|

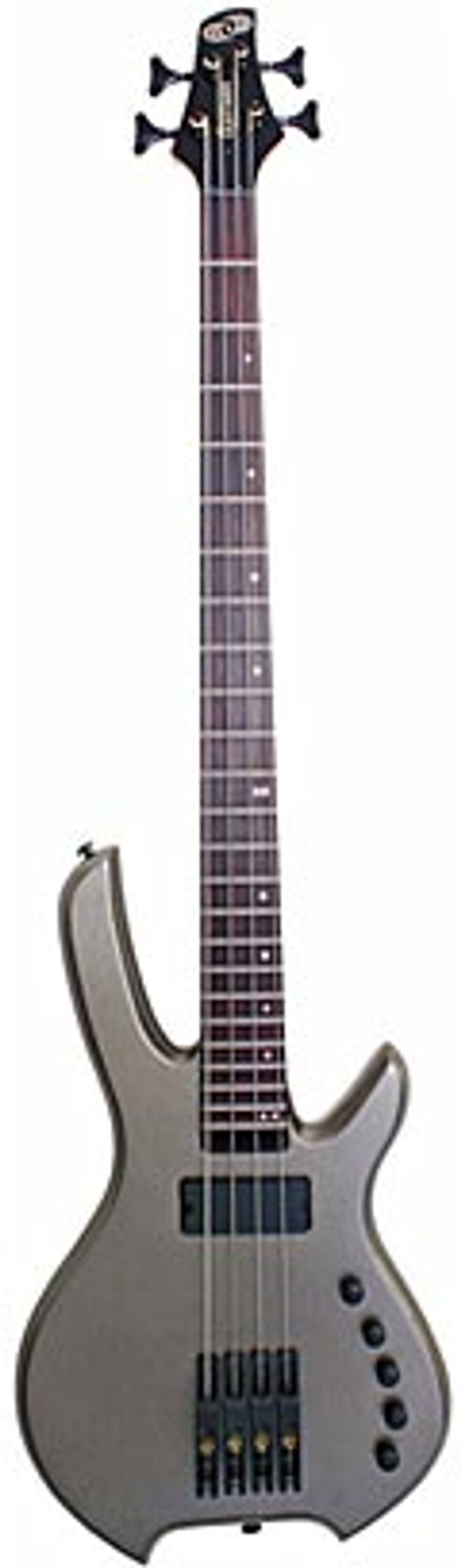

Enter Chris Willcox and the small crew behind LightWave Systems. With the help of infrared technology, LightWave Systems have brought the pickup kicking and screaming into the 21st century. With several bass and guitar models, Chris has dispensed with age-old magnetic principles in favor of new technologies that promise to make players think carefully about how they interact with their instruments and what exactly they should expect from them. And while they may not sound like magnetic pickups, that’s exactly the point.

We spent some time with Chris discussing LightWave’s newest products, what players can expect from these pickups and the challenges of introducing new technologies into a market smitten with the past.

| |

|

I did an apprenticeship in New Jersey when I was 17, learning how to build guitars with John Vile, who was a Master Craftsman from C.F. Martin. He was an expert in pearl inlay and did all of the inlay work on the D-45s and the top-ofthe- line Martin models. Then he went off on his own to start his own custom shop and hired me on as his assistant. He built the guitars and I did a lot of the operations. I also learned how to do repairs, and that partnership lasted until I moved to California in 1976.

How old were you when you headed to the West Coast?

21 years old. I had played in bands back East, but I was never that serious about becoming a musician – I preferred working on the instruments. But I moved to California and by the early eighties I had gotten settled and started up a little guitar shop. It was a part-time gig; I still had regular day jobs. Towards the end of the decade I initially got the idea to build some primitive prototypes of optical pickups, and I quickly realized I was onto something, so I started applying for U.S. and international patents in the early nineties.

| |

|

We started out providing only the electronics. We were providing systems for mostly boutique and custom builders, and we were focused on product development. We did that for a few years, and a little over two years ago I started designing complete instruments. As we speak, I’m currently working on developing a new division of LightWave Systems called LightWave Guitars, which will be dedicated to the instrument side of the business – it’s still an exclusive and proprietary system for us.

What initially drew you to the idea of optical pickups – did it begin with an interest in traditional pickups?

Well, just like your magazine’s tagline, I was experimenting in the never-ending search for tone and sustain, mostly with electric guitars. I began with the usual ideas, trying various wood combinations, building techniques, bolt-on necks versus through the body designs and so on. What I found was that the voice of the instrument was so dependant on the type of magnetic pickups on it that I began to wonder if there was some other way to sense string vibration that was non-intrusive and not so heavily voiced as magnetic pickups are.

Of course, I like magnetic pickups to this day – I have great respect for them – but I thought there might be something different out there. At the time, infrared technology was beginning to proliferate. A lot of it began in military applications and was really expensive, but it started to trickle down into consumer goods – these days it’s everywhere and quite affordable. I got interested in the fact that you could look at a string and the string didn’t realize it was being sensed.

Did you envision the optical pickup as a response to a perceived need within the industry, or was it more of an attempt to push the bounds of existing pickup technologies?

I perceived it as a desire rather than a need. I’ve always believed that players want alternative tones and experiences from their guitars and I got such a positive response from the early prototypes that I just couldn’t help but launch it into fullscale product development. I went on to believe that this is an important contribution to the continued evolution of guitar technology.

It could actually become an industry standard for some segments – for example, it could be identified as a need in terms of electrifying acoustic instruments. Piezo pickups are well entrenched in that segment, but they have a lot of drawbacks. People have accepted them for what they are but we offer some serious advantages in that area.

In electric string instruments, we definitely want to emphasize our differences as an alternative. We’re not saying, “We’re gonna replace magnetic pickups,” we just want to be another option in the mix. You know how guitar players are as collectors. We’re not saying you’re gonna get rid of all of your guitars, just that you’ll want one of these too.

How does the infrared technology actually “look” at the string, as you’ve described it, and how does that make it to the amplifier?

Each string has its own array of infrared emitters and photodetectors; the emitters cast a shadow of the string onto the detectors. When you vibrate the strings, the size and shape of the shadow changes, which in turn modulates a standing current in the detectors. That signal, just like most transducer signals, is very small, so it goes immediately into a motherboard, which is in a cavity at the back of the guitar, and contains preamps. The motherboard amplifies the signal and also has a socket for a daughterboard, which is where all of the tone controls happen. From there it goes directly to your standard 1/4” jack and cable. It’s a completely analog system, and the overall sound is clean, balanced and natural.

It might sound like rocket science, but we’re not doing anything exotic. For what it does, it’s a very robust and dependable system, and it really isn’t that complicated. This system is compatible with all preamps, amplifiers and signal processors in the marketplace, and it provides you with a kind of high-definition string signal to start with, so any amplification and signal processing you plan on doing is noticeably enhanced.

| |

|

All analog, all of the way. There’s no digitizing anywhere.

The words “transparent response” are all over your marketing materials. Can you describe the tone that these pickups generate in comparison to a traditional magnetic pickup?

Well, let me start with magnetic pickups since you’ve made the comparison. All magnetic pickups have built-in voicing – they cannot be flat by nature. Even the flattest model adds 6 dB of gain per octave across the entire spectrum, so they are really changing a lot of what the string is actually doing. You can think about it this way: there is nothing richer than the sound of the vibrating string itself. Any means of transducing it is going to be a subset of that. Magnetic pickups also dampen sustain and make sustain and decay sound somewhat unnatural, especially towards the end. They alter the actual harmonic structure of string vibration, choking some of the harmonics – Stratitis would be an extreme example.

Optical pickups have no inherent coloration, so if you set all of the controls flat you’re really getting the sound of the string, the instrument and whatever the player is doing. You get a really rich, fullbandwidth signal with extended frequency response; really long, natural sustain; and a nice, even decay. It’s kind of like a grand piano and the nice, natural decay you get when you hit a note. You’re really starting with a truer and more accurate string signal source, and that’s just the direct clean sound of the pickup. You’re free to add EQ without fighting existing curves. You get a lot of versatility and your downstream effects will be enhanced because you have a better signal at the front-end. Another thing you will notice as soon as you plug in is that the system is dead quiet and doesn’t generate any of the annoying hum and buzz associated with magnetic pickups. Recording engineers love it.

So the wood and components still play a critical factor in the instrument’s tone with the LightWave System?

Absolutely, and perhaps even more so, because you’ve taken the pickup out as a primary voicing generator.

Does this transparency help create an honest instrument?

I think that’s a really good word. A lot of players also tell us that it improves their technique. The sensitivity provides a more honest playing experience. Also, fretless bass players seek out the most realistic upright bass sound they can get, and they are really attracted to our fretless models.

What are the tradeoffs for these benefits?

The obvious one would be that you pay a slightly higher price, especially in the early stages of development, just as you do with any new technology. We have lower volume production, so we haven’t achieved economies of scale. Magnetic and piezo sensors have been around for a long time – they’ve become commodities with a very low cost of entry.

What about powering the system? Could that be seen as a drawback?

It is a rechargeable nickel-metal hydride battery system. Some people – before they learn how it works – consider it a drawback, but this actually functions like any other active pickup system. By now most people are familiar with recharging batteries in pieces of equipment, and once they learn how simple and reliable it is consider it more convenient than 9V battery systems. There’s no more running to the store for a battery or finding your replacement battery is also dead.

It’s a rapid recharge system and takes about one hour to charge, giving you 16 hours of playing time. The battery and charger are very reasonably priced, so buying spares and replacements isn’t hard on your wallet, and the batteries have many charge cycles, so it’s a very easy technology to get used to.

As far as power running out mid-set, there’s a battery status LED right on the bridge that begins to dim, giving you better than a two-hour early warning. And the instrument never just dies – it fades out over that two-hour period. If need be, you can play and charge at the same time, with the charger plugged in.

Who is the target audience for your technology?

There’s no narrow focus here – we’re going after all string instrument players and all styles of music. There are advantages here and certainly the majority of players are looking for something to differentiate themselves. We’re also aiming at anyone who wants to capture a natural acoustic string sound at any volume for live performance or recording. Players will come to find that they’re more intimately connected to the strings and the instrument when they’re getting this level of sensitivity from our transducer.

It seems that your efforts to date have centered on the bass guitar. What’s the reasoning for that?

Bass was a good starting point, mostly from the standpoint that they’re bigger strings and are spaced wider apart. Bass players are fairly open to new technology, and they were very impressed with the extended frequency response here. It really shows up on 5-string basses; the low B has never sounded this tight and focused. All of those things came together and bass was just our first product.

| |

|

Actually, that was mostly requested by players, and to be honest, I resisted at first due to the fact that if you put the magnetic pickup on there – even if you’re not listening to it – it’s still doing string damping stuff. But a lot of our boutique builders began building instruments with both, and I became rather enamored with the combination. There’s also a novel set of tones you can get by mixing the optical and magnetic pickups with the pan pot. Some players also wanted the convenience of having both systems on one instrument. We listened to our customers and found there was enough demand for it.

The bridge designs on your basses are quite striking. Who did you work with to develop them, and do they provide any benefits over a more traditional design?

The bridge was originally a LightWave design; we call it the “monolithic bridge.” We did work closely with Graph Tech to develop the actual product and they helped us create it out of a proprietary blend of Graph Tech materials, which offers sonic benefits as well as being very rugged and dependable.

Design-wise, I was looking for what you might call a mechatronic approach, where each one of the monoliths integrates everything. It contains the mechanical termination of the string, the electronic and transducer functions, and action and intonation adjustments all in one assembly. It looks cool, too.

We wanted to draw some attention to the fact that the guitars look different from the standpoint that you don’t see any magnetic pickups, which gives our instruments a real clean look. But then it draws your eye down to the bridge and the fact that you’ve really got something different going on.

You’ve also been promoting your new Atlantis ElectroAcoustic guitar – could you tell us a bit about that?

The Atlantis will be shipping within a few weeks – the first production run is underway. We were able to transfer the technology to the full range of string gauges. Wire strings were a challenge, but we’ve found a way to work with them and now the system can be adapted to any instrument we choose. We certainly plan on many guitar variations.

Why were wire strings such a challenge for your system?

Well, they’re just so small that the shadow I was telling you about actually gets lost when we used the bass transducer assembly. So everything has been miniaturized and fit into a much tighter spacing. But we’ve solved that problem – we can pretty much sense any string gauge that’s out there now.

As you know, guitarists are notoriously traditional. Has it been difficult to get guitar players on board with the design of the Atlantis ElectroAcoustic?

It certainly plays a part – vintageitis is what you’re talking about and it certainly has an effect. But we’ve really focused on getting guitars into the hands of players, in terms of expanding our dealer network, because you can write about it and advertise and do reviews, but until a player actually gets it in their hands, they won’t understand that it’s a new tool, a new means for expression. Granted, there are players who are not going to be early adopters, but there’s a large segment of players that are interested, and I think that’s an advantage in many ways. Magnetic pickups have been around since 1935 and the primary guitar designs on the market are from designs created in the fifties. The last real development in pickups happened in the eighties when they went active. So obviously there’s room for something new and different. Look around – every other segment of this industry has experienced technological evolution in the last 20 years that you can barely keep track of, so why not the pickups?

The ElectroAcoustic has a unique blend of radical and familiar aesthetics – are you looking to come out with a more traditional approach for those players suffering from “vintageitis?”

With my guitars, I try to give them a modern, recognizable design, but nothing that’s too out there. I try to create them based on the tradition that I learned how to build guitars in. I carefully choose the woods and don’t use any radical materials – the proper woods for tone generation don’t change. It’s just that with the optical pickup you get more tone generation from the instrument, the choice of string and the player’s style and technique.

| |

|

It can have a much greater importance. The pickup is very sensitive to different string materials and types because there’s no more interaction between the pickup and the string. You don’t need a ferrous string anymore – you can use any type of string you’d like, composition-wise. Eventually we plan to come out with some custom string options once the instrument base is larger. For instance, a copper-wound string would give you a piano sound, which you could not do with a magnetic pickup. There’s certainly a lot of uncharted territory here. Players who buy our instruments typically put their favorite brand of strings on there to start, but they’ll often find that they can experiment a lot more.

You currently market your own instrument designs, something you don’t see from most pickup manufacturers. Did that arise out of a desire to create an entirely integrated solution or out of sheer necessity?

It’s actually more interesting for me as an integrated solution. I’m very quality and detail-oriented and like having control over the instrument design. The pickup system is not a retrofit at this stage, so even when we worked with boutique and custom builders, they had to learn how to integrate the system into their instruments. I also believe that a complete instrument helps us to build our brand identity – it’s not a LightWave pickup on some other guitar. We offer an integrated system where the instrument and pickup are designed together for maximum performance. It puts the company in control of the growth and development of the entire technology.

Are there any plans to work with manufacturers in an OEM capacity?

Long-term, yes – there are a lot of manufacturers that are interested, but it’s too early to name names. We went through an OEM phase early in the beginning, working mostly with boutique and custom builders, and that was a great experience for us, in terms of product development and working with some great builders – Joe Zon, Harry Fleishman, Jens Ritter, Michael Spalt, really too many to name. LightWave pickups ended up on a lot of fantastic guitars out there and I think eventually we’ll get back to it on a bigger scale where we’re working with large, global companies. It’s one step at a time; we definitely felt that doing our own instrument lines was the logical next step.

With the nation’s economy seemingly headed for a soft patch – if not a full on recession – has it affected your plans? Do you expect players to scale back?

We’re not planning on it – you know how musicians are. The electric guitar industry has been resistant to economic fluctuations over the years and we certainly didn’t position ourselves to become a huge company overnight. We’re just trying to go after a reasonable share of the market so that we can continue to grow and offer the technology to more players on more stringed instruments.

How many people are involved with the company now?

We’re keeping it lean. This facility [in Carpinteria, CA] is mostly design and final assembly. To keep the price reasonable, we farm out a lot of the manufacturing – PC boards, guitar necks and bodies and a lot of the sub-assembly. So it’s less than ten people here right now but that’s certainly going to change. We do intend to do all of the final assembly here and the proprietary transducer work is always done in-house.

Are you relying on overseas manufacturing?

Just for the necks and bodies. We assemble, setup, test and QC every instrument here with the highest standards. We manufactured in the U.S. for a while but the price was so high that it was really a great point of resistance in getting this into a player’s hands. Now we’ve got a great manufacturing partner with really high quality and reasonable pricing. Our basic models go out the door for under $1000, which was a dramatic change for us. When we were doing production completely in the U.S., our instruments were in the $2000-$3000 price range and that kept it out of a lot of players’ hands.

What’s in store for the future of LightWave Systems?

Many electric stringed instruments. We’ll make a version of the Atlantis guitar with nylon strings, a solidbody electric guitar and maybe an archtop. We’ll definitely get into bowed string instruments – violins and cellos – since magnetic pickups don’t work with them and piezos have their shortcomings. We also envision add-on pickups for acoustic instruments. Thinking long-term, probably even a system for grand piano, which would be pricey but in a live concert or recording situation would be a great transducer solution.

We’re also very excited about hex effects (trademarked as HexFX), which is our implementation of MIDI and Hex technologies. The motherboard has a second socket and if you plug in another daughterboard, it can route the individual string signals to a 13-pin connector. From there the signal is compatible with pretty much any MIDI equipment, the Roland V line and any variety of synth boxes, as well as fan-out boxes for individual string signal routing. And when I say individual string outputs, there is a totally separate transducer for each string with zero electrical crosstalk. That gives us some real, noticeable differences like chords that are never muddy – they’re very clear and well articulated. Even when playing tight intervals like minor seconds and double-stops you can clearly hear each note. So that’s another exciting opportunity for us. Ultimately, we aim to be the dominant force in an entirely new segment of the guitar industry.

LightWave Systems

lightwave-systems.com

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)