When Kaki King started circulating a home-brewed CD of acoustic guitar instrumentals in 2002, she could hardly imagine it would lead to a record deal, national tours, and enthusiastic media attention. But the response to her music was so positive that the 23-year-old New Yorker suddenly found herself swimming in the deep end of the solo-guitar pool. Re-released in 2003 as Everybody Loves You, her self-produced debut featured a mind-blowing range of techniques. With its intricate, slapped-body percussion and overhand fretted melodies, the album’s opening track, “Kewpie Station,” heralded the arrival of a major new guitar talent. Though King had clearly absorbed ideas from Michael Hedges, Preston Reed, and Leo Kottke, her playing was distinctive and unique.

On her second album, 2004’s Legs to Make Us Longer, King began weaving other instrumentation into her music. The subtle sounds of cello, violin, upright bass, drums, and lap steel highlighted her skills as a composer and also signaled her desire to venture beyond the realm of solo guitar. King’s restless creativity became more evident on her next two albums, Until We Felt Red and Dreaming of Revenge. On both discs she played drums and percussion, bass and baritone guitars, keyboards, synthesizers, lap steel, and electric guitar. She also increasingly began featuring songs with lyrics and vocals. Some fans of her early solo acoustic guitar pieces were dismayed when they heard her loops and heavily textured sounds. But other listeners were drawn to the innovative spirit at the core of her music, and King’s audience continued to grow.

Given that history of musical morphing, it shouldn’t come as a surprise to discover that, once again, King has embraced change. On her latest album, Junior, King makes an abrupt shift away from the overdubbing approach she has pursued in recent years. Opting to record with a rhythm section, King enlisted drummer Jordan Perlson and multi-instrumentalist Dan Brantigan to lay down the basic tracks for Junior.

To learn more about these sessions—and to get the lowdown on her current tunings, gear, and songwriting approach—PG caught up with King on the final leg of an extended tour that included Australia, Europe, the UK, and the US.

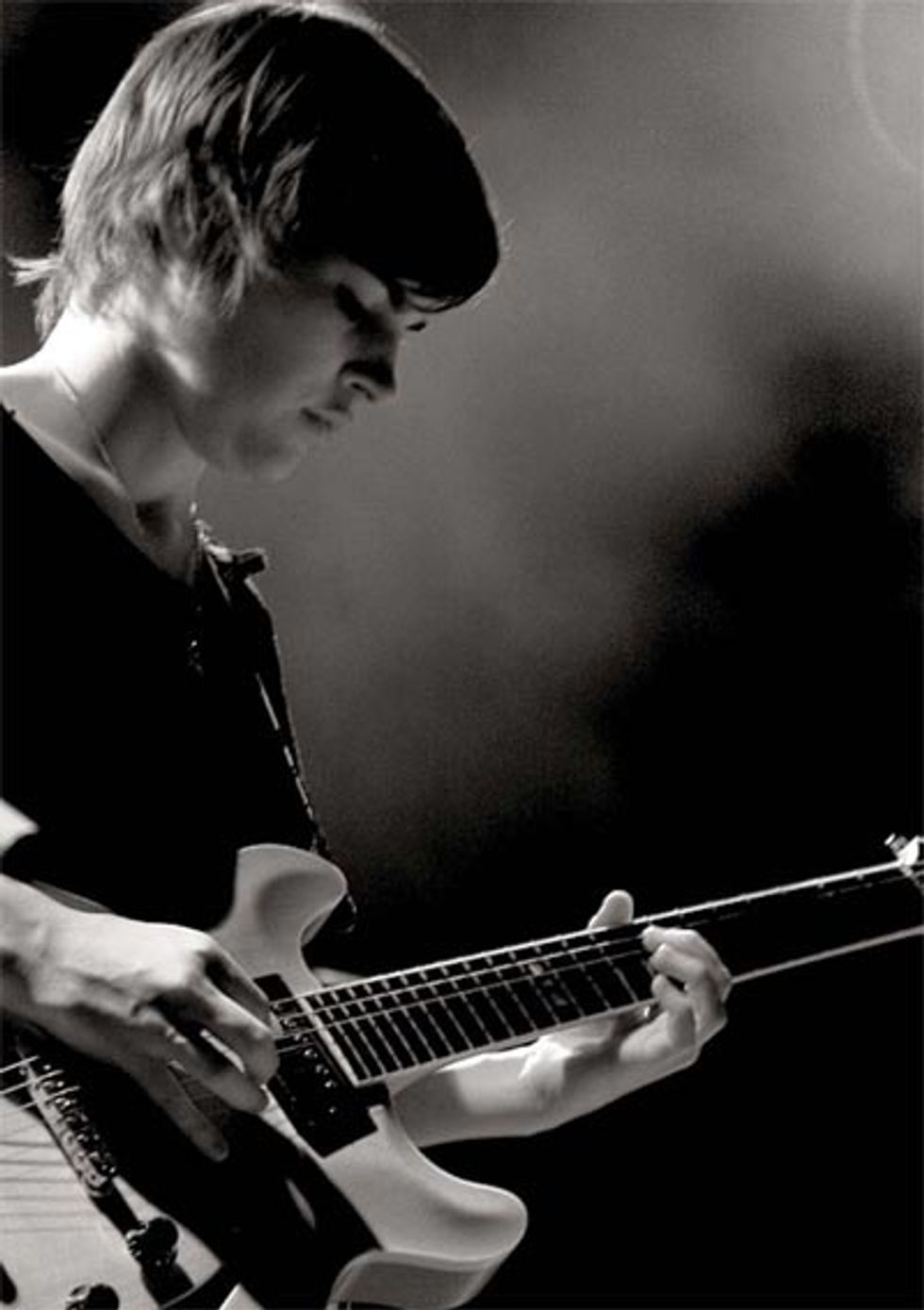

Drummer Jordan Perlson (left) and multi-instrumentalist Dan Brantigan (right) onstage with Kaki King and her 1972 Fender Telecaster Deluxe. Photo by Jennifer Ebhart

What prompted you to form a band to record Junior?

On my previous album, Dreaming of Revenge, I played most of the instruments myself, which meant layering bass, drums, and keyboards in addition to my guitars and lap steel. This time I wanted to try something I’d never done before, which was to put together a trio and cut the tracks as a group, live in the studio. Obviously, that’s the way many bands make their records, but for me it seemed like a real adventure. I feel it’s important to try new ideas and keep growing as a musician, and working with a trio was one way to accomplish that. This time, I relied on Jordan and Dan to help me arrange and develop the music—a very different approach for me.

Did you rehearse before going into the studio?

Yeah, and that was fun. I got together with Jordan and Dan, and for about three days we worked out the basic tracks in Jordan’s basement. I’d bring in ideas and we’d develop them as a group by jamming and trying out different arrangements. I liked getting input from the other musicians—it wasn’t my job to come up with all the ideas. For example, I wasn’t worried about finding the right drum parts or developing a groove. That was Jordan’s job. And of course, because these guys are amazing musicians, they’d come up with parts I wouldn’t have thought of, and that inspired me as a guitarist. Playing with a rhythm section I was able to explore lead lines and solos, and that was exciting, too.

Malcolm Burn produced Dreaming of Revenge, and you tapped him to produce Junior too. What drew you to work with him again?

We’d already gone through the process of learning how to communicate, and that’s important when making a record. When things get difficult in the studio, it’s good to know how someone will react to the situation. Plus, Malcolm has seen me struggle with ideas or parts, so I don’t feel self-conscious working on my vocals. We’ve developed the ability to trust each other’s creative process.

I’ve seen wonderful YouTube videos [The Making of Dreaming of Revenge, Vignettes 1-5] of you and Burn working in his studio, Le Maison Bleu. Did you return there to record Junior? With all the lamps and couches, it looks like an inviting space.

Yeah, it’s really cool. He has all these instruments and the environment is relaxed—more like a living room than a sterile studio. He has a lot of old analog equipment, too. Having a familiar place to record really helps, especially because I was trying this new trio approach.

Did you cut your band tracks live?

Except for “Sloan Shore” and “Sunnyside,” two songs I recorded solo, we cut the rhythm tracks live. Malcolm just mic’d us up and we went at it. Dan played bass with me and Jordan, and then later set up his EVI [Akai’s Electronic Valve Instrument, invented by Nyle Steiner] to overdub tracks of strange and beautiful sounds. The EVI is an electronic trumpet that Dan runs through all kinds of processing to create these amazing textures.

How long did you spend recording Junior?

Not long. We really didn’t want to labor over the music. We recorded as a trio for three days, and Dan came back for two days to add his EVI sounds. Then Malcolm and I spent probably a week and a half working on overdubs, developing lyrics, and doing some vocals. We took a break because he had another project, and then I came back for less than a week of singing and mixing. It felt like we worked relatively quickly, but then again, some people complete their albums in a week.

Photo by Jennifer Ebhart |

I have several Hamer Newports, and I used them a lot on this record. I really like playing a hollowbody electric, and the Newport is light and the right size for me. On “Sloan Shore,” I played Malcolm’s Fender Jaguar baritone. I was looking for a different sound and he suggested I try it. Though he had it tuned down in the bass register, it has the sonic clarity of a guitar—it gave me a bit of both worlds. I also played my Gretsch Electromatic lap steel, which first appeared on Legs to Make Us Longer.

How about amps?

Malcolm has a nice collection of recording amps, so I used whatever he’d set up. I didn’t pay much attention to what they were, but I recall one was an old Ampeg. [For details on King’s amp rig, see our conversation with Malcom on p. 3]

Did you get involved with mixing?

Yeah, certainly. I leave it up to Malcolm to do the first mix, and then I’ll respond to that. If I want to hear more of a particular part, I’ll ask him to emphasize it. But it can get tricky because he doesn’t do any digital mixing at all. He does each mix manually— it’s almost like this dance he does with the faders—and every one is different. So if I want to hear a little more guitar 30 seconds into the song, he has to reconstruct an entire mix. It’s a dangerous game, so I have to live with some things I might prefer to hear a bit differently.

Describe how you wrote the songs for this album.

It was a bit unusual, in that I wrote almost all the lyrics and many of the vocal melodies in the studio after we’d laid down the rhythm tracks as a trio. We came in with grooves and arrangements, which had evolved from ideas I’d brought to the band, but the songs themselves took shape as Malcolm and I worked on them after tracking with the trio. Every night, he’d give me a mix of what we’d done musically—a little compilation of soundtracks, basically. I’d take them home, stay up late and write lyrics, and then try them out during one of the next vocal sessions. Some people keep notebooks full of potential lyrics, but I never found that to be very helpful, though I do keep a journal. Occasionally, when something brilliant comes out of someone’s mouth or I hear something I want to remember, I’ll jot it down. But for the most part, I prefer to react spontaneously to the music we’ve just recorded. Sometimes Malcolm would set up a mic and I’d sing some lyric fragments, and we’d develop the ideas right there.

Open and altered tunings have played a central role in your previous records. Was this also true of Junior?

Every song except “Sunnyside” was in an open tuning of some sort.

Were these favorite tunings you’ve used before or were they discoveries you made while writing for this album?

Some are favorites, but often I’ll think, “Let’s see what happens if I lower this string here and raise that one there.” I often find my hands can get locked into formations they’re familiar with. When you tune your guitar differently, all of a sudden your fingers and your mind have to be creative again because you’re not relying on shapes and places that sound good or feel familiar. You have to explore the fretboard to find new fingerings and sounds, and that leads to new discoveries.

How do you keep track of your tunings?

Now that I’m playing with a band and everybody has to be in tune with each other, I actually have a guitar tech, Anna Morsett, and she does all my tunings for me [laughs]. If you want to know what they are, you’ll have to ask her. It’s especially important when we’re switching tunings from song to song. If I retune the same guitar to something radically different onstage, I can just feel the audience energy start to taper off and off and off. When Anna hands me a guitar that’s already tuned up, we can keep the momentum of our performance. It’s a big improvement.

How many guitars does it take to stay on top of all your tunings?

Right now we’re doing a two-hour show and, not counting the lap steel, I use four guitars.

Do you use more than four tunings? Does Anna retune some of those guitars while you’re playing?

Oh yeah—I use lots more than four tunings. Probably ten per show.

Kaki King’s guitar tech, Anna Morsett, keeps her stage guitars strung, tuned, and ready to play. She uses .012-.053 Elixir Polywebs on King’s acoustic guitars and .010-.046 Nanowebs on King’s electrics. The following chart lists the 10 tunings King used most on her latest tour. (6-5-4-3-2-1)

“Bone Chaos in the Castle” - C# A# C# F A# C#

“Pull Me Out Alive” - B B C# F# B C#

“Montreal” - E B C# G# B D#

“Everything Has an End, Even Sadness” - E G E G B D

“Death Head” - C# G# C# F A# C#

“Jessica” - E A D G B D#

“Can Anyone Who Has Heard This Music Really Be a Bad Person?” - C# G# C# E B D#

“Doing the Wrong Thing” - E G D F# B F#

“Playing with Pink Noise” - C G D G A D

Are you playing your Hamer Newports onstage?

I do have some Newports, but because I needed something with a little more oomph, I bought a 1972 Fender Telecaster Deluxe for playing on the road with the band. It’s really great for what we’re doing. I run it through a Fender Bassman.

Do you use the Bassman just for your Tele or for all your guitars?

For everything except my Adamas acoustic, which goes directly into the house system.

Has your signature model 1581-KK Adamas changed or evolved since it was introduced?

I think we changed the bridge wood, but other than little cosmetic things, nothing major. I usually carry several on the road, but because I’m playing more electric guitar right now, I just bring one with me.

Tell us about your pedals.

My pedalboard is always in a state of flux, but currently I’m using an Ernie Ball volume pedal for swells and a simple Boss DD-3 for delay. I also have a Boss TR-2 Tremolo pedal and a Boss OC-3 Super Octave pedal, and a Fulltone OCD distortion pedal. For weird sounds, I’ll sometimes use my Electro- Harmonix Harmonic Octave Generator.

You have amazingly long fingernails. What’s the story there?

Like many guitarists, I go to a nail salon and get acrylic overlays on my fingernails. The difference is I get them really thick. Thick nails sound different—it’s like a thin flatpick versus a thick one. If the acrylic nail is too thin, it sounds funny. I shape the acrylic overlays myself, flattening out the bottom surface. I grow my thumbnail out because when I pluck a string, my thumb is almost parallel to it. The angle requires a long nail to catch the string. That’s an acrylic overlay on my thumbnail, too.

Who are you currently listening to for musical inspiration?

I’m listening to a lot of Brazilian music: Bebel Gilberto, Virginia Rodrigues, and Rosa Passos. I know it’s not really apparent in my own music, but it’s something I like.

What’s next for Kaki King?

I’ve been on the road for four months straight. In another three weeks, we’ll be done with this tour. Honestly, that’s about as far as I can see.

Kaki King recorded this year’s Junior and 2008’s Dreaming of Revenge at Le Maison Bleu, a studio near Woodstock, New York, that’s owned by Malcolm Burn. While Burn produced both discs and 2008’s Dreaming was essentially a collaboration between King and him, Junior was a band project.

“I think, conceptually, Kaki felt she wanted to make a recording that could be taken out on the road and recreated,” says Burn. “There were a few tracks on the last record that featured a lot of orchestration. To perform them live, Kaki had to get a little five-piece orchestra together to get the point across. Touring is her bread-and-butter, so this time she wanted to record music that could translate easily from the studio to the stage. My only concern going into this project was that her guitar remained central to her music and didn’t get overshadowed by the drummer’s virtuosity. Her guitar is half the reason people buy and listen to her records, so I didn’t want anything to take away from the intricacy of her performances.”

Burn used a dual-amp rig for many of the electric-guitar parts King tracked live with the band. “I ran a Fender Super Reverb, set pretty loud and clean, in tandem with an old Gibson Skylark 1x10 combo,” he details. “I plugged Kaki’s guitar into the Skylark and then ran a jumper cord out from the Skylark’s second input jack into the Super Reverb’s input. For overdubs, we also used an Ampeg Gemini combo.

“I used Sennheiser MD 409 dynamic mics on the amps. To mic Kaki’s acoustic, I’ll typically use a Neumann U 67. On Junior, I mostly used a Neumann U 47 for her vocals, but in the past we’ve also used a Sony C-37A. I generally favor API and Calrec mic preamps, and I’m also a big fan of those funky little Bellari MP105 tube preamps.

“I’m running a Pro Tools HD system, but mentally I treat the computer like a 24-track tape machine with a dedicated hardware channel connected to a respective Pro Tools track. Each track’s output has a channel on my big analog console, which was made by an offshoot of Amek. I try to stay away from the internal processing aspect of Pro Tools—all the plug-ins and stuff. I really don’t have the time, patience, or energy for that—or the gullibility to believe that plug-ins will make my record sound a whole lot better. Apart from the occasional de-esser plug-in, I use outboard effects. I’ll use automation when I have to, but I prefer to mix a song manually. This way, each mix becomes a performance. I think this technique is still valid because it allows you to spontaneously come up with something you hadn’t thought of, as opposed to preconceiving the sonic outcome and just working toward that inevitability. It’s a more painterly approach, I suppose.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)