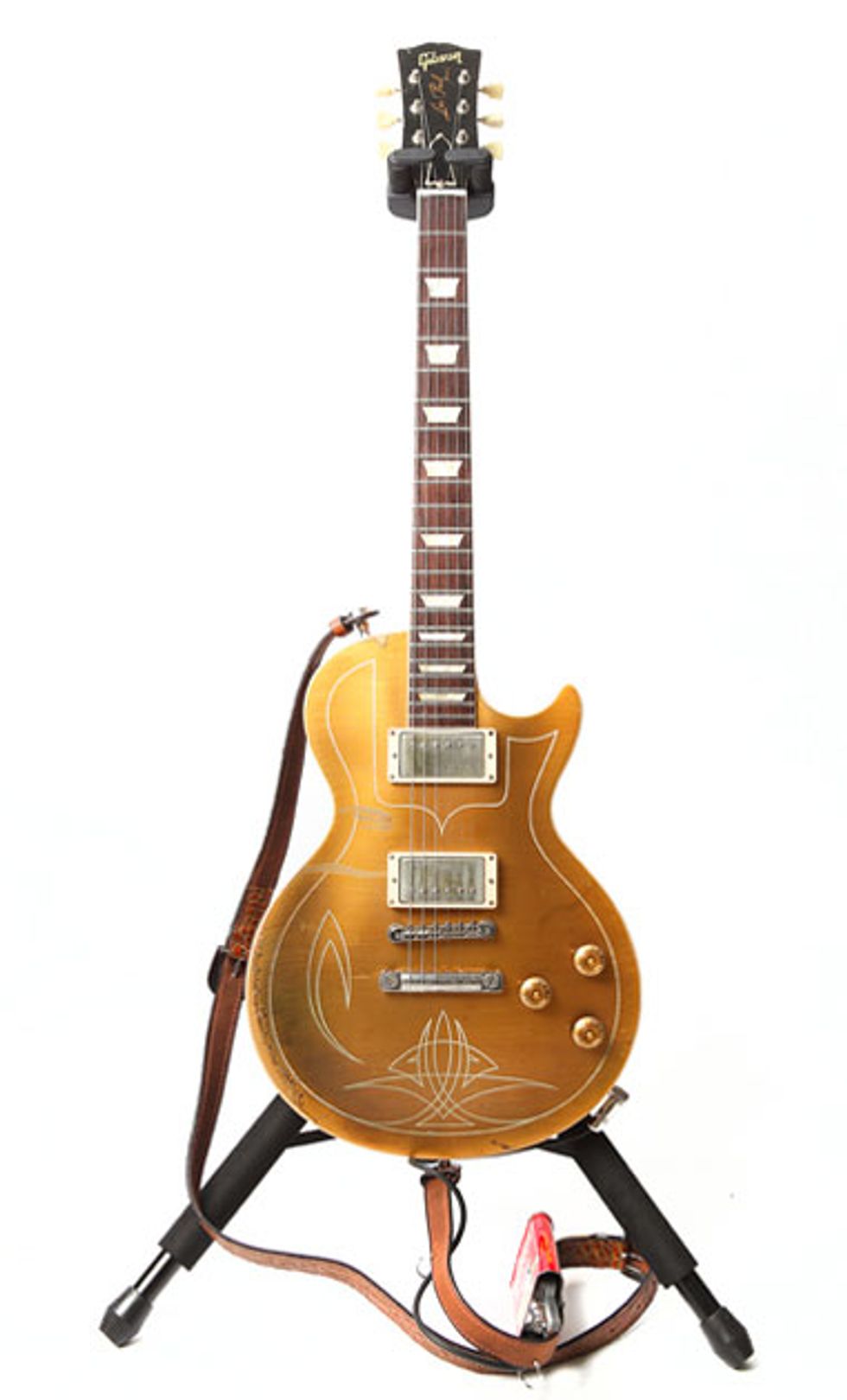

This axe is a prototype for a Gibson Goldtop (2009). It has a chambered body and custom 3-knob wiring with master tone, bridge volume, and neck volume on a push/pull (down is off, up is on). There are only two tones available with this setup: bridge pickup and both pickups out of phase. Both pickups are SD Pearly Gates.

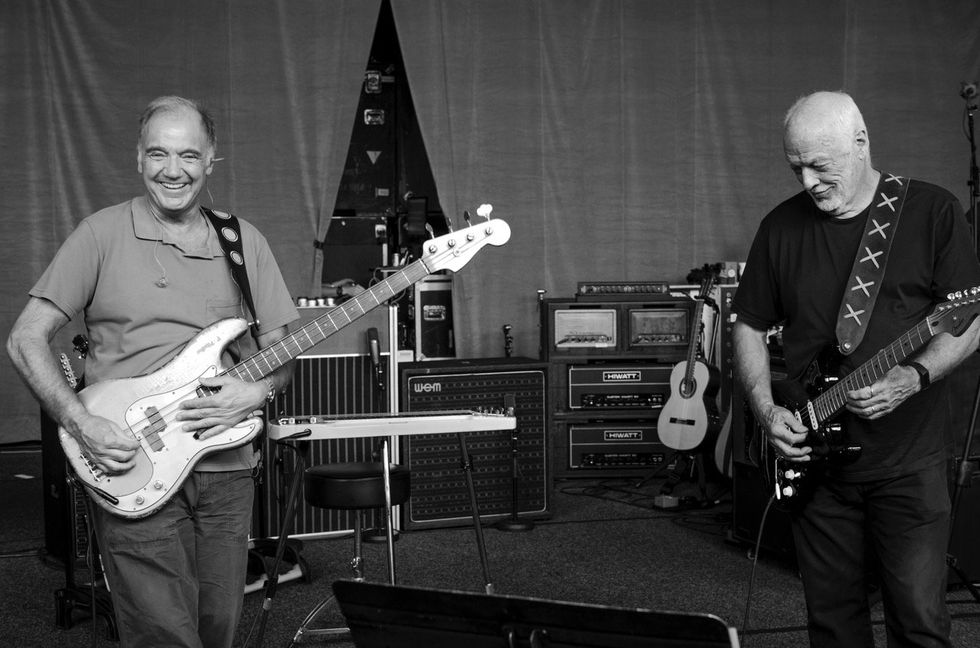

ZZ Top approaches gear like they approach facial hair: Go big or go home. Billy Gibbons’ tech Elwood Francis and Dusty Hill’s tech Ken “TJ” Gordon give us the behind-the-scenes rundown of the current touring setup.

Billy Gibbons’ Gear

Here’s a glimpse at what Billy’s been using live, but let it be known that it’s already changed. “We started the tour using the Les Pauls for the encores, but that gave way to whatever guitars we happened to pick up along the way,” said Billy Gibbons’ tech Elwood Francis from the road in mid-November. “Things change at the drop of a hat. In the past week, we've acquired four guitars and six fuzz boxes—and the tour only has three more gigs.”

Dusty Hill’s Gear

Tech Ken “TJ” Gordon describes Dusty Hill’s bass tone as, “Texas blues with a little nastiness and a lot whoooo!” Here he guides us through Hill’s gear, including a collection of basses that were custom-made to match the guitars of bandmate Billy Gibbons.