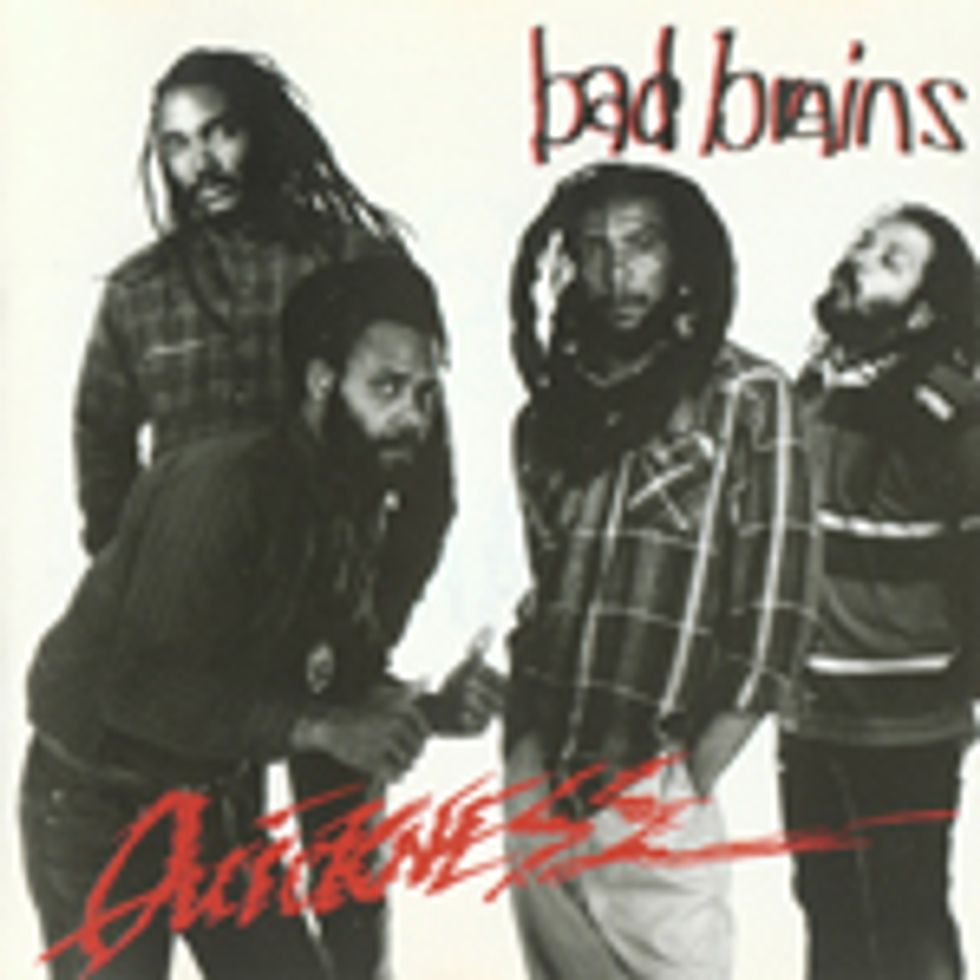

Photo by Frank Okenfels III

When it comes to bands who’ve altered the course of musical history with mind-blowing creativity and yet somehow never really gotten their due, Bad Brains is right up there with Spirit, the Velvet Underground, Moby Grape, and the Stooges. Despite these bands’ stylistic differences, each shares the distinction of dragging modern music kicking and screaming in a fresh new direction and heavily influencing countless bands that went on to greater fame and fortune.

To be fair, in the case of Bad Brains, the fault wasn’t entirely that of fate or a fickle music industry. The band’s lack of mainstream success has had at least as much to do with their two-edged eclecticism and the unpredictability and substance-abuse issues of lead singer Paul “H.R.” Hudson—a savant who, in his heyday, could seamlessly channel the most alluring elements of Curtis Mayfield, Bob Marley, Johnny Rotten, and a rabid old-school hip-hop emcee.

Formed in Washington, D.C., in 1977, the Brains began as a Return to Forever and Mahavishnu Orchestra-inspired jazz-fusion outfit called Mind Power. But then the four—H.R., drummer brother Earl Hudson, guitarist Gary “Dr. Know” Miller (aka “Doc”), and bassist Darryl Jenifer—got turned on to Black Sabbath, the Damned, Bob Marley, and the Ramones (a song by the latter inspired their name change). Just as importantly, they all joined the Rastafari spiritual movement, which would henceforth imbue their work with a message of peace, positivity, and perseverance.

Even so, within two years of their newfound fascination with raging volume, seemingly incongruous genres, and “the Great Spirit,” Bad Brains had been banned from most D.C. clubs because of their raucous stage performances. And though Jenifer, Doc, and Co. went into the studio soon after relocating to New York City in 1980, the reverb-drenched reggae-punk tunes from those dates inexplicably laid dormant until the 1997 release of The Omega Sessions EP. Consequently, Bad Brains’ first official album was 1982’s eponymous ROIR Records release—a debut chock-full of breakneck beats, raging power chords, raw-toned shredding, and bass lines so thrash-tastic they make your hands hurt just listening to them.

Bad Brains Must-Hear Moments

You can’t call a band legendary and then leave people hanging around with no proof.

Check out these tunes on Spotify, YouTube, iTunes, Rhapsody, or your MP3 store of choice.

“Stay Close to Me”

The Omega Sessions (1980)

Gary “Dr. Know” Miller’s tastefully restrained chukka-chukka reggae

rhythms float atop a warm wave of reverb, alternating with crunchy

power-chord stabs in the choruses, while Darryl Jenifer’s bass lines

bob and slither irresistibly, and H.R.’s vocals paint a picture of a

Rasta-inhabited Motown.

“Big Take Over”

Bad Brains (1982)

Doc layers Morse code-like pickup-pole tapping over a tapped lick

on the intro to this barnburner before Jenifer and drummer Earl

Hudson jump in with a relentlessly pulsating drive. At 2:14, Miller

augments his feedback-soaked solo with subtle wah.

“Right Brigade”

Rock for Light (1983)

Working with the Cars’ Ric Ocasek in the studio, Bad Brains redid

a few tunes from their previous album, including “Rock for Light.”

The whole album shifts a bit more toward metal, and at 1:30 on this

track Doc rips out a solo with a catchy pull-off lick punctuated by

bent notes that offer a breather before he shreds his way up the

fretboard.

“Return to Heaven”

I Against I (1986)

Doc starts things off with a reverse whammy-bar dive and an

angular progression before the song settles into a midtempo funk-metal

groove of the sort that actually does both genres justice.

H.R.’s vocals vacillate between ethereal and swirling jungle calls,

and at 1:50 Doc’s razor-toned solo begins and ends with hummable,

impeccably timed triplets and climaxes in the middle with a

rapid-fire staccato lick.

“No Conditions”

Quickness (1989)

H.R. rejoined the Brains after Jenifer and Doc cut the instrumental

tracks with Cro-Mags drummer Mackie Jayson and singer Taj

Singleton, but thankfully they swapped the latter’s tracks with lastminute

H.R. cuts. The result is a powerhouse riff fest with snarling

vocals, raging artificial harmonics, a lyrical, delay-drenched solo,

and a totally moshable groove.

“Let There Be Angels”

Build a Nation (2007)

Whereas so many artists mellow out and settle down as they age,

Doc, Jennifer, and Earl Hudson send that notion to the afterlife on

this number from the Adam Yauch-produced album—it positively

seethes with some of their fastest, tightest, and most ferociously

chugging grooves ever.

Their 1983 follow-up, Rock for Light, was produced by the Cars’ Ric Ocasek and featured a more metallic edge, but it wasn’t until 1986’s I Against I that the band got any real visibility. Produced by Ron Saint Germain (Sonic Youth, Living Colour, 311), it boasted a masterful blend of dynamics, a more organic-feeling interweaving of styles, and an overall looser, funkier vibe—all complemented by just the right amount of studio polish. It got airplay on MTV and had an undeniable influence on bands like Living Colour, Fishbone, and the Deftones.

But from that point onward, H.R.’s eclectic personality, itinerant tendencies, and desire to focus more on reggae/dub, world music, and jazz, pretty much threw a monkey wrench in Bad Brains’ plans every time things got going in their favor with major labels and high-profile advocates within the industry. He and drummer/brother Earl left and returned to the fold multiple times over the years, and each time Jenifer and Dr. Know would soldier on with various frontmen and drummers, none of whom could hold a candle to H.R. and Earl.

H.R. hasn’t changed a whole lot in the new millennium, either. The 56-year-old is as unpredictable as ever (at a 2006 CBGB's show, he showed up wearing a bulletproof vest, a motorcycle helmet, and a headset mic that made it difficult to hear anything he said), but when he’s guided by a steady hand in the studio—as he was by the late Beastie Boy Adam Yauch (aka MCA) for 2007’s Build a Nation—he’s stepped up to the plate and helped Doc (now 54), Jenifer (52), and brother Paul (55) hit it out of the park.

Last November, the legendary foursome released their 10th studio album, Into the Future. While the vitality and seething energy of H.R.’s youth is understandably in short supply—he’s now more inclined than ever toward reggae-flavored paeans to “PMA” (positive mental attitude)—he still turns in dynamic performances like only he could. Meanwhile, Doc, Jenifer, and Paul Hudson flex their juggernaut chops in all the ways die-hard Brains fans wanted them to—and then some.

We recently spoke with Jenifer and Doc about the sessions for the new album, their go-to gear, and their long, storied career as hardcore legends fighting to get their due.

Into the Future is stacked to the gills

with the sorts of inimitable Bad Brains

grooves that no other trio of musicians

on the planet can replicate—even when

the progressions are simple. What do you

attribute that to?

Darryl Jenifer: We started out in our teens

and early 20s, and it’s about building chemistry.

Our chemistry goes way back to, like,

1978. We’ve played together for so many

years that it doesn’t really matter about the

notes—it’s just the combination of our different

sensibilities about what we’re doing.

When we go to break it down to mosh

sections of chunk, the way Doc mutes his

guitar, the way I like to hear chords and

octaves—it’s all about our sensibilities. It

just comes from playing together—and

struggling together, more than anything.

I shouldn’t even say “playing together,”

because a lot of cats can play together but

they never really develop a chemistry. It’s

about struggling together, living together,

and trying to achieve your goals. I think any

combination of musicians can achieve that.

Gary “Doc” Miller: That’s what it’s about. We went to school together, we’ve known each other for 40 years or more, and we’re brothers—and H.R. and Earl are siblings. [Laughs.] It’s personal and spiritual—it’s all connected.

Does that “chemistry” extend beyond just

musical considerations?

Jenifer: I’m talking about lifestyle chemistry—growing up with each other, knowing

if a cat’s grumpy or likes to joke all the time

or if one guy’s serious. All these personality

traits come together when we sit down

to make music, because we’re brethren—brothers together. We get angry with each

other, we get joyful with each other, and

all of that comes through in the music.

When we say, “All right, Doc, we’re going

to go from G to G# and then we’re going

to break it down here and do this and then

take off really fast”—once we communicate

that to one another, then our chemistry of

knowing and loving each other and going

through shit with each other takes over and,

thus, you have the Bad Brains sound.

Doc, you were a pretty accomplished

fusion bassist before switching to guitar

in the mid to late ’70s, right?

Jenifer: He was a very proficient bass

player. Like, way better than I was—than

I am. Doc is sick on the bass. He was the

dude that everybody wanted to play like

when we were coming up as teenagers. He

was so good on the bass that I didn’t even

want to go around when he was there. He

could play all that Graham Central Station

stuff—like “Hair”—the way it really sounded

on the record.

Doc: Yeah, I used to play the bass back in the day, and Darryl used to play the guitar. We were in garage bands playing funk covers and whatnot.

Did starting out on bass make you

approach guitar differently when you

changed over?

Doc: Absolutely, absolutely. It made me a

foundation and made me a good rhythm

guitar player. It made me understand music

from the roots. A lot of times I write on the

bass or I think like a bassist—I think about

holding it down. Both of us are like that.

Darryl is like a rhythm guitarist and bass

player in one. Every time I play with other

bass players, I’m, like, “Where’s the oomph?”

That’s why we never took on another guitar

player, and that’s why I do my rhythms and

my leads the way I do—because Darryl just

holds it down.

Which players inspired you guys in the

early years?

Doc: I was really influenced by players like

Verdine White [Earth, Wind & Fire] and

Stanley Clarke. It was, like, “Damn—these

dudes are out there.” Verdine is crazy. I

used to dibble and dabble in the fusion of

the early ’70s, too. I’d wear those records

out trying to see what the hell was going

on there. [Laughs.] Return to Forever was

definitely influential on guitar and bass. It

was inspirational for me to start playing the

guitar when Al Di Meola got in [Return

to Forever], because he was so young and

such a badass. I was, like, “Yeah, uh-huh—I

could do this.” [Laughs.] I liked all the

Return to Forever guitarists—Bill Connors,

Johnny Mac [McLaughlin]. I liked Allan

Holdsworth. On bass, it was Larry Graham.

I had the beautiful opportunity to see all

these people over the course of a five-year

span. We saw Earth, Wind & Fire four or

five times, and P-Funk played every month

in their heyday in D.C. Yes, Zappa, Thin

Lizzy, Graham, and all the funk and soul

stuff—Tower of Power. You name it, we

saw it. It was all happening, every week.

Jenifer: As far as rock, it was Sabbath and “Iron Man” and shit like that—but I also grew up with a lot of stuff like John McLaughlin and Return to Forever. That was out when I was young—15 and 16. I listened to a lot of music-school cats when I was coming up, but also a lot of Motown.

You’ll be stoked to hear we’ve got an interview

with Larry Graham in this issue.

Jenifer: That’s my hero! Without him, I

wouldn’t be nobody on the bass. Without

Graham, there’s no DJ, to tell you the truth.

Between him and [James] Jamerson. . . .

Darryl, you started as a guitarist—how

did that come about?

Jenifer: I had a cousin that played the guitar,

and I was really young—about eight years

old—and he had a band, a funkster sort of

band, and I found it fascinating. All the amps

and the chrome and all the sparkling stuff—I

just got attracted to it at a very young age.

My cousin told me if I could learn to play

something then he would let me play in the

band. He wound up selling me his guitar,

and I taught myself how to play stuff like

“Get Ready” by the Temptations—just the

first part, like [hums opening riff]. And then

it grew into a competitive thing, like, going

into the alley—back then it wasn’t about rapping

and all. I’d be out there and I’d say, “I

can play Ohio Players” or whatever. And then

you’d run in the house and get your guitar

and come back out to the alley and show off

that you can play little parts.

How long after that did you start

playing bass?

Jenifer: When I was about 12, the guitar

went in the closet and I started playing with

model cars and riding my bike. Then when

I got to be about 13, I pulled it back out

and got into bands around my neighborhood.

I was in a little band called the Young

Explorers, and we were playing early-’70s

funk. I played rhythm guitar, but every

time the band would take a break, I would

ask the bass guy, “Can I play your bass?” I

used to pay him sometimes—“I’ll give you

three dollars if you let me play your bass for

a little while!” [Laughs.]

Darryl Jenifer with his go-to ’81 Modulus graphite bass at the Virgin Festival in Baltimore, Maryland, on August 5, 2007. Photo by Eddie Malluk

Do you think it affected your style to start

out on guitar and then switch to bass?

Jenifer: Because I was a rhythm guitarist

and I was tuned in to Sly and the Family

Stone—“Thank You (Falletinme Be Mice

Elf Agin)” and all that—I think it gave me

a certain insight. I really know the inner

workings of the motion between rhythm

and bass. Some people hear me say that

I’m not a musician. I give musicians credit

because they took the time to learn music

[theory] and all that, but I have the knack to

lay it down. To lay it down is different than

knowing music. There are a lot of cats that

know music, but they don’t know how to

lay it down. My whole career has been about

inventing my own style on the fretboard. I

look at the fretboard like Braille, in a way—it never meant notes, like, G and F and B

and C to me. I guess I had ADD or something,

because I never really cared about it in

that way. I only cared about it in the way of

creating these little passages and movements.

When you joined up with Doc and the

rest of the band, the roles were a little different

than now, right?

Jenifer: When we got together, Doc was on

guitar and H.R. was playing bass, and Earl

was playing drums. They had a fusion group

called Mind Power, but we all went to the

same high school and hung out in the same

places. Being brothers and dudes in the hood

and all playing music, we all knew each

other. H.R. wanted to be the singer, so he

said, “Let’s get Darryl to play bass.” Earl was

just developing his fusion sensibilities, Doc

was kind of getting into being an intellectual

kind of guitarist—wanting to bring some

sort of spirituality and thoughtfulness to his

playing. He didn’t want to be a shredder. We

wanted to be musicians, not just dudes playing

some shake-your-rump-type shit.

So when we were on this thinking-man’s jazz-fusion trip, I was still listening to rock music, but my buddy Sid McCray came over to my crib and had the Ramones and all that stuff, and I thought it was loud and cool. Having a fusion background and aspiring to be like Return to Forever, and then hearing the Ramones, I just said, “Yo, if cats think this is fast, watch this.” What punk rock brought was a certain freedom to riffs. Bad Brains took the freedom and the raucousness and the roughness of punk rock, but brought a little thoughtfulness to the musicianship.

There are very few musicians on the planet

who take inspiration from Return to

Forever and the Ramones and Sabbath.

Jenifer: Everybody has their blessing—I feel

blessed that I’m versatile. But it’s a struggle.

When I was a teenager, my cousin—who I

love—she used to say, “Darryl, why do you

listen to [fusion]? You’re crazy—you can’t

even dance to that!” There’s a lot of people

that are, like, “How do you get enjoyment

out of listening to [Return to Forever’s]

Romantic Warrior over and over and over and

over?” If they had Romantic Warrior on karaoke

[laughs] . . . I know every riff, measure,

beat . . . everything. I listened to that album

a billion times, and I played the bass till I

fell asleep. As a teenager, I was completely

into it—I didn’t go to school . . . My father

snatched the bass from me one time and

held it up like a hatchet and wanted to hit

me! Every time he saw me, that was all I was

doing. Imagine you’re living with your teenage

son in an apartment in D.C., and every

time you come home from working hard all

day, he’s sitting in there, the place smells like

weed, and he’s playing the bass! [Laughs.]

Doc: We always liked music—from Bob [Marley] to Sabbath to the Clash to the Damned to Return to Forever. We would see these bands, and we never got pigeonholed or stereotyped music. As long as it was good music, we were into it. In the early ’70s, there was a lot of good music, and we were just open—like a sponge. Who’s to say you can’t play whatever you like? That’s why we are who we are. With the metal [influences], it was about the power. With the punk, it was the speed—although a lot of the fusion had the speed, too. It was marrying the power, the musicianship, and the speed to give it that superdynamic-ness.

Jenifer: Washington, D.C., is a really sophisticated music place in general. There was a friend of mine who brought records like Rare Earth and Return to Forever to art class. You’ve got the radio station WPGC, and they’re playing, like, “Taking Care of Business,” then you’ve got go-go music going all the time on the basketball court and everywhere in your life, and then you’ve got your Motown and soul music and your church music—it’s just all a part of your life. So if you’re a musician dude, you’re going to say, “Damn—I like that!”

I used to listen to . . . we used to call it a “white-boy” radio station. I used to be able to play [Kansas’] “Carry on My Wayward Son.” [Sings main riff.] So, as a teenager from a black neighborhood, I would hear it on the radio and know that it was a cool guitar riff. I knew how to play “Iron Man,” I knew how to play the beginning to “Stairway to Heaven.” But also I knew how to play stuff off [famed fusion drummer] Billy Cobham’s Spectrum. I knew how to play [New York City funk band] Mandrill. I knew how to play a lot of the [Larry] Graham stuff.

Were you two and Earl pretty much on

the same page with all of that, or did you

guys introduce each other to new music

and then evolve together because you

were open-minded?

Jenifer: There were different levels between

us all. Earl was more into the jazz-fusion—he was listening to a lot of Earl Klugh and

George Duke—and when it got down

to me, that’s where the Sabbath and the

Zeppelin came from. As far as rock, H.R.

and Earl were more into the Beatles and

stuff like that—stuff I never really listened

to. Doc was more about Mandrill and early

Return to Forever, like, Where Have I Known

You Before—before Romantic Warrior.

So you basically wanted to marry the

musicianship and phrasing of fusion stuff

with the tones and power of metal and

the chaos and freedom of punk?

Doc: Yeah, you could say that. It was the

need for all of that, definitely. I’m sure there

are a lot of musicians who have the same

respect for different types of music, but

were—or are—afraid to pursue that because

of peer pressure.

They pigeonhole themselves because

they’re unsure of how marketable it will

be, you mean?

Doc: Definitely the marketability. I mean,

how do you market us? That’s our biggest

thing. It’s like, “Well, you’re not this and

you’re not that.” We’ve heard it a million

times, “We don’t know what to do with

you guys. It’s [expletive] great, but what

do we do here? What category . . . we can’t

put you on the radio.” [Laughs.] It’s like,

“Whatever . . . we do what we do. Thank

you, but no thank you.”

Why did your first recordings, The

Omega Sessions, not get released for 17

years? They’re incredible—every bit as

good as your first official release.

Jenifer: Y’know, sometimes stuff like that

is just a part of the life you’re living and it’s

not really looked at like a product or something

to be released. But I’d be the wrong

guy to ask that—Doc would probably

know more about that.

Doc: I don’t know what the heck happened, actually. We recorded it in a house. I was in the basement, Darryl was in one of the bedrooms, and H.R. was actually outside. We used a 4-track with big old knobs on the board—big ones. I think it was actually a Radio Shack [recording console] kit. I was, like, “What the hell is this?”

That’s amazing—that album has such a

live sound. It sounds like you’re all in the

same room.

Doc: No, we were all over—wires going

everywhere. That’s why you can hear me say,

“Can you hold this for a second?” [Laughs.]

Gary “Dr. Know” Miller onstage at the 2007 Virgin Festival in Balitmore, Maryland, with “Old Blackie,” an S-style axe with ESP body and neck, and custom DiMarzio pickups. Photo by Eddie Malluk

You guys got some early praise for 1980’s

“Pay to Cum.” Even by today’s standards—

where you can see a crazy-good

8-year-old playing on YouTube—that

bass line is incredibly fast and difficult.

What do you remember about writing

that, Darryl?

Jenifer: Well it wasn’t that fast at first. It

started very slow, but the times change.

We’d play “Pay to Cum” at a show in the

late ’70s and early ’80s, and the kids who

thought we were playing fast would start

their own bands and then they’d play faster

than us. Then we’d end up playing at gigs

where we’d come on after them—so then

we end up playing faster than them. But it

wasn’t conscious. That’s just what happened

when Earl got back there and counted off

with his sticks.

I Against I is often considered the first

fully realized example of all the classic Bad

Brains elements—it’s got hardcore, metal,

and reggae, but it’s also surprisingly funky.

Did Ron [St. Germain, producer] help

forge the Brains sound, or was he merely

witnessing part of your evolution?

Doc: The Spirit produces our records—us

and the Spirit. Ron was influential in capturing

the essence of the music. We went

to a lot of different studios—like, the best

studios in the world. Ron would dial that

shit in and say, “All right, hit it boys—bam!” Ron will shoot from the hip. He’s so

freakin’ talented.

Jenifer: He did some things, but mainly effects, like on “Return to Heaven”—he did the little delay shimmers and stuff that you hear in the chorus. But as far as “House of Suffering” and all the rock shit, no one knows what to do with that except to let us get a good sound and kick it.

As far as the bass lines, I was trying to bring in a little Graham [vibe]. Sometimes I play with a pick and my [plucking-hand] fingers and my thumb on one song. Like on “Secret 77,” I wanted to play the thumb on the verse, and then I dropped to the pick during the bridge, and then my fingers during the chorus. So I go from snapping it—not a real bona fide funky snap, but more of a hybrid funk snap—to regular, lay-it-down and complement-the-chorus- type finger work, like Jamerson.

Do you curl the pick up under one

finger or what?

Jenifer: It’s in the folds in the palm of

my hand, and then I can drop it down

when I need it.

Let’s talk about the new album.

“Popcorn” is prototypical Brains—it’s

got angular, syncopated power chords

ripe for the moshing, but it’s also evolutionary:

Doc, during the choruses

you’re playing these dense, complex

chords that are pretty uncommon to

hear in a setting with such thick distortion.

And Darryl, you’re playing some

of your most overtly funky bass lines

ever. How did that song come about?

Jenifer: That’s a song that’s driven

by H.R. He was in one of his good

moods—like, “It’s on like popcorn with

all the pretty ladies!” That’s a D.C.-like

rock-funk hybrid, a combination of

being from the hood and go-go—like

Chuck Brown meets the Bad Brains.

Doc and I put our minds to the chunk,

but we didn’t want the chunk to be the

same old chunk. Doc is always reaching—always going somewhere else—and

I’m always trying to make it so you

don’t notice that he’s trying to go somewhere

else! I’ll look at him and think,

“Why is he looking for another chord

or somewhere else to go?” I’m more of a

minimalist, and he’s keeping it going. He

knows what he wants to play—he doesn’t

want to play that same old shit.

Doc: I don’t know how we do it—we just do it. Making all the different flavors fit is just second nature to us. We don’t even think about it. It just happens.

But do that many different types of

sounds come together pretty fast, or did

that song get hammered out and evolve

over time?

Doc: Ninety-nine percent of the time, they

just come like that. It’s just, “All right, let’s

go to the B.” “No, let’s go to the C.” “Play

the Z# there. “Okay!” “Y’know that chord

there—that Fmaj7minb5 to the fifth power?

That! Here we go—bweeeeee!” [Laughs.] We

don’t really sit down and beat the damn

songs up—then all of the vibe is gone.

Speaking of musical technicalities, where

did you learn your chord and scale theory?

Doc: Books and just playing, y’know?

I had an old Mel Bay jazz book. And I

would buy Stevie Wonder tablature books

and theory books on [scale] modes and

whatnot. I picked out a few scales that I

liked, and it was like, “Let’s write a new

song. I just learned this scale—let’s start off

with this.”

“Make a Joyful Noise” has some of your

most overt fusion tones ever, with those

Wes Montgomery-type octave parts and

the really clean, modulated tone.

Doc: This record was unique in the respect

that we wrote it in the studio. So we had

to rehearse after we recorded the stuff in

order to learn the songs again—because we

would write and record a song and then

move on to the next one. We said, “Let’s

just go in and roll the dice.” I always try to

keep it fresh for myself so I don’t get bored.

[Laughs.] It’s creativity—you can’t be a

cover band of yourself.

On songs like “Fun,” where there’s this

really badass, syncopated chugging, do

you use a noise gate to make the cutoffs

between grunting chords tight and more

articulate, Doc?

Doc: I mostly mute it with my hands. Live,

I use a little gate, but it’s mostly muting

with the palm.

Let’s talk more about your gear over the years.

Doc: My first guitar was a Bradley Les Paul

copy, but Les Pauls were uncomfortable. I’d get

a belly rash and arm rash—because we were

digging in, y’know? In the CBGB’s DVD [Bad

Brains: Live at CBGB 1982], most of that was

an Ovation [UKII 1291] that Ric Ocasek gave

me during the [Rock for Light] record. It had

two humbuckers and was really light. [Ed. note:

The circa-1980 UKII 1291 had an aluminum

skeleton and a Urelite foam body that looked like

mahogany.] I also had a B.C. Rich Eagle that

got stolen. When they first came out I was a

happy young man—they had all these phasing

switches and different tones! [Laughs.]

I never really liked Strats because they were too tinny, but I got a black parts Strat[-style], which I still play live. That was when ESP first came out and they had the shop over on [New York City’s] 48th Street—they were originally a parts company. Old Blackie has an alder body, which I prefer because it has more oomph. The pickups are DiMarzios that Steve Blucher made for me. The [middle- and neck-position] single-coils are stacked humbuckers.

What about your newer guitars?

Doc: I have this 6-string from a [Swedish]

luthier named Johan Gustavvson that’s

basically a Les Paul Strat—it’s mahogany

with a maple top and Strat[-like] cutaways.

It’s a freakin’ badass guitar! It’s got Duncan

pickups and a blower switch that goes

straight to the humbucker, and three 3-way

coil-tap switches—which is kind of like the

B.C. Rich with all the switches. I’ve also

got a Gustavvson 7-string and a Fernandes

with a Sustainer in it. I use Floyd Roses on

all of them.

Doc, in the early years, you used Marshall

stacks or old Fender combos, but for the

last few years you’ve primarily been using

Mesa/Boogies, right?

Doc: Yeah. Oh man, I could shoot myself

for all the stuff I got rid off. I had a Marshall

that Harry Kolbe modified for me, and

sometimes I borrowed people’s amps, usually

Fender Twins. I’ve been using Boogies

for a minute now. We were on tour with

Living Colour, and Vernon [Reid]’s tech

was a rep at Mesa. Vernon was using the

Dual Rectifiers, but they didn’t have enough

headroom for me. So I A/B/C’d the Marshall

with the Dual and Triple Rectifiers, and the

Triples had good headroom and could hold

the bottom but also clean up like a Twin—because I need to have a very versatile amp. I

use the 6L6 version, because it’s cleaner.

Darryl, are you still using Ampeg heads

and cabs? And did you use your trusty

old ’81 Modulus for Into the Future?

Jenifer: Yeah. I’ve got an old SVT Classic

Anniversary Edition. Live, I use two of

those and two 8x10 cabs. I use one bass—the green Modulus graphite bass. I’ve used

that for all my rock stuff since 1982. When

I first bought it, it wasn’t because of anything

I heard about them. It was because I

knew that it was a material that wouldn’t

have to be babied. Every time I picked

it up, it would feel the same and I could

throw it around and it would fall on the

floor and it would be okay. The bass has a

sound that just stays no matter what.

Dr. Know’s Gear

Guitars

Johan Gustavvson 6- and 7-string guitars

with Seymour Duncan pickups, ESP Sstyle

with custom DiMarzios

Amps

6L6-powered Mesa/Boogie Triple Rectifier

heads driving Boogie 4x12 cabs

Effects

Line 6 POD HD PRO 500, vintage Uni-Vibe

Strings and Picks

Dunlop Nylon .60 mm picks, DR .009 and

.010 sets with a heavy bottom

Darryl Jenifer’s Gear

Basses

Green 1981 Modulus graphite J-style,

white Modulus J-style (backup)

Amps

Two Ampeg SVT Classic Anniversary

Edition heads driving two Ampeg 8x10 cabs

Strings and Picks

Dunlop .60 mm picks (“But I play with the

butt end”), Rotosound .045 sets

After all the changes over the years, how

do you feel about the new album?

Doc: The records are what they are, though,

y’know? People take months and years to

do records. We go in, record the shit in two,

three days, and then mix a song a day and

that’s it—say, “Goodnight.” [Laughs.]

Jenifer: At this point in our careers, we just have to let the Great Spirit guide us through. We can attribute it to our talents and our perseverance, but at the end of the day it’s the Cosmic Force. To us, we’re a vehicle of the Great Spirit to spread a message of unity—the corny stuff, like hippies say: “Peace and love.” But I’m realizing after 30 years that mainly the message is that you can break the mold of what you’re “supposed” to be. Like, how the Beastie Boys could be the rappers, and we could be the punkers, and the Chili Peppers can be the funkers. There was a time in music when everybody couldn’t do that. But the Great Spirit, not by any choice of ours, made us cats that had to come out there, all black, and shredding. We were dead serious. I can only say, 30 years down the line, that if I was in the crowd when we first came out in D.C., I would’ve said, “Damn!” Because not only did we have our PMA behind us, but we were very competitive about making sure our fusion riffs were jumping off. That’s why I always described our music as progressive punk—we’re thinking about the music. Real punk-rock dudes don’t think about the music—they don’t give a shit.

YouTube It

Need proof of why Bad Brains is considered one of the most influential punk bands of all time?

Check out these clips on YouTube to see the band in its awe-inspiring prime.

In this hour-long 1982 clip of

Bad Brains at the legendary

CBGB’s in New York,

you get an amazing look at

the band’s palpable energy.

Backed by a makeshift wall

of Marshalls, Gary “Dr. Know”

Miller taps out the show

opener, “Big Takeover,” and

then singer Paul “H.R.” Hudson,

bassist Darryl Jenifer

(who, sadly, is off camera

for most of the show), and

drummer Earl Hudson join in

to tear the place apart.

After 12 minutes of footage

showing H.R. prowling the

same CBGB stage as the

human embodiment of hyper-kinetic

energy, the primal frontman

settles down, Miller kicks

on some cavernous reverb,

and the band lays back into

deep reggae grooves as NYC

punks of all shapes and colors

dance alongside them onstage.

If you only watch one portion

of this excellent 25-minute

clip from a 1987 spring-break

gig in Florida, start at the 3:30

mark and witness Miller—equipped with a Charvel

“super strat”—lead the band’s

raging intro to the then-brand-new

song “House of Suffering.”

Immediately after, there’s

an über-funky rendition of

the Beatles’ “Daytripper”

that finds Jenifer getting the

crowd moving with his go-to

Modulus J-style bass.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)