It’s tempting to view a chord progressionas a sequence of fixed note formations thatwe grip and release, one after the other.This makes sense on a tactile level because,after all, it‘s what our fingers are doing. Butif we only think of chords as discrete grips,we may overlook how each one is connectingto its neighbor. And when we don’t payattention to these harmonic transitions, wecan wind up lurching around the fretboard,playing voicings that don’t dovetail musically.This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. In fact,some styles demand sliding up and downthe neck with barre or power chords to createa jagged effect. But, as we’ll discover inthis lesson, there are other ways to navigatea progression.

One approach involves making the smallestpossible shifts between the notes in one chordand the next. This technique yields a flowing,molten sound, and it’s well worth exploring.

Rules of Engagement

The concept—which, incidentally, we’reborrowing from choral, horn, and string arranging—is to have the notes in one chord move byeither a half-step or whole-step to the notesin the subsequent chord. Occasionally, weinterrupt this stepwise motion with a leapof a minor third (three half-steps), but that’sthe largest move we make. Sometimes, oneof the notes remains the same as we switchchords. This common tone acts as sonicglue, binding adjacent voicings, even asthey change.

It’s fun to visualize this process as movingbeads on wires. In other words, imagineeach chord tone is a bead that either staysput or shifts up or down on its string byone, two, or three frets (a half-step, whole-step,and minor third, respectively) tomorph into the next voicing. It’s a game:Can you play a progression without breakingthese strict rules?

Warming Up

So we can clearly picture the note-to-notemovement, let’s keep things simple andstick with three-note voicings on the topthree strings. Most of the chords we’ll playin this lesson contain four or more notes intheir full form, but we’re going to cherry-pickthree that allow us to follow our beadgame rules.

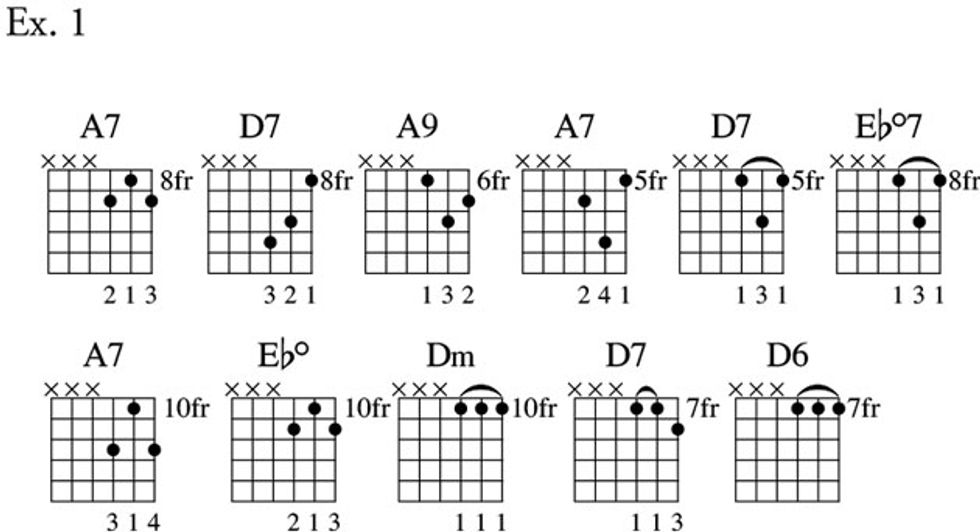

For starters, play through the voicings inEx. 1 to loosen up your hands and getfamiliar with the fingerings we’ll soon stitchinto a progression. Many of these will beold friends, but some—D7 and A9, forexample, in grids 2 and 3—might be new.

As you fret each of these chords, noticehow three do double duty, depending onwhere they’re positioned: A7 and Ebdim (grids1 and 8), D7 and Ebdim7 (grids 5 and 6), andDm and D6 (grids 9 and 11). This “sharedshape” phenomenon happens becausewe’re selecting a subset of a chord’s availabletones. (If we were to fret the chords intheir entirety, we’d spot their physical differences.)Expert rhythm guitarists routinelyuse multi-purpose fingerings to craft theirparts. It takes time to master such musicalsleight of hand, but the payoff is huge.

Click here for Ex. 2

Let the Games Begin

Now it’s time to put our rules into action byplaying Ex. 2, a 12-bar blues progressionin the key of A. As you change the first twochords, watch those beads shift when youmove from A7 to D7. Check it out: On the1st string, the top note, C#, drops a fret toC. On the 2nd and 3rd strings, each notemoves up two frets, (G–A and E–F#, respectively).Excellent! We’ve created contrarymotion, which serves to draw listeners intothis chord change.

If you peer closely at the A7–A9–A7 changesin measures 3 and 4, you’ll see common tones(for instance, the 2nd-string G occurs in allthree voicings), two whole-step moves, anda minor-third leap. Nice and tight—so far,so good.

The A7–D7 shift (measures 4 and 5) is veryeconomical, consisting of a common toneand two half-step drops. Conversely, theD7–Ebdim7 change incorporates three upward,minor-third leaps. This parallel movementis immediately balanced by the contrarymotion in the Ebdim7–A7 change across measures6 and 7.

At this point, you’ve seen enough to knowhow the bead game works. As you completethe progression, take a moment toevaluate each chord change and track itsnote-to-note movement. You’ll find thatright through the end of measure 12, everychange consists of common tones and half-step,whole-step, or minor-third moves. Theonly exception is when we reach the end ofmeasure 12 and jump back to the top to repeatthe progression. Because measure 12’s E7 andmeasure 1’s A7 share the same fingering, try slidingfrom E7 to A7 for a dramatic break fromour otherwise frugal motion.

By the way, the A7–Ebdim–Dm–A7 move in measure8 makes a dandy turnaround or intro. Withlittle effort, you’ll be able to insert it into ablues or even a fingerpicked folk song.

Pressing On

The next step is to incorporate the beadgame concept into your playing. We’ll beusing this technique in upcoming lessons,but to really own it, you’ll need to exploreit yourself. One way to get started is totranspose this lesson’s progression down anoctave, placing it on lower strings. Thoughthe chord shapes will look different—andyou’ll find more than one place to fretthem—the common tones and half-step,whole-step, and minor-third moves will allremain the same.

Next month, we’ll look at a trick for generatingvoicings that are tailor-made for a hybrid,plectrum-and-fingers picking technique.

Ah-ha!

Stepwise motion. When a melodic line moves up or down in half- orwhole-steps (distances of one or two frets, respectively), it employsstepwise motion.

Contrary motion. When two lines move in opposite directions—oneascending while the other descends—they produce contrary motion.This can also occur during a chord change when one voice moves upas another moves down.

Diminished triads and diminished 7 chords. Every chord typehas a formula that’s derived from a major scale. (For more detailson scale and chord formulas, see the November 2010 Rhythm &Grooves.) The formula for a diminished triad is 1–b3–b5, or the first,lowered third, and lowered fifth tones of a major scale. We add afourth note to generate a diminished 7 chord, which has a formulaof 1–b3–b5–bb7.

To identify the notes in a diminished chord, simply apply the appropriateformula to a parallel major scale. For example, to unpack aCdim or Cdim7, we start with a C major scale (C–D–E–F–G–A–B–C) andthen run the corresponding formulas. This yields C–Eb–Gb (Cdim) andC–Eb–Gb–Bbb (Cdim7). Sonically, a bb7 note is the same as a 6, so manymusicians choose the latter as a kind of shorthand when spelling adiminished 7 chord. Using this informal approach, we’d identifyCdim7’s component notes as C–Eb–Gb–A. When two notes sound the same but are named differently—such as A and Bbb—they’re considered enharmonic equivalents.