My interest in the science of sound stemmed from my inability to understand most modern luthiers’ theories or philosophies. One issue I’ve struggled with is why so many of the best examples of vintage guitars that are awesome on so many levels are now approaching 100 years old. Why doesn’t the same abundance of excellent sounding instruments exist in the modern era? Something was definitely spot-on with these older guitars. But when the tonewood stars are aligned, modern makers do occasionally come close to hitting that mark, so I don’t think it’s totally a question of those older instruments maturing through aging. I feel these guitars were good from the start.

So, what do I have to do to replicate the sound of those older guitars? And, most importantly, which sound is my primary goal? I’m sure I’ve said this before, but, just in case, I’ll say it again: The sound of world-class musical instruments is not subjective. They either fall into that category or they do not. However, there are still slight variables at play.

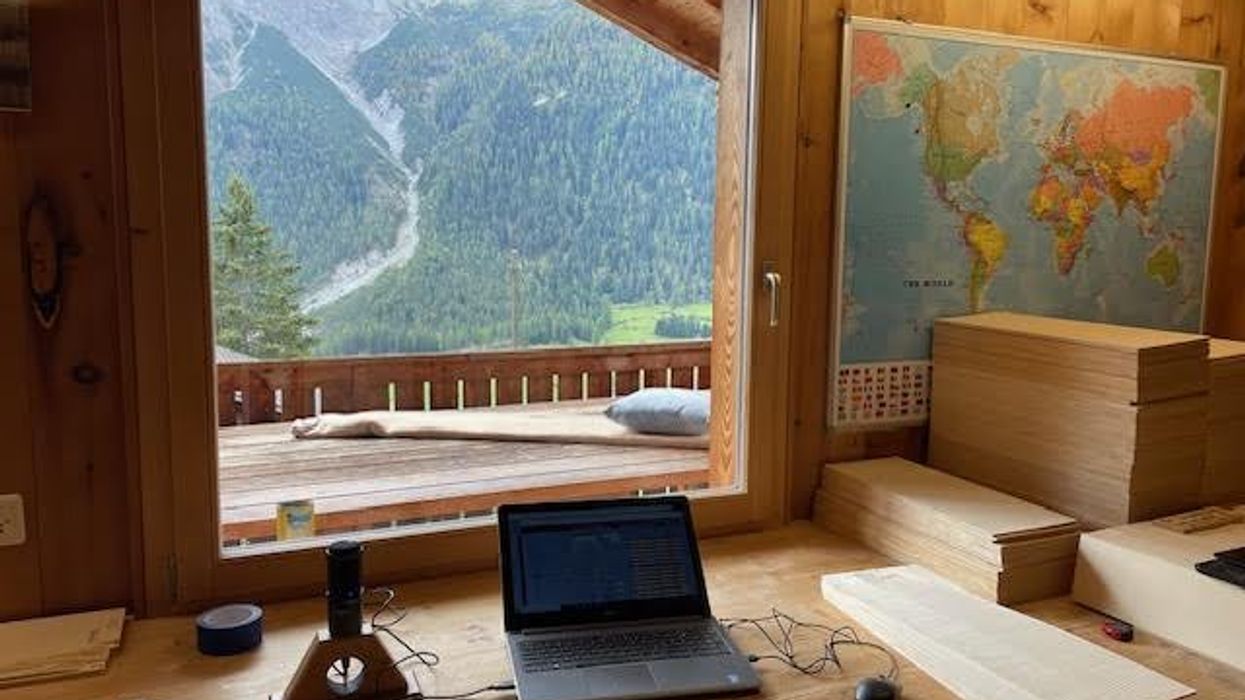

When I was developing my acoustic guitars, I had a blank canvas. All I had to do was make alterations until the instruments’ voice made me happy, and that became my sound. This method is called “form follows function,” because I altered the components until the instrument worked for me.

Reconstructing the sound of existing instruments is a more difficult task. In order to righteously pull it off, you have to replicate all of the components dimensionally, inside and out. Then, you can manipulate the tonewood to adjust the sound. This is “function follows form,” which is a much different, and ultimately more difficult, style of musical instrument making. In my shop, we call this style of backdoor guitar making “reverse profiling.”

Back in the day, I successfully pulled this off with vintage Gibson Advanced Jumbos and J-45s, but the Martin’s sound was more elusive. The added mass of the larger bracing and thicker tops can easily become lethargically dark and less responsive. But if correctly balanced, it’s a pretty special sound. Recently, I decided to move to the next level of reproducing the sound of vintage Martin guitars, specifically the late-’30s Martin D-18.

Unlike a modern sound that is commonly described as wet or lush, the vintage tone is clear and dry.

The first order of business was to locate an accurate example that had the desired sound and feel. There are varying sonic examples from any time period, so a marker was needed to keep the project on track and to compare for accuracy. This kept the project honest. I chose two models to compare: a 1937 D-18 with advanced bracing and wide string spacing, and a 1939 D-18 with non-advanced bracing and narrow string spacing. These were both iconic examples that had unique tones and folklore associated with their bracing patterns.

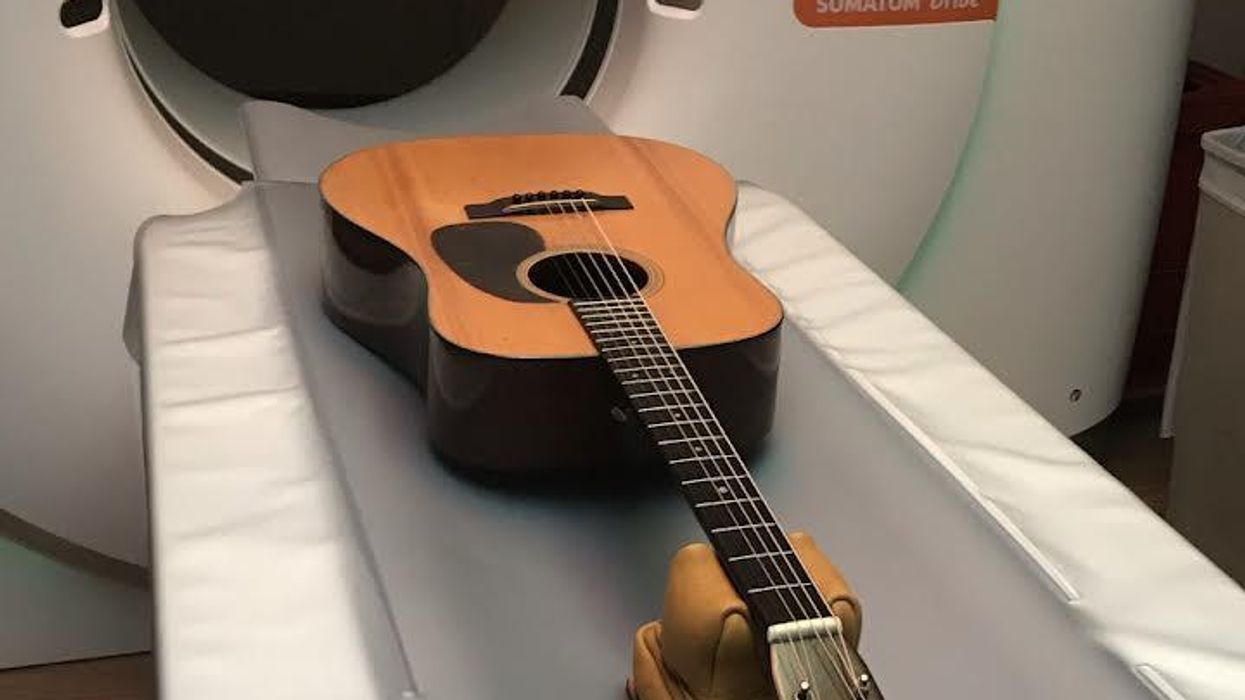

The next step was information gathering. Reverse profiling is trickier than a fresh build, and we need to understand the materials used a century ago. The data we compile plays a major role in the instrument’s tonal development and is absolutely necessary before we can develop any profiles. To achieve this, I worked with fellow luthier Tom Nania to CAT (Computed Axial Tomography) scan our vintage marker guitars. This way, we could calculate the density of the vintage tonewoods. Then, we physically mapped out the guitar’s weights and thicknesses inside and out. This generated the preliminary formula that was a key step in reverse engineering an existing guitar for reproduction. We established a definite path or, in other words, a recipe. When we make a change, which is inevitable, we will have accurate markers for each attempt.

I have always been impressed with the sound of vintage guitars. Unlike a modern sound that is commonly described as wet or lush, the vintage tone is clear and dry. If we can nail down this sound, we’ll gain a better understanding of tonewoods and their stability. This is only the beginning of a much bigger picture that will unfold over the next few years, and this 1937 D-18 is only one of the projects in the works. So far, our findings and progress are encouraging. I can’t wait to see where it ends up, but I expect good things.