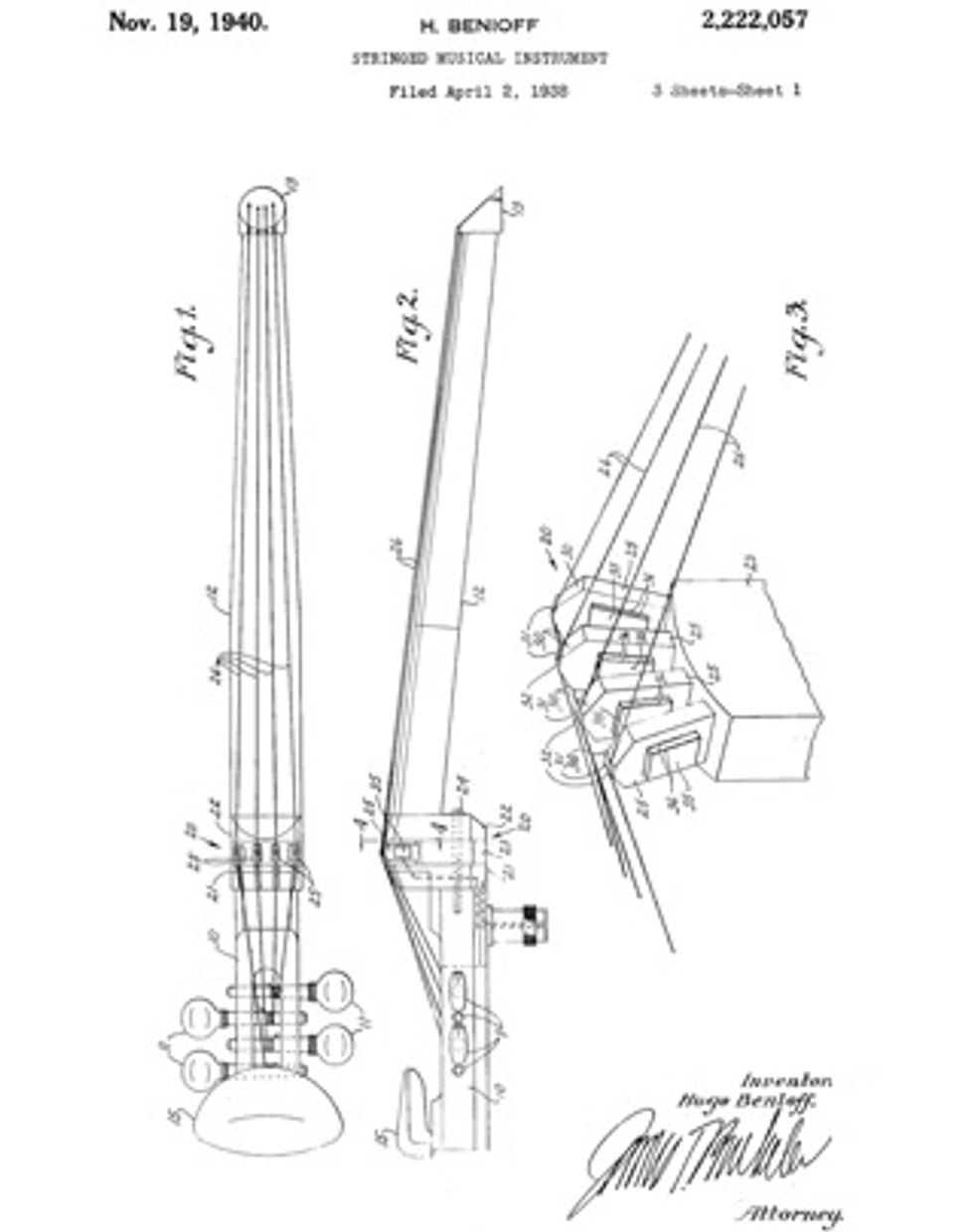

This sketch and referenced patent from 1943 for a headless, solidbody violin represents what may be the very first piezo-electric bridge transducer.

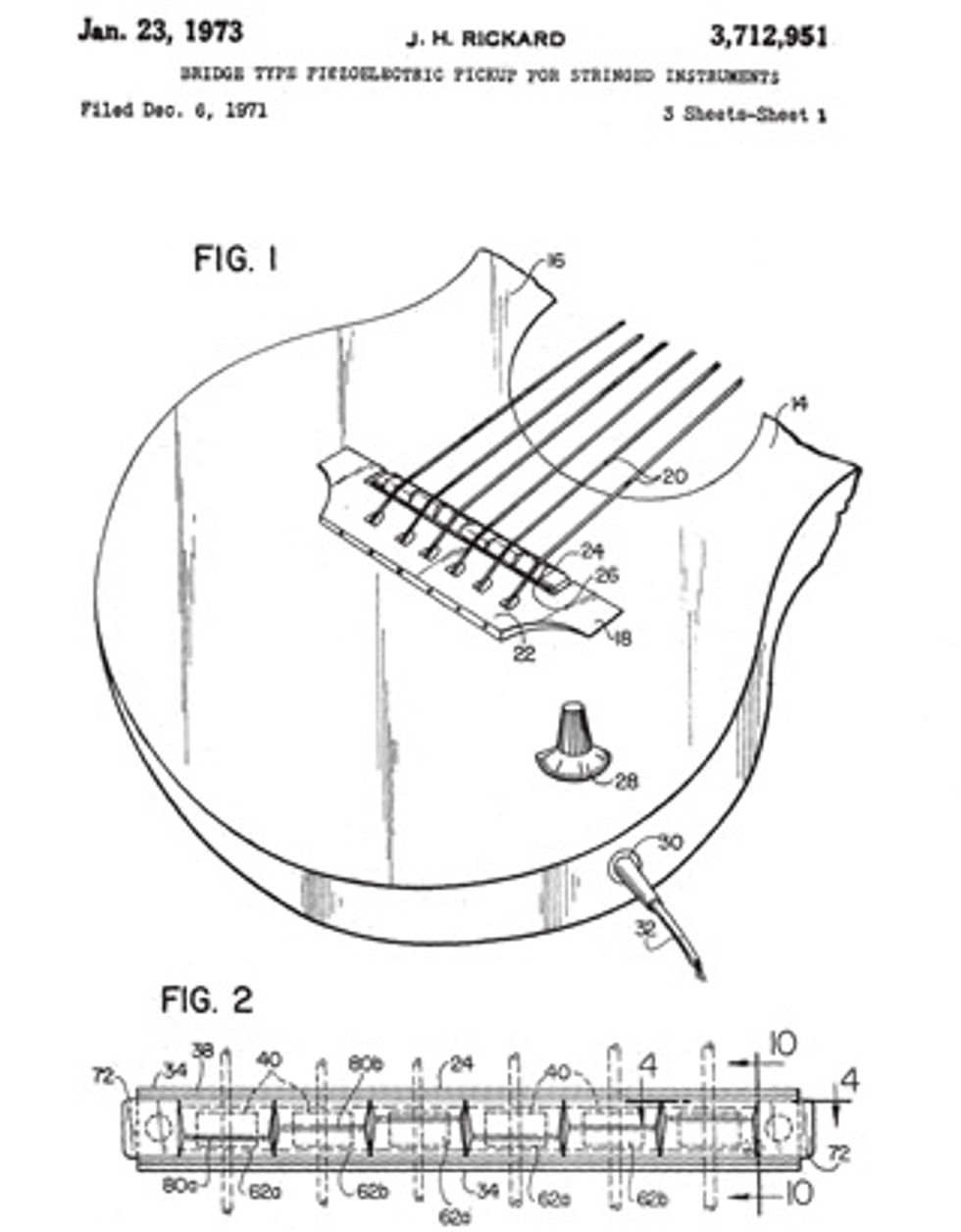

Along with a ringing endorsement from Glen Campbell, Ovation engineer Jim Rickard’s design for a piezo-equipped bridge system would help propel the new company’s popularity in the ’70s.

Over the course of my past few columns, we’ve discussed the benefits and challenges of amplifying an acoustic instrument, as well as choosing the best gear for a particular situation. As promised, we’ll now look at the specific elements in the amplification signal chain in more detail.

The signal chain actually starts with plucking a string. The mechanical energy created by this action then transfers to the instrument through the saddle mounted on the bridge. This energy “excites” the instrument’s body by making it resonate, which in turn excites the air in the room. When amplifying an acoustic instrument, the mechanical energy is captured by some sort of electromechanical device, converted to an electrical signal, and then fed to a sound-reinforcing system, such as an amp or PA, for volume enhancement. Of course, this electrical signal can also be fed into a recording device too.

Mechanical energy can be converted into electrical energy (aka transduction) by either direct or indirect methods. The indirect method is accomplished with microphones that react to the pressure changes in the air caused by the vibrating instrument. With indirect conversion, the nature of the room acoustics and other ambient artifacts (noise) have a significant effect on the ultimate electrical signal that is produced.

The direct conversion mode is realized by attaching a vibration sensor or force sensor directly to the instrument. For obvious reasons, the electrical signal produced in this mode is much more immune to room acoustics and ambient artifacts than a signal produced in the indirect mode.

In my next few columns, we’ll explore one direct-conversion device in particular— the undersaddle transducer (UST). There are many types of direct-conversion transducers for acoustic guitars, but the undersaddle variety is by far the most widely used by today’s manufactures and builders. And drilling down one step further, we will be focusing on piezo-electric undersaddle devices. While there are a few examples of non-piezo undersaddle designs, over 99 percent of the devices produced today use piezo technology.

Piezo-based saddle transducers for musical instruments have been around for quite some time. Some early uses of piezoelectric transducers for pianos show up in patent literature as early as 1931, and their use in bowed and plucked instruments would follow soon after. In fact, one of the earliest designs on record is described in a patent issued to Hugo Benioff in 1940. This patent references a headless, solidbody violin with what I believe is the first piezoelectric bridge transducer! These devices have evolved significantly in the past 30 years and a modern version of this type of instrument, designed and marketed by Ned Steinberger, has become popular with today’s plugged-in violinists.

Piezo-equipped bridge systems for acoustic instruments were beginning to be used in the early ’60s by companies like Gibson on their C1-E electric-classical guitar. The Baldwin Piano Company also produced an electric-classical model called the 801CP that was used by Jerry Reed, Glen Campbell, and Willie Nelson. A drunk destroyed Nelson’s 801CP beyond repair, but he liked the pickup so much he had it installed in “Trigger,” the famous Martin N-20 he still plays today.

When Charlie Kaman started Ovation Guitars in 1966, the company was small and just beginning to receive attention for its radical approach to guitar design. But suddenly, along came Glen Campbell. Apparently Charlie wanted Campbell to use his guitars and Campbell, who was using his Baldwin at the time, agreed to do so if they could provide him with a built-in pickup similar to Baldwin’s Prismatone. Ovation engineer Jim Rickard went to work, came up with a design, and applied for a patent that was granted in 1973. This pickup became the foundation for the entire line of Ovation acoustic-electric guitars, which would quickly gain in popularity with Campbell as an endorsee and the huge exposure he gave the company on CBS’s The Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour television show.

Suddenly, a revolution was underway: U.S. guitar manufacturers began producing a new category of guitars with built-in piezo-saddle bridges, and this revolution would continue to gain momentum throughout the ’70s with the entrance of Takamine and other Japanese manufacturers.

Chris Martin, CEO of Martin Guitars, often says the emergence of the amplified acoustic guitar actually saved the acoustic guitar industry from the disastrous condition it was in during the late ’70s and early ’80s. These new acoustic guitars could now hold their own in any venue and at any volume. Just look at the great success of modern country music, the rock ballad, the modern folk movement, progressive bluegrass, and the emergence of the Seattle music scene. And what about MTV’s wildly successful Unplugged series? None of these would have been possible without amplified acoustic guitars.

Next time, we’ll look at some of the early built-in systems in detail and find out why some worked and others didn’t.

Larry Fishman holds

more than 30 patents in

transducer and musical

instrument design. He is

president and founder

of Fishman Transducers,

which he began in his

garage in 1981. In the early ’90s, he

also co-founded and managed Parker

Guitars (which was later sold to U.S.

Music Corp.) with his friend Ken Parker.

Larry Fishman holds

more than 30 patents in

transducer and musical

instrument design. He is

president and founder

of Fishman Transducers,

which he began in his

garage in 1981. In the early ’90s, he

also co-founded and managed Parker

Guitars (which was later sold to U.S.

Music Corp.) with his friend Ken Parker.