Some fuzz players are so mired in pursuit of classic tones they forget that, above all, a fuzz should be able to scream like a banshee and stand out like a rabid, fanged rhino on jet roller skates. This forgotten knowledge—the loss of the essential fuzz spirit, some might say—has found us swimming in a Great Lakes’ worth of same-sounding fuzz riffs while a panoply of dirty, unique fuzz tones goes largely ignored.

The coolest thing about Crazy Tube Circuits’ Pin Up octave fuzz is how readily it sends you down those less-trodden paths. But the other best thing is that there are copious classic tones on tap, if you want them. The Pin Up does fuzz a lot of different ways. It’s not the most outlandish, radical, or deviant fuzz out there, but its ability to accommodate weirdoes and classicists equally—and so effortlessly—makes it a very powerful tool when you’re trying to quickly carve out a fuzz sound that’s not so run-of-the-mill.

Petite But Powerful Presence

Crazy Tube Circuits has fast garnered favor among some very dedicated and adventurous tone hounds. Players as varied as Bill Frisell, Brad Whitford, Nels Cline, and Lee Ranaldo use Crazy Tubes wares, and it doesn’t take too much time with the Pin Up to understand why—it sounds great, but the design is also very smart.

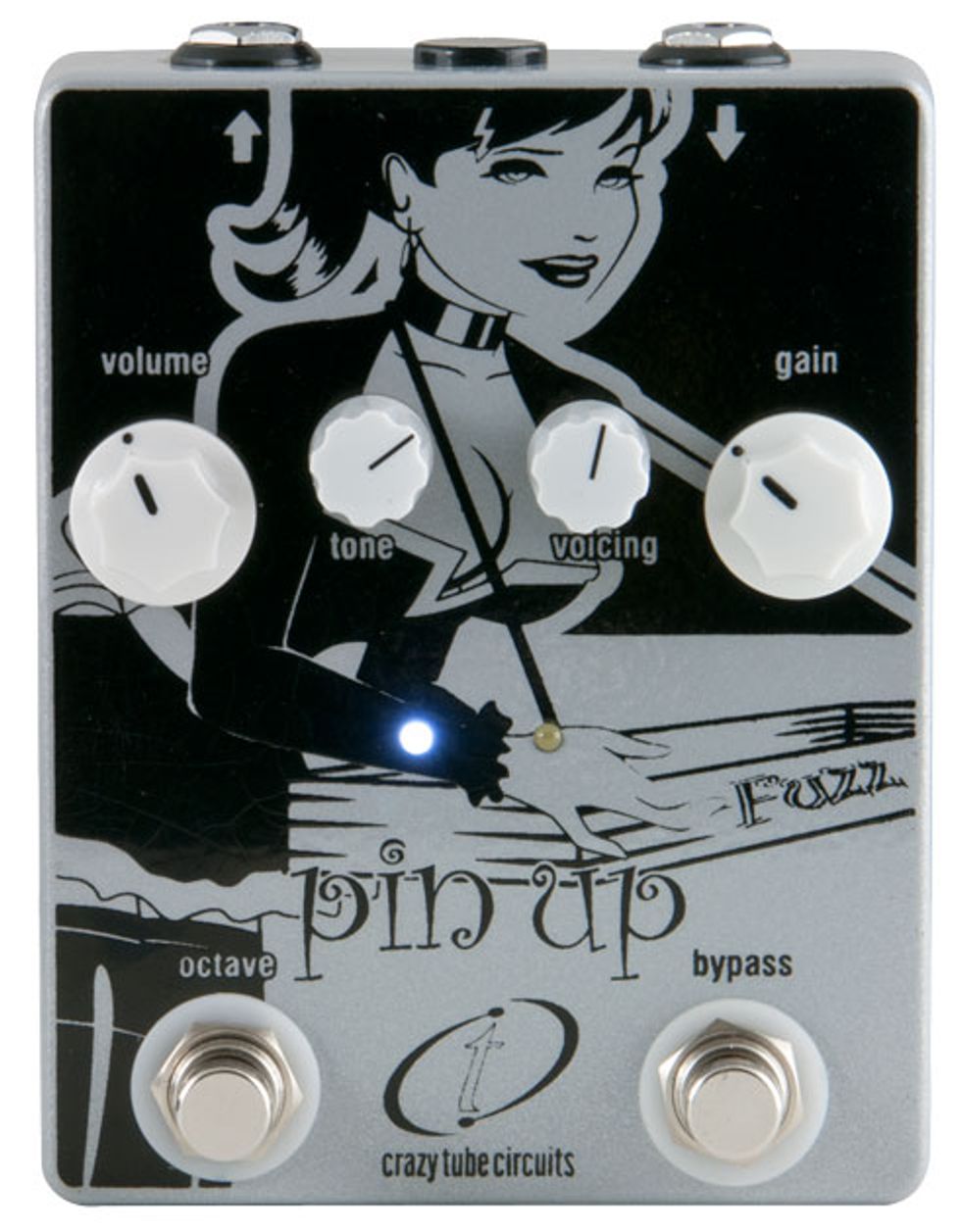

The Pin Up is compact for a two-switch fuzz. Some players might complain that the footswitches are too close together, but I never had a problem finding the switch I needed—even in a dimly lit rehearsal space with the Pin Up in a pretty busy pedalboard. In fact, I found the economy of size a real virtue and the interface intuitive. Any seasoned fuzz player can navigate the Pin Up with ease. The volume, gain, and tone controls all work the same way they would on a Big Muff or similar fuzz. Much of the Pin Up’s additional flexibility comes from a fourth voicing control that scoops or boosts the midrange. The icing on the cake, though, is the octave function—a bold-sounding octave-up function that expands the Pin Up’s vocabulary exponentially.

Sounds from a Looker

One real plus is how deftly the Pin Up stands in for distortion pedal along the lines of a Pro Co Rat, MXR Distortion+, or Boss DS-1. Set it up for unity gain, dial up relatively neutral tone, voice, and gain settings, and the Pin Up deals punchy, super-rich ’70s-style dirt. Adding volume and gain to taste adds ripsaw attitude to Johnny Ramone- and Steve Jones-style downstroke onslaughts and Grand Funk-like riffs.

With volume and gain wide open, the Pin Up has a tight, boxy, compressed fuzz character that rules for hot leads. Note definition is excellent, and yet it still retains that distortion-box-like articulation. The single-coils in my Jaguar and Stratocaster couldn’t quite coax the amount of volume you’d get from a higher-gain pedal, but the Pin Up was still tighter and more responsive to picking dynamics than something like a Big Muff.

The Pin Up’s voice and tone controls are huge assets if you tend to move between different pickups and guitars over the course of a set or session. Midrange boosts from the voice control add low-mid emphasis as well as a little presence, so cranking the voice control clockwise to its limits can make output more harmonically cramped, especially with chords. But it can also make a thin-sounding rig sound more massive, and it’s great for getting hazy, stoner-rock lead tones out of otherwise anemic-sounding instruments. If the lack of high-end definition gets you down, you can kick on the octave section, at which point the Pin Up spits out a rotund, snarky, almost cocked-wah-sounding lead tone that’s a pure shot of desert rock.

I tended to use the voice control’s scooped, counterclockwise settings with 6V6 amps, but those settings can also make a Twin or mid-watt, blackface-style circuit crackle with lively distortion. The voice control can just as easily tame the shrillness of a Stratocaster through a Marshall.

Ratings

Pros:

Seemingly infinite fuzz voices. Smart, economical design. At home with big or small amps.

Cons:

Somewhat pricey.

Tones:

Playability/Ease of Use:

Build/Design:

Value:

Street:

$269

Crazy Tube Circuits Pin Up

crazytubescircuits.com.com

The tone control has an wide, useful range, too. Ease back on the volume while opening up the gain and tone, and the Pin Up spits out a menacing, ’67-style psych/biker fuzz. Throwing the octave on top generates a paint-peeling fuzz that will cut through anything while remaining notably resistant to feedback—a great asset in a recording session. Less trebly settings are great for fattening-up lead tones and filling harmonic space in an overdub. They tend to cloud the output of mid-scooped single-coils, but a hot humbucker generates burly, cutting lead tones and greasy, grinding power chords. In general, humbuckers are very much at home with this fuzz.

The octave-up function is basically smooth and tuneful. It’s also highly reactive to tone and voice knob adjustments. The octave can be very hairy—especially with a big amp—but between the extra control you get via the tone and voice knobs and the basic singing quality of the octave voice, the Pin Up is pretty easy to tame. With mids boosted, a neck-position single-coil yields one of the snorkliest, most focused and playable octave tones around. And while the Pin Up isn’t quite as thrillingly chaotic as a SuperFuzz, its more reserved voice works better for chords than any other octave fuzz I can recall—it can impart an almost horn-section-like set of overtones to power chords.

Home-recording fans who work with smaller amps and lower volumes are bound to treasure the Pin-Up’s civilized and brutish capabilities. It’s a dastardly little monster with a Blues Jr. or Champ—readily dispensing filthy ’60s garage-trash buzz and grinding chord tones. Interestingly, the voice and tone controls feel especially reactive and versatile when cranked through a small amp, making it easy to dial in a perfect (or perfectly nasty) fuzz tone before you ever hit tape or your digital interface. The octave function ups the insanity just as readily with small amps, too.

The Verdict

You can make a lot of fuzz racket with the Crazy Tube Circuits Pin Up—from barbaric and skanky to more familiar classic-rock sounds. The combination of a clever, powerful EQ and a separate octave footswitch make it a fuzz of many very colorful personalities. And if your pedalboard is bogged down by a fuzz surplus, the Pin Up can very capably replace a fuzz or two and a distortion pedal. That versatility makes the fairly steep price tag look a lot less painful. It also makes the Pin Up a pedal any fuzz-inclined touring or session guitarist must investigate.