Machine heads, tuners, tuning keys, gears, or pegs: Whatever you call them, these devices determine how easily your guitar gets in tune and stays there. It’s worth investing in high-quality tuners, but do some homework before you upgrade.

A good set of tuning keys can make an enormous difference in how well your guitar performs. Many guitars come from the factory with inexpensive tuning keys, so it’s usually a good idea to upgrade them. But before you open your wallet, be sure you choose the correct keys for your guitar. Trying to install keys that don’t fit properly can devalue your instrument and cause mechanical problems. Fortunately, you’ll be able to avoid these issues with a little knowledge.

Some background. Guitarists and luthiers use various names for tuning keys, including machine heads, tuning gears, tuning pegs, and of course, tuners. In the early days of the guitar’s evolution, there was little choice when it came to replacing your keys. Only a few companies made “geared keys.” Before that, most lutes and guitars used friction pegs, like those found on a violin. These pegs were generally made from hardwoods and were very difficult to use.

Boasting art-deco knobs and cast housings, these sealed Grover Imperial tuners

are often found on archtop jazz guitars.

One of the first known manufacturers of a geared tuning key was John Frederick Hintz, who developed his device in 1766. It was revolutionary at the time, but became obsolete by the 1800s when John Preston developed a superior design. Most antique keys had a very low turning ratio and were poorly geared. The result was tuners that would slip out of tune, making life difficult for performers.

Fast forward to the present, where we have dozens of choices. Gotoh, Sperzel, Waverly, Grover, Planet Waves, Kluson, and Schaller are among the manufacturers of high-quality tuners, and these companies offer models that retrofit most guitars and provide superior gearing.

Decoding a tuner’s ratio. When describing their tuners, manufacturers include a ratio in the specs. This two-digit number tells you how many times you have to turn the tuning key’s button for the string post to make one full revolution. The lower the gear ratio, the fewer times you have to turn the button for the post to make a revolution. Conversely, the higher the ratio, the more times you have to turn the button for the post to revolve completely.

A relatively recent arrival to today’s tuner scene, Waverly keys have rekindled interest in the old-school, open-gear design. They may look like ancient, inexpensive keys—the kind once used on budget or student guitars—but they’re precision machines.

Using a flathead screwdriver to remove vintage-style mounting screws.

Because a higher gear ratio lets the post rotate in smaller increments, you have more control over the tuning process. In other words, an 18:1 ratio offers a finer degree of control than an 11:1 ratio. Lower ratio keys make it harder to reach a precise string tension, and this can cause you to jump past the desired note as you tune up.

Modern replacement keys have a much higher gear ratio than vintage keys. For example, modern Grovers have ratios from 14:1 to 18:1. New Klusons are as high as 19:1. Gotohs range from 14:1 to 28:1, and Graph Tech’s new Ratio sets have variable ratios, from 39:1 on the low E to 12:1 on the high E.

Look beyond the ratio. If you’re planning to upgrade your tuners, there’s more to consider than just the gear ratio.

For starters, if you have a vintage guitar (or an expensive modern instrument) and the keys are deteriorating or not working properly, I recommend installing direct replacement keys that do not require any modifications. Whenever you drill new holes or enlarge the existing holes in the headstock—or anywhere, for that matter—it devalues the instrument.

For a vintage axe, always store the original keys in a safe place to preserve them. Gotoh, Kluson, and Grover make excellent direct replacement keys that typically offer higher ratios than vintage tuners, but are otherwise a drop-in retrofit for Strats, Teles, Les Pauls, and other popular models. If you do the research and find the right tuner, you can make a clean installation with simple hand tools. We’ll cover this in a moment.

If you have a modern instrument and decide to install tuners that aren’t direct replacements, be aware that this usually affects the guitar’s tone. When you change mass on the headstock—by adding heavier or lighter hardware—it changes how the neck responds to string vibration. It’s hard to predict exactly how the tone will change—and guitarists debate this endlessly—but if you like how your guitar currently sounds, think twice before you install non-direct replacement tuners.

Locking keys. If your guitar has a vibrato arm or tremolo bridge, locking tuners can really help you keep in tune. Locking tuners clamp the string in place either by using a rod inside the post or a collar that wraps around the post. Both methods are effective and eliminate the need to wind the string around the post more than once. When you eliminate multiple windings, the string doesn’t have to reseat itself on the post when it returns to pitch after being slackened. Companies that make direct locking replacements for existing keys include Planet Waves, Schaller, Sperzel, and Gotoh.

Staggered-height posts. If you have a flat headstock with six tuners in a single row—like those on a Fender—think about upgrading to tuners that have staggered-height posts. On most guitars, staggered-height tuners eliminate the need for string trees, and this too can improve tuning stability—especially on guitars with whammy bars. Staggered tuners typically have posts in three sizes: strings 1 and 2 take the shortest posts, strings 3 and 4 take the medium ones, and strings 5 and 6 use the tallest.

If the staggered height tuners aren’t direct replacements for your existing tuners, remember that changing the mass on your headstock has sonic consequences. You might actually like this, but you can’t really predict the outcome in advance.

Changing your keys. If you select direct replacements for your existing keys, installing the new ones is a simple process. Typically, you need a small screwdriver (flathead or Phillips) and sometimes a 10 mm nut driver or a deep-well socket.

Most modern keys use Phillips-head screws.

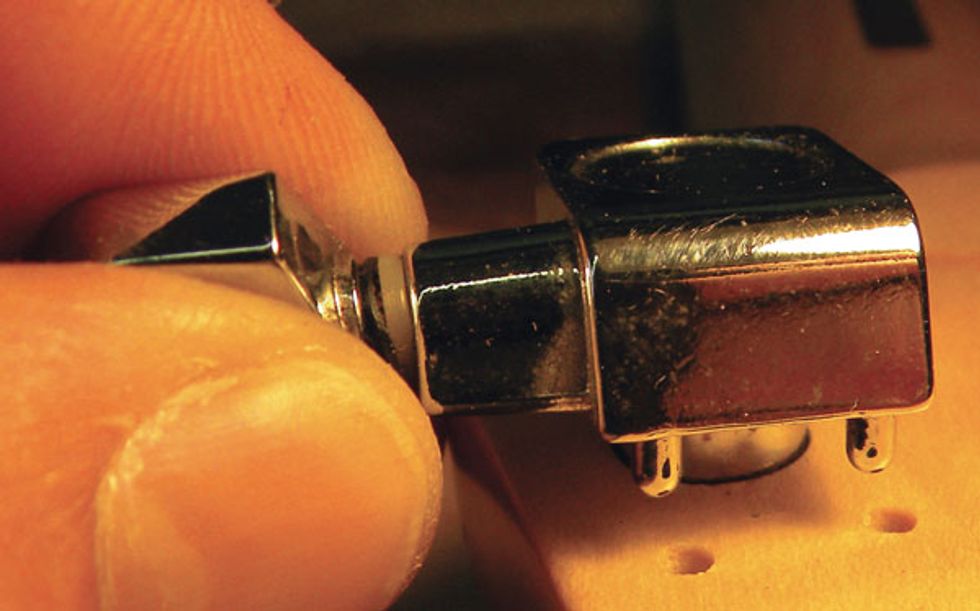

Removing a key’s threaded collar using a 10 mm nut driver.

With the strings removed, unscrew the mounting screws on the back of the headstock, then (if applicable) remove the threaded collar that surrounds the post with a 10 mm nut-driver. If your guitar has press-in bushings, I recommend leaving them in. Removing the bushings can damage the finish or wood surrounding the post hole.

When installing the new keys, insert the key into the hole, install the screw on the back of the headstock, and then finally tighten the threaded collar. Do not use an open wrench or adjustable wrench on the collar. The wrench can slip and butcher the nut or put a big ding in your headstock. A nut driver or deep-well socket lets you apply gentle downward pressure as you tighten the threads and this keeps the tool in place.

Don’t attempt to tighten a threaded collar or bushing with an adjustable crescent wrench—it can slip and mar the collar or headstock.

Caution! Be careful when tightening the screws and the collar. If you over-tighten the screws, you’ll strip the headstock wood. This damage can be repaired, but it requires gluing dowels into the headstock. If you over-tighten the collar, it will strip the threads and ruin the collar. Damage to the collar is irreversible, and you’ll have to buy another tuner.

Screwless keys. One more thing: Some tuning keys don’t attach to the headstock with screws. Instead, they have one or two alignment pins on the underside of the shell that insert into the back of the headstock. Check this carefully when you replace your keys and make sure you buy the correct style to fit your guitar.

Some tuners have one or two alignment pins instead of screws. Carefully check your guitar before buying replacement tuners to assure a correct match.