What would one be most likely to discover in the basement of an old house in rural Alaska, deemed unfit for occupancy by local authorities? Smoked fish? A dog sled? A rare, possibly one-of-a-kind, turn-of-the-century banjo?

That’s exactly where this 1911 Vega Tubaphone tenor banjo was before it arrived at Fanny’s House of Music. It came by way of a local Alaskan musician who was helping move things out of the condemned house and found this instrument—over a century old, but looking as if it had left the factory earlier that week.

The rabbit holes of vintage banjo identification are myriad. It’s a Vega because of the stamp on the dowel rod, but why does it also say “Fairbanks Banjo made by Vega?” The serial number dates it to 1911, and of the banjo models Vega produced at that time—the Regent, the Imperial Electric, the Whyte Laydie, and the Tubaphone—this one is clearly a Tubaphone. Except Tubaphones never had an elaborate gryphon peghead inlay, so how can it be a Tubaphone? When did Vega switch from a grooved stretcher band to a notched one? And what the heck is a stretcher band, again?

That’s when it’s time to bring in the big guns.

Enter Karl Smakula, friend of Fanny’s and third-generation banjo expert. His grandfather Peter H. Smakula heard Pete Seeger in the 1950s and immediately bought himself a Kay banjo. He began repairing instruments and building banjos, eventually opening his own music store, where his son Bob also worked. Bob went on to open Smakula Fretted Instruments in 1989, where his son Karl also worked. Suffice it to say, if it’s a banjo, Karl and his family probably know about it.

“I would have never said the gryphon inlay was used on a Tubaphone until I saw this one,” says Karl. “My dad, who has seen everything, has never seen this.”

In the early 1900s, Vega was focused on guitars, mandolins, and brass instruments, but they were aware of the growing popularity of the banjo. The A.C. Fairbanks Banjo Company, a widely respected banjo maker, suffered a devastating fire in 1904 and made for a timely acquisition by Vega. (“After which Fairbanks made a hard pivot to bicycle parts,” reveals Karl.)

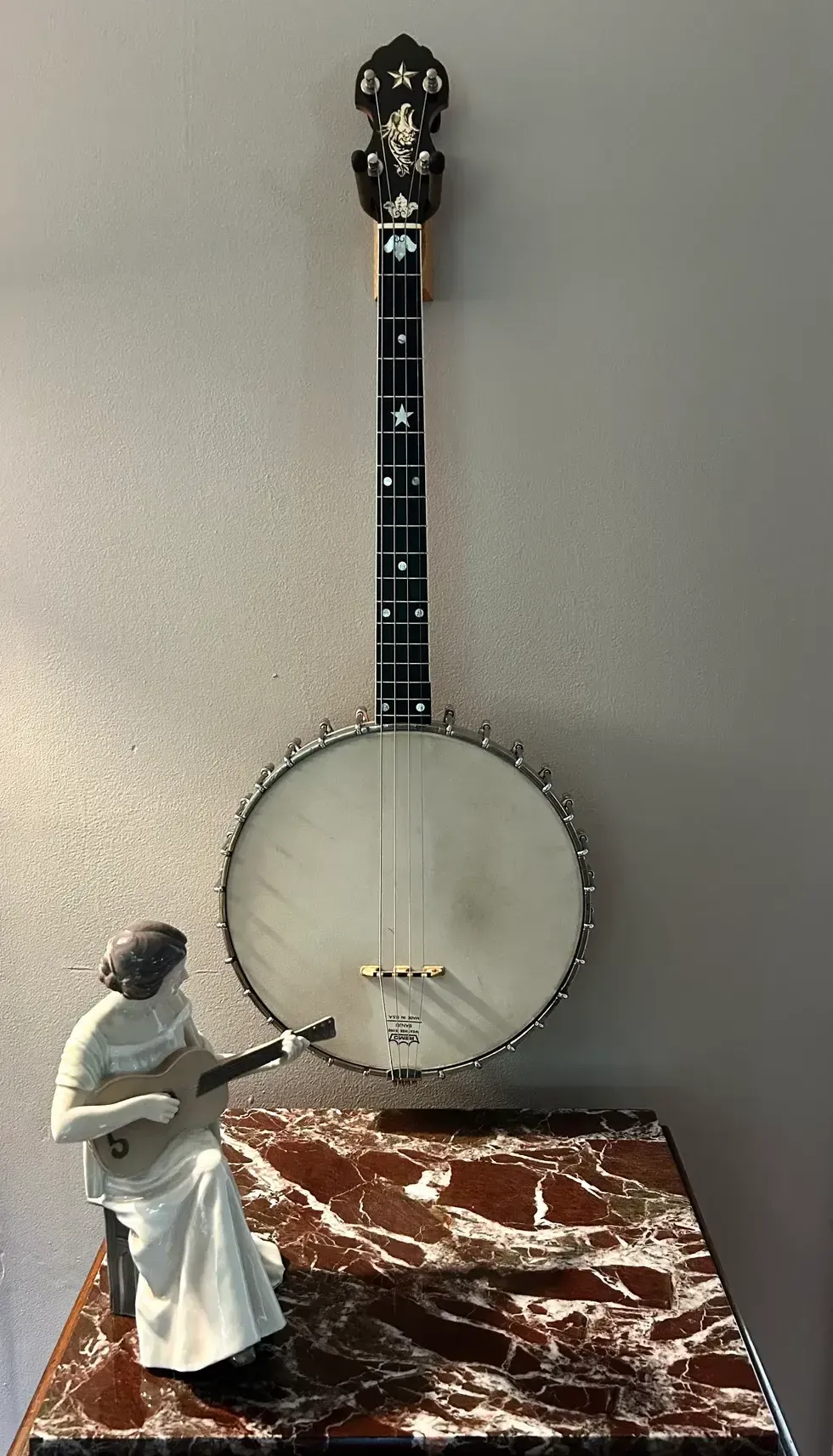

The striking gryphon inlay on the headstock makes this Tubaphone a very rare gem.

Photo courtesy of Fanny’s House of Music

Vega kept making the Fairbanks Whyte Laydie model, retaining the intricate gryphon peghead inlay and scalloped tone ring. In 1909, they introduced a new model called the Tubaphone, with a leafy “flowerpot” inlay and a brand new tone ring design featuring a sequence of holes drilled into the side. Where the Whyte Laydie sounded sweet and refined, the Tubaphone was louder and more aggressive. It quickly made a splash among banjo players, as this customer letter from the 1912 Vega catalog shows: “I have tried them all but from now on it will be a TU-BA-PHONE and nothing else for me. Refer any inquiries you like to me ... and I will show them what a real banjo is.” Banjo players have always been an opinionated bunch!

Tubaphones are still highly valued among old-time musicians today, although it is important to note they were intended for what’s called “classic” banjo playing when first produced. Derived from classical guitar playing, it uses bare fingers and gut strings. While this style is little practiced these days, it doesn’t take a big intellectual leap to see how classic banjo combined with African banjo playing, jazz, and two-finger style to form the bluegrass “Scruggs” style we’re familiar with today.

“This old gal made it from rural Alaska to Nashville, nearly stumping two generations of banjo experts.”

“This banjo’s had a life, that’s for sure,” says Karl with a laugh. Karl noted the dowel stick at the end of the neck matches the rim, indicating the neck and gryphon inlay are, improbably, original to this Vega Tubaphone. “It shows they were figuring out what they were doing.”

This old gal made it from rural Alaska to Nashville, nearly stumping two generations of banjo experts. It’s in superb condition, and everyone who takes it for a spin at Fanny’s agrees with the 1912 Vega catalog, which proclaims, “There is Tone Value to the Vega with which every player should become acquainted. To know and realize that Vega Construction is the easiest way to advancement means that your future Musical Prosperity is assured.” It’s safe to predict the Tubaphone will be assuring musical prosperity for another 114 years at least.

SOURCES:

Banjo Studio, Vega 1912 banjo catalog, Fanny’s House of Music, Smakula Fretted Instruments, Banjo News, Vintage Instruments, Mugwumps, Vega Style M webpage, Bill Evans YouTube channel.

Whether or not Jimi Hendrix actually played this guitar might come down to how lucky its buyer feels.Photo courtesy of Imperial Vintage Guitars Reverb Shop

Whether or not Jimi Hendrix actually played this guitar might come down to how lucky its buyer feels.Photo courtesy of Imperial Vintage Guitars Reverb Shop