What hasn’t been written about bassist Bootsy Collins?

In 1970, when Collins was just 18, he joined James Brown’s band and played bass on timeless classics like “Sex Machine,” “Super Bad,” and “Soul Power”—which for some people is enough to establish him as one of the instrument’s all-time greats. But Collins was just getting started, and two years later he joined Parliament Funkadelic.

Brown taught Collins how to interpret groove—he emphasized the one, which means resolving phrases on the downbeat—and Collins taught that concept to his new band. That one defined the sound of P-Funk, which in turn helped define the sound of funk, which—thanks to sampling and the popularity of hip-hop—was influential in shaping the next 40 years of popular music.

Collins is central to seminal Parliament releases like Chocolate City and Mothership Connection, and even his “solo” project, Bootsy’s Rubber Band, scored a number one R&B hit with “Bootzilla” in 1978. He’s also a frequent collaborator and since the ’80s has worked with everyone from Bill Laswell to Fatboy Slim to Herbie Hancock to Buckethead. In 1990, he was at the top of the charts as part of Deee-Lite’s mega-hit, “Groove Is in the Heart,” and in the early 2000s performed the Monday Night Football theme with Hank Williams Jr.

And that’s just part of his curriculum vitae.

Collins’ tonal wanderlust—in addition to his innovative playing—defined the sound of funk as well. Eddie Van Halen has the Phase 90. Jimi Hendrix had the Uni-Vibe. And Bootsy Collins has the Mu-Tron III envelope filter. That watery thump isn’t just a Collins’ trademark—that’s what funky music sounds like.

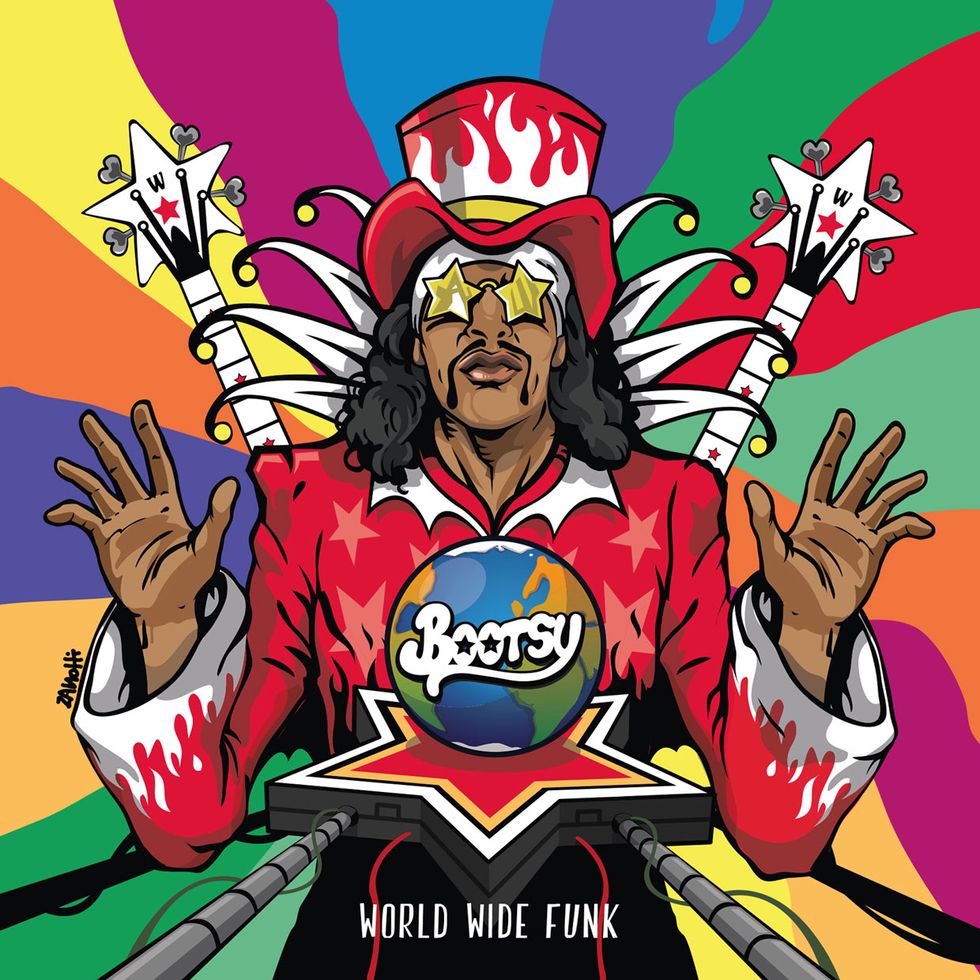

Collins was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame two decades ago, but he not only shows no signs of slowing down, he shows no signs of becoming a has-been. His new album, World Wide Funk, is surprisingly fresh. “I was trying to intertwine some of the young energy,” he says. “That’s kind of what I hang around now, a lot of young musicians, and being around that inspires me even more. I tried to incorporate that into the album.”

World Wide Funk features guest appearances from fellow bassists Victor Wooten, Stanley Clarke, Manou Gallo, and Alissia Benveniste; guitarists Eric Gales and Buckethead; drummer Dennis Chambers; rappers Doug E. Fresh, Chuck D, Dru Down, and the Blvck Seeds; singers Kali Uchis, Musiq Soulchild, and October London … and many others.

But this is Premier Guitar, so when we got Collins on the phone, our first order of business was gear. We got the lowdown on his early instruments and the history behind what eventually led to his iconic star-shaped basses. We also discussed his never-ending obsession with pedals, collaborating with other bassists, the recording of World Wide Funk, and—this may even be a first—we even got him to talk about his little known, yet very impressive, guitar playing.

You’re known for your distinctive star-shaped basses, but obviously, that’s not what you started with. I read that your first instrument was a guitar strung up with bass strings. Is that true?

Well, it didn’t have bass strings at first. It was a regular $29 job, a Silvertone guitar. The reason I put bass strings on it was because I wanted to play with my brother [Phelps “Catfish” Collins]. He played guitar and he was developing a good reputation. He’s about eight years older than I am. He was a teenager and I was, like, 9 years old. And from the beginning I wanted to play with him. So, I figured if I got a guitar, I could at least learn how to play and then the next step would be to play with him. When that next step came up, he didn’t need another guitar player, he needed a bass player. I didn’t have a bass, so I was like, “Okay, well, what do I do now?” I asked him if he would get me four bass strings. He got me four bass strings, I unwound the thickness of it at the end, I put them on the guitar, and voilà!—that was my bass guitar.

World Wide Funk, the latest album by Bootsy Collins, was mostly recorded in his Bootzilla Rehab home studio. It includes an intro by Iggy Pop and appearances by Victor Wooten, Stanley Clarke, Eric Gales, Buckethead, and Chuck D, just to name a few.

Did you still have that when you joined James Brown?

Yeah. He loved my playing but he was really done with that guitar. The color of it was beat and at that time Fender was the main thing on the market. Everybody had to play a Fender—either a P bass or a Jazz bass. I wanted one for the longest time, but I couldn’t afford it. He dogged me out about my little bass, man, like, “You can’t come up here on my stage anymore with that thing.” He wound up getting me a Fender Jazz bass.

Did you prefer the Jazz bass as opposed to the Precision?

Yes, especially at that time because I just loved the way the neck felt. It wasn’t wide all the way up the neck. It was just a perfect fit. And the sound of it—I loved the P-bass sound, too, but I liked the body shape of the Jazz. It fit real good.

Did you have a Vox bass with James Brown as well?

Yeah, I’ve still got that Vox bass [an Apollo IV] and I played it on one of the songs on the new album—I can’t think which one it was off the top of my head—but I played it on one of the songs and man, I mean, nothing sounds like that. It’s like a dead-string sound—those old flatwound strings on top of that hollow Vox bass guitar. It’s got a built-in fuzz on it and a built-in tuner. It was incredible. I used a lot of different things on this record to try to give me a facelift. I’m still keeping the old stuff, but I’m adding a little newness here and there. On different songs, I use different pedals as well.

Were you still playing the Jazz bass when you joined Funkadelic?

No, I went back to the P bass. That’s what everybody was into, back at that time. I was like, “I got to get myself together to play the P bass,” because the neck is different. I started playing it—and I started loving it. The first recordings I did with Parliament Funkadelic were with that P bass. And that P bass is in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame now [laughs].

Bootsy Collins’ first Space Bass was made in 1975 by a guy named Larry Pless at Gus Zoppi Music in Warren, Michigan, which was an accordion shop. Bootsy’s current signature Warwick star basses have five pickups with four outputs, each wired to different amps and cabinets. Photo by Ebet Roberts

When did you get your first star-shaped “Space Bass?”

The first Space Bass was made in 1975 by a guy named Larry Pless, at a place called Gus Zoppi Music in Sterling Heights, Michigan. I took a drawing in there and he was a young and up-and-coming guitar maker. Wouldn’t nobody make it. I was up on 48th Street in New York—all up and down there—and I was telling them about this star bass that I wanted, and nobody was interested. I had to find somebody that would do it because, first of all, I didn’t have no money [laughs], and second of all, nobody was interested because it wasn’t hot on the market. Nobody had a star bass. Nobody was talking about a star bass. I was like, “I’ve got to find somebody that’s just into doing stuff.” And Gus Zoppi Music store was an accordion store—it wasn’t even a guitar store where I found this guy. I just happened to go in there, I started talking to the owner, I asked him if he had any suggestions, and he said, “Yes. I’ve got a young guy that’s working for me in the back that might be interested because he’s always been wanting to make guitars.” So that’s how I found this guy.

Is the neck modeled after the Fender P?

After the Fender, yeah.

What about the pickup configuration? It has both the Jazz bass pickups plus other things. How did you design that?

That was designed originally off the Fender Jazz. Then I added the P-bass pickups—that and a couple of other pickups as well. It had a combination of the Fender P bass and then what I threw up in there that I liked myself. But it’s been a lot of upgrading since then.

What about the multiple outputs?

That multiple output allowed me to not use so many cables. It was just one cable that went to the pedalboard and that’s where the signal got split up. When I first did it, it was just 2-way out. Then it became 3-way and until, I would say, up until the ’90s, it became 4-way out. That’s what it is now. Every pickup has an output. There is one pickup unit in there that has two on one output, which is designed like the Fender Jazz bass. So, the guitar actually has five pickups.

Those outputs go to different amps?

Yes. They go to different amps and different cabinets onstage. It’s a whole wall of different tones, different sounds. The pedals go to different amps as well. It kept growing. It started with a small, maybe 3-foot pedalboard case, and then it grew up to around 6 1/2 feet. That’s where it’s currently at.

What’s on there?

I got everything and its mother [laughs]. You got maybe four to six pedals on what I call the high end and the same thing on the midrange. They’re different pedals, but they’re the same amount of pedals. You got three rows: you got ultra-high, you got high end, you got mids, and then you got the low end that goes direct, which goes to my sub-woofers. It’s a lot of configurations. People said, “Can’t you just plug the thing in and play?” But I was hardheaded and I wanted to always be “in search of” and “let me find these different sounds,” you know? I’m glad I did. It was very confusing to the engineers that started recording me first, because nobody was used to that. All they were used to was, “Plug that thing in and let’s hit it.” And, I don’t know, that era was changing. Synthesizers were coming in—it wasn’t in yet—but it was coming in. I guess I wanted something different. I didn’t want just the same old bass sounds that everybody got. So, I took a dive for it.

In the studio, do you use that whole pedalboard or do you just isolate what you need?

When I do outside studio work, that pedalboard goes with me. Whatever is in the pedalboard pretty much stays. When I’m recording myself in my own studio, I got the pedalboard plus a gazillion pedals if I want to throw something in or take something out. It’s easy for me at my studio where I can record things the way I want to. But when I go out doing stuff in other places, I just take the main pedalboard and those are usually the sounds I usually use. But on this new album, I was reaching for different things on different songs. I had access to any and everything, which was great. It helps fuel me as well. Uplifts me. Give me different sounds—when I hear different sounds, it motivates me. Either they’re good—they do something good to you—or it’s, “I don’t like that sound, let me try this other one.” Those are the kind of things I like to deal with. It’s kind of like painting. It’s like, “I don’t like that color. Let me try another color.” That is part of my creative process and it’s been that way forever.

Do different pedals and sounds inspire different types of riffs or make you play differently?

Yes, and that goes mainly for bass. But I found out even with Bernie Worrell—who was the keyboard player—I noticed any time he would do a different sound, it would make him play different. So, I didn’t feel so bad when I saw him doing it because he was really legit [laughs]. [Editor’s note: Worrell studied at the New England Conservatory of Music in the 1960s and was awarded an honorary doctorate just before his death in 2016]. Here I was from the James Brown school and we didn’t know nothing. I didn’t know how to read. All I knew how to do was hear these sounds and I wanted to play them.

Nowadays, do you experiment with computer modeling, plug-ins, and things like that?

I don’t. But I don’t knock it. It just seems like everything is kind of “pre-” now. I like the fact of having to find my way through different things. You can compare it like this: You know how they used to tell you to get lost? Well nowadays, you can’t even get lost because you’ve got the GPS. But getting lost was part of the experience. That was the part where you had to figure out how to get back—or how to get there. That’s being taken away and, to me, that was the fun part. I don’t want to take that away. All those old pedals, the old stuff, I love it—anything you can step on.

Check out one of Bootsy’s Rubber Band’s earliest concerts from 1976.

This is the mother lode for Bootsy fans. Collins takes a film crew on a tour of his home studio and shows off his huge collection of classic instruments.

Collins is known for his colorful costumes, but it doesn’t stop there. His bass tonal colors helped define the funk genre. “It’s kind of like painting,” he says. “It’s like, ‘I don’t like that color. Let me try another color.’” He’s shown here in 1990 with

his 1969 Ampeg upright bass. Photo by Ebet Roberts

How much does that original Space Bass weigh? It looks like it weighs a ton.

Well, you know, the first one actually did weigh a ton. I don’t know exactly what it weighed, but it was all solid wood and it was heavy. I never really paid it that much attention because I guess I was so young and energetic and I didn’t care. I just wanted to play that star bass. I didn’t care what it weighed. I was really concerned with how it sounded and what it looked like—and that’s pretty much it. If I could play it, then that’s what I wanted. The one I got now that’s made by Warwick, it’s much lighter. I notice it now because I put the old one on—the 1975 one—and it’s heavy. But I never noticed that before.

People don’t know that you’re also a guitar player. I interviewed George Clinton and Blackbyrd McKnight a few years ago [“Parliament Funkadelic: A Funk Guitar Roundtable,” March 2016] and they said your guitar playing is “dangerous.”

[Laughs]. That’s pretty deep. Nah. I just play what I hear in my head and that’s usually when we’re coming up with stuff—like a track and a riff. I’m pretty good at that because those are things I just hear. That’s probably why they said it. But being amazing and dangerous and all that? No, I doubt that very seriously.

Do you play the rhythm guitar parts on the new album? Is that mostly you?

A lot of it, yeah. And then Keith Cheatham, who was playing a lot on the road with us. He took Catfish’s place. I’d never found nobody that had Catfish locked down, other than Keith. He used to play with Sun [’70s/’80s R&B group], and he plays on a lot of this new album. It’s hard—it’s almost becoming a dinosaur thing to be able to do that, because that’s not the emphasis now—but for me, it’s always about that groove, that lock, that riff, that hook. You get that going and then you space out. But of course, that’s the idea from back in the day. Now it’s like everything is outer space. But I can dig it.

Are your guitars recorded direct to the board or do you have guitar amps and effects set up in your studio as well?

I got amps and I got direct. I got the old 50-watt Ampeg with the two 12s. I mean, you name it. The old Epiphone, the old Gibson, the old Fender Twin Reverb—all that old stuff, I got it. I got the B-3 organ. I mean, fully blown. Musicians come in and have a field day. It’s like having a studio with things you can touch. These are things you can actually get on and play. And I don’t care what era a musician was brought up in, when he’s able to sit down, jam, mess around, and experiment—when he can do that—that’s when he fully gets a chance to open up with his own self-expression and beat it out of himself. I think it’s very important to be able to beat it out, because otherwise you sit there and play with yourself. And I just don’t like playing with myself like that [laughs].

Do you play guitar with a pick or do you strum with your fingers?

With a pick. Just like my older brother Catfish. I learned from him and he was the greatest at it.

You feature a lot of other bass players on the new album as well. How do you arrange that?

It was about coordinating it and putting it together in a way that doesn’t step on anybody’s toes. This was like a team kind of thing. I didn’t want to do it where it all just sounds like a whooof. You know how you can put a lot of comedians together who are all great on their own, but when you put them together it just ain’t happening? Well, that’s the same idea. I wanted it to be where you had your own space and wasn’t nobody stepping on that. That’s you. It’s your turn.

You travel with a second bass player in your live act as well.

Yes. I started doing that because it kept getting more difficult for me to perform and take care of all the crazy business. It was just nuts. I’ve always loved to play, but to play and take care of all the airports—I mean, the road is just so stupid now—and it’s like I needed somebody I could rely on. I play and sing the songs and that was getting difficult—playing, singing, and trying to entertain the people was a little bit much for me. If it was just getting up there and playing, okay, I can do that. It was a lot of pressure lifted off when I added that. It made playing and being onstage a lot more fun.

When you play bass, does he lay out or do you just have two basses going?

He drops his volume or he leaves the stage, it just depends on what song it is.

How was the album recorded?

I engineered all the analog stuff. We did about 65 to 70 percent of the album here in the Bootzilla Rehab [home studio]—and the other parts we had to send out. Iggy Pop did the intro at a studio in New York. Dennis Chambers was on the road, so this time he had to record the drums where he was at. A lot of the musicians that I used were on the road—because it was the summer time and everybody was out. I took off to do this record. I had time to do whatever I needed to do. But the people that I wanted to get, I had to see if it fit into their schedule. Some of them came in and then had to leave right out. Some I had to send the files to, and me and my engineer, Tobe Donohue, interacted with the other musicians through Pro Tools.

When you record in the studio, do you sit in the control room or do you sit with your amps and play?

I’m in the control room, because once I pretty much got my sound, it always stays set up. That’s a good thing because when I used to have to tear it down to go out on the road, it was really draining to have to set it all back up. Through this album, it was always set up. All I had to do was turn it on and if I needed to put a different pedal or different thing, it’s all sitting right there in the control room.

You didn’t slap at first. When did you start doing that?

Well, when I first started, I was playing with my thumb. Then the new thing was the fingerstyle. When I saw Marshall Jones, of the Ohio Players, doing it with the fingerstyle, I was like, “Wow, that’s the new way of playing.” I jumped on practicing like that and I got good at it. And the next thing, Larry Graham came on the scene playing the slap, and I wanted to pick that up and infiltrate that with what I was doing. And that’s where it all started.

Many years ago, I was backstage at a P-Funk show and you showed up wearing an amazing jacket that had an American flag on one side and a Soviet flag on the other. Do you still have it?

Actually, I’ve still got that jacket. I mean, I probably wouldn’t wear it right now. [Laughs.]

Bootsy Collins' Gear

Assorted Warwick Signature models (star-shaped and double-horned) that are equipped with DR Strings BZ-50 Bootzilla Signature Bass Strings (.050–.110)

Amps:

Warwick PR 40 Jonas Hellborg Preamp (3), Hughes & Kettner BassBase 600, SWR Mo’Bass, Mesa/Boogie M9 Carbine, dbx 120XP Subharmonic Synthesizer, Monster Power PRO 2500 Rack PowerCenter, Mesa/Boogie Subway D-800 with matching cabs, Ampeg Portaflex with matching cab, and assorted custom cabs with stars.

it motivates me.”

Bootsy’s Pedalboard

Electro-Harmonix H.O.G.2

Electro-Harmonix H.O.G.2 foot controller

DigiTech Bass Whammy (blue)

Eventide H9

Mesa/Boogie Flux Drive

Boss BF02 Flanger

Boss DD-7 Digital Delay

Boss DD-5 Digital Delay

Beigel Sound Lab Mu-FX Tru-Tron 3X

Darkglass Duality fuzz

Electro-Harmonix Metal Muff

Electro-Harmonix Bass Micro Synth

DOD FX25 Envelope Filter

Panda Audio Future Impact I. Bass Synth

DOD FX59 Thrash Master fuzz

Pigtronix Mothership 2 analog synthesizer

DigiTech Whammy

DigiTech Space Station XP300

Lovetone Ring Stinger

Mu-Tron III

Korg ToneWorks G5 bass synth

Amptweaker FatMetal Pro

Xotic Robotalk 2

Radial Firefly DI

Pedalboard Overflow: Electro-Harmonix Big Muff Pi, Stone Deaf FX Fig Fumb V1 fuzz, Darkglass MicroTubes 900, Chunk Systems Octavius Squeezer analog bass synth, DigiTech Bass Synth Wah, and Eventide PitchFactor.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)