Photo by Paul Haggard.

When people toss out the saying “It’s good to be king,” it’s usually a wry reference to obscene levels of prosperity enjoyed by a privileged few. But for Kings of Leon, it may have acquired had a wry ring for an entirely different reason over the last few years. Between cancelling a 2010 concert due to pigeon poop—and the, uh, crap storm of internet jabs the incident generated—not to mention having to bail on their 2011 U.S. tour due to singer/rhythm guitarist Caleb Followill’s alleged alcohol problem, the new decade didn’t exactly get off to a grand start.

Who knows exactly what went on behind the scenes during the downtime? Things can get hairy in families, and a family band can’t be any different. It was rumored that the acrimony among brothers Caleb, Jared (bass), and Nathan Followill (drums), and cousin Matthew Followill (lead guitar) ran so deep that they’d inevitably hang up their crowns.

That last bit of conjecture was false. Kings of Leon’s sixth LP, Mechanical Bull, came out this fall, and between its title and song titles like “On the Chin,” “Comeback Story,” and “Work on Me,” it seems to address the drama head-on. The music has the hallmarks of a classic Kings album, if a more grown-up one. “Rock City” bristles with southern-fried feedback. “Don’t Matter” is relentless with its fuzzy, world-weary vibe. “Beautiful War” broods with atmospheric, Joshua Tree-like warmth. “Coming Back Again” features bass guitar and toms galloping in unison alongside warbling, echo-laden guitar hooks.

It’s the sort of comeback that fits perfectly with the smug declaration of Mel Brooks’ King Louis XVI character after kissing a ravishing courtier in History of the World, Part 1: “It’s good to be king.”

We recently spoke to Matthew Followill about his affinity for hollowbodies, how synth lines inspire his guitar lines, and how he deals with being goaded by his cousins/bandmates while tracking solos in the studio.

You guys took some much-needed time off before working on this album. How did that affect the writing of Mechanical Bull?

We had been going really hard for a long time—I think it was eight or nine years—so it worked out well. We were all so excited to get back together and start writing for the album.

Did you play much guitar during the break, or do you prefer to set it aside when you aren’t recording or touring?

I’m sure it’s not what people want to hear, but when I think back about that year I can barely remember playing guitar at all. It’s weird though, because when I did pick it back up, it was like an old friend, and I was really excited to play again—and I felt like I was better. It’s hard to explain. It’s like when you work out a muscle, and then you take a week off and let the muscle heal, and it’s stronger.

Did you find that your playing approach had changed?

I listened to a lot of music on the time off, because on the album before [2010’s Come Around Sundown], I had a bit of writer’s block and definitely wasn’t feeling very creative. Listening to a lot of music helped me see what other guitar players and bands were doing. I wasn’t dissecting albums or anything like that, but I think it helped a lot when it came time for writing.

What were you listening to?

It’s weird, but a lot of the bands I like don’t have a strong guitar player. There’s this band called Wild Nothing that’s kind of pop/indie-sounding. I listened to the Horror’s record Skying, and some Tame Impala. Then you have the old classics. I got back into Thin Lizzy for a while, and some ZZ Top for a minute. But even bands that use a lot of synths help me picture the synth-y stuff as a guitar part, and I’d think about how I could get there using pedals and stuff like that.

When you reunited to write and record, what was the collective thinking like?

I just remember that we kept reassuring each other that this album had to be great—or that at least we had to think it was great. We kept saying, “If it’s not great, we’re just gonna take more time off, and we will not come out with something until we, as a band, think it’s great.” In the past, we always felt this pressure—usually the label just sticks us in there and they’re, like, “You have six weeks.” But this time we built a studio and had all the time we wanted.

With all the band’s negative press, did you feel you had something to prove?

It’s hard to see bad reviews and get compared to, like, Creed or Nickelback. I don’t understand those comparisons all that much. At some point you’ve just got to be, like, “This is what we love to do, so we’re just going to keep doing it and forget about all those people and know that there are fans of our music out there.”

It’s an eclectic record. There are bluesy elements, anthemic rock moments, country and rockabilly vibes. Is it tough to work out the band members’ various stylistic tendencies?

We all have very different tastes, but it all comes together. I like the more atmospheric stuff—the bigger, more meaningful type of songs, like “Beautiful War” and “Tonight” and even “Coming Back Again.” Then you have Caleb, who likes the more country singer/songwriter types, like “On the Chin” and “Comeback Story.” Jared is kind of with me, so it all comes together. One song can be very close to a bluesy/country song, and the next song can be this massive-sounding, arena-type thing.

U2 seems to have been an influence on your playing, if not on the band as a whole.

The Edge has been a huge influence. A lot of people can rip on the guitar and do crazy solos—and that’s awesome, that makes you really talented—but I think it’s a talent to be able to write a guitar part that changes the whole song. That’s a beautiful thing in and of itself, and the Edge does that great.

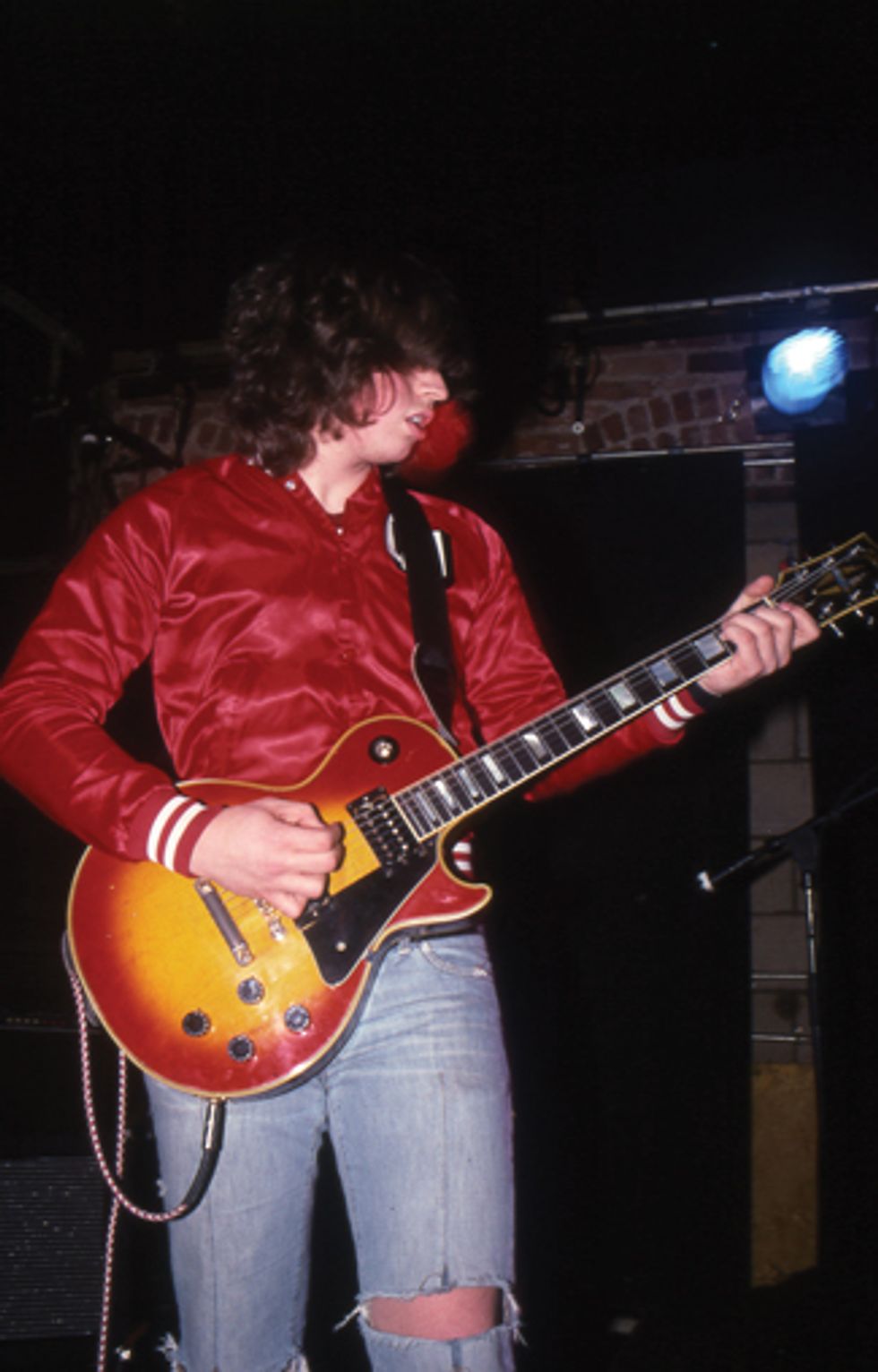

Photo by Frank White.

When Kings toured with U2 back in 2005, did you get to interact with the Edge much?

We’d say hello and whatever, but we didn’t hang out and talk guitar or anything like that. But his guitar tech let me go onstage one day at soundcheck and look at all of his stuff, and it blew my mind. At that point, I just had a guitar, an amp, a reverb pedal for one song, and an overdrive pedal—for a 45-minute set. So when I went up there I was just, like, “God, he has to use five different pedals for one song. It creates one sound,and then that part’s over, and he doesn’t even use those pedals again!” A lot of people say we changed after that tour. I remember touring with Secret Machines, and their guitar player Benjamin Curtis has a crazy amount of pedals, too. That’s when I first thought, “Maybe we should make a change.”

Kind of like what you said earlier about taking synth parts and translating them to guitar.

Absolutely. On some songs I’ll put a delay on it with a reverse, and then I’ll put the guitar on the bass pickup and roll out all the treble and then do that kind of warbling thing where you go pick back and forth really fast so it sounds just like a sweeping synth. I did that on three or four songs this time, just to lay a background down. It’s a way to challenge yourself—like, “How can I make this song really good without playing a standard lead guitar part?” I always want people to go, “Is that a guitar? What is that?” On a couple of songs—like on “On the Chin”—I tried to make the guitar sound like a steel guitar using a Whammy pedal and reverbs and other octave pedals.

How did you play that intro lick on “Coming Back Again”? It sounds like you’re leaning on the tremolo arm or something.

There are actually a couple of things going on. I was playing an older Fender Thinline Telecaster with a Bigsby, and then I was using an Eventide Space pedal, which is probably my favorite pedal. It has that modulation where the reverb mods after it goes for a second. It goes down or it goes up, whichever way you choose. When you hit the note, it sustains and then drops slowly. It was a combination of me going for the Bigsby and the mod on the reverb. That’s probably my favorite tone on the whole album. That was Angelo [Petraglia] though, and we've got to talk about Angelo: He produced the album, and he brought in his collection of stuff, and it just sounds amazing. Every cool sound and every great guitar tone is from him. He has so many old amps that he’s redone. And he has so many old guitars—like 50 guitars that are all over $5,000 each—and he brings them in and we just go crazy.

You’ve been a Gibson and Epiphone guy for so many years. Was it weird to play Fenders for this record?

It was awesome. I used that Thinline on a lot of songs. It just fit in with everything, and I couldn’t get anything else to sound quite as good. I used it on “Beautiful War,” “Coming Back Again,” and “Tonight.” It’s just got that twang thing that sounded really good with that reverb I was talking about earlier. But for every record, I just use whatever sounds good. I’ve never been, like, “It’s gotta be Gibson.” I would play a $20 pawnshop guitar if it sounded cool. We also used a couple of Fender amps—a Princeton and a Bassman—on quite a few songs.

Have you been taking Fenders out on the road?

I don’t play the Fenders live, just because I have a thing going live that I feel comfortable with, and I would be a little nervous to change it. Maybe on a big tour I could do that, but right now we’re just in and out for festivals and stuff, so for me to put a new amp or a new guitar onstage for one or two songs would be kind of weird.

For many years your main amp has been an Ampeg Reverberocket. How did you get turned on to that?

I can’t really remember what got me into the Reverberocket, but it was that and an ’83 Epiphone Sheraton. It was all about how good I could get it to feed back. I could hold a note and it would just start humming, and I thought, “That’s so awesome!” I used that on an album to get a lot of feedback, and then I thought, “I have to be able to recreate that.” So I stuck with hollowbodies, and I’ve been too nervous to change.

Matthew Followill's Gear

Guitars

2006 Gibson ES-137

1983 Epiphone Casino

Fender Thinline Telecaster

Amps

Ampeg Reverberocket 2x12

Fender Princeton

Fender Bassman

Effects

DigiTech Whammy

Boss ME-50

Boss PS-5 Super Shifter

Visual Sound Route 66

MXR Micro Amp

Eventide Space

Electro-Harmonix POG

Ernie Ball volume pedal

DigiTech DigiVerb

Line 6 Verbzilla

Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler

Dunlop Cry Baby wah

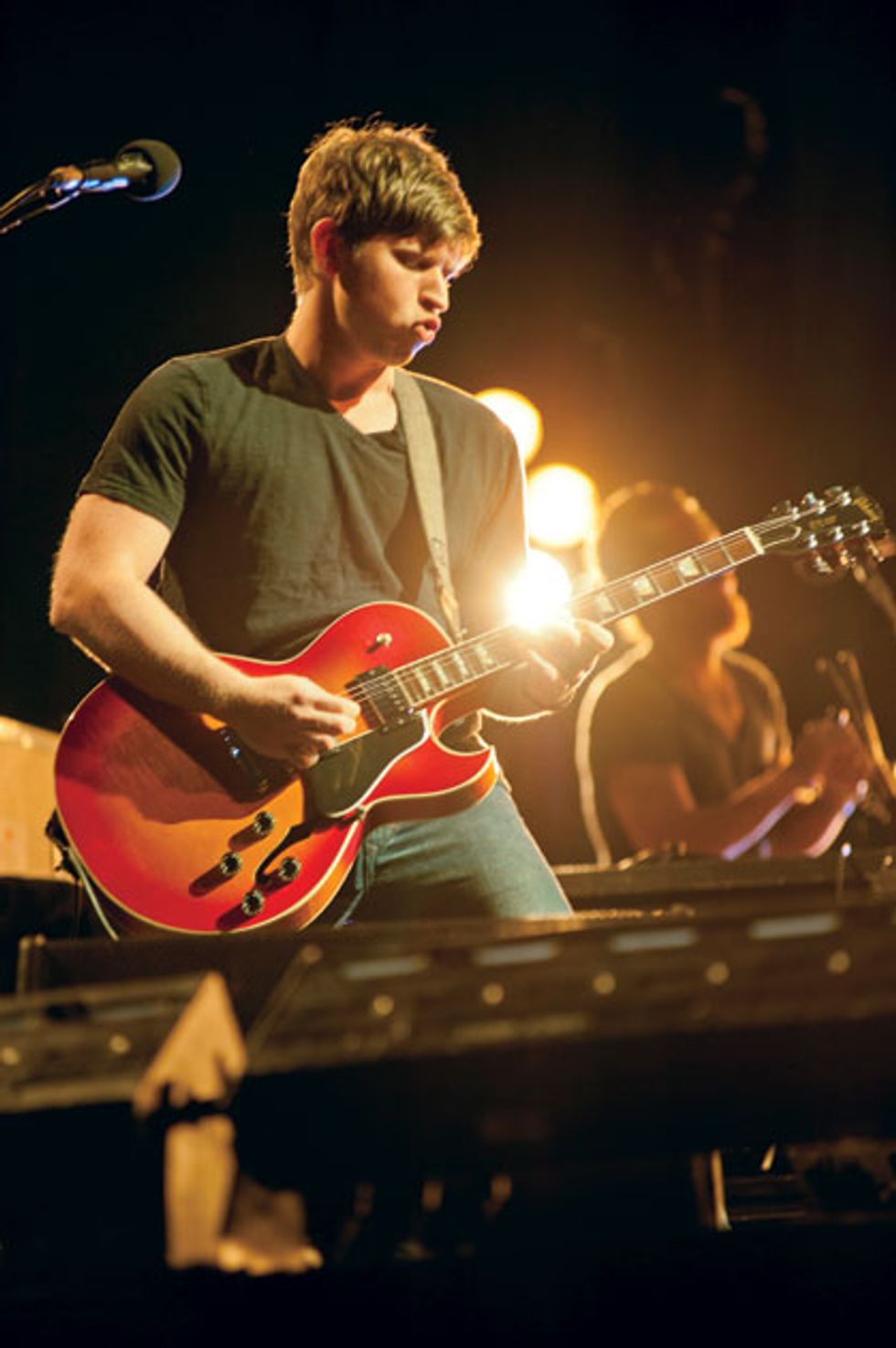

You’ve been playing a Gibson ES-137 as your main gigging guitar. What about that instrument appeals to you?

I think that was originally a rental, or Gibson wanted me to try it out—that’s usually the way these things happen. I remember Nacho [Followill, guitar tech and cousin] came in to soundcheck and said, “You gotta try this out. It’s really tough.” So I put it on and it was really strong—a lot grittier than the Sheraton, and it was easy to play. Everything just felt great about it. I played it for one show and the rest is history.

When you play one instrument almost exclusively for so long, does it become something of a comfort blanket? Or is it more about the fact that you’ve figured out what you can and can’t do with it?

I know exactly where to stand in front of the amp to get this sound or to make it feed back. I’m comfortable with it and I know it so well that it’s like, “Why change?” I started out with a Les Paul and played that for about three years, then I went to the Epiphone Sheraton for about three or four years, and now I’ve been on this 137 for maybe five years, so I’m sure there’ll be a change soon. I’m just not sure what that will be.

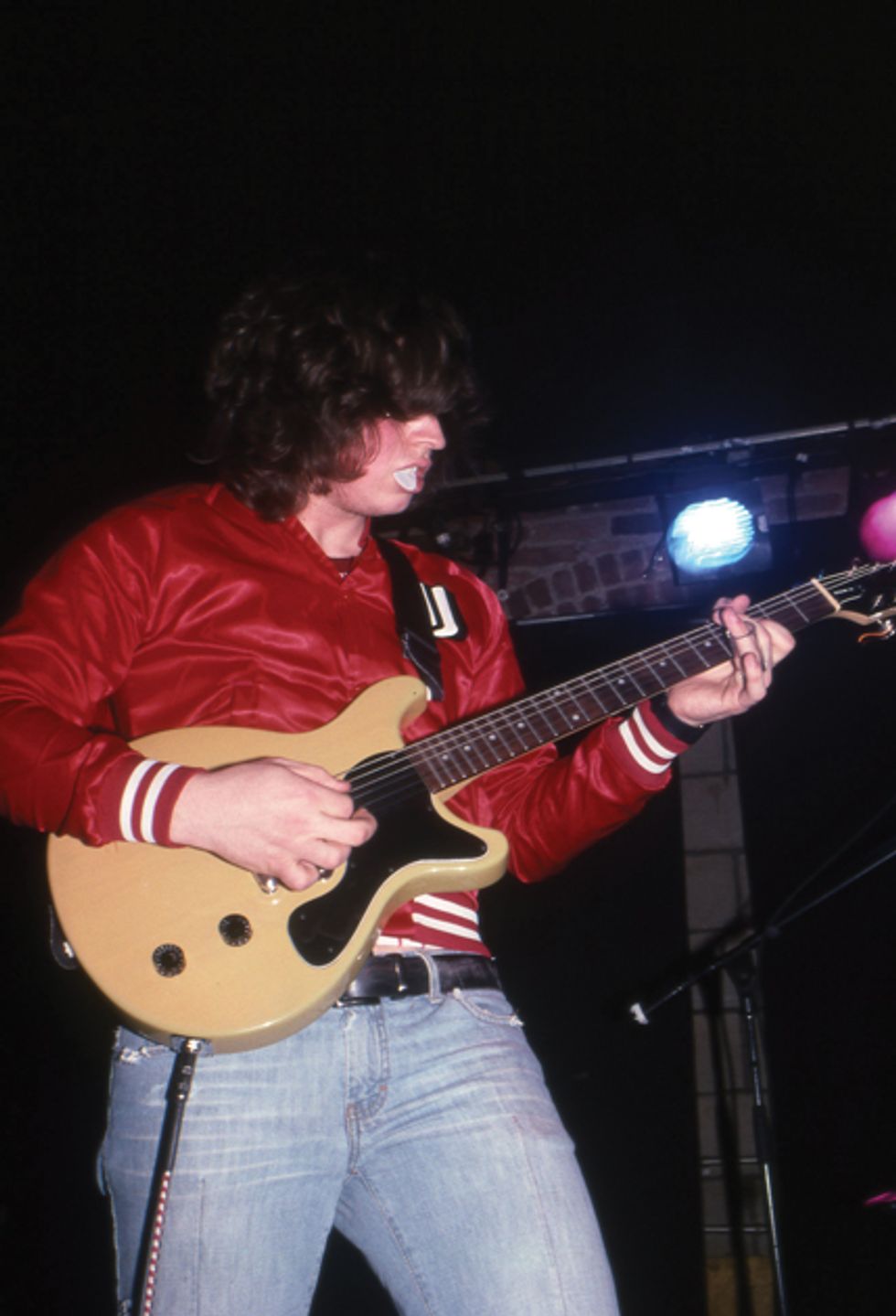

Photo by Frank White.

You have a knack for switching between tight, spare-sounding parts, like on “Beautiful War,” and then really ripping in looser moments, like the roaring solo on “Don’t Matter.”

I think that’s just from playing with the guys for so long and knowing that each song is going to be different. I have to have my chops up and be ready for them to switch on me pretty quickly. But it’s just whatever fits the song. Plus, I work on opinions, you know? I’ve got the three guys in the band and the producer, who all have opinions. I work on a whole bunch of different stuff, and sometimes it doesn’t work out. Sometimes I have to revisit songs because I just can’t find anything. Then sometimes they’ll say, “Yeah, that works—that should be in the song.” “Beautiful War” is one of those songs we were having a tough time with, because it kind of lends itself to the big, reverb-y sound. But I was, like, “I don’t want to do that, because that’s what people would expect.” So we tried that thing that kind of reminds me of Stevie Ray [Vaughan]. I’ll hit one note and think, “That’s reminiscent of ‘Lenny.’”

How often do you have to push Nathan or Jared or Caleb—and how often do they push you?

It comes down to when we’re actually getting the arrangement together, and we’re minutes or seconds way from recording it for the first time. There is definitely a push. I always push to make the songs more versatile and to have more interesting little parts—interesting bridges that are cool breaks from verses and choruses. I think that was the toughest part on this album—trying to convince the guys to do the breakdown on “Temple,” for example. It took a while in the studio for them to go, “Yeah, we should do that.” They challenge me a lot, too, like when it’s time for me to lay down a solo. I remember Caleb was wasted one night and screaming at me to try to get me pumped up and just making me feel really uncomfortable to the point of, like, “Dude, I’m not gonna get this done unless you leave.”

because that’s what people would expect.’”

What’s the guitar interplay like between you and Caleb?

It’s great. I told him at the beginning of this record that I wanted our parts to kind of marry, and “Comeback Story” is a great example of that. He’s playing the bassy notes—the full chordal notes—and I’m playing the lead, which is kind of the same part, but it sounds like an orchestra guitar or something. He’s definitely a different kind of rhythm player—he almost goes lead sometimes, like on “Tonight.” I think it’s pretty awesome.

How do you see the band going forward?

We’re going to tour all next year, and we’re really excited. It’s going to be tough though, because we’ve got so many songs. We made the decision a couple of weeks back that we’re going to start playing two-hour sets. It was either that or kick out songs that everybody likes, and we’re not going to have people go to a show and not be able to hear the song they want to hear. After that we’ll see how it goes. We’re either going to go straight back in 2015 to make another album, or there’s the possibility of taking another year off. It worked so well for us this last time, you know? Everything was fun and fresh, and we actually wanted to do it, as opposed to the label just telling us, “You need to make another album.” We’re great, man. We’re ready to rock.

YouTube It

To see Kings of Leon reclaim the stage post hiatus, check out the following clip:

The Followills perform “Supersoaker,” the lead single off this year’s Mechanical Bull,at O2 Shepherd’s Bush Empire in London.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.