We all know the usual reasons used and vintage guitar prices fluctuate: The overall economy obviously has a huge impact, as do new and different musical trends or buyers assigning more importance to changed tuners or refinishing. Then there’s the chance that the latest hot artist chooses to tour with your favorite guitar model, making you wish you’d bought one last year.

But a different trend has begun to impact guitar values in the last few years, and this modifier has nothing to do with music, and, in fact, has nothing to do with what guitars cost or even what condition they’re in. Instead, it’s the materials used when the guitar was manufactured that are coming under new scrutiny.

It all began back in 1975 when CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) first went into effect. This new international agreement—an organized and legislated awareness of endangered plant and animal species—didn’t have much impact on guitars initially. However, in 1992, Brazilian rosewood became a protected species that could only be legally shipped from Brazil if accompanied by a CITES export permit. Brazilian rosewood that was already in other countries, however, was still legal and more Brazilian rosewood continued to be brought to the U.S. as demand for sets of backs and sides, and boards large enough to yield fretboards and bridges, forced prices ever higher. (Most, if not all, American guitar-making companies still offered Brazilian rosewood limited editions or as an expensive option for custom orders.)

Some of these recent shipments of rosewood had paperwork, while many did not. But even when a shipment was fully legal and had the proper documentation, the paperwork rarely followed every piece of wood as it was dispersed to dozens of guitarmakers, from huge companies to one-man shops.

This issue of paperwork rarely came up in the 1990s and even through the first years of the new century, as the focus was on restricting shipments of illegally harvested raw wood with little attention being paid to the finished product. Thin Brazilian rosewood headstock veneers, for instance, continued to adorn the necks of thousands of new acoustic guitars, even though most buyers of those instruments didn’t know or care what wood they were staring at when they changed their strings.

In retrospect, we now can see trouble brewing because while there was lots of Brazilian rosewood stockpiled in North America and Europe, only a small fraction of it had documentation suggesting it was legal. And, since raw wood lacks fingerprints or serial numbers, bridging the gap from a legally imported Brazilian rosewood board to a completed guitar is iffy at best.

The question, “What rosewood is it and when was the tree cut down?” first came up at international borders, but of course customs officials for different countries aren’t always in sync. This meant you might have no trouble flying with your 1998 Brazilian rosewood Collings D2H to Vancouver, British Columbia, but getting that same guitar back across the border into the U.S. might be tricky or even impossible. Even if your Brazilian rosewood Martin HD-28BLE has a clear serial number dating the instrument to 1990 (two years before the CITES ban), customs officials don’t have a Martin serial-number dating list. Do you want to risk selling and shipping it to a bluegrass guitar fan in Germany?

Brazilian rosewood certainly isn’t the only endangered species on the CITES list. Elephants and ivory from their tusks didn’t seem to be a concern for guitar players, or those who bought and sold guitars, because nobody in North America had used much ivory in the last 40 years. In recent decades, there has been only a small amount of trade in ivory—usually for restorations—as everyone was far more comfortable with fossilized mammoth ivory. Those special bridge pins for your Custom Shop Martin, for instance, were easy to enjoy guilt-free since the species that contributed the material had long been extinct. Of course everyone knew there were tens of thousands of old and used guitars out there that had been made with Brazilian rosewood, plus ivory parts such as nuts and saddles, but that was long ago, and the use of ivory seemed to have faded along with proclaiming that you could only get good tone by playing with a tortoiseshell pick.

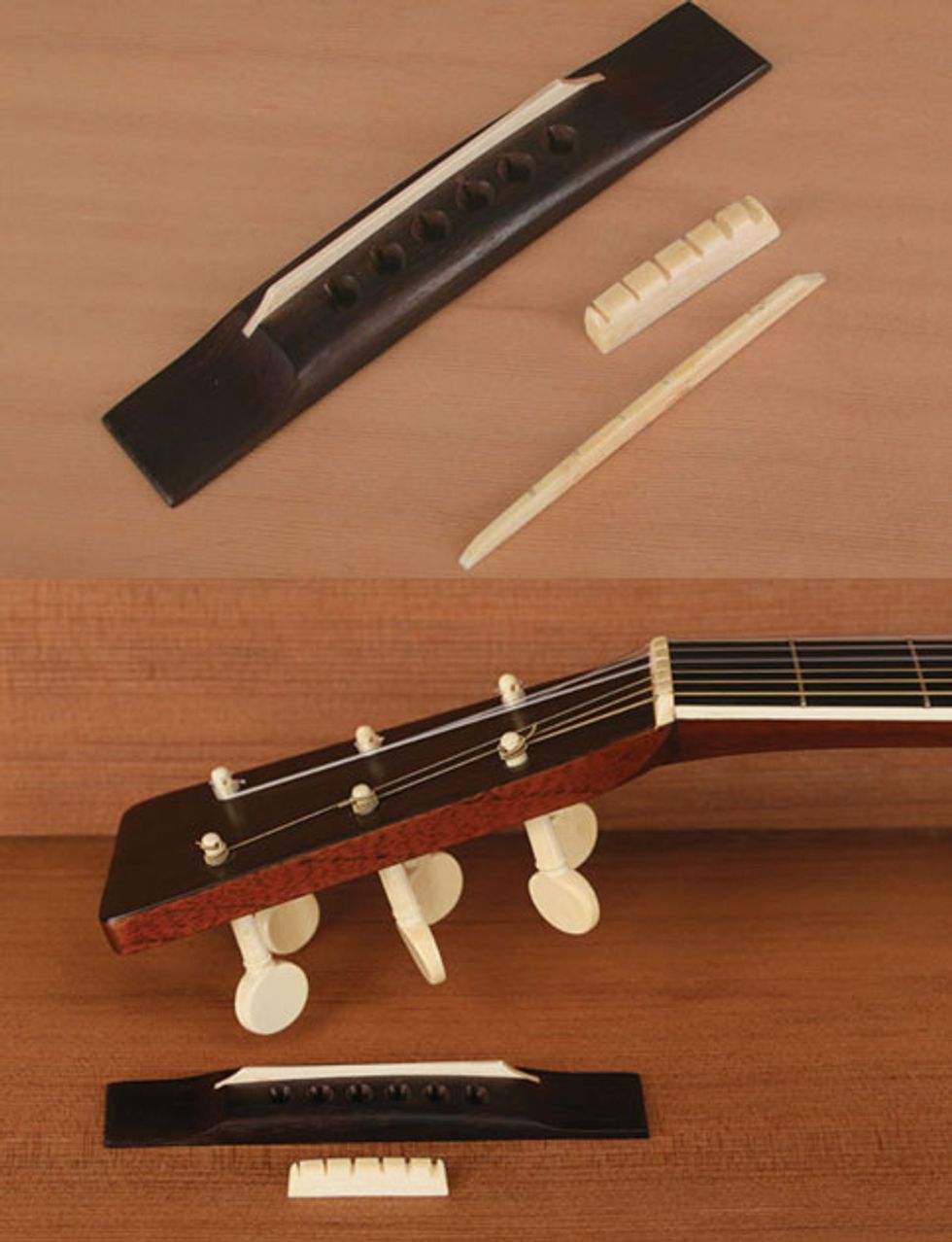

The 1901 Martin 0-34 shown here reveals how much ivory was used on that company’s higher models, as not only are the tuning pegs and bridge made of ivory, but all the binding as well. In contrast, the ivory saddle and nut show the maximum amount of ivory found on any Martin guitar made after 1920 and weigh less than 1/5 of an ounce. But that’s still enough to make the instrument illegal to sell in some U.S. jurisdictions, if recently enacted laws are fully enforced. Fortunately, the original nut and saddle can be removed and replaced with domestic cattle bone with no loss to the

guitar’s sound or playability. Photos by Grant Groberg.

But the “long ago” case for ivory took on a hollow ring by 2013 when headline news reported a dramatic rise in ivory poaching in Africa, resulting in the horrific slaughter of elephants. Illegally downed trees and stripped landscapes are one thing, but photos of slaughtered animals provoke a heightened level of outrage. Despite the fact that most poached ivory was headed for countries in Asia where it’s far more highly prized, suddenly the sale of anything made with ivory, no matter how old, was seen as related to poaching elephants. Protecting live elephants was no longer enough, and there was a growing sentiment that to squash the demand for poached tusks, the sale of any ivory needed to be banned.

Thus began a round-robin of laws with draconian penalties for ivory commerce, both on the national and state levels. The policy regarding the sale of items made with endangered species had been that items over 100 years old were certified “antiques” and therefore immune from sale restrictions. But because of the highly emotional ivory situation and new legislation, pieces 1,000 years old will soon be illegal to sell in the state of New Jersey. This means a Hackensack folkie could still inherit and play her great-grandmother’s 1890s mandolin with original ivory bindings and tortoiseshell pickguard, but selling it could land her in serious trouble. It’s almost like a “reverse grandfather clause” that turns the market for antique instruments on its head.

New rules and regulations that impact the sale and shipment of musical instruments containing materials like ivory are perhaps one of the more troubling examples of a disconnect between a newly defined illegality and any hope of enforcing it fairly. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service—which is in charge of enforcing these new restrictions regarding the sale of items containing material from endangered species—until recently hadn’t a clue how many older violin bows had ivory tips, for instance, or how many guitars made before the 1970s had ivory nuts and saddles. To complicate matters even more, ivory used as a structural element—such as a bridge saddle—can be very difficult to differentiate from bone, or from a synthetic material designed to look like ivory.

There’s some small comfort in noting that these new laws are focused on the sale of ivory, or to restrict traveling with it across international borders. There’s no indication that playing a 1955 Martin 000-28 at an open mic will land you in jail or that fiddling with an ivory-tipped bow will bring jackboots stomping through square dancers to confront the band. Yet there’s no denying that the recent changes in the government’s attitude regarding both plant and animal products used to manufacture musical instruments has many musicians wondering when the next endangered shoe will drop.

Mother-of-pearl fretboard dots, for instance, are still legal. But since they are an animal product, technically they will soon need a permit from the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service if shipped across the border. And, like most permits, it will require a fee. (Even more daunting: South American mahogany, a wood used on a majority of acoustic guitars made in North America, could be on the list of restricted woods in the future.)

Many of these regulations are still in flux and not specifically cited here (the exception is the recently signed law in New Jersey focusing on ivory). Some of these rules may change in the future, but as any stockbroker will attest, markets dislike uncertainty and the market for used and vintage musical instruments is no exception. Collectors will be the first to shy away from guitars that may be difficult to sell locally, let alone on the world market, but even musicians will probably wonder if they want to bother filling out permit applications to play a gig in Toronto.

Instrument manufacturers have already responded: Taylor has many new guitar models with no inlays made of shell (an animal product) and Paul Reed Smith has eliminated the use of any questionable species from most of its electric guitar production. And for a musician about to embark on a world tour, new instruments made with synthetic materials that signal being man-made at first glance may have new appeal.