Some architects work in landscape. Others in interior or urban design. But Buddy Miller explores the architecture of sound, creating aural sculpture that is both supportive and, like I.M. Pei’s buildings, transporting. Although he learned to play in New Jersey—wound up by folk, country, and the Beatles—Miller made his bones in Austin, New York City, Los Angeles, and, ultimately, Nashville, where he is one of the city’s most respected guitarists and producers.

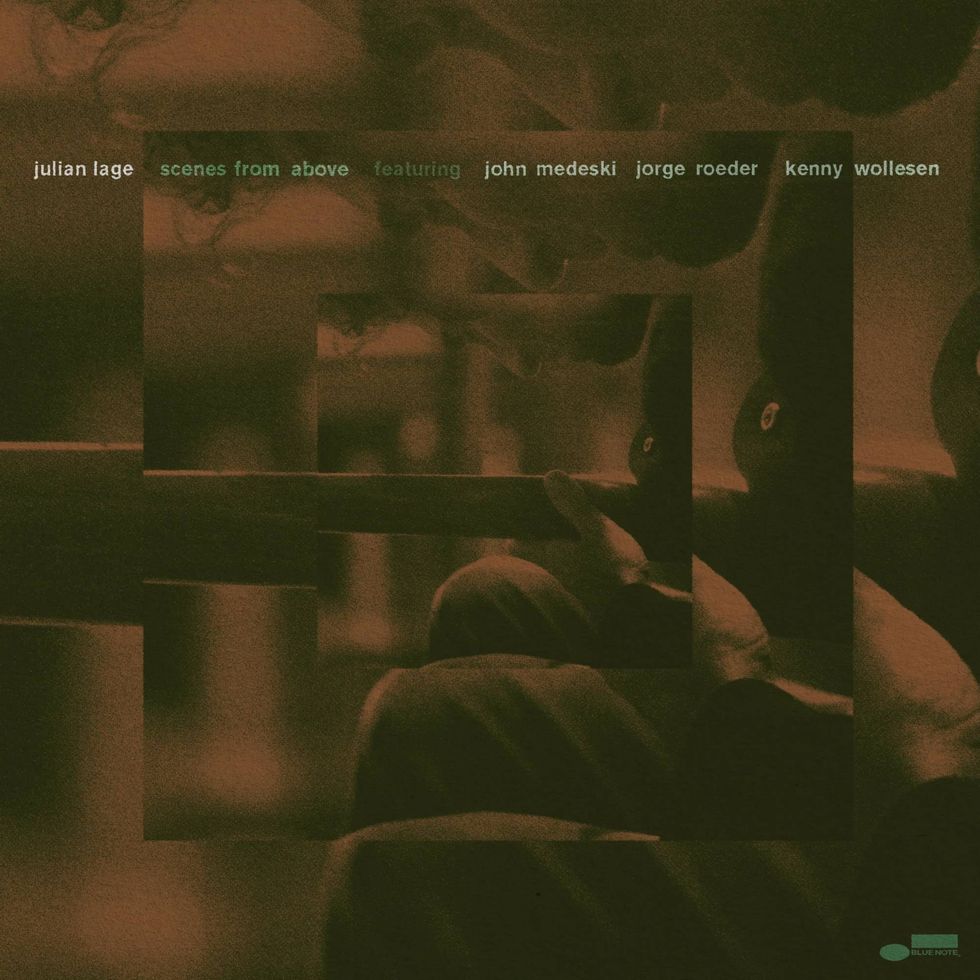

That’s not just because he’s got 13 Americana Music Awards and a Grammy, or ’cause he’s toured, recorded with, or produced that pluralistic roots genre’s royalty, including Emmylou Harris, Robert Plant and Alison Krauss, Steve Cropper, Solomon Burke, Allison Moorer, Patty Griffin, Shawn Colvin, Richard Thomopson, Jimmie Dale Gilmour, his good friend Jim Lauderdale, Lucinda Williams, Elvis Costello, Levon Helm, John Fogerty, Richard Thompson, and the beat goes on. It’s not even because he’s been the leader of the all-star house band for the Americana Music Association’s awards ceremony since 2005, or written, alone and with his wife Julie, a stack of songs that speak frankly from the heart and have been covered by tradition-grounded artists as well as Little Jimmy Scott and Jars of Clay.

The thing is, Miller’s just so damn good. His playing is rooted yet unbound. He likes nothing more than the sound of two amps—their tremolo units clashing in time, their reverb tanks set widely apart—pumping out the big tone he gets from his vintage Wandre guitars. And lest you think, given that he started his career playing country, that his sound is all twang and drang, he’s also at home with the finest improvisers. Ask his pals Bill Frisell and Marc Ribot, with whom he recorded and released the free-ranging guitar exploration Majestic Silver Strings, abetted by Greg Leisz, in 2011. And yeah, he’s also got a warm, honest voice that’s been especially affecting on the four albums he’s released with Julie Miller, who, in earlier decades, was his frequent onstage spark plug.

In The Throes

Provided to YouTube by Redeye WorldwideIn The Throes · Buddy & Julie MillerIn The Throes℗ 2023 New West Records, LLCReleased on: 2023-06-28Main Artist: Budd...If there’s any sound that resonates through Buddy and Julie’s latest, the just-released In the Throes, it’s love. Not the Hallmark-romance type, but the real thing, messy and brutal and honest and, ultimately, affirming and enduring. And weird. Check out “I Been Around,” which has low and high guitar lines wandering through the arrangement, pacing, nearly lost with angular nervousness, around Julie’s powerfully throaty vocal performance. It‘s about the roller-coaster ride of a life shared, and sounds like a refugee from a Tom Waits album—or maybe a corpulent bear on a honey-rush staggering through a forest. Or, to borrow a description from the late Jim Dickinson, “like a drunken circus parade walking down the street.” And that’s a good thing.

“Everything is borrowed from your influences, and I’ve grown to appreciate them so much more.”—Buddy Miller

“That one almost got thrown out,” says Miller, as we talk in a room adjacent to his home studio—the same space where Richard Thompson cut breakneck solos while watching birds through the window during the recording of Thompson’s 2012 album, Electric. “I had a session that had just ended, and Julie woke up and just stumbled downstairs the way she does and said, ‘Pick up a guitar, play this,’ and we messed it up, messed it up, messed it up, and finally got it, and then she started singing, so it was just really raw, rough—things were distorted so I made them more so. She only sang it once as we recorded, and then she wandered outside and I overdubbed stuff on it, and that was it. We couldn't even figure out what some of the lyrics were, so we took a guess, because I was playing along with her pretty loud in the room. It was hilarious. We would just listen to it and laugh and dig it, and when I said, ‘This needs to go on the record,’ she was like, ‘I don’t think so.’”

This is what happens when two creative musicians who love each other work together: occasional, unpredictable, instant magic. And small disagreements. So, like all 12 of the songs on In the Throes, which are driven by Julie’s lyrics, “I Been Around” is essentially a demo recording conflated into a polished, but not too polished, song. “It’s the first album I did where I thought … well, we’ve got these songs, and they sound good already, and while I love playing with musicians, I decided to use the guitar and vocals I had, and set up bass and drums and keys, and overdubbed.”

That’s why In the Throes is as close as you can come to hearing the Millers’ raw, since Julie—who has severe fibromyalgia—no longer performs live. But even raw, Buddy and Julie’s music has grace and character. The opening “You’re My Thrill,” about finding solace in a partner, is reverb-warmed ascendance—touching in its elegance and devotion. Julie is a rare vocalist, with a sweet-toned voice that’s all innocence and experience, both girlish and world-wise. And Buddy … well … if he isn’t the ultimate accompanist, he’s certainly close. That echoes in every cut of In the Throes, whether they’re singing the original hymn “The Last Bridge You Will Cross” together or Buddy is channeling ’60s British rock and classic country while Julie lays down her straight truth on “The Painkillers Ain’t Workin’.”

Buddy attributes his songwriting abilities to Julie’s inspiration and ass-kicking, and considers her the mightier writer. Julie, in turn, says, “I guess I did get him to write his first song, and now he’s so much more talented than I am. But we started out together a long time ago, and we’ve ended up being really inside each other when he accompanies me. It really means a lot. I gave him a hard time in the past. Sometimes he just kind of played songs like a typical country player. I said, ‘You’ve got to listen to the intricacies of the lyrics and what’s going on inside them.’ I rebuked him,” she says, chuckling, “and he really came along.”

“As far as finding my voice,” says Buddy, “I always thought I had my voice, but as I get older I realize that I’m just finding my voice now. Everything is borrowed from your influences, and I’ve grown to appreciate them so much more.”

“I rebuked him, and he really came along.”—Julie Miller

Miller picked up the guitar in ’61 or ’62, he thinks, inspired by Joan Baez’s debut album. But after the Beatles broke, he had a steady diet of rock, folk, and country as he grew into the instrument. As a kid in Princeton, New Jersey, he took group lessons from folk musician Peggy Seeger (“she had that right-hand, Carter scratch down”), and soon fell for the sounds of James Burton, Jerry Garcia, and Jorma Kaukonen. “They had a freedom that just made everything else seem possible,” he observes.

Miller’s first quality guitar was a Gibson J-160E. “I loved the Beatles and everything else at the same time, and I agonized over what to get,” he says. “I wanted an electric and I wanted an acoustic, and I saw them playing a J-160E in A Hard Day’s Night. I didn't realize that they weren't really playing it on the screen, and it all sounded so good, so that's what I thought I wanted. It was the worst guitar for me. I'd play with my little friends in the garage, with a Silvertone amp, and it would feed back almost immediately when you'd turn it up, so it was useless. And with my friends that liked old-timey acoustic music, you couldn’t hear it because Gibson made the top a lot thicker than their standard models, so I was sort of pissed at the Beatles and had this guitar for a while until I could upgrade. I don't remember what I went to next. It probably wasn't an acoustic.” [chuckles.]

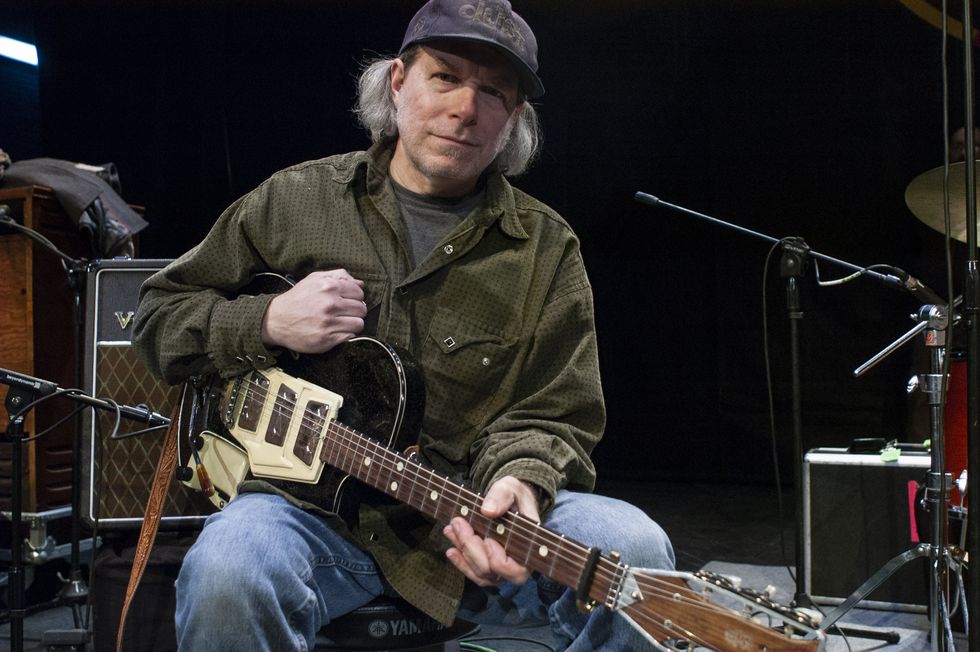

Buddy and Julie Miller on the couch in a room that’s a central live recording space in Buddy’s home studio. With the installation of a kitchen station, it was recently partially restored to civilian use. Nonetheless, guitars and other stringed instruments still line its walls.

Photo by Jeff Fasano

At 17, Miller joined a working band based in upstate New York. “We got our own school bus and drove across the country for the promise of a record deal, which never happened, and ended up playing on the steps of Berkeley to make enough gas money to get home,” he recounts. Later in the ’70s, he was in country-rock band the Desperate Men, who hit New York and northern New Jersey clubs hard. Buddy had also fallen under the spell of exceptional, modern country songwriters like Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt. So, in ’75, he moved to Austin.

“Traveling and going where music is wasn’t anything new to me by the time the Austin scene was raising its head,” Miller continues. “I was reading about it in, like, Country Music magazine, cause there was no way to find out about scenes other than a little bit of word of mouth. A few of the records that were cool at the time were made in Austin, and I’d just heard about the scene. I heard about Willie’s Picnic. I thought, ‘These are my people,’ and moved down there, and didn’t know anybody. The first gig I got was playing guitar for Ray Campi.”

“We got our own school bus and drove across the country for the promise of a record deal, which never happened, and ended up playing on the steps of Berkeley to make enough gas money to get home.”—Buddy Miller

Campi was an old-school Texas rockabilly stalwart, whose band was a training ground for younger musicians, including X’s Billy Zoom. Miller’s next stop was Partners in Crime, where he met vocalist Julie Griffin. They played bars and roadhouses, large and small, for the next few years. “Being in Austin was going to school,” he says. “There were so many great players and songwriters to watch and learn from. But after living there for a while, I realized they weren’t really making a lot of records in Austin at the time, and I wanted to make records.”

Near the end of the ’70s, Miller and Griffin started thinking about New York City—and especially the scene that was flourishing around the Big Apple’s then-preeminent roots room, the Lone Star Cafe—a thin slice of a storefront at the corner of 5th and 13th in Manhattan. “I wore the woman who did the booking there out, and she finally gave us a gig opening for Delbert McClinton,” Miller recounts. “That was one of the best gigs, and afterwards, we realized we should move up there.” So, on January 1, 1980, the night after playing a New Year’s Eve gig that covered their gas money, they left Austin.

Buddy Miller's Gear

Here’s a close-up look at Buddy’s first Wandre. Besides the sparkle finish, obvious body cracks, electrical tape, and rust are all part of its heavily played appearance.

Photo by Ted DrozdowskiGuitars

- Two vintage Wandre electrics

- 1954 Gibson J-45

- Jerry Jones baritone

- TEO mando guitar

- Phantom Mando Guitar

Amps

- Swart AST Pro

- Fender Deluxe Reverb

Effects

- Strymon El Capistan

- Fulltone Supa-Trem2

- Analog Man King of Tone

- Dunham Electronics Sex Drive

- Boss VB-2W Vibrato

- Boss TU-3W Chromatic Tuner

- Boss TU-2 Chromatic Tuner

Strings and Picks

- D’Addario XYXL (.010–.046; electric)

- D’Addario Nickel Bronze (.012–.056; acoustic)

- D’Addario Baritone sets

Buddy and Julie and their band became Lone Star regulars, as did Jim Lauderdale, who had moved to New York from Nashville in 1980. The budding country artist was working as a messenger for Rolling Stone magazine by day and, like Buddy and Julie, singing anywhere that would have him at night. By the end of the decade, the Millers, now married, moved to Los Angeles after Julie got a deal with a gospel label. With its huge studio scene, Los Angeles seemed fertile with possibilities. At nearly the same time, Lauderale also went there to cut his debut album, and stayed for a while, rekindling a partnership with Miller that continues today. In addition to occasional gigs and recordings together, for the past 11 years they’ve co-hosted The Buddy & Jim Radio Show on Sirius/XM.

The first sessions for Julie‘s gospel deal were fruitless. “She didn’t really like the producer and studio musicians, and would tell the musicians things they didn’t want to hear,” says Buddy. So the label suggested Julie and Buddy take the remaining money earmarked for her album and buy a 2-inch tape machine. “I loved to record, and they’d signed her based on her demos with me, anyway,” Miller says. “I’d been recording since my grandfather got me a battery-powered reel-to-reel with a mic on it, and then I got a Fostex 8-track and a TEAC quarter-inch 4-track, and then a Portastudio. So we got the 2-inch machine and a couple mic preamps. I really have to thank them for getting me a professional setup!”

Buddy and Julie’s apartment became Buddy’s first home studio. “Our whole place was smaller than the room we’re sitting in,” he says. “There was a bedroom, a little closet that opened up—and that's where I sat, inside the closet with a little tiny mixer. We got a Studer A80—a 2-inch, 24-track that didn't come with a remote. I had to have a guy make a remote, and it was horrible. You would press the button on it—it was spring loaded—and the button would fly across the room, but we eventually moved to Nashville with that machine.

“I keep all these colors around so that when I hear a song I can picture how the music should frame it, and I work from there.”—Buddy Miller

“The only reason we moved to Nashville is because we literally went bankrupt in L.A.,” Buddy explains, “and I’d been coming to Nashville every six months with Lauderdale, when he'd showcase for a new label deal. I realized houses were affordable here. Julie’s gospel deal was still sort of active, although we knew they were dumping her, so we kind of parlayed that into finding a loan for a house we could afford. And I adopted the mindset of taking everything that came along, because we were really broke, but everything that came along after a really early point here in Nashville was incredible. It was just beautiful music, so I soon changed my line to ‘I don't take anything that I don't love … and I love everything.’ I got to work on some incredible projects.”

Through the ’90s, Buddy produced and played on solo albums for himself and Julie, shepherded their work together, and produced Greg Trooper and Emmylou Harris. But in the 2000s, things really ignited. He produced albums for Jimmie Dale Gilmore, Solomon Burke, Allison Moorer, Patty Griffin, Robert Plant, the cast of TV’s Nashville (where he served as music director), the Wood Brothers, Shawn Colvin, and others—even a track for Christina Aguilera’s three-show stint on Nashville.

Over the course of all that, Buddy’s playing evolved to the point where he‘s both a deadeye messenger for songs and an imaginative texturalist with a broad sonic palette. His playing is instantly recognizable everywhere from Emmylou Harris’ live Spyboy to Lucinda Williams’ Car Wheels on a Gravel Road to Robert Plant’s Band of Joy to the War and Treaty’s 2018 breakthrough, Healing Tide. Sometimes it comes in shuddering, tremolo-driven waves. At others, it’s an ambient swell expressing a tide of emotions. And when it’s called for, he delivers raw rock and country lead guitar, with trim virtuosity.

“I feel that I've gotten way simpler,” Buddy offers. “I used to play as fast and as much as I could—and I thought I was really doing something, and it was fun but I don't think it did anything but, you know, maybe impress a few guitar players here and there. Supporting the song slowly became more of the thing for me, especially when I started songwriting, and found that a note or two can bring out the emotion of what's happening with a song.” He also cites Daniel Lanois, who worked with Emmylou Harris as a producer and studio player before Buddy joined her Spyboy band, as an inspiration for his ambient work, along with Frisell.

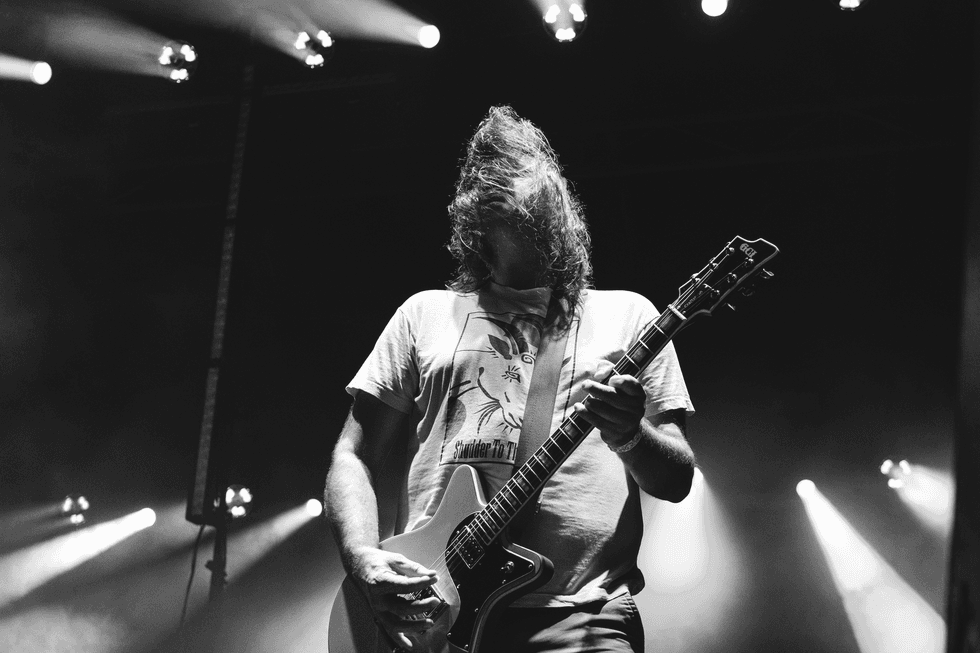

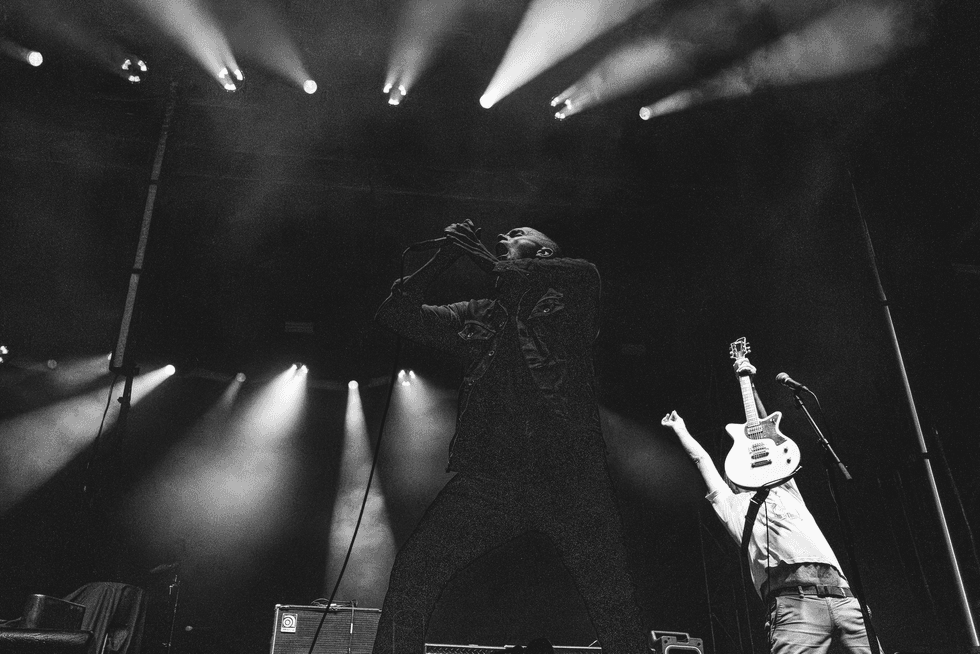

Buddy onstage with his black Wandre, which seems to have withstood the test of time and miles with less damage than his cream-sparkle model.

Photo by Jordi Vidal

To get the sounds he wants on short notice, Miller keeps his amp and pedalboard set up in his recording space, and the adjacent rooms have various stringed instruments—guitars, basses, autoharps, mandolins, mando guitars, baritones, and even a Gryphon Veillette—hanging on the walls, lining floors, and living in closets. “I keep all these colors around so that when I hear a song I can picture how the music should frame it, and I work from there,” he says.

His main electric guitars remain two Wandres—a black model and another in a cream-sparkle finish. The semi-obscure brand of Italian guitars were produced from 1957 to 1968, and Miller’s adoption has almost single-handedly made them collectible. Drawn to its finish, Buddy got the cream-sparkle guitar first, at a Colorado pawnshop, for $50. On these guitars, the neck is aluminum under the fretboard, and the metal plank continues back to the tremolo bridge, with the single-coil pickups mounted onto it. They never make contact with the body. But as anyone who’s heard Miller’s work knows, these instruments sound rich, deep, and full. They have push-buttons for pickup settings, and non-OEM strips of electrical tape holding the cream guitar’s plastic body together. The neck pickup on the cream model is backwards and wired out of phase. At one point, when Miller lived in New York City, this guitar was stolen. Somebody then found it under a truck, in its case, and returned it to Miller. “The person who stole this thing threw it out,” Buddy says, laughing. “They were hoping for something better.”

Another key to his sound is playing through two amps. During our 2019 Rig Rundown, Buddy was playing through two Swart AST Pro amps in parallel, with Universal Audio Ox Amp Top Boxes perched on both. Now, he’s down to one Swart and a Fender for its companion—usually something like a Deluxe or a Twin. Surprisingly, his inspiration for doubling up amps was Lou Reed. “I heard an interview with him on radio when I was, probably, 15,” Buddy relates. “He was talking about how he loved going to Manny’s [a famed instrument shop on New York City’s now-gone West 48th Street music row] and hooking up two Twins and turning the tremolos so they were working against each other. That stuck with me, and I love tremolo. It can cover up a multitude of sins, and it sounds great.”

These days, his pedalboard is practical and trim: a Strymon El Capistan, a Fulltone Supa-Trem2, an Analog Man King of Tone, a Dunham Electronics Sex Drive, a Boss VB-2W Vibrato, and two tuners—a Boss TU-3W Chromatic Tuner for electric, and an older TU-2 for acoustic instruments. That’s delay, tremolo, vibrato, and two flavors of crunch—a well-rounded sonic feast good for exploring inner and outer space.

“I love tremolo. It can cover up a multitude of sins, and it sounds great.”—Buddy Miller

When you see Buddy play, you’ll notice he often uses a pick, but will switch to his fingers when inclined. He’s been practicing both approaches since he was a youngster, thanks to the influence of Joan Baez and the Beatles. “I love the sound of fingers on strings,” he says. “Whether it’s acoustic or electric, it’s so warm. I also love old strings, so I let ’em go a long time. I only change them when there’s a big gig, because I don’t wanna break them onstage.”

For a typical gig, he’ll bring the Wandres, a Jerry Jones baritone, a mando guitar, and his early ’50s Gibson J-45. And if he’s accompanying a female singer, like Emmylou Harris, he’ll tune a guitar down a half-step, “so I can find my dots, because they’re often in the flat keys,” he says.

“I learned a lot playing with female singers, like Emmylou and Patty Griffin,” he explains. “Emmylou and I did a lot of touring—just the two of us—and that’s where I learned to just play simply, not be flowery. I don’t need to make my own statement. I support that voice, and it just happens to be one of the most beautiful voices in the world. That’s when I really took the baritone more seriously, as I can cover the low end and get some melodic stuff going on in the high end. I tended to play that with her, or a little mando guitar … but not much standard-tuned guitar, because she’d be playing guitar. So with the baritone I could fill out our overall sound more while keeping out of the way of that voice.

“I just try to respect the music and try to be simple, and I guess that’s kind of how I try to live my life, too,” says Buddy. “I try to respect everybody, and my playing should honor everything musical. When I’m playing with artists at the Americana Awards, whether it’s Emmylou or Steve Earle, I really want to honor them and their songs. I don’t want to show off my licks. It’s not about me. It’s about the group effort, the collaboration, the song in the moment. And I love getting lost in that moment. That’s the grateful ‘death’ for me—when the music completely takes over. It could be horrible or it could be beautiful, and either one is great.”

YOUTUBE IT

Buddy Miller walks the line between rock and ambient guitar playing live with Emmylou Harris, navigating the waters of “Deeper Well,” a song she wrote with Daniel Lanois and the late David Olney.

YouTube Search Term: Emmylou Harris - Deeper Well.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)