The Danelectro Nichols 1966, in spite of its simplicity, feels and sounds like a stompbox people will use in about a million different ways. Its creator, Steve Ridinger, who built the first version as an industrious Angeleno teen in 1966, modestly calls the China-made Nichols 1966 a cross between a fuzz and a distortion. And, at many settings, it is most certainly that.

But it can also be fuzzier than you expect. And calling it a distortion sells short its fine overdrive and boost qualities, as well as its responsiveness to guitar volume and tone variations, and picking dynamics. It interacts with amps spanning the Fender- and English-sound templates as though it has a very individual relationship with each. It rarely sounds generic. And its tone range makes it a potential problem-solver in backline situations or studio sessions where you’re looking for something predictable or altogether weird—which is reassuring if, like me, looking at 10 different gain devices gives you a nervous sense of decision fatigue. The Nichols 1966 may not always be precisely the gain unit you’re looking for, but can also produce scads of tones you may not have known you needed.

Exponential Possibilities, Many Personalities

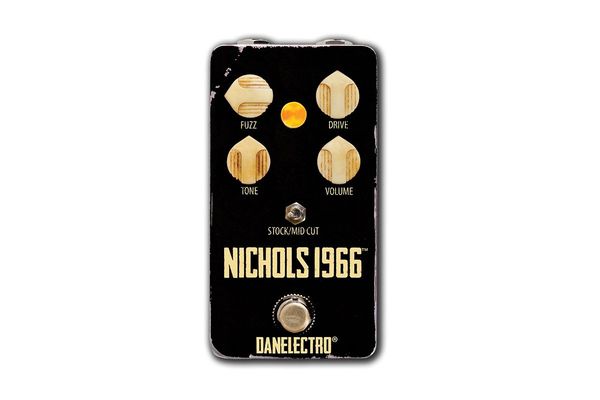

When the knob count on a pedal goes up, that doesn’t always make the device more effective or complex-sounding. But when controls work as interactively as they do on the Nichols 1966, four knobs and a mid-cut switch can make for a very broad palette, indeed. You don’t often see fuzz and drive controls together on a pedal. Usually, the two terms are interchangeable. Here though, the fuzz and drive knobs have a very different effect on the Nichols 1966 output. They also react very differently to single-coils, humbuckers, and American- and British-style amps.

At its maximum, the drive control’s distortion can sound and feel comparatively midrange-y, not too saturated, and sometimes brittle—requiring careful attention from the tone control. In general, advanced drive settings (with low fuzz) favor slightly attenuated and bassier tone-control positions and the stock EQ toggle setting. At their best, these combinations evoke small vintage amps cranked to their nastiest or larger amps with more sag. Advanced drive control settings with toppier tone settings and/or a mid-cut EQ setting are much less flattering, particularly with single-coils and/or high-mid-focused, British-voiced amps. Introduce humbuckers though—especially neck PAFs with less aggressive tone profiles—and you can coax muscular, hazy gain with tough tenor-saxophone tonalities, which are fatty and delectable. The drive control can also help shape great clean-boost sounds and treble booster-stye distortion. There are discoveries aplenty you can make with the right guitar-and-amp recipe.

The fuzz control is the hotter of the two, in terms of gain. At maximum levels, it’s scorching and buzzy, and, if you like really burning fuzz, it’s actually quite forgiving of trebly settings and mid-gain scoops, even with single-coils. A great technique for creating nasty, mid-’60s fuzz colors is to set the fuzz tone to maximum, scoop the mids, add a fair bit of treble, and add drive to taste.

“It’s plenty loud, and with the volume, fuzz, and drive all the way up, it’s positively brutish.”

Danelectro may allude to the Nichols 1966 being something less than a full-on fuzz, but I just spent the weekend listening to Davie Allan and the Arrows Cycle-Delic Sounds, and if this isn’t fuzz—as in getting-jumped-by-a-gang-of-leather-clad-mace-wielding-wasps kind of fuzz—then I’m Tony Bennett. There may be fuzzes that are silkier, smoother, or sound more like classic fuzz X or guitar-hero Z. But if you regard fuzz as an attitude more than a sonic commandment etched in granite, you’ll be tickled by how unique the Nichols 1966 sounds in that capacity. It’s plenty loud, and with the volume fuzz and drive all the way up, it’s positively brutish.

But it’s the playful use of the interrelationship between fuzz, drive, and tone together that showcase the Nichols 1966’s real strengths. Used actively, intentionally, and with an attentive ear, you can fashion high-gain distortion and fuzz sounds as well as varied, unique overdrive colors that you can fit to single-coils or humbuckers and that summon unique textures from each. The pedal responds effectively to guitar tone and volume attenuation without sacrificing much in the way of dynamic sensitivity. And, at less trebly and cutting settings, it still works as a vehicle for funky David Hidalgo/Tchad Blake Latin Playboys fuzz or Stacy Sutherland’s 13th Floor Elevators drive sounds that are distinctive in a mix in spite of their low-midrange emphasis.

Fuzzy Finish

Though generally sturdy, the Nichols 1966 isn’t a flawlessly executed pedal. The three circuit boards—one for the I/O jacks and DC 9-volt jack, another for the footswitch and LED, and a third for the drive and tone circuitry—are affixed to the enclosure independently of each other, which conceivably makes the pedal less susceptible to cataclysmic failure and more conducive to repair. On the other hand, some of the finishing work around some solders looks less than pretty and irregular. I’m not sure this affects pedal longevity. I’ve seen decades-old fuzzes with solders light-years uglier than these that work perfectly. At $199, you do like to see slightly tidier finishing work. Then again, I suspect most of what looks sloppy here is only superficial. The pots and switches all feel sturdy and smooth.

The Verdict

If you’re non-dogmatic about how much your fuzz, overdrive, or distortion sound like a certain template—and if you have the time and presence of mind to tinker with the Nichols 1966’s interactive controls to learn how they work with each other and different guitar and amp pairings—you’ll find the Nichols 1966 a pedal of power, great utility, copious surprises, nuance, and happy weirdness.