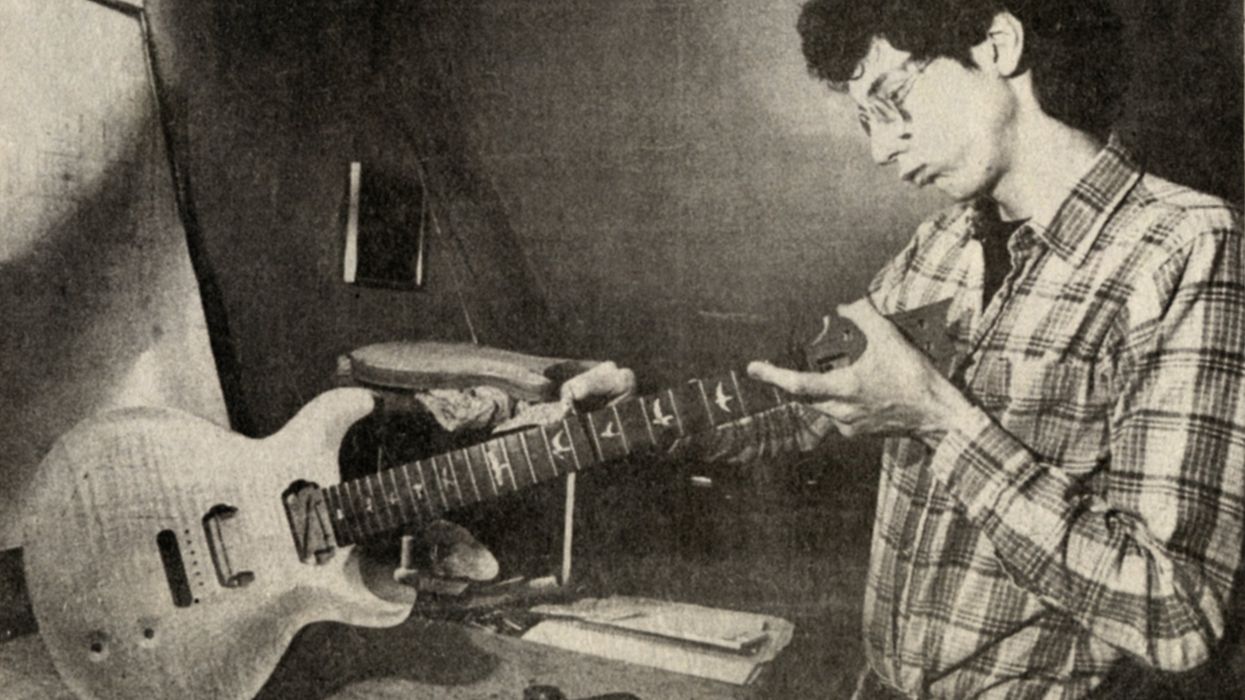

I love to learn, and I don’t enjoy history kicking my ass. In other words, if my instrument-making predecessors—Ted McCarty, Leo Fender, Christian Martin, John Heiss, Antonio de Torres, G.B. Guadagnini, and Antonio Stradivari, to name a few—made an instrument that took my breath away when I played it, and it sounded better than what I had made, I wanted to know not just what they had done, but what they understood that I didn’t understand yet. And because it was clear to me that these masters understood some things that I didn’t, I would go down rabbit holes.

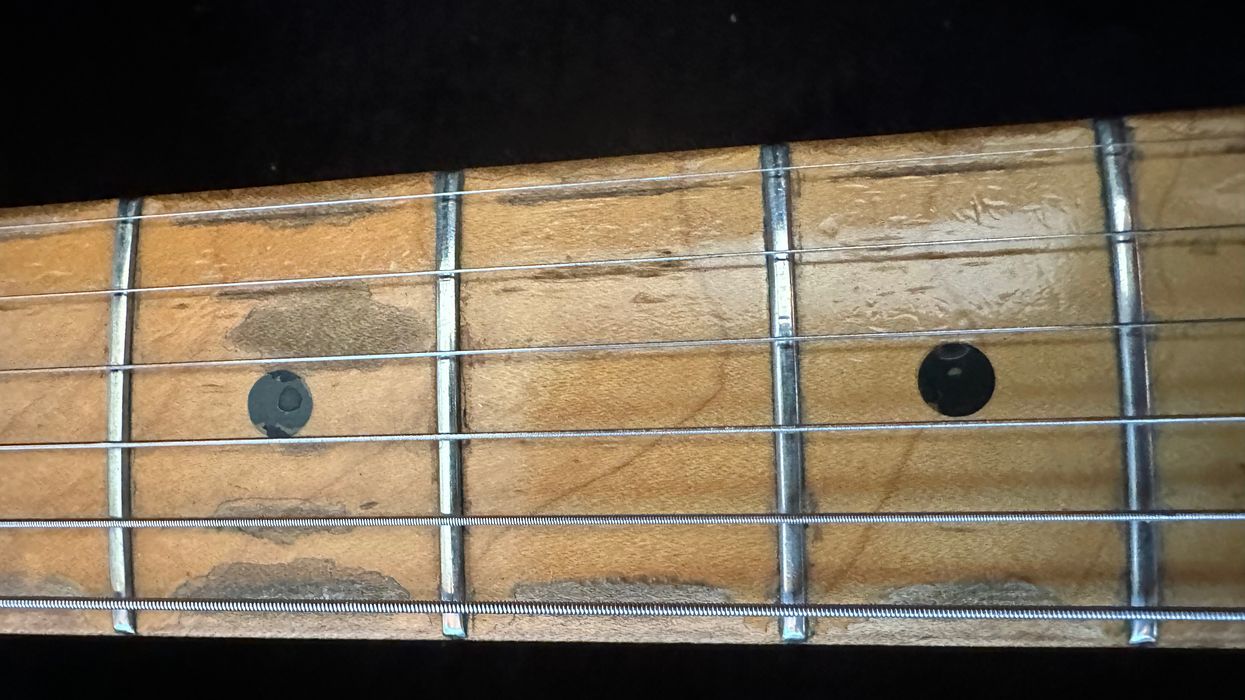

I am not a violin maker, but I’ve had my hands on some of Guadagnini’s and Stradivari’s instruments. While these instruments sounded wildly different, they had an unusual quality: the harder you plucked them the louder they got. That was enough to push me further down the rabbit hole of physics in instrument making. What made them special is a combination of deep understanding and an ability to tune the instrument and its vibrating surfaces so that it produced an extraordinary sound, full of harmonics and very little compression. It was the beginning of a document we live by at PRS Guitars called The Rules of Tone.

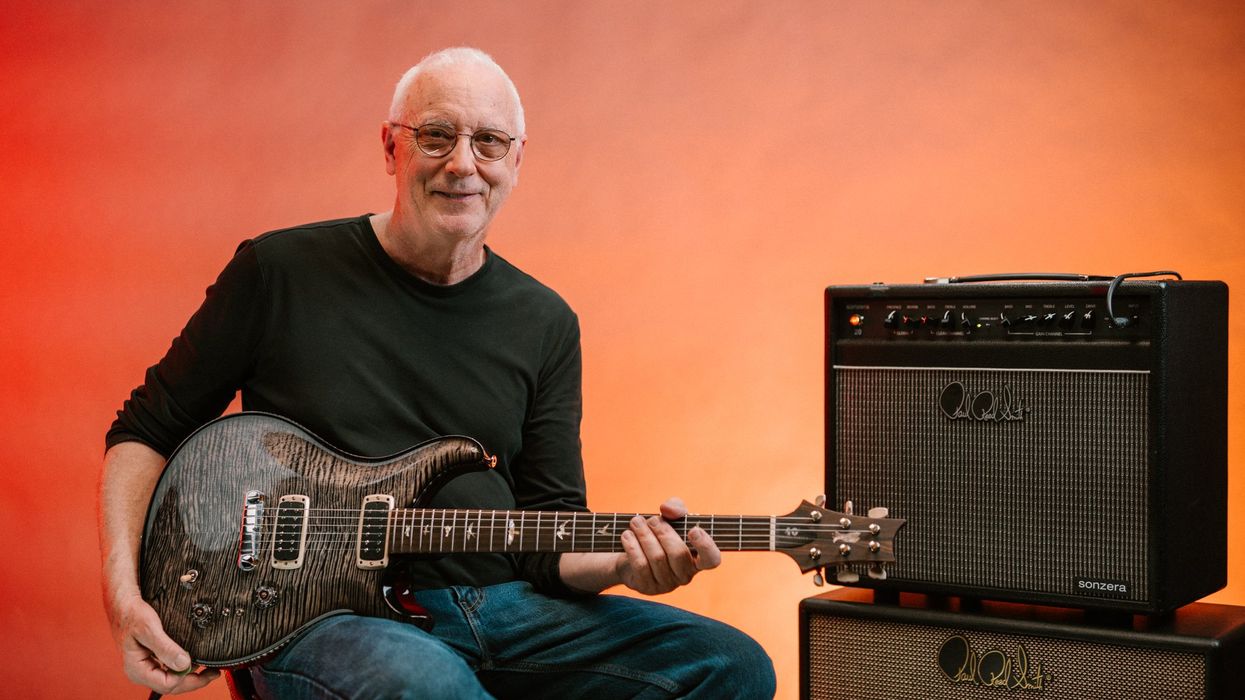

My art is electric and acoustic guitars, amplifiers, and speaker cabinets. So, I study bridge materials and designs, wood species and drying, tuning pegs, truss rods, pickups, finishes, neck shapes, inlays, electronics, Fender/Marshall/Dumble amp theories, schematics, parts, and overall aesthetics. I can’t tell you how much better I feel when I come to an understanding about what these masters knew, in combination with what we can manufacture in our facilities today.

One of my favorite popular beliefs is, “The reason Stradivari violins sound good is because of the sheep’s uric acid they soaked the wood in.” (I, too, have believed that to be true.) The truth is, it’s never just one thing: it’s a combination of complicated things. The problem I have is that I never hear anyone say the reason Stradivari violins sound good is because he really knew what he was doing. You don’t become a master of your craft by happenstance; you stay deeply curious and have an insatiable will to learn, apply what you learn, and progress.

“Acoustic and electric guitars, violins, drums, amplifiers, speaker cabinets–they will all talk to you if you listen.”

What’s interesting to me is, if a master passes away, everything they believed on the day they finished an instrument is still in that instrument. These acoustic and electric guitars, violins, drums, amplifiers, speaker cabinets—they will all talk to you if you listen. They will tell you what their maker believed the day they were made. In my world, you have to be a detective. I love that process.

I’ve had a chance to speak to the master himself. Leo Fender, who was not a direct teacher of mine but did teach me through his instruments, used to come by our booth at NAMM to pay his respects to the “new guitar maker.” I thought that was beautiful. I also got a chance to talk to Forrest White, who was Leo’s production manager, right before he passed away. What he wanted to know was, “How’d I do?” I said, “Forrest, you did great.” They wanted to know their careers and contributions were appreciated and would continue.

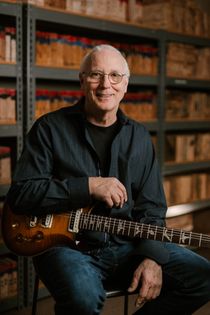

In my experience, great teachers throw a piece of meat over the fence to see if the dog will bite it. They don’t want to teach someone who doesn’t really want to learn and won’t continue their legacy and/or the art they were involved in. While I have learned so much from the masters who were gone before my time, I have also found that the best teaching is done one-on-one. Along my journey from high school bedroom to the world’s stages, I enrolled scores of teachers to help me. I didn’t just enroll them. I tackled them. I went after their knowledge and experience, which I needed for my own knowledge base to do this jack-of-all-trades job called guitar making and to lead a company without going out of business.

I’ve spent most of my career going down rabbit holes. Whether it’s wood, pickups, designs, metals, finishes, etc., I pay attention to all of it. Mostly, I’m looking backward to see how to go forward. Recently, we’ve been going more and more forward, and I can’t tell you how good that feels. For me, being a detective and learning is lifesaving for the company’s products and my own well-being.

Sometimes it takes a few days to come to what I believe. The majority of the time it’s 12 months. Occasionally, I’ll study something for a decade before I make up my mind in a strong way, and someone will then challenge that with another point of view. I’ll change my mind again, but mostly the decade decisions stick. I believe the lesson I’m hitting is “be very curious!” Find teachers. Stay a student. Become a teacher. Go down all the rabbit holes.