Chops: Advanced Beginner

Theory: Beginner

Lesson Overview:

• Understand the basics of

working with a metronome.

• Learn a two-step process

for expanding your musical

vocabulary.

• Create more cohesive phrases

by repeating rhythmic motifs.

It amazes me how much incredible music has been and will be created using a pentatonic scale. You can get a ton of mileage out of just those five notes. Throw in a few variables like tone, technique, and rhythm and the musical possibilities are infinite.

Let’s focus on rhythm.

One of the things I love most about my favorite improvisers is their ability to develop musical ideas. I’m drawn to a solo when a player weaves through idea after idea, rather than playing a slew of random licks. Play fast, slow, high, low, legato, staccato … as long as you stick with one concept for a little while, you can give the listener’s ear something to latch on to and create an exciting solo with depth and direction.

If you’ve ever felt like you’re always playing the same thing, or you don’t know what to play next, one of the best remedies for getting out of this improvisational rut is to incorporate rhythmic motifs into your arsenal of tricks. Whether it’s Wes Montgomery’s epic performance of “No Blues” (from Smokin’ at the Half Note), where he stretches out on over twenty choruses of a blues, or Jimi Hendrix’s wailing guitar solo in the instrumental masterpiece, “Driving South,” these players are using rhythmic motifs left, right, and center. They are taking small rhythms, usually one or two measures long, and repeating them with various note choices. This approach is an awesome way to inspire new ideas and expand your musical vocabulary.

Let’s jump right in.

Step #1: Be able to effortlessly

execute strong rhythms using

a metronome.

In order to play any rhythm in a musical

way, on the fly, it’s essential to have the

technical facility to rock through a number

of exercises with the click. Remember, the

metronome never lies. Using one correctly

is a sure-fire way of tracking your improvement,

efficiently increasing your speed, and

knowing that you can deliver a guitar part

with precision. Listen to it more than to

yourself to ensure you’re playing in time.

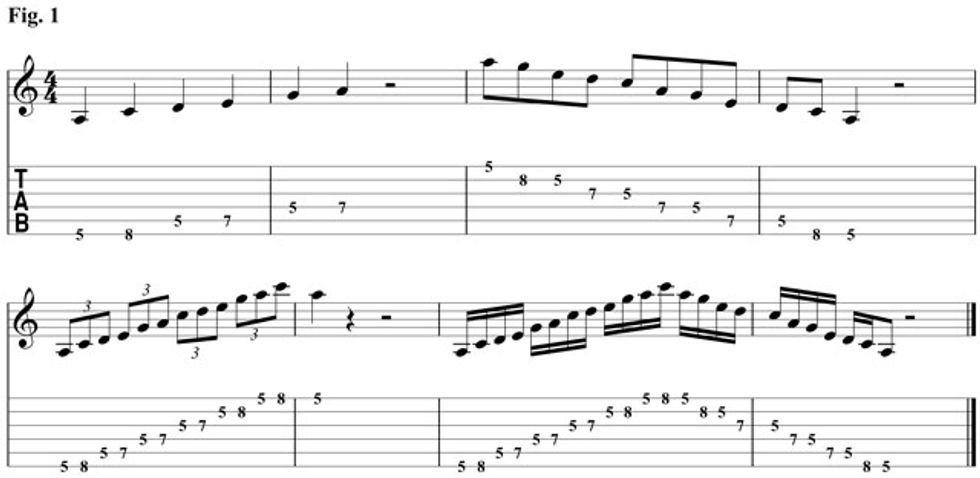

Here are a few examples of how I like to “woodshed” a scale. Let’s use an A minor pentatonic scale (A–C–D–E–G) as an example. Set your metronome to 80 bpm and work on playing the scale in quarternotes, eighth-notes, triplets, and 16thnotes. In Fig. 1 you can see an example of this. If the tempo is challenging, find a tempo that feels super comfortable to you. Keep practicing the exercise until you can play it perfectly, and then increase the click very gradually until you get to 80. If I’m struggling with a tempo, I like to use this approach, then surpass the desired tempo by a good five to 10 clicks so that when I go back to the original, it feels like a breeze.

I also like to play scales in all possible intervals within an octave—in this case, in intervals of fourths, fifths and sevenths. It’s a technical workout to say the least, and it forces you to visualize the notes in a different way. In Fig. 2 you can see how I take this scale first through fourths, then fifths, and finally sevenths.

Now it’s time for the fun part—this is where creativity takes over. Experiment with improvising each of these rhythms exclusively for an extended length of time. I find when you limit yourself to specific parameters, many more musical possibilities reveal themselves that you wouldn’t have otherwise discovered. Remember, the metronome is acting like your personal drummer, so keep it clicking!

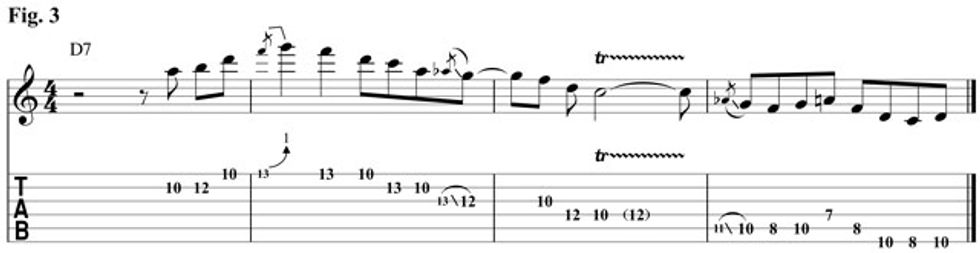

Next, let’s explore how to use the metronome to create different feels and further challenge your rhythmic sensibility. When most guitarists work with a metronome, they either think of it as a quarter-note pulse or on beats 1 and 3. Try setting your click to around 40 bpm and imagining it on beats 2 and 4. In Fig. 3 you can hear how this adds some extra swing to your phrasing. You’ll need to subdivide the bar to really get a feel for where the beats fall. Internalize this by jamming along with recordings and always be aware of where the downbeat is. Continue with this idea by shifting your perception of the click so that it falls only on beat 2, then 3, and finally beat 4.

Step #2: Create rhythmic motifs.

Now that you have the scale under your

fingers with rhythmic precision, it’s time to

jam out some motifs. Start off by making

up one- or two-bar rhythms and see if you

can weave the motif through the scale in a

musical way. Keep it going and stretch out

for several minutes, hours, or days! This is

such a great way to bring out new lines in

your playing.

In Fig. 4 I begin with a two-measure rhythm that I repeat in different areas of the neck throughout the example. Don’t be afraid to add bends, slides, and doublestops to keep things interesting. I move to a triplet-based pattern in Fig. 5 that works well over either an F chord or D minor. In performance, after a few repetitions, you can springboard off the idea to lead into your next phrase.

This approach to expanding your musical vocabulary is so practical because it leaves a lot of room for creativity—come up with a simple rhythm and then explore the vast possibilities of how to express the rhythm within familiar scales. The motifs will inspire new ideas and help to create thoughtful, dynamic solos.

Donna Grantis is a Toronto-based guitarist,

composer, musical director, and educator.

Her jazz-rock trio, the Donna Grantis Electric

Band, recently released their debut album,

Suites. As a session musician, she has

performed with award-winning artists and

tours internationally. For more information,

check out donnagrantis.com.

Donna Grantis is a Toronto-based guitarist,

composer, musical director, and educator.

Her jazz-rock trio, the Donna Grantis Electric

Band, recently released their debut album,

Suites. As a session musician, she has

performed with award-winning artists and

tours internationally. For more information,

check out donnagrantis.com.