Chops: Intermediate

Theory: Intermediate

Lesson Overview:

• Create rhythmically interesting

comping patterns.

• Learn how to use syncopation.

• Develop a more “conversational”

approach to rhythm playing.

To me, the guitar is one of the greatest instruments of all time. Not only is it beautiful as a music-producing machine, but also the variety of sounds that can be made from a single guitar are beyond comprehension. A guitar can play the role of a lead voice effortlessly, sounding like the most natural thing you’ve ever heard. It can also turn on a dime and be the ideal instrument for accompaniment. In this lesson, I’d like to focus on the latter role and explore how to develop your own personal concept of accompaniment—or “comping,” as it’s known in jazz—from the perspective of rhythm first, and then harmony.

Let’s begin by defining what it means to comp. In jazz, the role of the accompanist is to essentially bridge the gap between the rhythmic and groove-oriented world of the bassist and drummer with the harmonic and melodic world of the soloist. Simply put, it’s up to us to connect the dots, all while striking a balance between giving soloists space to create a melodic narrative and pushing them towards new heights with harmonic and rhythmic commentary. At its core, comping is a social activity. It can be equated to being a moderator on a panel discussion. You have the bird’s-eye view of everything that’s going on and have the power to direct the listener’s attention to any aspect of the unfolding music that moves you.

The responsibilities of a good accompanist are more or less consistent. However, it is important to address a difference I’ve noticed between musicians who are good at comping and those who are especially great at it. Lesser-experienced guitarists will usually define, albeit quite unconsciously, their role as someone who lays down the chords to keep the form clear and to show the soloist where they are in the song at any given moment. Though this can be absolutely essential and effective, it can get you in trouble when you’re playing with more experienced soloists or rhythm sections. These musicians are already completely clear on the form and don’t need the chords to be outlined so rigidly. In such scenarios, great accompanists will relinquish the responsibility of only defining the form and time feel, and will instead use comping as a means of adding rhythmic and harmonic color to the music. It’s through this approach that comping becomes really exciting and truly interactive. All of a sudden it becomes important that your comping has a melodic and architectural contour. Ideally, it should be as integrative and intriguing as the solo being played. When this is done at the highest level, it can lift the music to new heights.

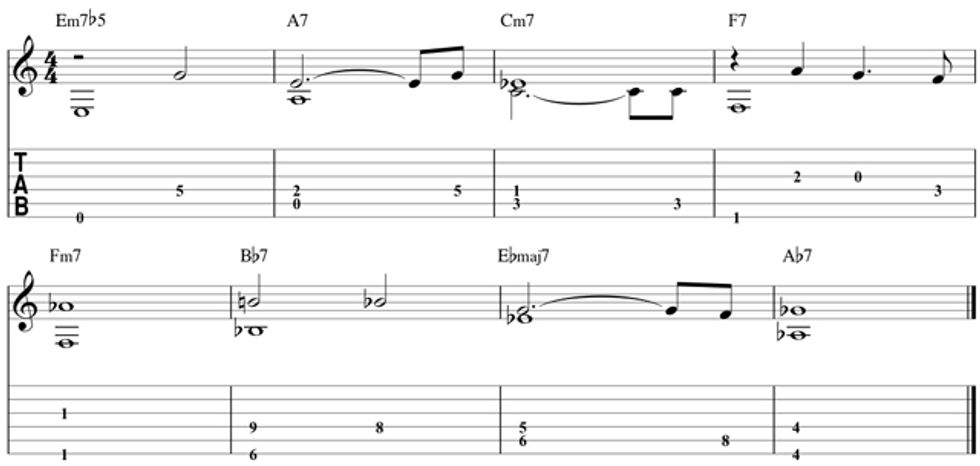

So let’s explore how to go about practicing this approach. One of the best ways to work on the subsequent examples is to start by recording a simple bass line for a song of your choice (just the roots played in half-notes), then record a solo on another track, and then go back and practice comping along with your solo. This will help simulate a real-life comping situation, but with the benefits of it being a controlled environment.So often, we are taught that the road to great comping lies in learning hip voicings. Although an expanded harmonic toolkit is important in order to be an effective commentator, having an intimate relationship with the rhythmic side of things reigns king. In order to practice this, let’s take a harmonic progression and rather than using full chords, start by comping with one note at a time, played only on one string—in this case, the 4th string. By limiting ourselves harmonically, we’re forced to focus more on the rhythmic integrity of our accompaniment. As far as harmonic content, let’s begin by playing notes that can be found in the scales associated with each chord, mainly focusing on chord tones such as the 3rd, 7th, or 5th, to help clarify the harmonic motion that underlies the progression. With a simplified, one-string, harmonic concept in place, it’s time to start practicing rhythmic variety, beginning with relatively simple phrases and working our way up to more complex syncopation.

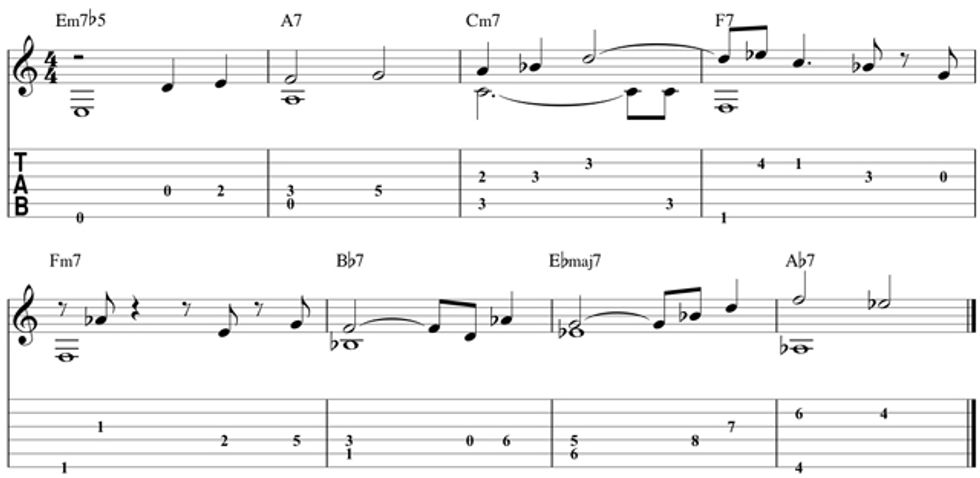

In Fig. 1, we focus on long tones with occasional passing tones in order to basically provide a countermelody. From a rhythmic point of view, we are embellishing the bass line, as well as the hi-hat. You can think of this first stage as representing the harmonic equivalent of the drummer’s ride cymbal. This can produce an echo effect to the solo, much like the way a viola line in an orchestral piece might play a melody that weaves around the main theme played by the violins. From a conversational point of view, this is akin to having a conversation with someone who more or less agrees with everything your saying, but occasionally offers an insight on the topic that wasn’t totally obvious to you.

Next, let’s add some more syncopation. One of the most effective tools at your disposal is the use of sustained and staccato attacks. The conversation between the two can often create a wonderful sense of forward movement, and furthermore symbolize the marriage between the staccato feel of the snare drum with the sustained characteristics of the cymbals. Syncopation is often most effective when it is thought of in the context of a larger phrase. It can work well to visualize all of your comping in four, eight, or six measure chunks—or any length for that matter. If you are playing a 32-measure song, you can simplify it by envisioning eight sections of four measures, or four sections of eight measures. This will help to keep a structural and thematic through-line in your comping, and allow you to avoid always sounding like you are jumping on each syncopated idea played by the soloist. In conversation, this is similar to the difference between speaking to someone who interrupts you to tell you they know what you are talking about, versus speaking with someone who listens intently to everything you have to say and then when a pause arises, offers their response. See Fig. 2 for an illustration of this kind of phrase-based comping.

Finally, let’s begin to add a second note to our single-line comping in Fig. 3. However, rather than adding it for harmonic variety, we will only be adding the octave, so as to explore the concept of density in comping. In any given accompaniment scenario, two of the most important tools at your disposal are the use of dynamics, as well as density. We’ve already seen the effect of increased rhythmic density through the use of syncopation, but let’s now explore alternating between one- and two-note comping, all while maintaining a steady rhythmic narrative. For me, the power of this is being able to play dense rhythmic passages using single notes with the ability to reinforce simpler passages by adding the octave. It’s possible for a really intriguing and supportive accompaniment to emerge by alternating between these two approaches.

From a conversationalist point of view, this could be analogous to having a conversation with a whole group of people, all with different yet mutually supportive viewpoints. Rather than putting the pressure on one person to respond and interact with you, you are essentially providing the soloist with a whole community of voices to interact with. When executed well, this elegant transition between different timbres and varying degrees of density provide an incredibly interesting and thoughtful through-line in one’s accompaniment. This approach supports the main attraction and keeps you from playing a mere background part.

Eventually, after practicing these techniques for a little while, you will quite naturally want to expand upon the harmonic side of comping. In future lessons, we will explore how to become acclimated to a wider array of harmonic shapes and structures on the guitar, so you don’t feel trapped by having to play chords that always begin on the root. In the meantime, practice comping with an ear towards rhythmic propulsion and enjoy exploring all the ways you can make the music come alive.

Julian Lage is one of those rare musicians who feels equally at home in acoustic and jazz cir- cles. He has been a member of legendary vibra- phonist Gary Burton’s group since 2004, and also regularly collaborates with pianist Taylor Eigsti. Lage’s latest album, Gladwell, reflects

his wide-ranging musical interests and talents by incorporating chamber music, American folk and bluegrass, Latin and world music, tradi- tional string-band sounds, and modern jazz. For more information visit julianlage.com.

Julian Lage is one of those rare musicians who feels equally at home in acoustic and jazz cir- cles. He has been a member of legendary vibra- phonist Gary Burton’s group since 2004, and also regularly collaborates with pianist Taylor Eigsti. Lage’s latest album, Gladwell, reflects

his wide-ranging musical interests and talents by incorporating chamber music, American folk and bluegrass, Latin and world music, tradi- tional string-band sounds, and modern jazz. For more information visit julianlage.com.