With all the hype surrounding new technologies today—with digital this, sampled that, modeled tone signatures, and profiled sounds—it’s nice to find an establishment like Invisible Sound Studios in Baltimore, Maryland, a place where musicians thrive on getting sounds the old-school way—from a nice guitar and a great amp. After all, that’s how most of the classic recordings were made.

Invisible Sound was founded by Dave Nachodsky and Joe Rinaolo, two guys who happen to own an absolute treasure trove of cool old amps. So many that part of the building has come to be known as the North American Guitar Amp Museum. It’s a working museum for musicians who want to lay down tracks with a mindboggling collection of amps you just don’t see everyday—such as a mid-’60s Selmer, a 1966 Ampeg Portaflex SB-12, a 1960 Magnatone Troubadour, a JMI-built Domino/Vox AC4, and a ravaged KT88-driven Marshall Major.

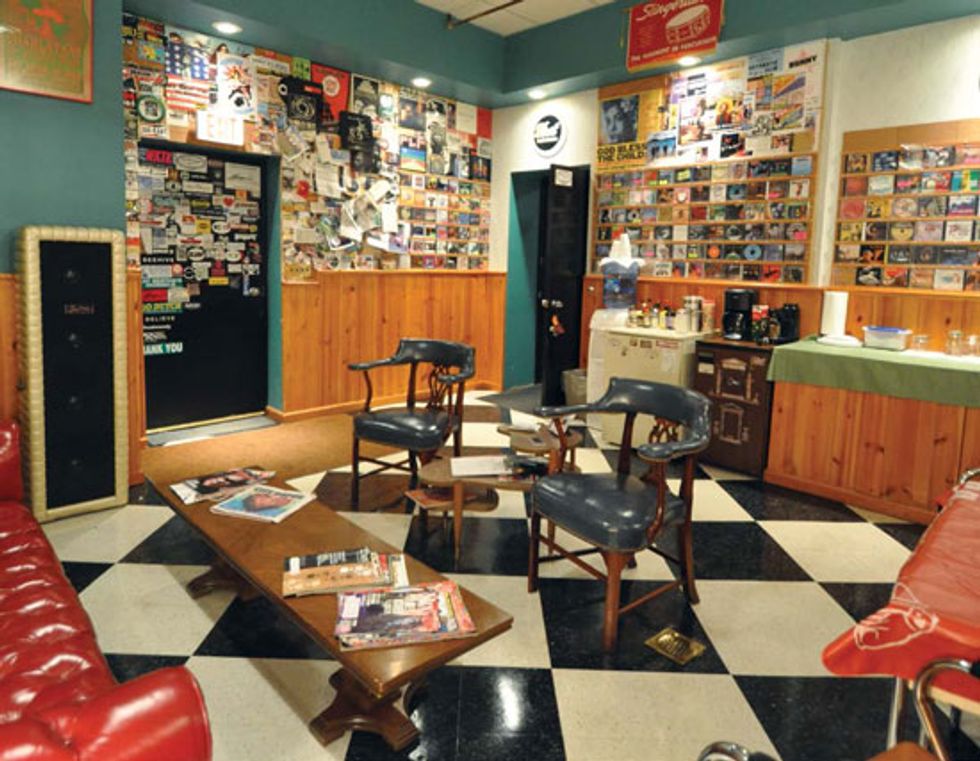

With its vintage posters and CDs, checkerboard floor, ‘50s endtable, plush couch, and a tuck-and-roll Kustom cab with four speakers in a vertical array,

Invisible Sound’s lounge exudes a hip yet homey vibe perfect for chilling between takes in the equally vintage-vibed tracking rooms. Photo by Tina Nachodsky

Nachodsky and Rinaolo’s amp collection has grown considerably over the years. The heads, cabs, and combos now line the walls of at least two large studio rooms, and in most places they’re two rows deep, if not more. Most every piece is readily available to add tone, drive, and color to the recording experience. In addition to the necessary recording gear—including a remarkable collection of vintage microphones—the amp collection sits amongst piles of vintage drums, stompboxes, and processing gear, including a couple of very cool plate reverbs! We asked Jeff Bober—who co-founded Budda Amplification and now runs East Amplification, in addition to writing our monthly Ask Amp Man column—to sit down with Invisible Sound’s Nachodsky and Rinaolo to discuss the collection, explain how it got started, and describe some of their favorite amps.

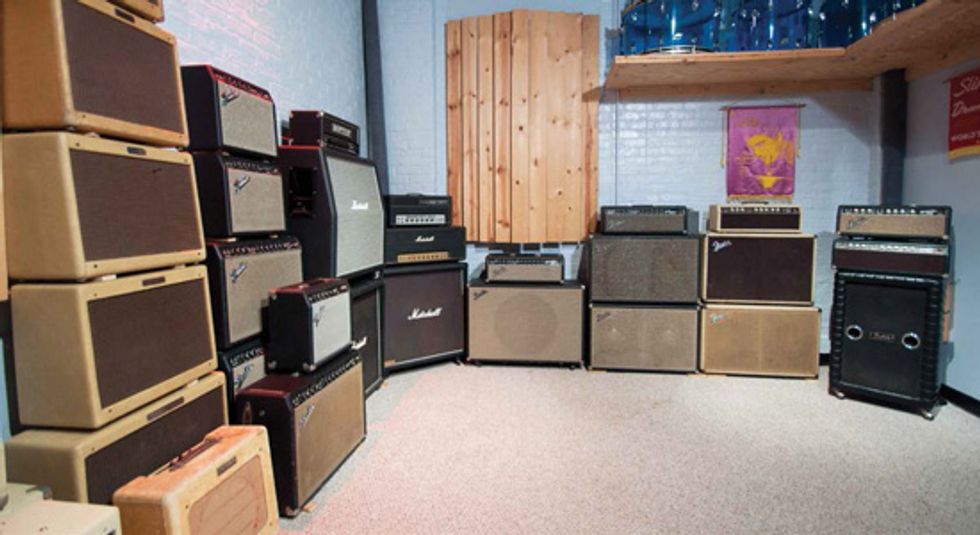

The “Wailing Wall” at Invisible Sound/North American Guitar Amplifier Museum has just about every flavor of American and Brit grit (and grind)—from

blackface and silverface Fenders to specimens from Ampeg, Sunn, Traynor, Vox, WEM, Tone King, East Amplification, 65 Amps, Budda, Marshall, Selmer,

Hiwatt, Mesa/Boogie, JMI, and Orange. Photo by Tina Nachodsky

How did you guys get into the recording

and amp-collecting business in the

first place?

Dave Nachodsky: I started out playing

bass in bands way back in the ’70s and

early ’80s. I kind of fell into recording

accidentally—started recording our own

stuff, playing with Joe. Then we started

recording friends’ bands and other bands.

After a year or two had gone by and we

hadn’t recorded any of our own stuff, I

realized, “This is a recording studio,” and

it went from there.

Joe Rinaolo: The studio was actually in the basement of my house. Dave’s brother’s band wanted to record, and they offered us $15 an hour, so we started with that. From there, we started collecting amps. Brett Wilson and the True Tones came in, and they were using vintage amps, so I got the bug there. He got me my first tweed Fender Champ. Guitars were already hitting their market value and amps were just starting to creep up, so we ended up getting quite a few. The rest is history.

So when was this—when did you start

collecting amps?

Nachodsky: The ’80s. As a bass player, I

had an Ampeg SVT and a half SVT [4x10]

cabinet, another smaller Ampeg head, and

a Music Man head, and Joe had a [Fender]

Twin, a Marshall, and a couple of other

amps in the basement room where we put

the drum kit—and where we separated

the laundry! It was a small room, and we

had our amps along one of the walls. One

day someone said, “Nice collection,” and

it was, like, “Oh yeah, I guess so!” People

would see that and come to a second session,

and they would bring something and

say, “This was down in the basement or in

a closet.” The tweed Deluxe was that way.

There was no tweed on it and someone

had shellacked it—right, Joe?

Rinaolo: That was the Vibrolux. It was in his closet and he traded a drum machine for it.

Nachodsky: It hummed and had no tweed, and it probably had a bad speaker. He was, like, “Will you guys give us an hour of studio time for this amp?” So we said sure. At the time, it was 15 or 20 bucks an hour. We got that amp fixed and added it to the lineup along the wall in the little basement.

Rinaolo: We used to do our Saturday trips to Chuck Levin’s Washington Music Center shop, and at the time they had another store, what was that other guitar store?

Nachodsky: American Guitar Center.

Rinaolo: There were all these guitar stores within the same vicinity, so we’d go down and get some Chinese food and hit all these stores. Amps at the time were reasonably priced, so we would jump on quite a bit. I got an old Ampeg V4 with a cabinet for three and a half hours of studio time. At that time, I went to Precision Audio Tailoring to get my amps serviced.

Nachodsky: And you [Jeff] were fixing them all.

Rinaolo: Working out of your house—that’s where we met.

Pining for a plexi? Invisible Sound and the North

American Guitar Amplifier Museum have plenty

to jumper, including both 50- and 100-watt 1972

Marshall JMP Super Leads (above, sitting atop a

Marshall slant 4x12 with Celestion Greenbacks),

or a 1965 Marshall JTM 45 Mk II driving a 1970

Marshall 8x10 (below). If you’re looking for a different brand of British

brawn, they’ve also got 1976 and 1974 Hiwatt

DR-103 heads that you can pummel the mics

with via a 1975 Hiwatt SE 4123 4x12 cabinet, or

a 1965 Vox AC-50/4 Mk III driving a 1973 Orange

4x12 cabinet (above right). Need pulverizing

American metal tones? No prob—plug into the

Mesa/Boogie Dual Rectifier Solo head and route

it through the Marshall Bass Lead 1960 straight

4x12 with Greenbacks (above right). Photo by Tina Nachodsky

The “Wall o’ Heads” features a 1963 Gibson

GA-5 1x6 combo, a 1968 SOC head (a rebranded

silverface Fender Bassman), a 1966 Fender Bassman, a

1966 Fender Bassman “kickback” 2x12, a 1963 Fender

Bassman, 1968 Fender Bassman, 1972 Ampeg B-25,

1970 Sunn 1200S, 1973 Traynor Custom Special – YBA3, 1976 Ampeg SVT,1970 Ampeg SVT. Then begins

the Wailing Wall, with its 1968 WEM Control ER-15, Vox

AC15H1TV, 2006 Tone King Meteor 40 Series II, East

Studio 2 (serial no. 001), 1964 Fender Twin Reverb with

original JBL D120s, 2000 Budda Super Drive 45 series

II, 2000 Budda Super Drive 30, Budda 2x10/2x12 cab,

and 65 Amps London. Photo by Tina Nachodsky

Yeah, it seems that’s where everything

starts—in somebody’s house

or basement. So it sounds like the

studio and the amp collection started

simultaneously?

Nachodsky: Yes. And when we moved

here in ’90, this place was so much bigger

[than the old location]. We thought we

were going to take all our stuff and fill this

space, but it filled like that much [holds

hands close together]. Then it became like

every hoarder’s dream—“We have to fill

this space!” So we did. [Laughs.]

Rinaolo: It was a labor of love—“If you build it, they will come.” At the time—before eBay and before everyone knew everything about vintage stuff—these were just “used” amps. The guitar market had taken off, but the amps had not gone through the roof yet. We were finding them at little stores like Gordon Miller Music and Links Music in Pennsylvania. Anywhere you went, they had used amps—and they were pretty well priced, like $250 to $450.

Nachodsky: They were cheaper than that—at Petros you had to turn sideways!

Rinaolo: Petros was a whole other story.

Nachodsky: They were all tube amps, and they were like 50 bucks for a run-of-the-mill Fender Bandmaster. They’d have four or five of ’em. The Twins were $150 at one point.

Rinaolo: You could walk into someone’s house and they’d say, “My grandfather had an old amp,” and you could pick it up for a couple bucks. I mean, nobody knew what anything was at the time. But now with eBay, everything is “vintage.”

Nachodsky: A lot of guitar players went contemporary in the ’80s and ’90s and into the 2000s—a lot of guys were not playing tube amps, or if they were, not old tube amps. A lot of people had a rack processor with a stereo power amp so the chorus could go out to two stereo cabinets.

The east wall features bass and echo gear,

including ’60s Premier 90 and Danelectro 9100 reverb

boxes, a ’61 Watkins/Guild Copicat tape loop, a ’60s

Cordovox 1x10, ’60s and ’70s Echoplexes, a ’73 Roland

RE-201 Space Echo,’60s and ’70s Ampegs—a Gemini I

and II, V-4s, SVTs, Portaflex fliptops (B-18-N, B-15, and

SB-12), a Reverberocket, and a J-12 Jet—a ’69 Gretsch

Twin Reverb, a ’59 Magnatone 213 Troubadour, a ’70s

Kustom 100, a ’72 Plush P-1000S, ’70s Sunn Concert

Lead and Concert Bass heads, and ’70s Acoustics—a

450 head, a 301 1x18 cab, and a 134 combo. Photo by Tina Nachodsky

That was ubiquitous in the ’80s—the

refrigerator-sized rack and stereo cabinets.

Nachodsky: I remember when you could

buy a Marshall head for 200 bucks a piece,

every day of the week—as many as you wanted—because the older guys who had all that

stuff thought they had to do the new thing.

I think there was a bias against tube amps—they were not in vogue. At guitar shows back

then, sometimes a guy would bring an old

tube amp, a tweed or something small, and

set it under the table in case someone wanted

to hear a guitar. We’d go and say, “Want to

sell that amp?” and they’d say “I guess. What

will you give me for it?” They were focused

on the guitars. At the time, a 1950 Fender

Telecaster or Broadcaster guitar was worth

what, five grand? And even then, people were

asking “When will the insanity stop?” Yet the

amp that would have been part of the same

vintage rig wasn’t worth $200.

It was just an afterthought at that point.

Nachodsky: Yes. But the amps caught up pretty quickly over time.

Rinaolo: Back then nobody seemed to realize the amp was the other half of it.

How many amps do you have in your

collection now?

Rinaolo: About 175.

Nachodsky: The last official count was about 160, but we’ve added since then.

Rinaolo: We added the new East [Amplification] Studio 2—so we’re at 176! [Laughs.]

Whether you feel the need for

tweed or like your Fullerton tones

in brown-, black-, or silverface

varieties, Invisible Sound’s back

room is stocked with all the Fender

flavors you could ask for—from

Champs and Deluxes to Twins,

Tremoluxes, Bassmans, and Band

Masters. And then there’s the

cabs with everything from 12"

JBLs to 15" behemoths. If you’re

looking for something nastier,

there’s always the Sovtek, Sound

City, and Marshall plexi heads

and the straight- and angled-front

Celestion-loaded cabs. Photo by Tina Nachodsky

And they’re all available to use in your

studio. When you’re recording, does it

make your job easier having access to all

of those classic amps?

Nachodsky: That’s a double-edged question,

because it depends on the player—their experience, their guitars and equipment,

and what they’re used to working

with. I wouldn’t say it makes it easier, but

it always makes the result better. And the

other thing is, we’re not snobs. If a guy

comes in and says, “I usually use this cheap,

solid-state practice amp and I’ve built my

sound around it,” I say “Bring it in—we

don’t have that, and we could spend six

hours trying to make some other amp

sound like what you have.” I may have

my opinion on the sound and/or the gear

they’re using, but what matters is that we’re

ready to go and they’re comfortable.

Rinaolo: But for the right person—a player who’s a little bit more into his sound—it’s great having a crayon box of colors at your fingertips. Sometimes you play a song and you get out there to play the lead and it doesn’t fit with a Marshall plexi, but when you plug the same guitar into a Vox AC15 it just sits right in the mix. Having that palette to choose from really makes a difference—not to mention the different drums and microphones we have. That gives us the ability to go in a lot of different directions. We also do re-amping, so if you want to send in a clean track, we can re-amp to any one of the amps and send the new track back to you.

Vintage mics galore! Invisible Sound’s microphone collection includes several shelves full of old and new

models from Neumann, AKG, Shure, Sennheiser, Sony, Electro-Voice, and Oktava, as well as this shelf full of

enough chrome-grilled vintage RCAs to please Elvis, Harry Connick Jr., David Letterman, and Casey Kasem. Photo by Tina Nachodsky

Though outfitted with a modern hard-disk recording setup and a 64-input Amek console, Invisible Sound’s control room is outfitted with plenty of vintage

processors, including a Universal Audio 565 filter, a Roland SRE-555 Chorus Echo, MXR Pitch Transposers, Altec limiters and tube mixers/preamps, Spectra

Sonics Complimiters, and racks from Lexicon, Yamaha, Roland, dbx, Joemeek, and Avalon. Photo by Tina Nachodsky

Of all the amps, what are your personal

favorites?

Rinaolo: My ’62 offset Marshall is probably

my favorite. It’s a remake of the first hand-wired

JTM45 that Jim Marshall made.

Nachodsky: I like the specialty things, like the Gibson GA20. It’s sort of Gibson’s version of a Deluxe. I bought the second one because the first one was a ridiculous screamer—people don’t expect it to do what it does. We have two of those. The second one is just okay, though. For a long time, you couldn’t give Gibson amps away. Even now, they’re definitely not priced or valued like Fenders. Although the GA40 is a big one right now. I like the smaller stuff and the weird stuff, like the Magnatone Troubadour with the tremolo, or the Cordovox—which has a 10" guitar speaker and no horn, but it rotates. A Leslie has a horn and a 15" speaker, so it’s kind of the opposite of a guitar amp and it has its own sound. But you drive the Cordovox with another amp, and man, the brown Deluxe through that is ridiculous.

Rinaolo: It’s kind of hard to pick your favorite child. They all have a story about how we came by them—and that’s a whole other thing.

Nachodsky: There’s a particular one that I feel is possessed and I’m afraid to change the tubes in it—the 50-watt Super Lead JMP Marshall. There are certain models that are usually great to get, but then there are one or two of those that just excel.

Rinaolo: Then again, the player’s going to make the difference. And the song you’re recording makes a difference in what amp sounds the best or what drums sound the best. And when you have more than a hundred choices … we’ve had guitarists sit in the middle of the room and line guitar amps around them and play until they find what they want to put on the track.

Nachodsky: In a lot of contemporary rock guitar music, there’s not often one guitar track per guitar player—there are layers. So even if you have the best sound ever, if you’re layering different parts on top of each other they might not stack up in a good way. A lot of times guys will come in with their rig, which will be great, but when we get to the fourth guitar track we’ll say, “You have to use something else.” Not necessarily for the tone but for the difference in tone.