We’re in the process of exploring

ways to make three-note voicings

sound bigger than typical triads. In our

first installment of this three-part series

(“Hybrid-Picking Pals,” January 2011 PG),

we took the middle note of a root-3rd-5th

triad and lowered it an octave to expand

the chord’s component intervals. This simple

technique converts a triad that occupies

a single octave (a close-voiced triad) to one

that spans more than an octave (an open-voiced

triad).

When you’re alternating between a hybrid,

flatpick-plus-two-fingers technique and full-on

strumming, the trick is to balance the

sound of plucked three-note grips against the

jangle of strummed five- and six-note chords.

Because open triads claim a larger sonic territory

than their close-voiced siblings, they

hang better with strummed chords.

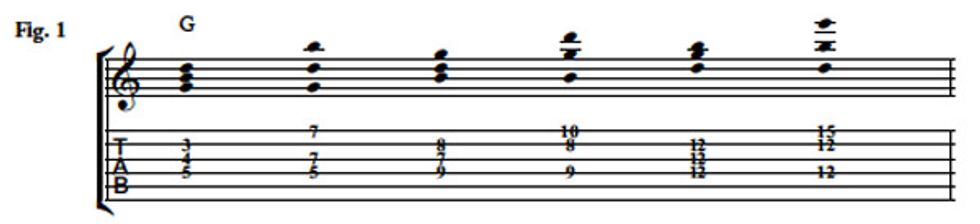

Let’s hear what happens when we take the

middle note of a close triad and raise it an

octave. Fig. 1 begins with a root-3rd-5th G

major triad. By moving B, the middle tone,

up an octave, we get the second chord—an

open G triad that’s voiced root-5th-3rd. This

voicing has a cool, spangly sound. Download example audio 1...

Staying on the same string set, we shift up the fretboard to play a 1st inversion G triad (3rd-5th-root) in both close and open forms. Notice how the open triad rings more, thanks to its larger intervals. Finally, we move up the fretboard again to play a 2nd inversion G (5th-root-3rd), first as a close triad, then as an open one.

Fig. 2 repeats the process with a Gm triad. As you play through these voicings, listen closely and compare the close and open structures. Take time to visualize the octave jump—watch that middle note and track its movement on the fretboard. Download example audio 2...

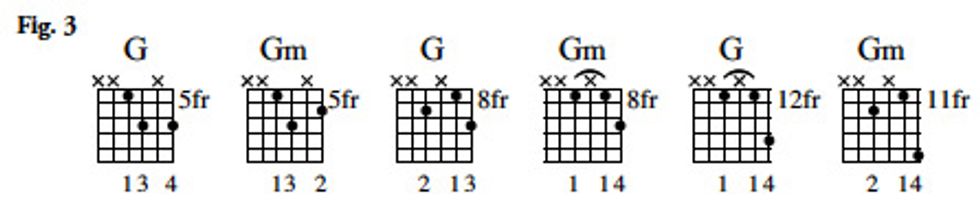

In Fig. 3, we strip out the close triads from our previous examples to focus on the fruits of our labor: three pairs of open major and minor triads. Because they don’t use open strings, these forms are moveable, which means you now have dozens of new chords at your fingertips. To claim them, simply slide these grips up and down their respective strings, keeping an eye on the root and calling out each chord’s name as you pluck it. Download example audio 3...

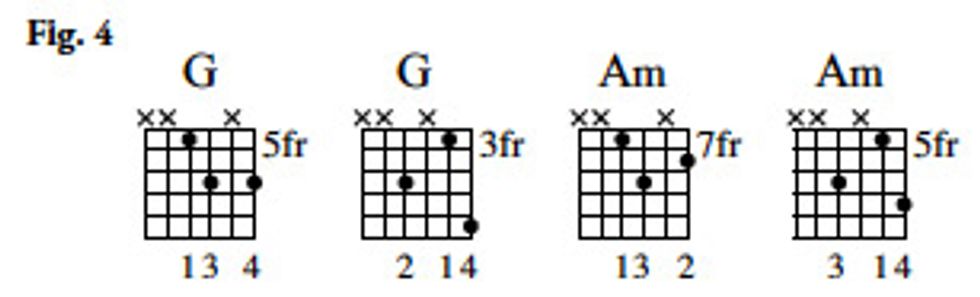

Open-voiced chords can be slippery little buggers, as shown in Fig. 4. When you play the two G chords, for example, you’ll see they contain the same chord tones, despite the change in fingering and string set. (For tips on how to handle the alternate grip, see “Setting Up the Five-Fret Stretch” above.) There’s a subtle timbral transformation caused by the D migrating from the 3rd string to the 2nd, but the pitches themselves are identical: G–D–B. This also holds true for the two Am forms—same pitches, different strings and fingering. Download example audio 4...

Fig. 5 illustrates why it’s handy to know alternative fingerings for the same open-voiced triad. If you look carefully at bar 1, you’ll see that by using the alternative Am grip, you get to stay in the 5th position while shifting from G to Am. The Csus4 in bar 2 proves you can momentarily substitute the 4th for the 3rd in an open triad— the same way you can with a close triad— to create harmonic tension and release. Download example audio 5...

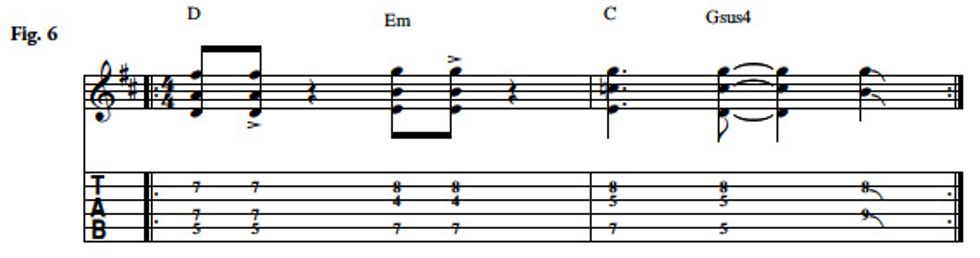

Whenever you learn a new progression, it’s a good idea to explore it in different keys and fretboard regions. One quick way to do this is to move the entire operation to a different string set. In Fig. 6, we drop our previous two-bar progression to the next lower set of strings. Yes, there’s some rhythmic variety to keep things interesting, but fundamentally, we’ve simply moved the progression down a fourth. Watch the accents in bar 1 and emphasize the slide as you come off those sixths at the end of bar 2. A little slapback echo? Yeah, that might sound nice with this example. Download example audio 6...

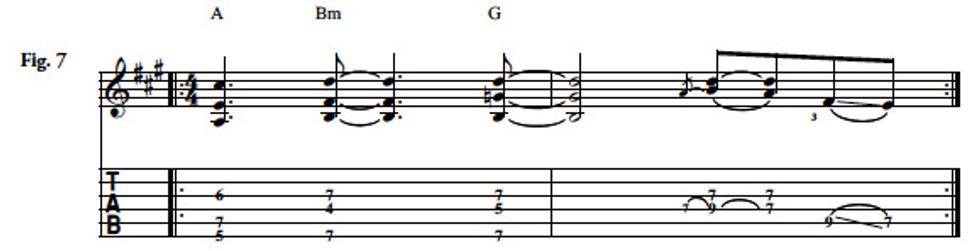

Let’s shift string sets again by dropping down a fourth one more time. Fig. 7 takes our open-voiced progression down to the lowest four strings for a wiry, dark sound. If you use your 3rd finger for the slide at the end of bar 2, you’ll be back in position for playing A again in bar 1. Smooth! Download example audio 7...

After you’ve digested these three progressions, create a few of your own by mixing and matching the open forms we’ve covered in this lesson. Next month, in our final open triad episode, we’ll look at another form we can create by moving two notes of a closed triad in opposite directions. We’ll also look for ways to mingle all the fingerings we’ve developed so far. See you then.

Setting up the Five-Fret Stretch

Tal Farlow, Merle Travis, Richie Havens, and Jimi Hendrix showed us the many wonderful ways we can use our fretting-hand thumb to grab notes on the bass strings. But there are times when this “thumb wrap” approach just doesn’t work. some open-voiced triads involve stretches of five frets, and to play them, you must firmly plant your fretting-hand thumb behind the neck.

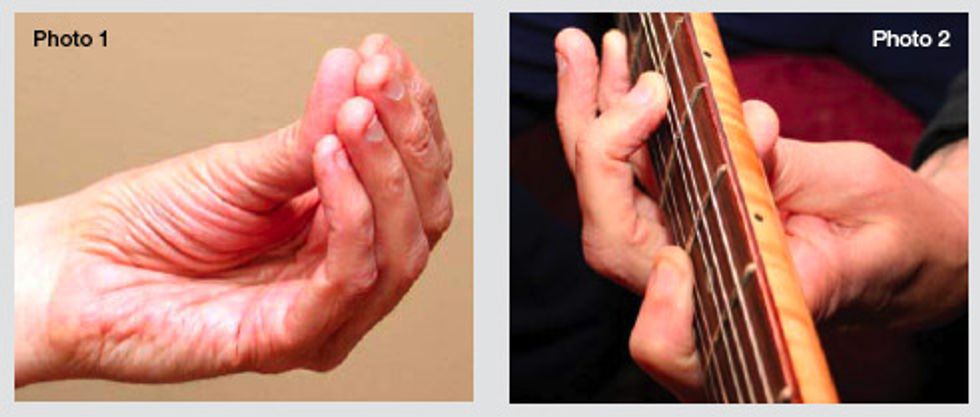

To manage big stretches, the trick is to find a position where your thumb provides both maximum strength and reach. Fortunately, that’s easy: With your fretting hand off the guitar, open your hand wide and then bring your fingers and thumb together. Stay relaxed and move slowly. when your thumb and fingers gently touch, as in Photo 1, notice the relative placement of your thumb and fingertips. everyone’s hands are a little different, but you can see that my thumb naturally closes against my first and second fingers, with the second finger resting on the center of my thumb.

Open and close your hand several times to clearly visualize how your fingers naturally come together and draw apart. Finally, open your hand again, place it around the guitar neck, and—easy now—try fretting the second G chord in Fig. 4. in Photo 2, you can see that although my fingers are spread way out, the relative positions of the thumb, first, and second fingers remains pretty much the same as when they were relaxed and resting together. this provides the optimal mix of strength and reach i need to nail the gnarly five-fret stretch. Photos by Tedra Walden

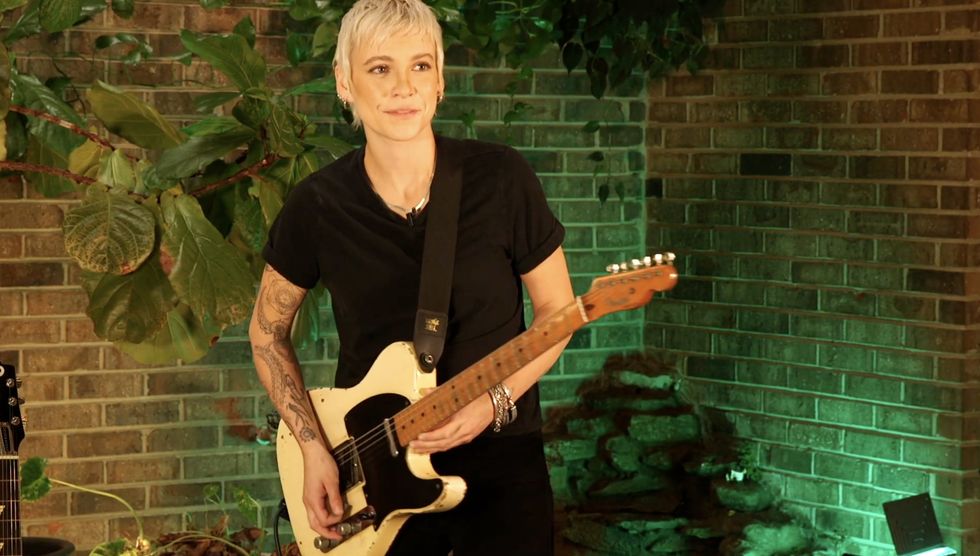

Andy Ellis is a veteran guitar journalist

and Senior Editor at PG. Based

in Nashville, Andy backs singer-songwriters

on the baritone guitar, and also

hosts The Guitar Show, a weekly on-air

and online broadcast. For the schedule,

links to the stations’ streams, archived audio

interviews with inspiring players, and more,

visit theguitarshow.com.

Andy Ellis is a veteran guitar journalist

and Senior Editor at PG. Based

in Nashville, Andy backs singer-songwriters

on the baritone guitar, and also

hosts The Guitar Show, a weekly on-air

and online broadcast. For the schedule,

links to the stations’ streams, archived audio

interviews with inspiring players, and more,

visit theguitarshow.com.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)