Nylon-string sensations Rodrigo y Gabriela were out of gas in a dead-end Mexican metal scene until they ditched their band and relocated to Ireland for four years of intense street training. Now they’re global stars racking up millions of views on YouTube and making late-night talk show appearances with their signature Yamaha guitars. I’ll never forget the first time I heard Rodrigo y Gabriela. I was listening to NPR’s World Café segment, and I was immediately enamored with their unique approach to nylon-string guitar. I pulled the car over to the shoulder of the road and sat there for the next 30 minutes, listening to them explain their craft and rip through original instrumental compositions and an incredible rendition of the Metallica classic “Orion.” I was late for work, but it didn’t matter. It’s not often that you hear a musical group that grabs you and won’t let go the instant you hear them.

If they’re new to you, what you need to know is that Rodrigo Sanchez and Gabriela Quintero have made a name for themselves by melding traditional world music with the dynamics and aggression of heavy metal. To make up for the lack of drums and bass, Quintero has developed an exceptional method of hand percussion that relies on striking both fretted strings and carefully chosen parts of the guitar with an attack that can be downright vicious. She’s basically a one-woman rhythm section. Sanchez, on the other hand, plays ’80s-shred-style riffs and leads mixed with a heavy dose of South American and Middle Eastern fl avors.

The duo originally met in Mexico City. Both played in a thrash metal band called Tierra Acida, but their frustration with the narrow range of music being followed in the area led them to pack up and head for Europe. They eventually settled near Dublin, Ireland, where they spent countless hours busking on the street. Naturally, their electric instruments weren’t really suited to the task, so they adopted the simple setup of two acoustic guitars. Over time, Sanchez and Quintero’s distinctive sound came together as a natural result of struggling to make the guitars communicate the dynamics of their eclectic backgrounds.

Since then, Rodrigo y Gabriela’s popularity has exploded. They’ve made appearances on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno and The Late Late Show with Craig Ferguson, and at press time their version of “Stairway to Heaven” had nearly six million views on YouTube. Their latest album, 11:11, serves up 11 jaw-dropping tunes, including “Atman,” which features a guest appearance by Alex Skolnick (Testament, Trans-Siberian Orchestra)—who was a major influence on Quintero and Sanchez’s music. We recently caught up with the duo during a tour run that was so hectic that we only had limited time to spend with Quintero (who’s one of the nicest people we’ve ever interviewed, we might add). Here they discuss with us their inimitable songwriting, their new signature Yamaha acoustic guitars, and the intricacies of their playing styles and techniques.

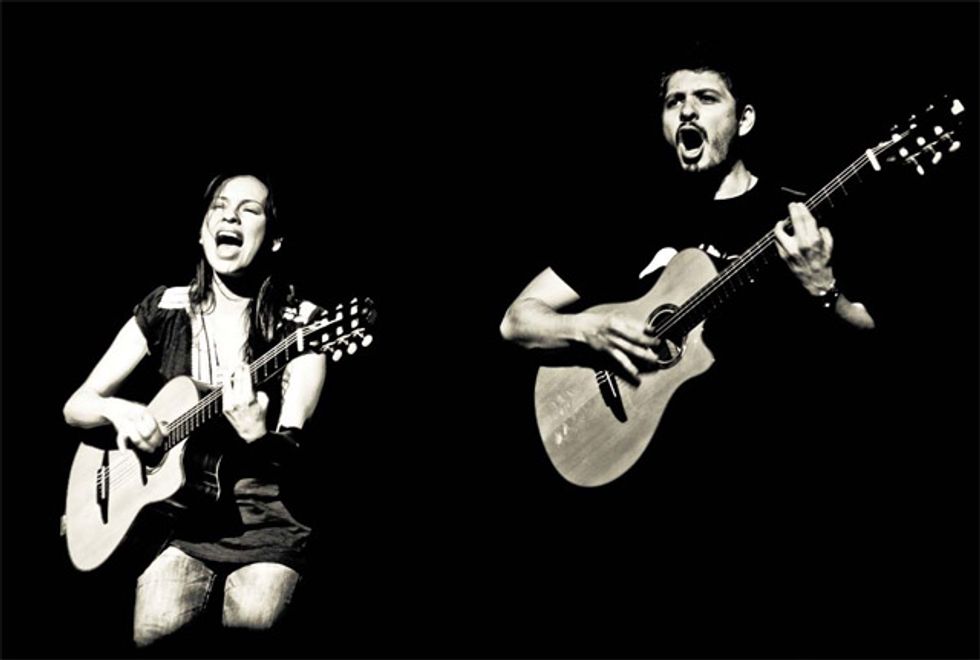

Gabriela Quintero and Rodrigo Sanchez onstage with their signature Yamaha NCX and NTX nylon-strings. Photo by Vince Kmeron

A lot of people confuse your music with flamenco. What do you say when they make that assumption?

Sanchez: I can understand why some people confuse our music with flamenco. I mean, they see nylon string guitars and they just automatically make the assumption. What we do is a mix of rhythms that we have put together in a very organic way, something that we didn’t really plan originally. While we were playing on the streets of Europe, we started to compose music that was more naturally suited to the instruments we had. Yet we felt like we couldn’t just forget all of the years we spent playing metal. So we adopted rhythms from that style of music into what we have now, and I don’t think that even I could tell you what it would be called [laughs].

Quintero: Most of the music we draw from is just music we love to hear. Lately, we’ve been listening to a lot of reggae, classical, and jazz, with a lot of rock from the ’60s. We’ve also been listening to a lot of metal, which we genuinely love. So when we listen to those forms of music, we like to adapt those rhythms to make our own music more diverse. I think, in the end, what we really play is rock music—because we aren’t jazz or classical musicians, but we try to take those influences and add them to our own music.

What prompted you to move to Ireland?

Sanchez: Our heavy metal band, Tierra Acida, didn’t succeed and we figured our chances of getting a record deal were over. We were tired of chasing after one, and the only thing that we knew for sure was that we just wanted to play music. It didn’t matter if we were playing background music or bar music. So we moved to Europe. To make the move easier and lighten the load, we decided to sell all of our electric instruments and travel with two cheap acoustic guitars. We were much younger, and we did that for about four years before we came back to Mexico. It was great! We made a good living, and then our music started developing more naturally. I suppose sometimes you need to detach yourself from chasing a goal that you’d die for. Then you can focus on and enjoy what really made you want it in the first place.

Do you think stripping down your rig challenged you to write better material than you had before?

Sanchez: Well, a lot of the riffs that we play could actually be played with distorted electric guitar. What happens, though, is that a lot of people don’t notice that—because not very many people really understand heavy metal. The metalheads definitely get it, and a lot of our crowd comes from that world. It’s great that when we combine that style with ours, it works out really well.

What are some of the challenges of making sure key aspects of that metal feel translate to two acoustic guitars?

Sanchez: The structure of the pieces is already kind of based in a standard rock form, so the standard layout of the intro, bridge, melody, and solo weren’t things we really changed up that much. It might be hidden to some people, but for others that might be why it’s so appealing to them. They’re instrumentals, but the melody takes the place of where the vocals would normally be. Gabriela also had to develop her rhythm style on her own, because she didn’t have any formal training. She didn’t have the chance to learn from somebody with flamenco experience or study with someone who knew South American rhythms that are centuries old. Since we didn’t go to any sort of music school, she just came up with her style on her own, out of the need to keep the feel that we were still in a full band. She felt the need to take care of the drums and bass, while I covered the guitar and vocal parts. It just took off naturally at that point. There was never a moment where we said, “Okay, let’s play this metal thing here and translate it into Celtic or whatever.” The whole sound just came out of necessity, because of the style of music that we knew how to play—and loved playing. It was kind of accidental, actually.

What’s one of the biggest misconceptions of your style of music?

Sanchez: The biggest is definitely the flamenco thing. Another one could be that we play traditional Mexican style, which it isn’t either. It’s far from it. We kind of understand now that people will think or believe what they want to about our music, but it’s important to clarify, just in case people go to our concerts and expect to hear flamenco or Mexican music. We don’t want them to get the wrong idea, you know?

11:11 is more experimental than some of your past records. The core Rod and Gab sound is still there, but you’ve also added stuff like the wah pedal and that riff in “Logos”—which sounds a little like the outro on Pantera’s “Floods” or the riff to Metallica’s “One.”

Sanchez: You know, at the time I thought we were going a little too far from what the first album was like. But I kind of regret that we didn’t experiment just a little more. For the live shows, though, we’ll use more effects, such as wah and even some distortion. It makes sense when you know the people who go to our live shows, as opposed to those who just listen to the album. With 11:11, the whole approach was totally different than the ones before it. We were excited that we were going to work with producer John Leckie [John Lennon, Radiohead, Pink Floyd], and we did some demos with him when he arrived. The demos ended up sounding exactly like the first album, and we didn’t want to do that. We also knew that we were going to work with Colin Richardson mixing, but we wanted to do it our own way too. We wanted to go back to the way that we recorded our metal band in the ’90s, doing things like doubling our guitars and using other older techniques. There was a more clinical approach to the recording, which is what we were after. I think if we had more time, we would have added more parts. During the live show, we add additional parts and textures, though. So in retrospect, I guess I’m glad we didn’t add them in the studio, because that saves some of the tricks for the next album.

A lot of your songs have that sort of classical-intro style that a lot of ’80s metal bands used. Which bands or albums influenced your songwriting in that regard?

A lot of your songs have that sort of classical-intro style that a lot of ’80s metal bands used. Which bands or albums influenced your songwriting in that regard?Sanchez: We got that from ’80s thrash metal bands like Metallica. Their intros to songs like “Battery” or “Fight Fire with Fire” contained elements that were translated from classical guitar. When I first started writing metal songs as a kid, I added that to my composing skills. If there was one album that made a huge impact on me in that way, it would be Testament’s The New Order. That’s how I became a huge fan of Alex Skolnick. What fascinated me were these massive pieces of intricate music before the heavy part came in. It just seemed so mysterious and well executed. There are other genres of music that we blend together and they all have their own aspects that we like to concentrate on, but that’s certainly the one for metal.

Quintero: I guess what it really comes down to is what we think we can play well. We prefer to keep the sound really tight, which comes down to this type of structure. That also really helps people relate with our music, because it is not a jam-type of music, where it takes two hours or something like that to do a solo. I don’t think that we can do that! [Laughs.] We like to stick to what we do best.

Every song on 11:11 is dedicated to a musician. How did those dedications affect how you wrote the songs?

Sanchez: When we were writing the songs, some of the people we dedicated them to were already in our minds. Some were afterthoughts. That’s because it took a good while to select 11 artists that we both love equally. There is not an act in there that I liked more than Gab, and the other way around. We already had some of the melodies written before some of the acts were chosen, but when we actually started working some of the material changed a bit. A good example would be the title song, “11:11.” We knew we had to dedicate a track to Pink Floyd, so we already had the idea to do something more spacey and open—the Pink Floyd kind of vibe, you know? Some of the tracks, such as “Triveni,” had nothing to do with the dedicated artist’s type of music. That one is dedicated to Le Trio Joubran from Palestine, and it’s totally a Latin influenced track. However, they did inspire pretty much all of the Middle Eastern sound that’s present throughout the entire album. Songs such as “Atman,” which is dedicated to the late Pantera guitarist “Dimebag” Darrell Abbott, has Le Trio Joubran’s influence all over it. They inspired us to write those types of harmonies and melodies for a lot of the music that we write. At the end of the day, though, we just adapted everything for what we thought was best for each track.

Let’s talk gear for a moment. You guys recently collaborated with Yamaha on the NCX and NTX guitar lines, which are based on their grand concert designs. What sort of input did you provide on those?

Sanchez: Yamaha pretty much followed us for about two years and made us loads of prototypes until we were happy. We gave them all of the measurements from the guitars we were used to playing with—which were also Yamahas. They were more from the classical end of things, with that kind of look and feel. Mine had a very nice neck with a really thin body. We used those guitars for a few years while we were busking, and then when we started playing larger, more proper gigs in Ireland we were approached by a local Irish luthier named Frank Tate. He said he had been building instruments for a while and that he wanted to build our guitars. We told him we were very comfortable with our Yamahas and that we didn’t want to lose the shape, size, and measurements of those instruments. He was free to use any type of wood that he thought would be a good fit, just as long as the measurements of our Yamahas were there. And the guitars he built us were great—acoustically they sounded really good. We still have them, in fact. The only problem with them was that the electronics were weak, and it really started to show when we started playing bigger venues. Since Gabriela plays the top of the guitar with her hands, her guitar tone has to be two separate signals, one from the electric pickup and a mic from the top of the guitar. It got pretty complicated after a while. So, Yamaha approached us at just the right moment.

The main difference now is the electronics—they ended up making an entirely new pickup system. They knew what our needs were and they worked with our sound engineer to get it just right. The system is made up of a lot of piezo pickups, more than just one or two. Gabriela’s guitar, for example, has seven piezos. Mine has five. Also, I like really, really low action. Gab’s is the same way. When I played electric guitar, I had a really thin neck, so the neck on my Yamaha is really thin, too. Probably as thin as you can get on an acoustic guitar, with the action being as low as you can get, too. My guitar also has 24 frets, which is a big difference. Gab’s guitar has more of a classical body shape. Of course, they both have cutaways. They were really dedicated to giving us what we wanted.

Quintero: Yeah, in our studio back in Mexico, we like to keep our playing strictly to acoustic guitars. We find that a lot of natural elements and sounds come out that way. The idea was to properly translate those sounds in the studio to a big PA setup, to take those acoustic sounds and move them to a rock-band volume level. My requirements for the Yamaha engineers were that the guitars had to avoid feedback, keep the clarity of my percussion parts, and have big bass frequencies. So they put a lot of piezo pickups in the tops of the guitars to pick up the percussion. My guitar has seven spread out across the top of the guitar, so no matter where I hit, it will sound out loud through the PA. They’re always coming up with something new for us, because sometimes we come up with different parts and it ends up being a problem for the sound guy. Then everybody cries and it’s a mess! [laughs] They’ll send one guitar after another, just because they keep developing new things.

Did you use the new Yamahas to record 11:11?

Sanchez: Some parts of the album were recorded with them, and some parts were actually recorded with the old Irish acoustic guitars—because some of the parts needed more acoustic-sounding tones. The new Yamahas are great, but they’re better for live situations, for big PAs and all that.

What kind of strings and picks do you use?

Sanchez: We use medium-gauge D’Addario nylon strings—we’ve used them for years. My picks are the small Dunlop Jazz III picks.

What were your favorite moments from the 11:11 sessions?

Sanchez: I think the best thing was working with Colin Richardson. We were mixing the record in the studio with my engineer—sometimes for 17 hours a day—over the course of five months. It was great, we were using Skype with Colin, and he was sending us the mixes that he was working on. We’d send a pre-mix to him, so he’d get an idea of what we wanted, in terms of panning and all that. We’d finish a song every week or 10 days, fully recorded and mixed to our liking. Then we’d send it to Colin in England and he’d work the track over and send it back with different alternatives and different we’d send a really rough track in and when we’d open the file that he’d send back, the sound would be massive. It was always really surprising in terms of the overall sound, and we’d look forward to getting a new mix from him every time.

Gabriela, what inspired your percussion style—and what did you do to perfect it?

Quintero: Actually, that technique was almost completely inspired by flamenco music. I’ve always been thrilled by the way flamenco players play rhythms with their right hand—it’s so incredible. I didn’t have any clue how to do it at all. Eventually, I met a flamenco player who taught me one movement, and that was it. I practiced it a lot and tried to copy what other flamenco players did, but I never got it right. Nowadays, I still don’t know how they do it.

We saw some flamenco players in Barcelona years ago, and they had a completely different rhythm style than I have. That’s when I realized my rhythms weren’t like theirs at all and that they sounded “rockier” and far more aggressive. I like it my way more, you know? [Laughs.] I also realized they use their thumb for a plectrum, which makes everything completely different. After that, I discovered some players in parts of Mexico that used really colorful scales that aren’t used that often, and I just adapted some of that and gave it more volume. I never realized while I was living in Mexico that some traditional Mexican music could be so colorful until then. So, basically, all the rhythms that I use I came up with on my own. But I would like to learn how to play traditional flamenco at some point. I just love that music.

Where would you suggest other guitarists start if they want to learn this style?

Quintero: I wouldn’t recommend taking lessons, because the learning experience should feel a little more free than that. If somebody really wants to learn that style, they should go live in the caves. [Laughs.] Don’t take any lessons. Just learn it on your own as you would a language, and then after you’ve got your own feel for it you can go back and take lessons. That’s actually something that I would like to do when I’m not busy—just live away from everybody else like a wild monkey and learn.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)