Well, that didn’t feel like two years, did it?

When I proposed the Subversive Guitarist column to my Premier Guitar pals in 2018, we figured on 20 or so installments, to be followed by a book version of the series. For once, things went precisely as planned: This is the final column in the series, and PG will issue a book version (with lots of extra material!) later this year. Meanwhile, I’m not going anywhere. I’ll continue to float around the PG universe, and I’ll be part of a cool new ongoing project to be announced soon.

I can’t summarize every Subversive Guitarist column here. But I’ll recap some key concepts, with one goal in mind: creating an ongoing series of mental, technical, and musical challenges to keep your playing moving forward. That’s what I mean by “perpetual subversion.”

Breaking Boxes

As stated upfront in the

first column, this series was inspired by the most common complaint I hear from intermediate and advanced

players: “I feel like I play the same things every time I pick up a guitar.”

I believe that’s because most of us learn using the same licks, formulas, and box patterns. Those tools help make guitar a relatively easy instrument to learn. The downside is, that stuff can get baked in as muscle memory. Your hands automatically fall into their familiar patterns.

Every exercise in this series aimed to subvert this cycle. But the point isn’t the individual exercises so much as the processes behind them. You can apply these endlessly, perpetually challenging yourself and uncovering new ideas.

Comfortable Techniques in Uncomfortable Places

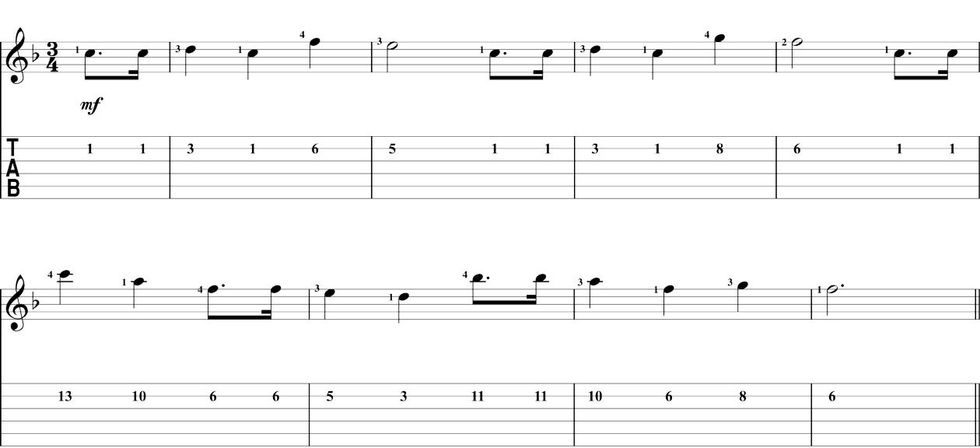

One useful procedure is to apply a technique systematically to every note or chord in a musical passage. Take

position shifts, for example: We tend execute them favoring certain fingers, positions, and strings, especially when

improvising using box patterns and scales. But picking out melodies by ear using only a single string (suggested in

the July

2018 installment) undermines those habits. With practice, you can get comfortable shifting positions by any

interval using any finger, all while honing your ability to play melodies by ear. We used “Happy

Birthday” as an example (Ex. 1). Why not just attempt a single-string version of some random

melody as part of each practice session?

Going to Extremes

It can be revealing and inspiring to apply techniques in a more extreme fashion than we might during regular

playing. We did that when we focused on sliding between notes in the Dec.

2018 column. Ordinarily, we tend to favor particular fingers, positions, and beats when using this

technique. But if you apply the technique systematically to every note in a melody, you can break out of your usual

habits, cultivating freer and more flexible phrasing. The examples used the cowboy ballad “The Streets of

Laredo.” We started by learning the basic melody in Ex. 2.

Click here for Ex. 2

Next, we replayed the melody, sliding into every downbeat note (Ex. 3). Then sliding into the second beat of each measure (Ex. 4), and then the third beat of each measure (Ex. 5).

And then we did it all again but sliding down into each note. Try this with the first tune that pops into your head.

Another exercise in extremes was when we exploited the guitar’s maximum dynamic range in the June 2019 installment. We tried to play using 10 distinct volume levels ranging from barely audible to the loudest possible attack (Ex. 6).

Click here for Ex. 6

We all have a general sense of when to play louder and softer. But practice using the instrument’s maximum range and exploiting subtle dynamic changes can bring greater mindfulness, control, and expression to your playing.

Melodic Disruption

We’ve all got favorite phrases we like to play. It’s part of what defines our personal style! But

sometimes our lines are nothing more than muscle memory on display. Exercises that force you out of your familiar

fingerings are an excellent remedy.

For example, many of us practice scales—a good thing! But you can benefit far more from the exercise if you venture beyond simply running them up and down using only adjacent notes. We did that in the April 2019 lesson, where we tried practicing scales using short melodic “cells,” repeated on successively higher or lower scale steps, as in Ex. 7.

Click here for Ex. 7

That way, you eventually practice every possible intervallic leap, not just the familiar ones. The benefits are finding new melodies, getting better at playing tunes by ear, and general mindfulness. If you select a different short melody to play sequentially each time you practice scales, you’ll benefit far more from the exercise.

We tried another “scale disrupter” in the July 2019 column: octave leaps. Moving fluidly between octaves can create generate more interesting melodies while honing fretting-hand speed and accuracy. We practiced skipping octaves at shorter and shorter intervals, culminating in Ex. 8. It’s “The Streets of Laredo” again, but with an octave shift occurring between every single note.

Click here for Ex. 8

Composite Rhythms

We looked at various ways to expand you your rhythmic confidence and creativity, but it all boiled down to two

techniques: composite rhythm and rhythmic displacement.

Composite rhythm pertains to hearing the multiple rhythms in a piece of music not as isolated entities, but as parts in a single organized tapestry. That can be as simple as confidently tapping a foot while playing rhythms whose rhythms don’t coincide with the taps, as in Ex. 9.

Click here for Ex. 9

Then we got trickier, tapping rhythms other than the downbeat while playing syncopated rhythms, as in Ex. 10.

Click here for Ex. 10

This can be a humbling exercise, especially when you remember that drummers do more difficult things every time they play.

Rhythmic Displacement

We also talked a lot about cultivating the ability to shift rhythms in time—a technique that’s far

easier to describe than execute. One way to tackle it is by studying famous guitar intros that deceive you into

perceiving the downbeat as somewhere other than it is, only to surprise you when the full band kicks in. Ex.

11 is one of the examples from the

August 2019 column.

Click here for Ex. 11

We revisited the notion in February 2020 column, where we started with a common folk fingerpicking pattern, only to shift it around to eight possible starting points within the measure, as seen in the video below.

The ability to shift parts in time on the fly can resolve countless arrangement problems and help you craft groovier, more interesting parts. It’s all about making the familiar unfamiliar. Hey, that’s worth saying twice!

Making the Familiar Unfamiliar

Want to generate new ideas and cultivate new skills every time you practice? Then always be sure to practice a few

strange and uncomfortable things. It can be as simple as playing a familiar scale using new melodic sequences. Or

always substituting new chords each time you practice a fingerpicking pattern. Or shifting a part in time by a 16th

note. Or flipping an exercise backward and playing it start to finish. The possibilities are almost practically

endless.

With an attitude like this, you’ll never cross the finish line—and that’s great! Guitar becomes a lifelong challenge, always fresh, always fascinating. And you’ll never again have to say, “I feel like I play the same things every time I pick up a guitar.”