Few effects delivered as much aura and musically transformative power per buck as Electro-Harmonix’s Sovtek Big Muffs from the mid ’90s. Mine set me back probably $50. But man, I might as well have stolen Excalibur from the clutches of King Arthur.

Up to that moment, my piggyback Fender Tremolux, Tube Screamer, and Rickenbacker was perfect for thrashing out ’60s Kinks riffs. But with the Big Muff in the mix, my little rig became a monster—a wrecking ball capable of the potency I savored in Black Sabbath and Dinosaur Jr. From that moment on, my amplifier would be intolerable to the public outside the confines of a rented jam space. I suspect I went to bed that night pondering, like Robert Oppenheimer, tales of Prometheus and the Bhagavad Gita. The Big Muff had unleashed a horrible new power.

“The Fade Font ’94 possesses all the signature qualities of a Big Muff—sustain, mass, and megatonnage.”

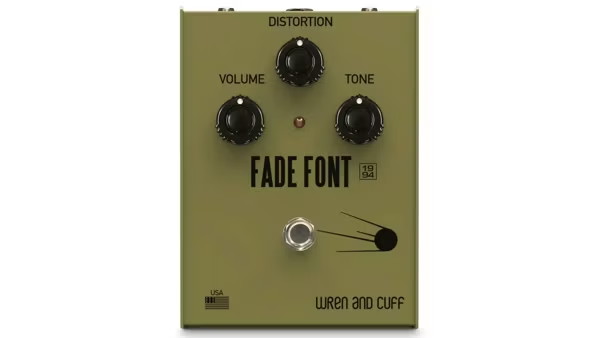

Today the Big Muff’s might is legendary, and thanks to a couple of decades of cloning and reissues its power has proliferated among players. But Big Muffs sing many songs. Like their human creators, they are full of quirks, and Wren and Cuff’s Matt Holl and protégé Ray Rosas study these oddities and irregularities fastidiously. The newest product of Holl’s obsession is the Fade Font ’94—a beautiful homage to a ’90s “Tall Font” Sovtek Big Muff in Holl’s sizable collection built with unusual components that shifted its personality to brasher ends. The Fade Font ’94 possesses all the signature qualities of a Big Muff—sustain, mass, and megatonnage. But it’s also nastier and illuminated at the edges by a ripping high-mid ferocity that counterbalances the creaminess that is the signature of most ’90s Big Muffs.

Built to Bruise

The charms of the Fade Font ’94’s olive drab, steel-slab design will no doubt elude some. But as someone who keeps their Sovtek Big Muff on a sort of informal mantle in my studio, I was genuinely thrilled to see how Wren and Cuff reproduced the original’s enclosure with such exactitude and quality. The dimensions are, save for very minor deviations, identical. At a few paces, you’d never suspect you were looking at anything other than an original Sovtek. The difference in quality, however, between Wren and Cuff’s unit and an original Sovtek is easy to see and feel. There’s a proper footswitch. The knobs (near-perfect replicas of the originals) turn with a smooth secure sense absent in Sovteks. And on the inside, the relatively simple circuit is executed masterfully on a through-hole circuit board. I also suspect the paint on the Wren and Cuff won’t flake off within weeks, and I won’t miss the Sovtek’s plastic jacks. So, yes, on the quality and craft side of the equation, Wren and Cuff deliver.

But it’s the sound that puts the Fade Font ’94 over the top. And Matt Holl was right to be excited by the sonic signature of the Muff that inspired this one. The primary design difference in that Big Muff is its use of 150k pots rather than the 100k pots most Muffs use. Holl found several component values elsewhere in the circuit that didn’t match Big Muff design norms. The sonic sum is what you hear here, and in Muff terms it’s something special.

Side by side, five Big Muff circuits can sound equally great for five different reasons. But the Tall Font conveys a sense of balance and playing to strengths—like a top-notch analog desk mix of a record, or a great mastering job. And it makes the Fade Font ’94 sound quite like listening to a Big Muff greatest hits record. It’s plenty bassy, just like a Sovtek should be. But the airy lower-midrange seems to siphon away excess low-end energy that might make a bass trap and convert it to low-mid purr. The high-mid, too, is very activated and detailed without flirting with brick-wall midrange. The top end is full of air, while the low-mid purr becomes a growl. It’s just really balanced across its gain structure and feels exceptionally alive as a result.

The Verdict

If you played the Fade Font ’94 without the benefit of side-by-side comparison with other ’90s or ’90s-style Big Muffs you might be hard-pressed to recognize the differences. If you have the ability to do so, though, it becomes hard to un-hear the shift in accent that makes it sound so much more sonorous, well-rounded, and at times, extra aggressive.

Obviously, there are practical downsides to the Fade Font ’94’s lovingly, exactingly executed big-enclosure format. Any player with more than a few additional pedals will struggle to accommodate the big footprint without scaling up to a bigger pedalboard. On the other hand, the Fade Font’s flexibility gives you justification to pare back your fuzz collection. Maybe, like I did over the course of this test, you’ll succumb to the Fade Font ’94’s brutish charms so completely that you’ll find everything but a delay pedal superfluous. For such minimalists, well-heeled maximalists with roadies, pedal aesthetes, or studio rats more concerned with delicious sounds than pedalboard space, the Fade Font ’94’s size won’t get in the way of putting it to use.

Reflecting on my $50 Big Muff purchase back in the ’90s—and the many times I put it back together with a cheap Radio Shack soldering kit and gaffer’s tape—it’s hard to imagine that such a close relative could be elevated to this level of luxury. But once again, Wren and Cuff has shaped magnificence from merely modest perfection. And any player who loves the Big Muff owes it to themselves to experience this intriguing, engaging variation on the theme.

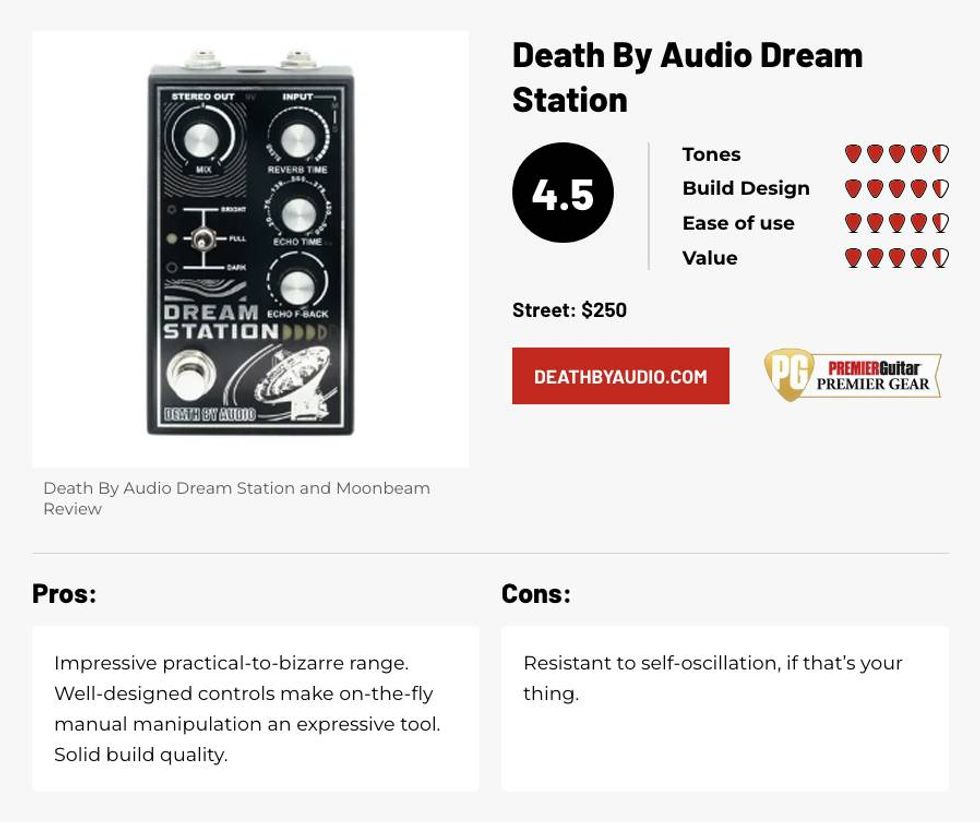

Death By Audio Dream Station and Moonbeam Review

Death By Audio Dream Station and Moonbeam Review

Death By Audio Dream Station and Moonbeam Review

Death By Audio Dream Station and Moonbeam Review