrow.” It’s called the Magpie and features

“The Tree” mahogany.

That artistic aesthetic informs his guitars’ looks as well. “I spend a lot of time trying to tell a story with the guitar,” he says. “A recent guitar I made was for a fellow in Seattle. He has two preschool daughters and he wanted a guitar to sing lullabies to them. We made a lullaby guitar and the whole thing was built around that. I used my pillow headstock and it was my snuggest parlor guitar that he could sit with. I did moon and stars on the rosette and a little heart-shaped soundport. The whole thing was built around putting these kids to bed. When it was done, they sent me a picture of the whole family to show me how happy they were with their new guitar. To me, that’s great, that’s as good as it gets.”

Hatcher is currently working on his next Unlimited Series Greta model. “It’s inspired by a snail I met on the way into the shop one morning,” he says. “It’s a new design with a unique throated soundport system.”

Hatcher also takes an organic approach to design evolution, which explains his resistance to templates and CNC (computer numerical control). “I really try to do everything not just by hand, but also without jigs,” he says. “I find that once you make a jig or a CNC program, whatever it is you are making is now dead. It won’t evolve and it won’t change. But if you make them in your open hand, as years go by, without trying, they get better and better.”

Steve Kauffman (left) and Steve Klein (right) met at a Guild of American Luthiers convention in Boston in 1979. Kauffman moved to Oregon four years ago and took over Klein’s acoustic division. Klein still designs the guitars, and Kauffman builds them.

Klein & Kauffman Guitars | Sonoma, California and rural Oregon

Steve Klein built his first guitar in 1967. Early in his building career, Klein encountered design maverick Michael Kasha. “I met him through my grandfather, Joel Hildebrand, who was a well-known chemist at Berkeley,” he says. “I was invited to a party at my grandfather’s house and I met him while I was building my first acoustic guitar.”

In 2017, Klein & Kauffman finished their limited-edition run of seven 50th Anniversary Fibonacci model 7-strings.

“Michael Kasha was a physical chemist,” says Steve Kauffman, Klein’s business partner and fellow builder. “He understood a lot about physics and he was also an amateur guitarist. One day, he poked a mirror inside a guitar and he was shocked at what he saw. He wrote a lengthy paper—a very highbrow scientific paper with a lot of math describing how the guitar works—and the rights to that intellectual information was bought by Gibson. The bridge is the primary thing that drives the Kasha system, which focuses on the interrelationship between the bridge and the tone bracing on the top, as well as the concept of separating structural elements from tone-modulating elements.”

“You can see it in the asymmetrical bridge design, which is an impedance-matching system,” Klein adds. “That’s all stuff I got from him.”

Both Klein and Kauffman are self-taught luthiers, although Klein did do a brief, quasi-apprenticeship with classical builder Richard Schneider. (Schneider was known for his radical designs and 30-year collaboration with Kasha.) “I never had a formal apprenticeship with anybody,” Klein says. “Which is good and bad. It’s good in that I never got stuck in any of the silly traditions that people are tied into that don’t necessarily make a better guitar. They make a very specific guitar, but better is a relative term.”

Steve Klein works on the intricate inlays for the 50th Anniversary Fibonacci model, which is a collaborative design by him and partner Steve Kau man.

Klein and Kauffman met at a Guild of American Luthiers convention in Boston in the late ’70s, though at that point, Kauffman was already an established builder as well. “I made about 20 or 30 instruments before I met Steve Klein,” Kauffman says. “My big goal going in was to meet or exceed the quality of a Martin guitar. That turned out to be not as high a bar as I first thought. I wondered where to go from there and then I met Steve Klein. I realized that I had found someone who understood the physics of the instrument and understood how the components of the guitar interacted, which in those days, no one really understood. There was a lot of trade secrecy around brace carving and tap tuning and all of those mysterious mystical methods of getting guitars to sound good. He took a bit of a scientific approach, analyzed the components of the guitar, and set out to optimize all the different pieces.”

They’ve been collaborating since 1991. “Steve is a very creative, divergent guy, and he has a lot of other projects going,” Kauffman adds. “It seemed like a natural fit for me to start working with him. I gradually moved from constructing parts for his guitars, to doing some of the assembly, and then eventually I just took over building the guitars in my own shop. Four years ago, I moved to Oregon and took the whole Klein acoustic division with me.”

Built for Brooklyn guitarist Scott Stenten in 2001, this Klein & Kauffman DoubleGuitar has 17 strings.

Now all of Klein’s acoustic guitars are made by Kauffman in his shop in Cottage Grove, Oregon. Klein still designs the guitars and does inlays, but Klein’s primary focus these days is an ergonomic Telecaster—called the sTele—and Kauffman builds the acoustics. “He has taken it a step further in terms of refinement,” Klein says about Kauffman’s modifications to his designs. “He now builds a better Klein guitar than I ever did, without me really being involved at this point.”

Their building philosophy is system-centric, not wood-centric, or as Klein puts it, “If the system is right, any wood can be used. The different woods just produce a different color to the tone.” Kauffman adds that their initial bond was their interest in alternative tonewoods. “There really isn’t anything inherently magical about mahogany and rosewood and maple,” he says. “They just happen to be beautiful and available, but there are lots of other woods today that have both of those qualities, too, and make wonderful tonewoods.”

However, for fretboards, Kauffman still thinks ebony reigns supreme. “Ebony is far and away the best material there is,” he says. “Fully black ebony is becoming scarce and more expensive, but I also appreciate the character of the lighter streaks that come in the so-called ‘lesser quality’ ebony that we’re seeing today. I think people will accept it in the marketplace in time, and if they don’t like it, we can just dye it jet black. Easy enough to do.”

In the last few years, Klein Guitars officially changed its name to Klein & Kauffman Guitars, though don’t expect to see that on the headstock. “Stradivarius never inlaid his name in mother-of-pearl on the headstock,” Klein says. “So, no, I’ve never inlaid anything on the headstock.”

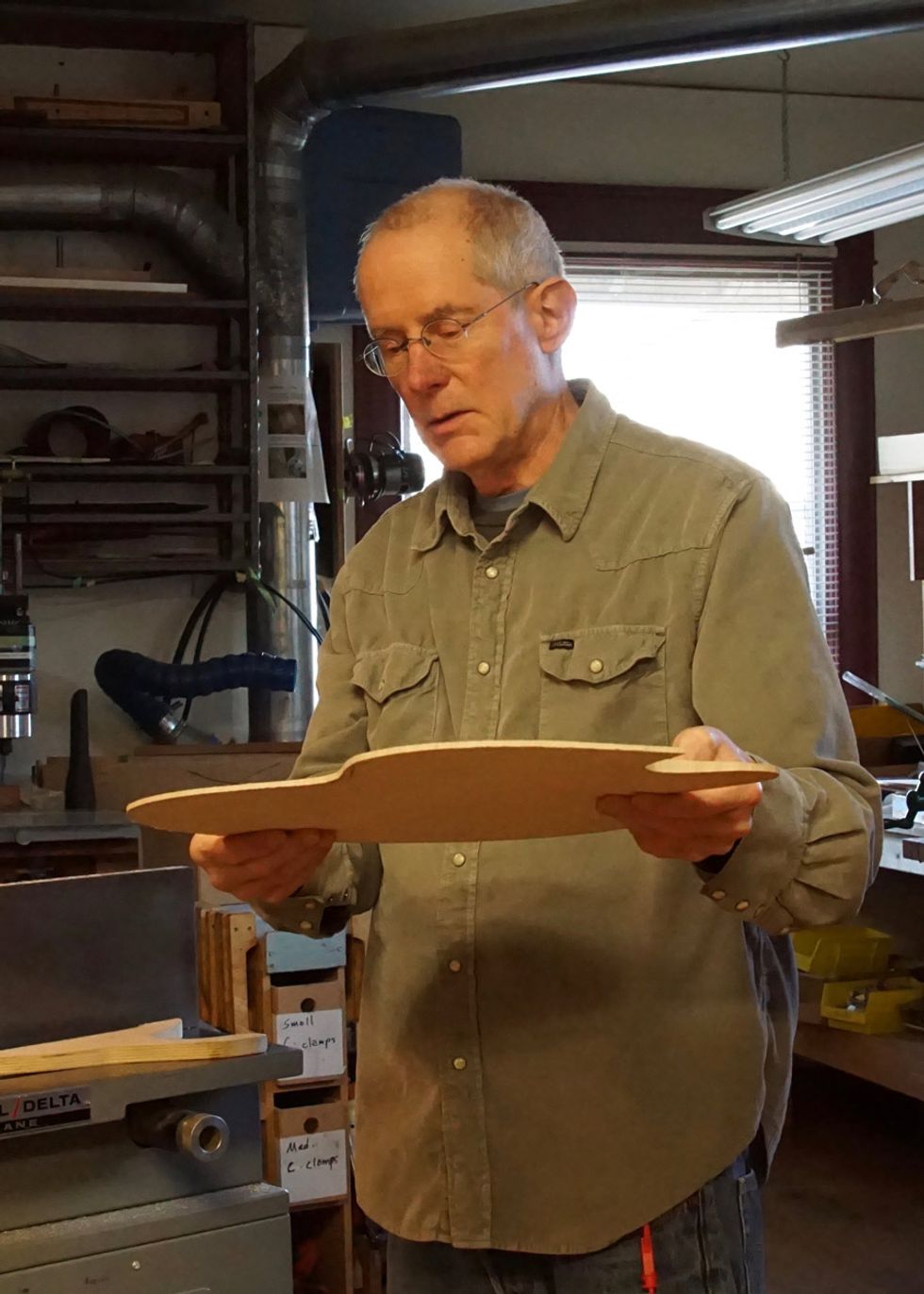

Luthier Ed Claxton in his Santa Cruz home, where the guitar-building magic happens. This photo appeared in the book, From These Woods: The Guitar Makers of Santa Cruz County by Jim MacKenzie and Renee Flower.

Ó2013 Renee Beville Flower

Ed Claxton Guitars | Santa Cruz, California

Now based in Santa Cruz, California, Ed Claxton started building guitars at the University of Texas in Austin. “I was going to the university and majoring in draft dodging, basically,” he says. “I met two philosophy majors who’d taken over a corner of UT’s arts and crafts center. They were making ouds and medieval instruments—things you’d see in Homer, in the Odyssey—weird lyres and stringed instruments made from horns, shells, goat skins. They took me under their wing and I worked with them for a period of about two years. I was playing guitar, so I decided to make a guitar. I got a Martin D-28, looked inside, and basically copied the Martin.”

Claxton worked the local music scene, which is a big deal in Austin, and sold his guitars to local musicians and people passing through. “I made a couple of guitars for Jimmy Buffett,” he says. “Eric Johnson had one. I made a guitar for Billy Gibbons and members of Jerry Jeff Walker’s band, Guy Clark, Americana guys. It was kind of easy for me to start out being a professional guitar maker because there was basically no competition at the time, as opposed to nowadays, where everybody in the world is a guitar maker.”

A parlor-sized guitar with fanned frets, the Composer is Claxton’s newest model. The back and sides are Brazilian rosewood and the top is Italian spruce from the Dolomite region. Claxton constructed the guitar’s case with Port Orford

cedar and ebony.

Claxton took a 10-year break from lutherie and built wooden boats and furniture in Maine before relocating to Santa Cruz about 25 years ago. “After a while, I got sick of the cold and we moved to Santa Cruz,” he says. “I put out my shingle again and started making guitars full time. At the time, Santa Cruz Guitars was around, and also some other handmakers and classical guys, but it wasn’t over-saturated like it is now. It was pretty easy. I networked. I went up to Gryphon Strings in Palo Alto, introduced myself, and they said, ‘We’ll sell some guitars.’ Word got around and it wasn’t that big a deal.”

According to Claxton, the scarcity and demand for tonewoods has dramatically increased their price. “When I started making guitars, my first few guitars were $300 or $400,” he says. “But back then, a set of Indian rosewood was about $15. A prime set of Brazilian from Michael Gurian was $60, and at the time, nobody was ordering Brazilian because they thought the price was too high.” That, combined with the 2008 financial crisis, has made the acoustic guitar market more challenging. “With the financial collapse a decade ago, there were like 10 million boutique guitars on the market for sale. I think that is still affecting guitar sales, because there are still a lot of used guitars on the market.”

Ed Claxton has a separate shop for storing and prepping wood, but he does all of the building out of his home with hand tools, rather than powered equipment. “I use planes and chisels, which is way more enjoyable,” he says.

Claxton constructs his instruments using hand tools. For a long time, he built about a dozen guitars a year, but he’s slowing his output to six. “About five years ago, we built a little studio for me to work in behind our house,” he says. “I have a 1,400 square-foot commercial space on the other side of town that I keep my machinery in. I build the guitars here at home, but I use my other place to prep wood, for thickness sanding, cutting out neck blanks, that stuff. I bring those parts home and I do 100 percent of the building here. Once I started working at home, I didn’t have immediate access to those tools, so I use hand tools a whole lot more. I use planes and chisels, which is way more enjoyable. Carving a neck with a CNC machine is not that much quicker. It still takes a while to do—you have to program the machine, which I could never figure out.”

This Ed Claxton Jumbo Model features Brazilian rosewood on its back and sides. “The wood is very old and was recycled from architectural timbers in Brazil,” Claxton says.

Claxton also doesn’t spend much time tuning tops. “When I bought wood—which I don’t buy anymore because I’ve got so much of it—the quality of wood that I bought over the years was so consistent in the characteristics, the weight and thickness, that I almost don’t have to do a lot between guitar and guitar. If you keep the quality of the tonewood in this little envelope—and if you build guitars like you always do—it’s almost guaranteed that you’re going to have a really nice-sounding guitar. I don’t use floppy tops. If you do, you have to do some serious modifications to the thicknessing, sometimes the bracing, but if all your woods have a similar high quality, then it’s guaranteed you’ll get a nice guitar.”

Seattle luthier Steve Andersen is currently working on his invention of a double-top archtop, which features a top built from two layers of spruce with a layer of Nomex—a lightweight, high-tech material—sandwiched in between.

Andersen Stringed Instruments | Seattle, Washington

Steve Andersen grew up in Phoenix, Arizona, and as a high-school student built his first guitar at what would eventually become the Roberto-Venn School of Luthiery. A few years later, he worked at the Franklin Guitar Company in Sandpoint, Idaho, and built OM-style flattops. But it wasn’t until moving to Washington state in 1986 that he discovered his passion: building archtops.

—Steve Andersen

“I moved to Seattle and started doing repair work,” Andersen says. “I met some players with really great archtop guitars—top of the heap, D’Angelico, D’Aquisto, Stromberg, Gibson—and there was nobody to work on them. I got really interested in that. A D’Aquisto would come across my doorstep—particularly his later stuff from the ’80s—and it was just so far out. You could see five of them and you could see how he was moving the bar. Every time he made a new guitar it was something new and different. I thought, ‘This really interests me. Why try to reproduce an instrument that was made 100 years ago—at the time I was making Gibson F-5-type mandolins—when I can build something where being unique and original is encouraged?’”

Andersen’s Electric Archie model resulted from a collaboration with Bill Frisell, who wanted a guitar he could travel and record with. The single pickup is a Lollar Imperial humbucker.

Andersen is serious about innovation. For example, he’s developed a double-top archtop, which features a top built from two layers of spruce with a layer of Nomex—a lightweight, high-tech material—sandwiched in between. “It derived from the classical guitar makers,” he says. “I thought, ‘Why hasn’t somebody tried this on an archtop?’ I played around for a couple of years, did a bunch of tests, showed it around, and got feedback on it. I made two, but I’ve put it on the back burner.”

This version of Steve Andersen’s Electric Archie has two Lollar Imperial pickups.

It’s on the back burner because his main focus is making a lighter, as in less heavy, archtop and—consistent with his innovative ethos—he does that using non-traditional materials. “To me it just makes sense,” he says. “If you want to make something really light, there is more than one way to do it. D’Angelico was from the old school of Freddie Green-type playing: You have to pound the guitar to be loud enough to fill up a room and be heard over the horns and other instruments. But D’Aquisto was making a guitar that people were playing as a solo instrument. It was much more responsive, which was a really cool thing, that you could make a guitar that has a lot more nuance to it.”

A headstock from one of Andersen’s custom one-off designs.

Andersen builds about 10 guitars a year, which is a good number for him, although he thinks the market is saturated, especially since the financial crisis a decade ago. “Things were pretty crazy up until about 2007 or 2008,” he says. “The financial crisis hit and I don’t feel it has picked up to where it was before. But I think that’s good. It was too frenetic for many years there. I would rather have 10 orders that I feel really good about and where the customer really wants the guitar. I don’t want to obligate myself to 25 guitars, and who knows if these guys are going to be around when the guitar is done?”

But don’t ask Andersen about Seattle’s local lutherie scene. Like many builders, he’s private, focused, and low key, which for the slow-paced world of lutherie, is an asset. “I’m not a particularly social person,” he says. “There are a number of hobby builders in this area. They get together and have meetings, but I don’t hang out with them. This is my job. I don’t want to leave my job and then go have a potluck and talk about guitar making. I have been thinking about guitar making all day.”