In 1995, Jill Sobule's eponymous album included her song “I Kissed a Girl." On the 2008 album, One of the Boys, Katy Perry released a different song with the same title—and it became a smash hit. Was this fair play or song theft?

About six months ago I worked as a bandleader and music director for the 2011 Mint Jubilee, a mammoth charity gala that occurs on the eve of the Kentucky Derby. The acts we were working with were American Idol winners Jordin Sparks and Kris Allen—both wildly talented, fun, and gracious musicians. I'd not played any current pop music for a long time, so this was a welcome change from my twangy norm and a chance to catch up on what's happening in the pop and rock world. But here's what really struck me: Although these songs were fresh, hooky, and inventive, their titles were—like 75 percent of all music—derivative.

We started with Kris Allen's “Live Like We're Dying." Allen's song has a great melody, and a powerful message, but you can't help but notice that the title is clearly taken from the 2004 CMA Song of the Year recorded by Tim McGraw—“Live Like You Were Dying." With a hook like this, the title is the concept. The title demands that you not stray far from the idea of making the most of life, because it's going to end soon. (As my Italian grandfather Joseppi would say, “Memento mori," which essentially means “Remember, you will die.") Granted, the title and message were very close on the Allen and McGraw songs, but the grooves and melodies were unique and Allen's performance was fantastic.

Allen's second song, “Alright with Me," fell into a similar category. This title has been a hit for Cole Porter, George Strait, Patti Labelle, Eric Hutchinson, Tom Waits, the Zombies, and many more. Again, Allen's song, like those by the other artists, had its own thing, but the title itself remains as unique as a mid-sized, black roller bag in an airport baggage claim.

Our next act, the lovely Jordin Sparks, started her set with the aching rocker “Battlefield." Sparks sings like a combination of classic Ann Wilson in “Barracuda" mixed with “Natural Woman"-era Aretha. I could hear her incredible voice before it hit the mic—cutting over my very loud amp and thunderous drums, bass, and thick key pads. That said, Sparks' “Battlefield" thematically follows Pat Benatar's '80s anthem, “Love is a Battlefield"—another case of great titles being recycled.

Look at the song that broke the adorable Katy Perry: “I Kissed a Girl"—a sexy vignette of hot girls making out (which I am not going to hold against anybody). Jill Sobule released her song “I Kissed a Girl" in 1995, complete with an MTV video and modest radio play. Sobule was working around Nashville about the same time that the teenage, Christian version of Perry was recording and working in Nashville, so it's probable that she heard it. Sobule is more than a little pissed about what she calls “song stealing," but the truth is, one cannot copyright a title—whether in a song, poem, book, or movie. You could legally write a book called The Holy Bible or Fight Club, though I doubt many publishers would want to touch it.

Look at William Shakespeare, clearly no hack when it comes to writing a story. By the time he got around to writing Romeo and Juliet, this story with this title had been written before. The plot is based on an Italian poem called The Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Juliet, published by Arthur Brooke in 1562. In 1582, it was rewritten in prose by William Painter. Bill S borrowed a good deal of his version from these two earlier versions. Ultimately, Shakespeare jump-started his imagination with the earlier work, but made it his own. It was the 1591 equivalent of the remaking of Ocean's 11 or True Grit.

I've had a few song-publishing deals and a handful of my songs recorded, but strangely enough, some of my back catalogs (one owned by Warner, another owned by Sony) will occasionally pay me on songs I'm pretty sure have not been recorded. These songs were entered into these catalogs, listed with BMI, but never pitched to any artist I'm aware of. Therefore, chances are that a few dollars of my measly checks may in part be from songs by the same titles registered to the same publishers and performing rights societies. When I brought this to Sony's attention they said, “Don't worry about it. It's small change and it may even be your song." This makes me think I should quickly write songs called “Yesterday" and “Sweet Home Alabama."

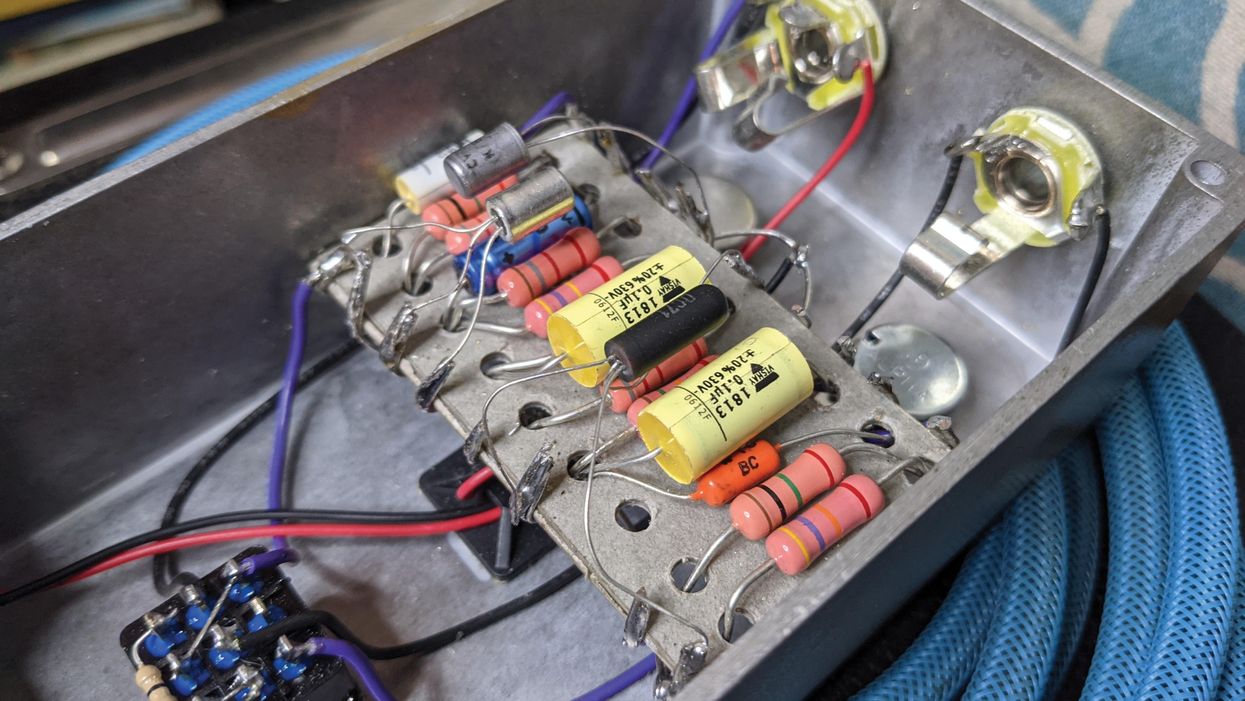

There's a great courtroom scene in the 2008 film Flash of Genius that illustrates what constitutes an original creation. The film tells the true story of a guy named Robert Kearns who takes on Ford Motor Co., who he claims stole his idea for the intermittent windshield wiper. In court, Ford argues that Kearns did not invent anything, but merely strung together a few capacitors. This is paraphrased a bit, but Kearns rebuts by addressing the judge and saying something like, “Can you copyright the word it or was or perhaps the?" The judge replies, “No, you can't." Then Kearns reads Dickens' A Tale of Two Cities, arguing effectively that it's not the ingredients—be they words or capacitors—but the order in which one puts them that constitutes an original creation.

Every songwriter is influenced by other songs. That's why we got into the whole creative exercise. Our minds will make connections to what we've heard and borrow at will—sometimes stealing without even knowing it. Outright plagiarism is usually obvious, but sometimes similar work can result from different people having the same idea. It makes sense that if thousands of folks sit around with a guitar every day trying to make up a song, some of these people will hit on the same theme and phrases.

Long ago I read a quote from Eddie Van Halen who said, “There are only 12 notes and how you string them together is your style." My first thought was, “Wait a minute, there are only 11 notes. The 12th note is an octave." Once I got over that, Ed's statement eloquently summed it all up. Whether you are writing notes for a melody or writing words for a song, it's how you arrange the raw materials that matters.

John Bohlinger is a Nashville multi-instrumentalist best know for his work in television, having lead the band for all six season of NBC's hit program Nashville Star, the 2011, 2010 and 2009 CMT Music Awards, as well as many specials for GAC, PBS, CMT, USA and HDTV.

John's music compositions and playing can be heard in several major label albums, motion pictures, over one hundred television spots and Muzak... (yes, Muzak does play some cool stuff.) Visit him at youtube.com/user/johnbohlinger

or facebook.com/johnbohlinger and check out his new band, The Tennessee Hot Damns.