Beginner

Intermediate

- Explore genre-defining elements of spy guitar.

- Learn how to use these elements to create your own spy guitar sounds and songs.

- Discover how musical intuition and music theory can work together to create mystery and suspense.

Although many might suspect that the sound of spy guitar begins in 1962 with the “James Bond Theme,” one must in fact go back to 1958 and Henry Mancini’s equally iconic theme for Peter Gunn.

While “Peter Gunn” begins with a jazzy drum groove, it’s the ominous, half-step-infused guitar riff that dominates the track. On top of the riff, the horns play a melody that contains a sinister b5 movement, half-step grace notes, and ends on an unexpected major 7 leading to tonal ambiguity. Ex. 1 highlights the aforementioned, genre-defining elements—out of context. Ex. 2 puts them all together in a “Peter Gunn” homage.

James Bond

With the Mancini precedent duly noted, we can move forward to perhaps the most quintessential of the spy guitar themes. Unfortunately, the original theme music is bedeviled by a messy composer credit that has been battled over for years between Monty Norman and John Barry. Regardless of its origins, it was John Barry who went on to compose countless themes and variations for Bond movies over the years and it is Barry I’ll imitate in this lesson. Like Ex. 1, the next few examples in our lesson isolate the Bond melodic and harmonic archetypes.

Ex. 3 is commonly known as a CESH or Chromatic Enhancement of Static Harmony, in which the basic tonality of the chord (in this case, first Em and then Am) stays static while an internal melodic line ascends or descends chromatically.

Ex. 4 features simple melodic motifs that use descending half-steps at the end of each one-measure phrase to create tension and suspense.

And Ex. 5 is a bass-string riff featuring syncopated 16th-notes that descend chromatically.

Ex. 6 combines the aforementioned elements together for a James Bond tribute.

Mission Possible: Odd Meters

Quite frankly, most of the melodic and harmonic concepts found in the spy guitar genre were pioneered by Mancini and Barry, with future composers adding only slight variations. Nevertheless, one of the most notable alterations was Lalo Schifrin’s odd-meter riff in the theme from Mission: Impossible. Schifrin’s 5/4 groove provides an off-kilter feel, adding to the cloak-and-dagger uncertainty created by the previously mentioned chromatics, b5 intervals, harmonic ambiguity, and slippery grace notes. As well as incorporating most of the melodic ideas we’ve already discussed, Ex. 7 highlights the odd meter.

I Spy with My Little …

Ex. 8 is another instance of the myriad derivations built from Mancini and Barry’s music. This time it’s Earle Hagen’s work on “I Spy,” written for the TV program of the same title. Here we’re in 3/4, and, for the first time in this lesson, we have a chord progression—Cm to Abm, rather than a static riff—that ends on the chord you’ve been waiting for ... a Cm(maj7).

Contemporary Spies

I couldn’t resist adding a slightly more contemporary piece to this lesson (just change the drums from jazz to something funkier, electronic, or more rock). Thus, Ex. 9 features all-purpose, suspense-building melodic intensity (half-step movement abounds) in B Phrygian (B–C–D–E–F#–G–A), perfect for all your cliff-hanger exigencies. You can practically hear the safe click at the end.

Spy Scales?

Up to this point I have specifically avoided mentioning any scales used in the creation of these compositions. This is because the theory behind the so-called “exotic scales” can be needlessly complicated. Essentially, I composed all of the examples using the natural minor scale, aka the Aeolian mode, with a few chromatic notes added for extra tension. Still, I feel duty bound to mention two additional scales, the harmonic minor and double harmonic minor (which is sometimes identified as the Hungarian or Gypsy minor).

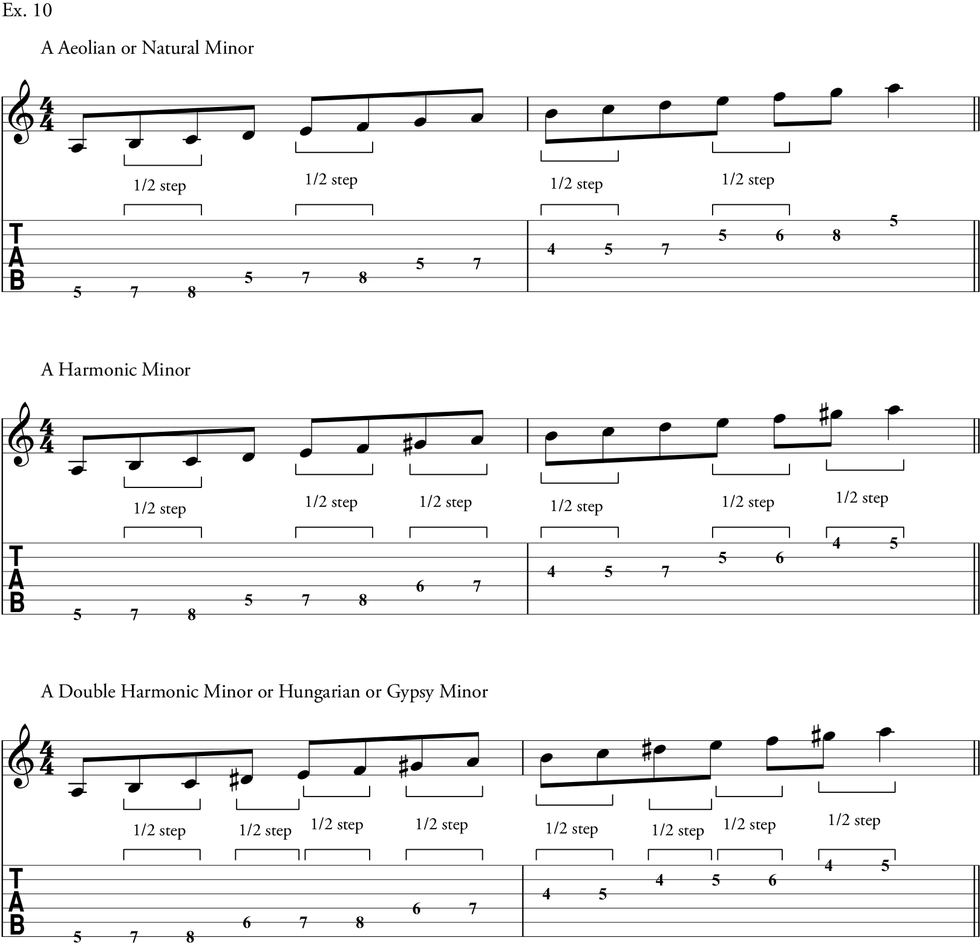

Ex. 10 shows these three scales (in two octaves) in succession, demonstrating how each is built off the previous one. Harmonic minor is the natural minor with a major 7, and double harmonic minor is the harmonic minor with a #4. See? Needlessly complicated.

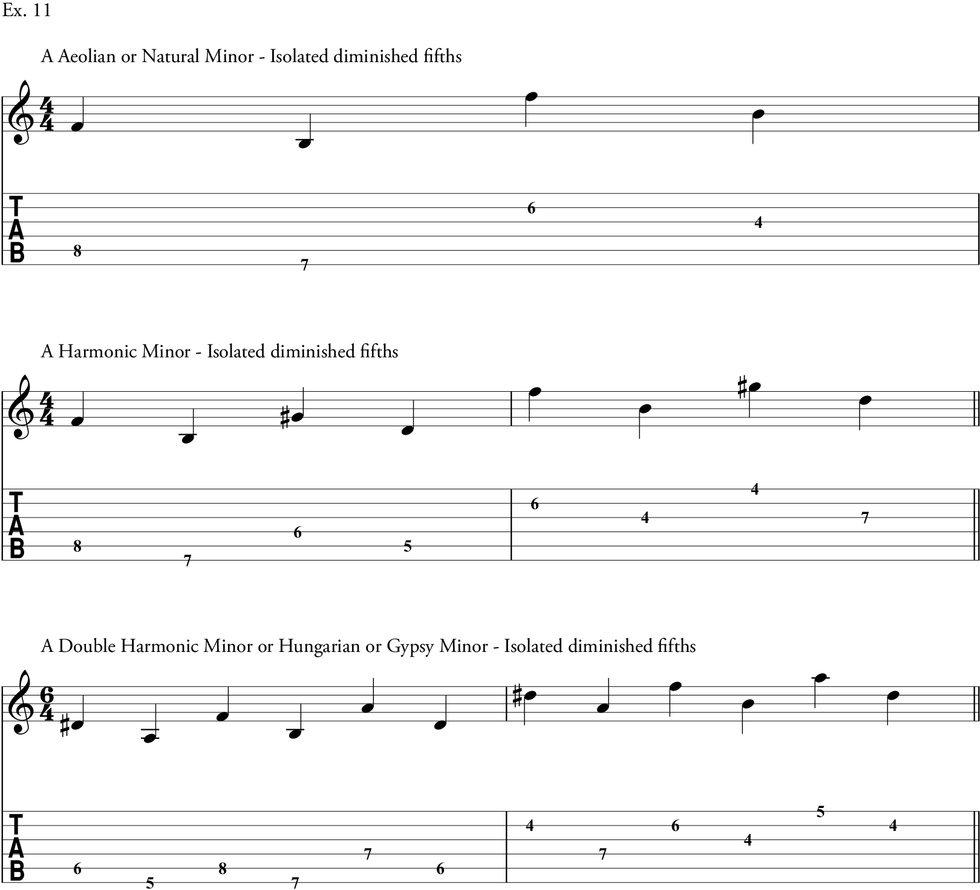

So ignore the theory and simply exploit the half-steps—labeled in Ex. 10—and isolated diminished fifths in Ex. 11. Natural minor has one and two respectively, harmonic minor has two and three, and double harmonic minor three and four. Just make sure they’re shaken, not stirred.

This lesson will self-destruct in 5… 4… 3… 2…