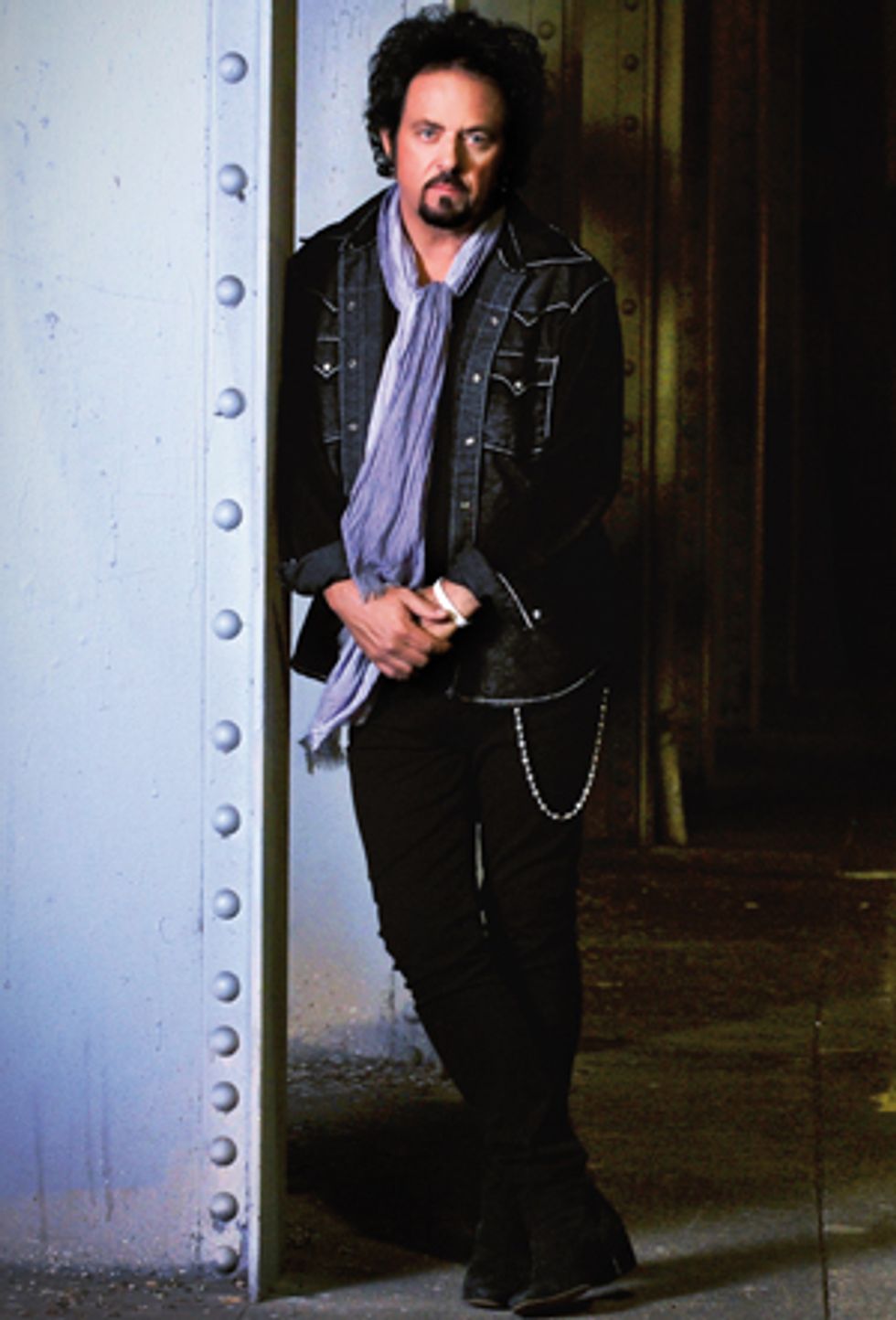

For a guy who’s allegedly been referred to as the “world’s greatest guitar player” by Eddie Van Halen, who’s played the immortal intro to Michael Jackson’s timeless hit “Beat It,” as well as having played guitar on virtually every major label pop hit out there, you would think that five-time Grammy winner Steve Lukather, aka Luke, would have an impenetrable ego of steel. Fact is, even Luke hurts. The guitar legend unabashedly wears his heart on his sleeve and his new solo album, Transition, is a catharsis of sorts on many levels.

“The internet can be pretty cruel, man. People will try to point out your weakest flaws physically, or about your playing. They catch you at your weakest moment and you’re like a piñata with a baseball bat,” says Luke. “I’ve taken 36 years of criticism. Things like, ‘Our parents should have been sterilized so we can never play the shit music that we make.’ I’ve heard them all.” To respond, Luke (along with co-producer CJ Vanston and Fee Waybill) penned “Creep Motel” and “Judgement Day,” which feature lyrics like “It finally hits, you're full of shit, your tiny fingers dancing on your keys of hate.”

Transition also addresses several major turning points in Luke’s personal life. Songs like “Once Again” see him offering an honest and heartfelt reflection on his recent divorce and, the closer, a first-take instrumental rendition of Charlie Chaplin’s “Smile,” pays tribute to his mother, who recently passed away (“Smile” was her favorite song). The album features an all-star cast of A-list musicians including Tal Wilkenfeld, Chad Smith (Red Hot Chili Peppers), and Phil Collen (Def Leppard), among others, and was written and recorded during an impossibly hectic 10-month period that saw Luke go on five, yes five, major tours. Luke breaks it down, “On January 1, I went to Germany to do this Rock Meets Classic tour with Ian Gillan from Deep Purple and some other people, including an 80-piece orchestra. Then I went out and did G3 with Joe Satriani and Steve Vai, which I was very honored to be asked to do. Then I went out with Ringo Starr all summer, and then I went out with Toto. I then went back out with G3 but with John Petrucci instead of Steve Vai. The whole time I was writing and mixing. That’s the short version. I wasn’t sittin’ around doin’ nothin’ for the year, I can tell you that.”

Luke takes us inside the making of Transition, explains his pared-down setup, gives the scoop on his new signature Ernie Ball/Music Man Luke III model —which features his new DiMarzio Transition pickups—and shares his take on the new face of the music industry.

I understand that you took a different approach to writing Transition.

I did it in a weird sort of way. I usually write songs and go in to cut basic tracks. On this one, I thought I was going to make little demos but the demos turned out to be really good. I realized that we didn't need to do it again. I said, “Let’s keep all this and just add people to it,” so we started adding real musicians to it as the songs were finished. I’d never done it that way before but it allowed me to cast the record like a director would cast a film. I could get what I thought were the right players for the songs and they really knew what they were playing to. Oddly enough, the way the album is sequenced is the order in which the songs were written.

”Transition,” the title track, has so many different sections that it’s almost like a prog-fusion odyssey. How was that one put together?

That was written with Steve Weingart as well as CJ [Vanston]. We had no rules. I originally intended to write an instrumental piece, which it ended up not being. I added some vocals. But I have a great love for ’70s prog rock like Yes or Genesis. I’m not trying to write hit songs, I’m trying to make an artistic statement. I just want to make a record that I enjoy listening to and so far the reaction has been pretty good. Having a record label give me that freedom—they didn’t hear anything until I turned in the mastered record. They trusted me and I try to deliver stuff that’s accessible yet still a little harmonically challenging. I’m not trying to write full-on fusion, freak-out music. Math music [Laughs], for lack of a better term.

But “Transition” goes beyond the confines of 4/4.

Yeah, it was in 7 I think. It’s not that whacked-out by today’s standards. I still don’t want to just write clichéd power-chord music. There are some guys that write music that’s so crazy that it makes me laugh out loud. It’s so cool but it’s like, “Wow, what is that.” I like to think that I’m fairly well versed but there are some young cats out there that are just blowing the roof off. I love it, man.

Tell me about “Creep Motel” and “Judgement Day.”

Those two songs are like bookends. They’re about internet haters—people sitting in their little rooms hating everybody. Hate breeds hate. I’m a really sensitive person and it really [expletive] with my head. I’m of clear mind, body, and soul, and have been for years, but there was a time in the mid-2000s where as a player, I lost my way, and I’m rather ashamed that some of these performances have found their way to the internet. And the worse they are, the more people see them, and the more they want to [harass] me about things that happened years ago. It’s really insidious. What’s next, you walk into a room and there’s a hologram of a “Like” and “Dislike” next to you, and if too many people point to the “Dislike,” you’re thrown out of the room? It’s like this Orwellian bullsh*t, hyper-critical society now. People won't even get up and jam anymore. They’re afraid everybody’s camera is out. You get this feeling of unrealistic perfection that you’re supposed to attain every time you play, sing, or do anything. It’s really screwed up. And these are the same people that come up to you and tell you, “Hey man, really nice to meet you.” They’re the same people with a fake name.

Well, haters are gonna hate, but why do you care? You’ve enjoyed an illustrious career that the majority of guitarists out there could never imagine having.

Wait a second, I’m not saying that I sit around worrying about this. But it does hurt if somebody comes up and is really mean to you. I’m a sensitive person. “I hate you. You suck. You’re ugly. You sloppy piece of [expletive]. Overrated [expletive] hack,” whatever they want to write about me. It’s still like, “Wow, man. I don’t even know you. Why would you say that to me? That hurt my feelings.” It’s not a matter of whether it’s true or not. When you’re in the public eye, that’s part of the beating. Look at the society we live in now. People think that entertainment is tuning in and watching people emotionally die on television, while they eat popcorn. Reality TV. I don’t find it entertaining. I don’t find it a positive thing. I’m an old-school guy. Peace and love. I go out with Ringo and it’s all about keeping that vibe alive. Maybe I’m a corny old guy.

Do you go on the forums yourself to see what people are saying?

l try to avoid them but sometimes people feel this need to show me things. I don't go looking for these things but sometimes people put them on my Facebook page. “Look what so and so said,” and just like anything else, curiosity killed the cat, and you press the button and you read and you go, “What was that?”

I went through a really dark period of time where I kind of lost my way as a musician and a human being. You know, 36 years on the road makes a man crazy. And there are some less than flattering performances out there because I was drunk or pissed off, and I was playing too much because I was angry that my personal life had fallen apart. You have a tendency to play how you feel.

What guitars are you using on Transition?

It’s the same guitar on the whole record: The new LIII Music Man guitar with DiMarzio signature Transition passive pickups made especially for me.

As opposed to your previous Luke signature model’s active HSS configuration, the LIII is a passive dual-humbucker model. How do you get some of those Jimi-like Strat sounds on the record?

You can split them out, there’s a 5-position switch on it. That’s one of the cool things about the guitar, it’s got all these different tones. I still have that guitar [the Luke] but I just didn’t use it on this record. They also made me one with two single-coils and a humbucker, and I used those two guitars on the record. I just wanted to be a little bit more fat and organic. A lot of people dug my guitars but they didn’t dig the EMG pickups—EMG makes great stuff, I’m not putting them down. I used them for years; I was one of the first guys in the ’70s to use them. The good thing about the internet is that I listen to constructive criticism. People would say things like, “I like your guitar but the body’s too small,” or “I don’t like EMG pickups,” or “I like passive pickups.” As I became more organic as a person I wanted to become more organic with my sound. I don’t use any digital gear or MIDI crap. I plugged into a Bogner Ecstasy and a volume pedal, and any and all effects were done with plug-ins after the fact. I wanted to keep as clean a signal path as possible.

That’s a big contrast from the processed L.A. sound, which you pioneered and that was so in vogue that the A-listers employed carting companies to lug their racks of gear into the studio for sessions.

What was that, 1984? 1985? I’m still getting punished for sh*t that I did 30 years ago. That was the sound of the ’80s. The ’80s was the decade of excess. You get all this new stuff, you play on a hit record, and everybody copies it. All of a sudden they want you to play this sound when they hire you and that becomes your sound. People would go, “That’s Lukather’s sound.” I’d go to a NAMM show and there’d be a processor and I’d press it and it would say, “Luke,” and it sounded like flanger and echo returns, and I’d go, “Dude, what the … ?” That’s not what I sound like.

I was a little bit resentful of that carrying me 25 years later when I really don’t sound like that anymore. I mean, come on, are you going to make fun of my mullet, my drug habit, and the rest of the stuff that went down? I was just doing what everybody else was doing and that was probably the problem.

Although you’ve kept it fairly straightforward, you also used a little bit of the Kemper Profiling Amp on this album.

I did. I got it as a gift. This cat Brian Moritz sent it to me. I used it on a couple of clean sounds. On the song, “Right the Wrong,” for the dreamy clean sound, I plugged right into the thing. That was the first sound that came out of it and that kind of inspired the song. As far as profiling amps, I think the Kemper is one of the best ones I ever heard. But in general, I still like the reality of tubes.

Have you compared it to the Fractal Audio Axe-Fx?

Not yet, no. I’d love to tell you I’m this big gearhead but I’m really not. Things come to me and I go, “That’s really cool,” or, “I don’t like that.” I have people sending me all these cool little pedals and I’ll put them on my pedalboard now but the board consists of nothing but stompboxes. It’s really old school.

What do you have on the board?

Just different little things. I have a HardWire delay, I got the T-Rex stuff, I got some Strymon pedals. They make some really great stuff like that little blue reverb unit [blueSky Reverberator], and the Lex Leslie simulator is really great. I use that on the Ringo stuff like “It Don’t Come Easy.” Bonamassa gave me a wah-wah pedal. I’m working on a wah-wah pedal and a delay with T-Rex right now.

In the past, the recipe for success as a session player might have been to get your rhythm playing and reading together, and network like crazy. However, the industry has changed considerably. What would you be doing in terms of forging a career if you were just starting out now?

Aw man, it’s scary. It’s a brutal business, man, from a financial aspect. How do you monetize this and what people want in return for what you give them. There’s no session thing anymore. There’s no young session guy that I know of. There’s nobody coming up because there’s no work for them. I mean there’s people that play on records but most people’s budgets are cut to like 1/100th of what they used to be. People figure, “I can do this good enough myself and put it on the grid and tune it up.” They have technology now where they can take a Rolling Stones track and Melodyne everything into a Steely Dan album. I was at a party with Lee Ritenour, Ray Parker, Jay Graydon, and all the old ’70s and ’80s session guys, and Clarence McDonald, one of the old keyboard players said, “Now they have ProTools. It used to be just pros.”

Do you feel that there is something lacking with the over-reliance on technology?

The thing that’s missing is the interplay that would accidentally happen on sessions when you get great musicians in the room listening and playing off each other. Things would happen that you can’t program. But I don’t know if anybody cares anymore, that’s the really sad part. I make records as if they do. If you put the headphones on, you’ll hear a bunch of shit that you normally wouldn’t hear. A lot of people think of music as just background music to multitask to. They’re not really paying attention to it because they’re doing 10 different things at once.

Steve Lukather’s Gear

Guitars

Ernie Ball/Music Man LIII with DiMarzio Transition signature pickups, Ernie Ball/Music Man Luke

Amps

Bogner Ecstasy, Kemper Profiling Amplifier

Effects

Dave Friedman pedalboard, Strymon blueSky Reverberator, Strymon Lex Rotary, HardWire DL-8 Delay/Looper, HardWire tuner, Dunlop Joe Bonamassa Cry Baby wah

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

Ernie Ball Cobalt .009s and .010s, Dunlop Jazz heavy picks, Mogami and Monster cables

Your son Trevor plays on “Right the Wrong.” He can’t really follow in your footsteps because the industry has changed so much. What advice do you give him?

It’s not the same business. Now he’s doing sessions for people that I used to work for but they don’t pay as much anymore. He’ll write songs for people and get burned by them. The record companies burn him, there’s just more thievery now than there ever was. He’s been offered these deals to go on these corny, karaoke television shows. But you go on these shows and if you don’t do well for whatever reason, your career is over, man. And you sign your life away for five years and they own you, so even if you win, you lose. I told him, “If you sign that deal, I will disown you. You have to look at the long haul. You want to be the tortoise or the hare? You want to be the tortoise. You want to be the guy that wins the race but just takes his time getting there.” That’s the way I’ve led my life and my career. I always said to myself, “They can make rock stars—just add water or add booze.” But a long career as a musician is all I ever wanted in life and I got 36 years in now and I’m busier than I’ve ever been. I couldn't be happier.

YouTube It

To see and hear a sampling of Steve Lukather’s guitar mastery, check out the following clips.

Full-length concert of Toto live in Amsterdam. Luke gets a nice solo feature from 35:59–37:55.

Sharing the stage with guitar gods Steve Vai and Joe Satriani on the G3 tour, Luke belts out a soulful rendition of Hendrix’s “Little Wing,” and takes a rippin’ solo starting at 1:53.

Playing with fellow studio legend Larry Carlton, Luke tears it up on Jeff Beck’s legendary ballad “Cause We've Ended as Lovers.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)