“Loose lips sink ships.” During the Second World War, this phrase reminded American citizens to be careful about mentioning sensitive information. A carelessly spoken reference to a freight shipment or a serviceman’s whereabouts might result in a torpedoed vessel or bombed village. This directive was also scrawled on a poster in the office of Northern Prairie Music—our vintage-guitar shop just north of Chicago.

In our case, it referred to divulging “trade secrets,” or the whereabouts of desirable instruments. The wartime mentality of the greatest generation had been passed down to baby boomers who employed it as a business tool. The “we’re all in this together” attitude had morphed into a misguided individualism that viewed business (and life) as a zero-sum game. I’ve since realized this worldview is paranoid, narrow, and soul crushing. For me, the build is a journey and the player is the point. I love the way guitarists have taken to the idea of custom-built brands and have come to enjoy the community of individual builders. Still, I wonder if the proliferation of small-batch guitar makers isn’t at a tipping point where the “you lose, therefore I win” game-theory philosophy rings true as prophecy.

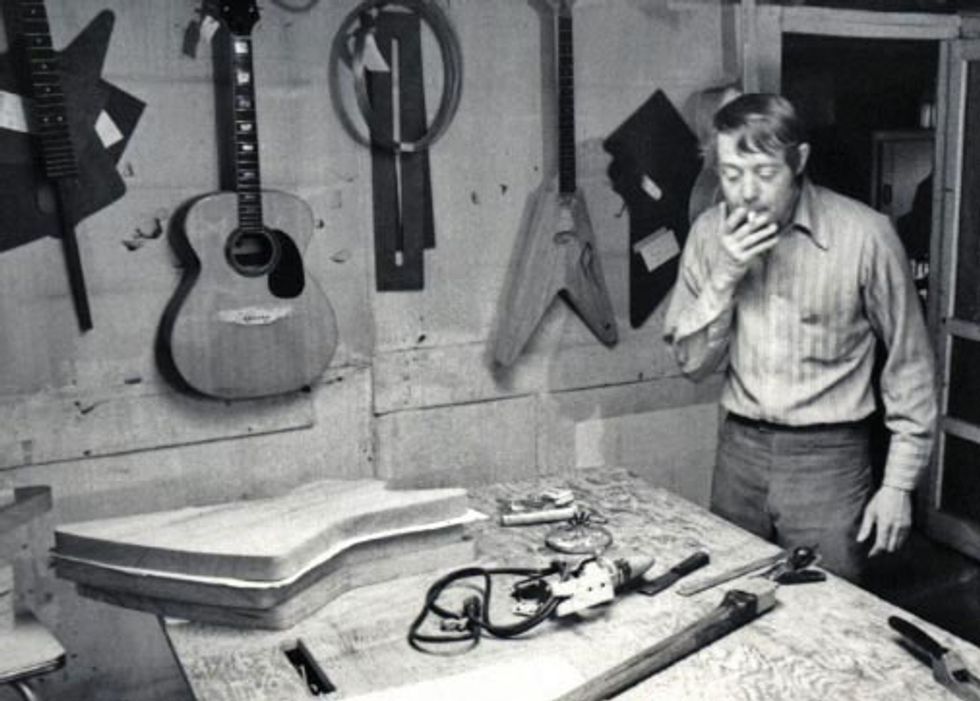

When I began making guitars in the early 1970s, there were only a handful of guitar builders whose reputations reached beyond their own cities or towns. John D’Angelico, Doug Irwin, and Michael Gurian spring to mind. My interest in guitar making was piqued because my daily walk to work took me past Richard Bruné’s small luthiery shop. I ventured inside to talk to him and marvel at his workshop full of wood and tools. The idea that one person could create a classical guitar, let alone make it his paying job, blew my mind. And it sowed the seed that I could make an instrument of my own. I didn’t want to get rich. I just wanted to build a cool guitar.

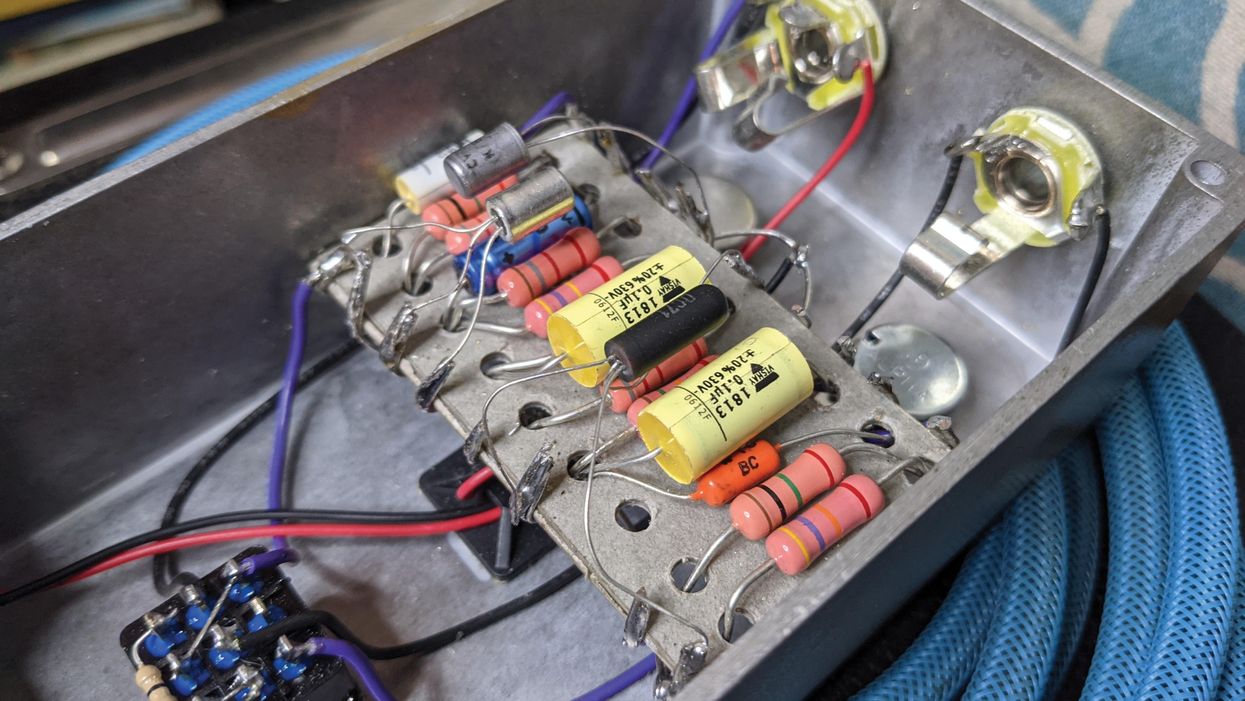

Later, I worked at Music Dealer Service in Chicago, a warranty service station utilized by music stores in a 75-mile radius. I started out driving the delivery truck, but I stuck my nose into everything and asked lots of questions. I did grunt work like replacing speakers in cabinets, stripping guitars, pulling circuit boards, and gluing Tolex on cabinets—not a pleasurable high. By the time Paul Hamer and I were partners in Northern Prairie, I had amassed a fair amount of disparate knowledge, but we didn’t imagine we could make guitars.

Eventually I met two pivotal figures: John Montgomery and Jim Beach. Montgomery worked at another music store and did repairs on the side in the basement of his home. Beach owned a guitar shop on Lincoln Avenue in Chicago called Wooden Music, and did repairs and made his own guitars. Because our own shop didn’t have the tools and equipment needed, the idea of subcontracting was very appealing. Beach could do the woodworking, Montgomery would do the finishing, and I could do the assembly and setup. It was small-time, but it was fun. The best part was that I got my dream guitar.

We were lucky to be in the right place at the right time. Our vintage-guitar clientele were the top players and biggest acts in music, and it was only natural that we also offer them the vintage-inspired guitars we made. Before the internet came along, our little brand went viral and there wasn’t much competition. There was plenty of room for another brand. Eventually, we built a small factory. It still wasn’t about the money for me, but things got a lot more serious. Our fledgling business grew up and we made tens of thousands of guitars.

So, what does my career path have to do with the craft-brewing-like guitar industry of today? A quick scan of boutique guitar listings reveals somewhere north of 500 builders beginning with the letter “A” alone. The proliferation of guitar building has turned the industry into a zero-sum game of sorts after all. The pie gets sliced up into smaller and smaller pieces. I have the fortune of a 40-plus-year reputation, plenty of business, and no aspirations to grow large. People like Tom Anderson, John Suhr, and the late Bill Collings persevered as bigger players in the ever-more-crowded smaller pond.

How much business the basement shops have cannibalized is anybody’s guess. Every town has someone making guitars in their garage, and more than a few families have bet the farm on the hobby. I often wonder if it is sustainable for them, or for the industry. In the meantime, it’s a great time to buy a custom, small-batch guitar—while it lasts.