Beginner

Intermediate

- Increase your chord vocabulary.

- Transform basic barre chords into more sophisticated voicings.

- Explore the principles of chord substitution.

Have you ever felt like jazz is a secret society? An exclusive club where the password to enter is to spell out a Bb7#5b9 chord? Well, in this lesson we’ll start to decode the language of jazz harmony and get you playing standards in just a few minutes ... even if all you know are cowboy chords!

Reverse-Engineering Chords

One of the biggest obstacles guitarists face when starting to learn jazz standards is coming to terms with the abundance of new chord names and shapes favored by jazz musicians. One can randomly open The Real Book—the most commonly used jazz fake book, a resource you should have access to, and which I’ll frequently refer to throughout this lesson—and immediately be challenged by confusingly named chords. From the aforementioned Bb7#5b9 to those chords with the little circles in the upper right-hand corner, which sometimes have a slash through them, it can seem as if you’re reading a foreign language. These chords with longer names are variously known as “extended chords” and “altered chords.” The former means that they extend beyond both the common1–3–5 and the slightly more intricate 1–3–5–7 formulas by including the scale degrees 9, 11, or 13. The latter means they feature alterations, such as a b5, #5, b9, or #9. Thus, the first thing we need to do is reverse-engineer these chords to make sense of the names and shapes.

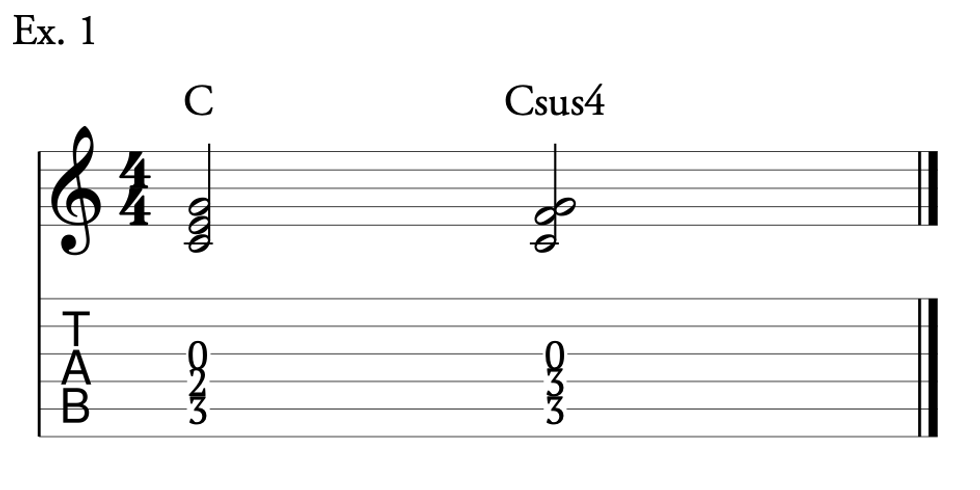

Let’s start by looking at a common chord pattern found in many jazz standards, including “Autumn Leaves,” “Take Five,” “Fly Me to the Moon,” and “My Favorite Things.” Each of these tunes is built around chords that move through the circle of fourths. This means that the root of each chord is separated by four scale degrees (Ex. 1).

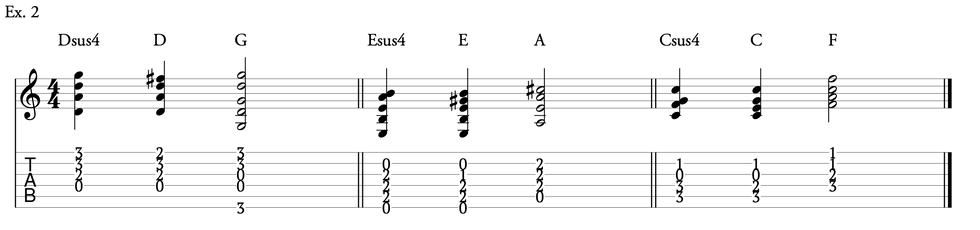

Now, if these chord names and shapes are new to you, it’s almost pardonable to give up by measure two. Right from the outset, both Am9 and D9 are challenging chords to play. And goodness knows how many times I’ve had to remind students what an F#m7b5 is. But instead of giving up, I recommend simplifying. And for you snobs out there, if you insist on calling this “dumbing it down,” so be it. At least we’re planning on evolving!

The most efficient way to simplify is to remove the numbers from the chords, including numbers in parentheses. And voilà—you get chords so easy even beginners can play jazz (Ex. 2). I need to point out one anomaly: How did an F#m7b5 become Am? Easy. The only difference between the two chords is the F# in the bass. In fact, if we were playing folk music, we might call this chord an Am/F#. Now, in different keys, this substitution of a basic minor triad for m7b5 chord is not always so obvious, but with a little practice you should be able to figure out the alternatives: For instance if Am (A–C–E) substitutes for F#m7b5 (F#–A–C–E), then Bm (B–D–F#) can sub for G#m7b5 (G#–B–D–F#).

Color Your Chords ... or at Least Barre Them!

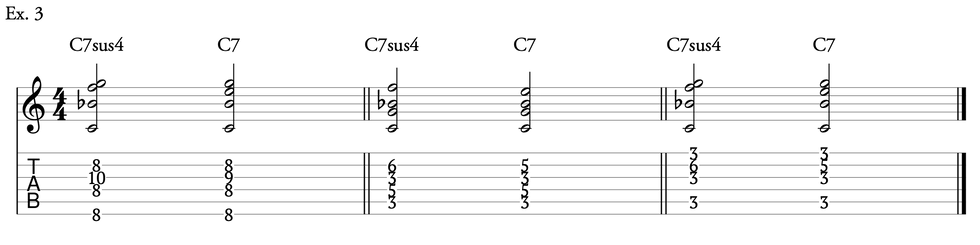

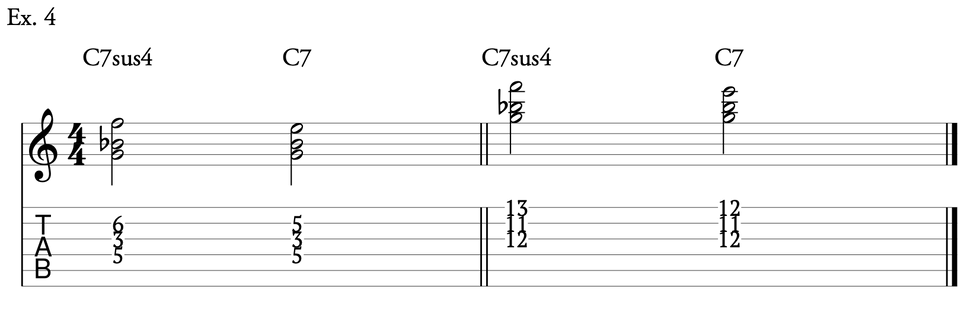

From here you can start doing one of two things: You can either add some color, via extensions, to your chords by removing or adding a finger to these basic shapes, as shown in Ex. 3. At the risk of oversimplifying, it doesn’t make much difference if you add a 7, 9, or 13 to the chord. The other option is to play them as barre chords like Ex. 4. Either way, you’ll start to build a more refined chord vocabulary.

Rules for Simplifying

Before we move on, a few basic rules to remember for simplifying chords:

- You can remove numbers from any chord. The only exception is the m7(b5) chord (see above).

- You cannot remove sharps or flats directly after the initial chord letter name. Bb13 can only become Bb, not B.

- You cannot remove minors. Gm9 can become Gm, but not G.

- You can remove any alterations such as b5, #5, b9, or #9.

- You can drop all notes after slashes. A7/G can become A7 or A.

When in Doubt, Transpose

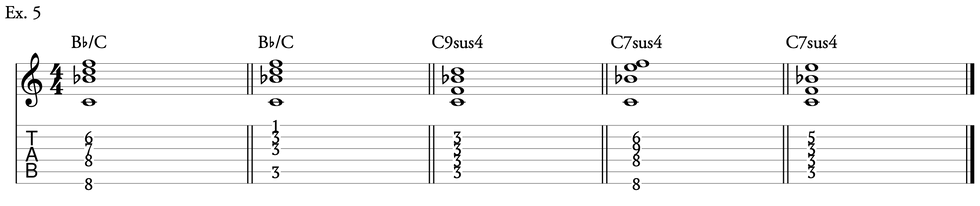

Another problem with jazz is that, for a beginner, it can be difficult to identify an easy chord progression, like Ex. 1, from a more complex one, simply because of the key it is written in. For example, a song like Charlie Parker’s “Donna Lee” in what I call an unfriendly guitar key, such as Eb or Ab, might at first glance seem convoluted because of all the flat chords (Ex. 5). But if you were to transpose that song into a friendly guitar key, such as D or G, the progression would become much more transparent (Ex. 6).

Modulation

There is one more issue we need to address: jazz songs that modulate, or shift, through several different keys. This occurs in such tunes as “How High the Moon,” “Cherokee,” and “Giant Steps,” and makes the simplification process problematic because we lose many of our open-string chords and therefore have to rely more on barre chords. But I have to be frank with you here, if you’ve gotten this far into jazz, playing more urbane songs, such as those I just mentioned, you’re probably best off learning the chords The Real Book uses. The simplification processes used in this lesson will work for these more complex songs, but eventually you will want to learn the names and shapes of more sophisticated chords. Thankfully, you can ease into those as well. I suggest first working out of the barre chords shapes, where you can make maj7, m7, and dom7 chords relatively easily by lifting off, or moving around, one or two fingers.

In Ex. 7, we have basic barre chords transforming into jazzier 7th chords—in the guitar-friendly key of C. Ex. 8 demonstrates the same process in the key of Eb, which is already becoming friendlier. Once you’re familiar with these chord names and shapes, the possibilities for alternatives become practically endless (though not always practical).

Oversimplified?

Even though I believe I’ve made this process relatively simple, it will probably take intermediate players a few passes to make these changes with ease. And you’ll want to make these changes on paper, as well as in your head. So don’t hesitate to write out your simplified progressions. Not only will this make the whole process easier, it will reinforce the material.

One last—and vital—piece of advice: Learn to sing some jazz standards. There are many great versions of jazz standards performed in non-jazz idioms: “Summer Time” by the Zombies, “Autumn Leaves” by Eva Cassidy, and “Ain’t Misbehavin’” by Hank Williams Jr. are excellent examples of simplified versions of the originals. Another benefit to singing is that many of the melodies to jazz tunes that seem obtuse when played instrumentally become stunningly lucid when they’re attached to the words their composers originally intended. Heck, when you hear Ella Fitzgerald sing it, even “All the Things You Are” isn’t so odd.