There have been many celebrated tonewoods throughout the history of lutherie. In the electric-guitar domain, ash, alder, and mahogany have been traditional choices. For acoustics, the famed Brazilian rosewood and Adirondack spruce have prevailed.

However, as regulations tightened and supplies dwindled, many legacy acoustic builders, such as Martin and Gibson, moved onto Indian rosewood and Sitka spruce. Because of this, from the late ’60s on, these woods continued to transform the industry standard. But our community has seemingly lost sight of a highly viable wood—the same wood that Stradivarius used to make some of the finest bowed instruments, and the same wood that has produced among the world’s most articulate Spanish-style guitars: maple.

“Builders such as John D’Angelico and Jimmy D’Aquisto followed in that tradition, inspiring makers such as Bob Benedetto and John Monteleone who continued using maple as a primary tonewood.”

At the birth of what would become the modern flattop guitar, classical builders routinely used maple to produce concert-level musical instruments. But as time has passed, maple has fallen to the “B-list” of tonewoods, where it doesn’t belong. Maple is an excellent tonewood that even has many advantages over other wood options.

Maple is readily available, especially when compared to its tonewood counterparts. Unfortunately, this domestic availability made it a go-to wood for many builders, including those who’ve misused it in lower quality instruments. Although this may have negatively impacted maple’s reputation, its accessibility is still advantageous, and maple still stands as an effective tonewood for builders with high musical standards. Unlike the exclusivity associated with some tonewoods, any luthier could have the luxury of building with mapleA testament to its quality, maple still remains a standard choice for archtop guitar makers. In the past, this included makers such as Gibson, who introduced the Lloyd Loar Master Series instruments that included the F-5 mandolin and the L-5 guitar which set the pace for the entire archtop world. Soon after, builders such as John D’Angelico and Jimmy D’Aquisto followed in that tradition, inspiring makers such as Bob Benedetto and John Monteleone who continued using maple as a primary tonewood.Recently, maple is seeing a resurgence in its use for quality guitar making and is becoming more accepted by consumers. This is mainly due to the high prices associated with typical tonewoods, like Brazilian rosewood, and the difficulty associated with transporting such exotic woods overseas. I’m a builder who loves to use woods like Brazilian, but some of the best instruments I have ever played were constructed from maple.

Maple is among the most beautiful-looking tonewoods, with some absolutely stunning variations, such as flame, bird’s eye, blister and quilted figures. Even though I am not a fan of quilted maple—due to its lower strength-to-weight ratio—I find most other options to be suitable for guitar making that I would play any day.

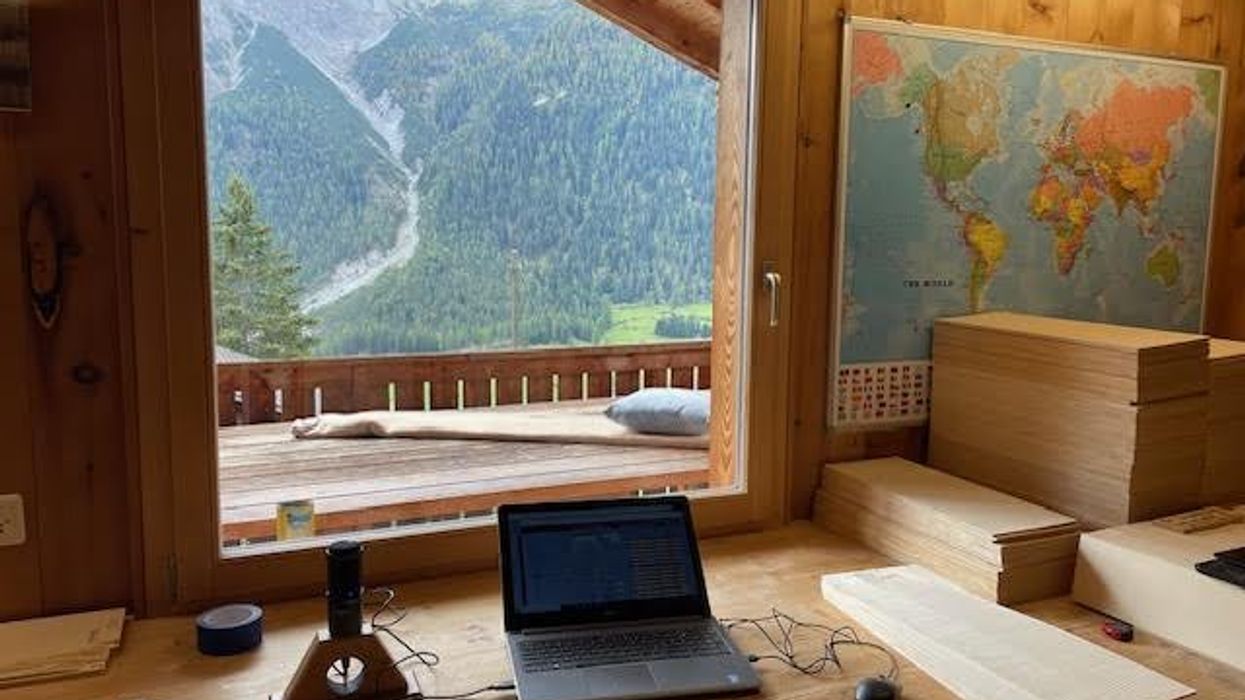

Galloup G-9CE, made with Michigan hard maple, finished in a hand-rubbed sunburst with nitrocellulose finish.

Maple also comes in many different densities and stiffnesses. Softer maples can range from wood so soft you can cut with your fingernail to varieties that can surpass in hardness some Indian rosewood, and hard maple can routinely surpass the strength-to-weight of other hardwoods. Remember, though, that regardless of whether it’s hard or soft, the species does not always dictate its sufficiency due to orthotropic characteristics. Boutique builders such as myself understand this principle, and we will carefully peruse woods that meet our criteria. I have had many sets of Brazilian rosewood pass through my hands that I would not deem musically acceptable, and I have also seen maple (generally hard maple) exceed the performance of such Brazilian rosewood sets. In fact, the next guitar I build for myself will be constructed out of figured hard maple I’ve had for twenty-some years that has proven to not only be musically competitive, but sonically outperform other options at many levels.

Another premier fact about maple is its sustainability. While it has to be managed like any other tonewood, there is an abundant supply of respectable, domestically harvested maple available.

Abundant availability coupled with new sonic rating systems will certainly contribute to a resurgence in maple. However, customer acceptability is a concern, and many guitar buyers are drawn to darker tone woods for back and sides. I have made many natural-finish, or “blonde,” guitars that did not sell well in the market. But when I made the same guitar and tinted the maple back and sides with a dark stain, they performed 60 percent better in sales. This is clear proof that the guitar-buying public buys with their eyes. (Maybe next time, give that maple guitar a little extra play time before discarding it as your final option.)

The bottom line is this: maple is a completely viable tonewood, and I am eager to see it employed to construct quality-level instruments and once again become a premier option. Additionally, I am hopeful that the market is uncovering what us wood junkies have known for decades—maple is just a great option, and a prime candidate for making great sounding, concert-level guitars.