Staying creative and phrasing musically while playing chords, especially over a blues progression, seems like an impossibility to many players. After all, most blues songs contain only three chords, the I, IV, and V. So how can you make those simple chords more interesting? The answer is by using chord substitution.

Substitution is when two chords share enough notes in common that by exchanging one for the other, the overall harmonic function remains unchanged, but the color and very often the melodic nature of the chords is enhanced. By adding extensions to standard dominant 7 chords found in a blues, you can see a whole new world of substitutions become available. No longer will you be stuck playing two or three shapes for an A7 chord, but rather you’ll be equipped with a massive palette of colorful chords that will catapult your blues playing to another dimension!

Dominate the Minor Subs

Most players are familiar with playing dominant 9 chords; they are, after all, very commonly used in many genres of music, especially the blues. The most common form of this chord can be found in the first measure of Ex. 1. This A9 chord contains the five notes of a dominant 9: 1– 3–5–b7–9 … or in terms of note names: A–C#–E–G–B.

The 9 in the A9 chord is considered an extension because it takes the foundation of the dominant 7 chord (1–3–5–b7) and “extends” it by an extra third, creating the 9. In measure 2 you can see that removing the root note (A) will leave you with a four-note chord: C#–E–G–B. This coincidentally is the exact spelling of a C#m7b5 chord. Yes, this means that within an A9 is a C#m7b5.

By removing the root note of an extended dominant chord you are left with a new chord that can easily be substituted in place of the original dominant 7. This means that in nearly every circumstance you can substitute a m7b5 chord for a dominant 7 because within the dominant 9 version of that chord lies the corresponding m7b5. In order to transpose this to any key, you simply build a m7b5 chord upon the 3 of the dominant 7, as seen in measures 3 and 4. C# is the third of A7 and so you can substitute a C#m7b5 for any A7 and it will retain the function of the A7.

Ex. 2 highlights this in the context of the first four measures of a blues in A. The first two measures are a standard A7 riff, however measures 3 and 4 utilize the m7b5 substitution. In this case the C#m7b5 is used to create harmonic and even melodic variety by sliding in and out of the chord from a half-step below. This is a common technique in jazz-blues playing.

Summary: Extending a dominant 7 to a dominant 9 creates a m7b5 chord built on the 3 of the dominant chord. Playing this m7b5 chord in place of the original dominant 7 is harmonically acceptable because it is implying the dominant 9 tonality, even without the root note being present.

Dominant 13 Chords

Following this concept of extending chords, a dominant 13 chord is another common variation of a dominant 7. Unlike piano players, guitarists don’t have the luxury of playing with all 10 fingers, so we must make exceptions. A fully extended dominant 13 chord would contain all seven notes of a key: 1–3–5–b7–9–11–13. Since we are limited in the number of notes we can realistically play, it’s important that we cut out unnecessary notes. It’s very common to cut out the 5, 11, and even the 9, leaving the chord spelled as: 1–3–b7–13.

In the beginning of Ex. 3 you can see a standard A7 chord voicing. There is only one note difference between this voicing and the A13 chord found in measure 2. Namely the E (5) located on the 2nd string. By removing this note and replacing it with an F# (13) we have essentially created an A13 chord.

If desired, playing the 9 as part of this A13 is always an option (A–C#–G–B–F#). In measure 3 you can see this A13 chord, but it is often cumbersome to play while including the bass note. Removing that root note will leave you with a b7–3–13–9 shape. Just as removing the root in an A9 chord left us with a C#m7b5, removing the root note of this A13 leaves us with a new four-note chord: Gmaj7#11. This may seem like a complicated way of saying “A13 with no root note,” but it goes to show you that the substitutions for a dominant 7 chord can be profound.

In Ex. 4 you can see the first six measures of an blues in A with the addition of a Gmaj7#11 in measures 3 and 4. Measure 5 introduces a D9 which is then substituted with an F#m7b5, recapping the first substitution we discussed (building a m7b5 upon the third of any dominant 7 chord).

Summary: Dominant 13 chords are most often played on guitar without the 5, 11 and occasionally the 9. However, swapping the 9 for the root creates: 3–b7–9–13. By making the b7 the new “root note” of this substitution chord you create a major7#11. An easy way to implement this into your everyday playing is by building a maj7#11 chord on the b7 of any dominant chord. In the case of an E7 you would substitute a Dmaj7#11 which would create the same harmonic function as an E13.

“Hendrix” Chord Subs

Just as the name implies, a dominant #9 chord is a dominant 7 chord, with a #9 extension. Commonly known as the “Hendrix” chord, this is a very useful extension for any dominant 7. The interesting thing about this chord is that the #9 is also the same tone as a b3. The reason for it being called a #9 is that in a dominant chord, there is already a 3, and it’s major! Since you can’t theoretically have both a 3 and a b3 in a chord, that b3 must be called a #9 instead (this is called enharmonic spelling).

Looking at Ex. 5 you can see an E9 which is spelled as E–G#–D–F#. Notice the conspicuous lack of a 5. This is very common in many chords because the 5 adds nothing harmonically to the chord. In measure 2 the F# is moved up a half-step to create an E7#9 chord. In measure 3 you can see another extension added to the E7#9; it would be the #5 added by barring the fourth finger across the top two strings at the 8th fret. This is another very common extension and one that creates a new substitution when the root note is removed.

The spelling of the E7#9#5 is: E–G#–D–F##–B#. Why B#? Well because it is a #5 it must be called B#. B is the fifth of E and a #5, according to enharmonic spelling, means that it must be called a B#.

Compare the chord shape in measure 4 to the chord shape of the Gmaj7#11 from the previous example. That’s right, it’s the exact same chord shape! This means that by playing an E7#9#5 and removing the root note, you are left with a G#maj7#11…I told you extensions can lead to profound new substitutions!

Ex. 6 outlines a typical blues turnaround. The standard turnaround being E7–D7–A7–E7, this version begins by using an E7#9 in place of an E7. This upper note then descends chromatically to form an E9 on beat four and then to a D7#9. Next is a standard blues walk-up which takes you to the E bass note at the beginning of measure four. However, the ending of measure 4 introduces the G#maj7#11 which is the substitution for an E7#9#5.

Summary: Adding a #9 to a dominant 7 chord creates the common “Hendrix” tonality that allows players more freedom to solo. However, barring the fourth finger across the top two strings creates another extension, the #5. This chord, E7#9#5, when played without a root note is spelled as G#–D–F##–B#. This spelling creates a G#maj7#11.

Dominant 7b9 Chords

One of the most versatile dominant chords imaginable is the dominant 7b9 chord. Just as the name suggests, it is nearly identical to a dominant 9 chord except in this case, the 9 is flatted by one half-step, hence the name “dominant 7b9”.

Looking at Ex. 7 you can see a D9 chord in measure 1 spelled out from 5th string to 1st as: D–F#–C–E–A. In measure 2 is a D7b9 chord spelled out as: D–F#–C–Eb–A. There is only one note difference between these two, but that b9 makes a huge difference in the function of this chord.

Moving on to measure 3, we remove the root note and end up with a F#dim7. Here is where things get really interesting. Diminished 7 chords are symmetrical, meaning they are comprised entirely of minor thirds. The notes of this F#dim7 chord are: F#–C–Eb–A. Now if you move this same chord shape up a minor third on the fretboard (three frets) you’ll get an Adim7 chord. The spelling for this chord is: A–Eb–F#–C. That’s right, it’s the exact same set of notes in another inversion. Move it up another minor third and you get Cdim7 and one more minor third will get you Ebdim7.

Essentially, all these diminished 7 chords can be considered a substitute for a D7b9 because they all share the same exact set of notes—minus the D root note. The implications of this are enormous because now the option to play diminished scales and chords can be easily superimposed on top of any dominant 7 chord.

A great way to conceptualize this while playing is to first become familiar with the chord shapes for diminished 7 chords so you can easily finger them in the midst of a song. Then simply look for any of the following four notes within a dominant 7 chord: 3–5–b7–b9 and build your diminished 7 chord on one of those tones. From there you are free to move that chord shape up and down in minor third intervals and you’ll retain that dominant 7b9 harmony the entire time.

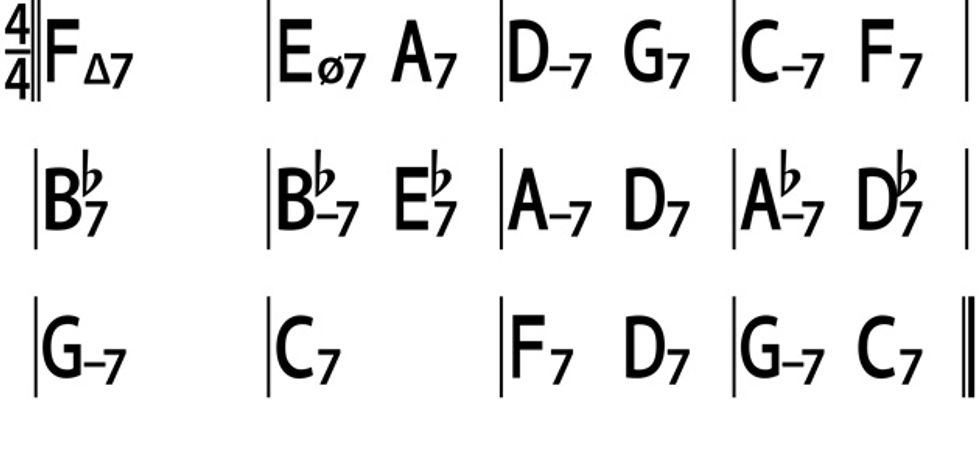

Look at Ex. 8 and you’ll see a full 12-bar blues progression in A that uses the sub techniques we’ve covered so far. I’ll point out a few things to take note of. In measure 6 the F#dim7 is moved up a minor third to Adim7 and then to Cdim7. These two measures are utilizing the harmonic function of a D7b9 without the root note.

Going into measure 8, the diminished 7 substitution is once again present, but this time it’s used in place of the A7 chord normally found in this measure. In place of an A7 we are substituting a C#dim7 followed by a Bbdim7 and a Gdim7. Remember this diminished 7 chord substitution works on the 3–5–b7–b9 of any dominant chord. In this case, these three diminished 7 chord substitutions are built on the 3, b9, and b7 of A7b9.

The final measure introduces another of the substitutions we’ve discussed, the maj7#11. In this case the Dmaj7#11 is substituted for the E7 that normally occurs in this bar. This Dmaj7#11 functions as the upper structure of an E13 chord, without the root note.

Summary: Dominant 7b9 chords are essentially equivalent to a diminished 7 chord. By removing the root note of a dominant 7b9 (1–3–5–b7–b9) chord you are left with a diminished 7 chord which is symmetrical and can be moved up or down in minor thirds. This diminished 7 chord can be built on the 3–5–b7–b9 of any dominant chord and will retain that dominant 7 function, albeit with much more tension and color.

Admittedly, there’s a lot of info here, so don’t feel like you need to hop on all of these ideas at once. Pick one, try it out, explore it, and maybe even write a tune with it. Only then will it become a part of your vocabulary. Good luck!