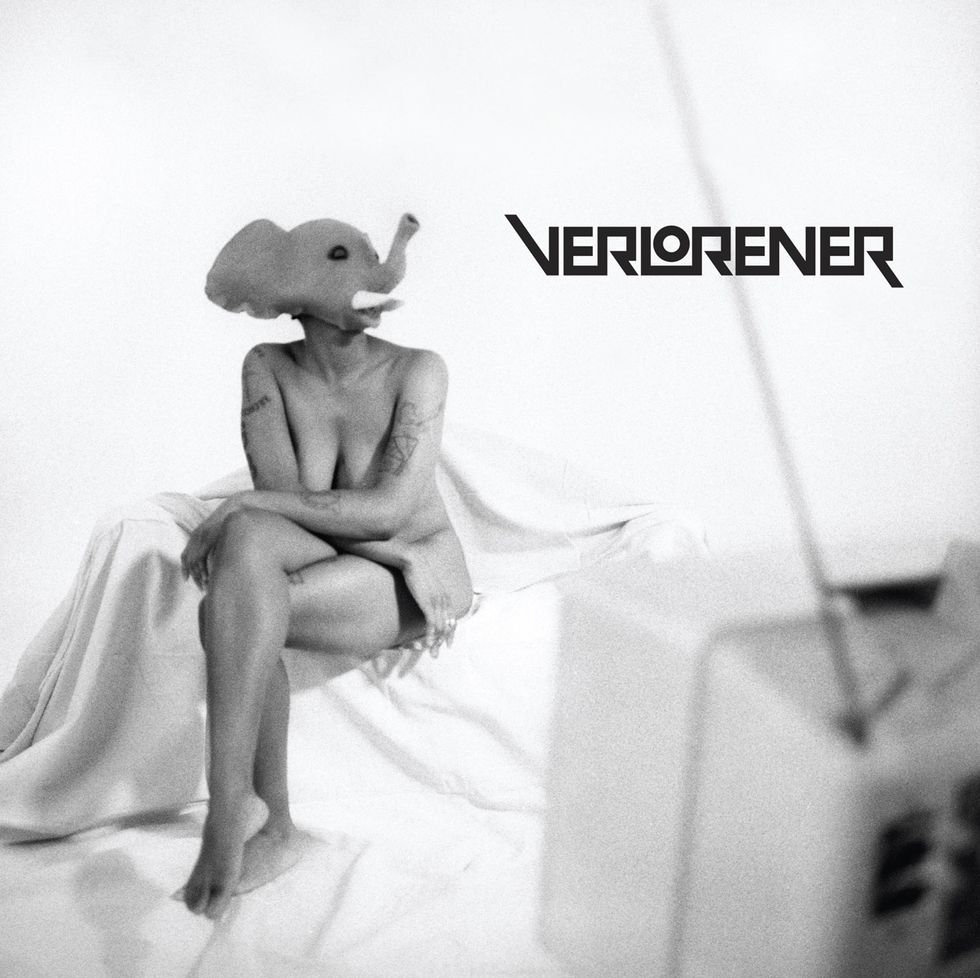

“Devil in the Room” Song Premiere

True to the sprawling experimental vision behind Emil Werstler’s Verlorener album, the video for its first single, “Devil in the Room,” was pieced together from found footage from many decades ago, interspersed with shots of Werstler on guitar.

“I went down to Atlanta and did a 14-hour shoot on a Sunday, and they had what they needed. It’s cool to see something that ancient—that digitized found footage—with glitching and all this weird stuff happening. The footage is a mixture of 35 mm, 16 mm, and 8 mm test film, with models and actors, combined with recently found 8 mm reels the director’s grandfather shot in the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s. They embody the Americana era that no longer exists and wasn’t as quaint as it seemed underneath the surface. Although this era is often the collective, romantic fantasy, we can neither recreate it, nor do we truly crave that way of living 50 years later. We all have the capability to be the devil in the room in our personal relationships as they fall to pieces.”

As for the music, the song takes its own distinctive path, departing from not just metal conventions but all genre restrictions. It’s just guitar, cellos, beats, and the sound of a person breathing. “That was Alastair Sims,” says Werstler. “He came in to do whatever he could to help me finish the record.” That included engineering the guitar tracks, assisting with production, and adding beats and programming. “Alastair was like, ‘I’ve got an idea, let’s roll with it,’ and I was like ‘I see what you’re doing and this is perfect because that just opens up more narrative for the music video.’ I can’t listen to music if it doesn’t go somewhere—it has to have a narrative.

“I also had a train recorded on my phone, and I knew it was going to pivot between the train noise and the recording of a door opening, which was the door in the house I lived in at the time. There was a lot of field recording on that song, now that I think about it.”

Emil Werstler prides himself in bringing modern semi-hollowbody guitars to the world of metal. Here, he poses with his Paul Reed Smith JA 15 with low-turn pickups. Werstler also uses five other PRS guitars, including a baritone model.

Photo by Alex Morgan

Emil Werstler: Like Django Reinhardt Meets Depeche Mode

Emil Werstler has seemingly never lacked focus. It ripples through the intensity, dynamics, and control evident in the music on his debut solo album, the recently released Verlorener. It’s also a quality that’s propelled his career. Werstler started teaching himself guitar at age 12, spent his college years at the Atlanta Institute of Music, and by 21 he’d graduated to the co-lead-guitar gig in Dååth, and later joined Chimaira, making a name for himself in the metal and guitar communities as a virtuoso, and a strikingly singular one at that. But, and with a lot of emphasis on that preposition, Werstler has never really been a “metal” guy.

“When I was in metal bands, people couldn’t understand … I was totally blind to what’s coming out, what band’s doing what, who’s in, who’s out. I don’t listen to that stuff at all,” he says. Which is largely why Verlorener—which is his solo moniker as well as the album’s title—doesn’t resemble the past 14 years of his output, in any way.

“On this project, I was making my departure from playing metal,” says Werstler, who also produced the album and regularly contributes lessons to Premier Guitar. “Everybody involved knew that my back was against the wall and something awesome had to come out of me.”

Verlorener is a name derived from the German word “verloren,” which roughly translates to forlorn and hopeless. It is Werstler’s antidote to his disenchantment with working the same musically restricted path for the past decade-plus. A combination of high-energy jazz guitar, industrial beats, and minimal orchestral instrumentation, the album is dystopian, compositionally straightforward yet conceptually provocative, and alien to the ears—in the best way possible. So our conversation began:

I was really blown away by Verlorener—your sound is so singular.

I most definitely take that as a compliment because the whole thing was kind of risky. I’ve always sounded like myself and put a lot of effort into that, but I basically dropped off the face of the planet from playing in heavy metal bands and touring nonstop to do this. And it’s kind of new, music-wise, so a lot of people don’t really know what to do with it. Even booking agents and promoters and PR people. That’s exciting, but it also comes with its drawbacks, because, for example, if you look on iTunes, it’s categorized as “alternative” because there’s no other label for it. There’s no “experimental” genre or something like that.

What motivated you to make your first solo album?

It’s taken about four, five years. It was done at different studios, kind of spaced out over long times. The first song took forever to finish. The whole reason of doing this was to keep me interested, because I was losing interest fast—going out and touring and playing the same songs every night the exact same way. You can’t experiment too much because you’ll piss off your heavy metal fans. This is definitely a way for me to save myself, keep paying attention, enjoy playing music, and try to really push the boundaries of it.

How did you develop those electronic, industrial-sounding beats?

On the second track, “Gothic Architecture,” that’s Deantoni Parks. He’s this drummer that originally started the Mars Volta. He plays a keyboard with his right hand, which has got ’80s Casio-sounding drums, sampled drums, sampled noises. And then on his left hand, he’s got the snare, the hat, and the kick—and that’s it.

To avoid making a “guitar record” for his solo debut, Werstler blended beats and samples with various genres, so country licks reside comfortably alongside jazz-based chord solos.

Does Parks appear elsewhere on the album?

There’s a ton of different people. It’s more like a Steely Dan kind of thing. Mainly because I wanted to work with everybody I wanted to work with, but I didn’t know exactly how the material was going to come out enough to depend on one musician.

What was the process like?

The bassist, Kevin Scott, would act as my musical director, and I would pick out the type of drummer I wanted for the song and have him reach out. Then, I would go down to Atlanta, where a lot of the stuff was recorded, jump in the studio, and track it. Then I would take it back to Canada, where I was living at the time, and hack away on the drums and do things like distort them, destroy them, go “I don’t know if I’m convinced on this chorus … what am I going to do?” and then I’d wind up putting in a programmed drum beat. A lot of experimentation like that.

In full metal mode, Werstler blasts out lead guitar with Chimaira. “I was totally blind to what’s coming out, what band’s doing what, who’s in, who’s out. I don’t listen to that stuff at all,” he says, regarding the world of metal guitar.

Photo by Brian Brown

Why did you choose to produce it yourself?

I wanted to assume as much control as possible, in more of a protective way: the same way that an actor or an actress would say, “Don’t put that footage out, I don’t look my best.” They’re protecting their brand. I just don’t really think that anybody knew what I was trying to say except me, so I had to go say it at whatever cost. And that cost was time, to get it right.

Given that you’re so clear on what you wanted to do, it’s surprising the album didn’t happen earlier.

It’s interesting to hear you say that, because everybody’s always expected a guitar record out of me, and I’ve never been a guitar record kind of guy. We’ve seen that enough. But the aesthetic of the metal stuff that I’ve done … I’m proud of what I’ve done, but I didn’t want that aesthetic in my work. I don’t want photos for this particular record. I feel like there needs to be a bit of mystique these days. Everything I did was very intentionally against the grain. Nothing on the record is really corrected. There’s intentionally out-of-tune guitars on there. There’s distorted drums. Every song on the record is one tempo all the way through. There’s no tempo mapping. The drums are not aligned, either. That would insult the drummers that came in and did a great job. I adjusted to their feel. The same with the guitar stuff: The record is actually a bunch of mid-tempo ballads and it’s intended to be that way.

What’s your background in guitar?

My original instrument was the piano. I was really young, too, so I didn’t have a barometer of, “Is this cool?” I took lessons for a long time as a kid, and then when the guitar came around, all my friends were doing it, and it became easier to learn because it became a friendly competition.

So, I started playing guitar and was self-taught until I went to school for music. I was so heavily invested that I knew what I was there for, to the point of when it was classical class, I would skip it, because I didn’t want to learn that style. I was really good at a young age, too, so by the time I got to school, I wasn’t really there to learn rock. I could play everything that was playable when it came to rock as a 17-, 18-year-old. But what I couldn’t do was control my harmony, my melody. I went there particularly to learn jazz, like straight-ahead bebop. When I graduated, I just did whatever it took—my goal was to make a living with the guitar in my hands.

Who do you think influences your guitar playing directly, in a technical sense?

If you put all my influences in a blender, what would add up to my playing would probably be George Benson, Django Reinhardt … I didn’t really like Django the first time I heard him, either, and then I just started learning it, because it was different. But also, on a technical aspect, the one thing that I did take away from learning the Gypsy jazz stuff was arpeggiating.

Guitars

Paul Reed Smith Modern Eagle II with vibrato arm

Paul Reed Smith 1980 West Street Limited

Paul Reed Smith Swamp Ash Special with 58/15 low-turn pickups

Paul Reed Smith Private Stock JA 15 with 58/15 low-turn pickups

Paul Reed Smith SE 277 Baritone Soapbar with flatwound strings

Paul Reed Smith Swamp Ash Custom 24 7-string

Amps

1976 Fender Twin Reverb

Bogner Shiva 20th Anniversary

Paul Reed Smith Archon

Roland Micro Cube

Effects

Electro-Harmonix Super Ego Synth Engine

Electro-Harmonix Freeze Sound Retainer

DigiTech Whammy

WMD Geiger Counter preamp and multi-effects

Cusack Tap-a-Whirl tap tempo tremolo

Dunlop Kirk Hammett Cry Baby Wah

Strings and Picks

D’Addario (.010–.046)

D’Addario flatwound (.012–.052)

Dunlop XL jazz picks, various gauges

Dunlop Yellow, Blue, and Purple Tortex

I don’t really play scales very much. I play scale fragments and arpeggios. I like playing changes because it’s not something a lot of faster guitar players do. They play fast, but they’re not playing to, like, heavily substituted IIm–V–Is and blowing Charlie Parker lines and stuff like that. That’s what fascinates me.

One of my favorites is [Dutch jazz manouche virtuoso] Jimmy Rosenberg. That’s the guy that I sound more and more like the more I play, ’cause I just love his playing so much. I like [Pat] Martino a lot, I’ve studied him quite a bit, but as far as an active guitar player that does it for me, nobody does it better than Jimmy Herring. He’s the guy that carries the torch right now. There’s something really cool about playing very borderline outside and then resolving it with something sweet and bluesy. I get a lot of inspiration from Jimmy, when it comes to just, like, “Let’s drive this off a cliff a little bit, then bring it back and resolve it nicely.” [Laughs.]

How did PRSs become your main guitars?

[When I started in bands] I was playing hollowbody PRSs. I saw it as an opportunity to do things that hadn’t really been done before. But not only for that reason. I thought that if I’m going to dedicate all my time to this, I’m going to do what I want to do. I don’t really want to sound like every metal player. I want to put Martino lines and Django lines over death metal. Because that hasn’t really been done, to my knowledge. And I want to play a hollowbody because nobody does in death metal. And so I did it. And that’s kind of what got PRS’s attention.

They didn’t really have anybody on their roster playing extreme metal on a hollowbody through a Rectifier. And that’s when Paul Reed Smith and I, our relationship kind of started. He’s responsible for encouraging me to be 110 percent myself. I’ve been with them for about 10 years now. The one thing that stuck was when people started saying, “You can tell it a mile away when you’re playing.” And I thought, “Okay, I got to keep doing what I’m doing.”

What artists influenced the sound of this album?

I’m a bit of a paradox when people find out what I listen to and that the goal was to put out a record that was like Django Reinhardt meets Depeche Mode … like Django Reinhardt meets Nine Inch Nails. Literally, I have never heard anything like that. You can probably hear some things that I didn’t really intend to put in there that are just part of my upbringing, like Nine Inch Nails. There’s stuff that you have to do as a guitar player to make a living—that you can be happy with but may not be creatively satisfying. This is definitely the project where I wanted to be creatively satisfied, even down to where the live shows happen. It actually can be presented like a jam band, where sections will be extended and solos will be improvised.

“The further you get away from playing, the more afraid you become of it, when it comes to playing onstage,” says Werstler. “When you’re out there playing 10 shows in a row, by the tenth show, you’re not nervous at all.” Photo by Perry Bindelglass

What’s your favorite track on the album?

I’m pretty much sick of every one of ’em at this point. [Laughs.] It does kind of change. I’m really happy with “Devil in the Room,” because it’s different. It was the last one written for the record. A lot of the actual recording process before the record was finished was taking things out of it instead of adding more. And I think that “Devil in the Room” is probably the most balanced song as far as the way it hits the speakers. But “Black Licorice” is probably the one that has the most vibe. It’s Jeff Beck-y, almost. I’m really proud of that one. But tomorrow it’ll probably be a different answer.

You’ve said narrative is important. What music today, in your opinion, has narrative?

The genres that have the fire right now are the experimental genres. A lot of the hip-hop guys are getting kind of psychedelic. And to me, these genres have the appeal, the mystique, the delivery, the message, the narrative—mainly because they don’t have to have 30 grand to pay for a record and have a band and get it to a rehearsal space. They can just show up, see something in front of their faces while they’re walking down the street, and it could be out on a mixtape the next day. That intrigues me, and that’s where I want to go in the future. I still am impressed by Death Grips’ No Love Deep Web. I can’t tell if they spent five minutes or five years on it. The beats are moving around, it’s not all quantized to the grid, it’s dark, it’s very unsettling. These guys are saying what they want to say—not just regurgitating what someone else is saying.

How do you challenge yourself to innovate on guitar?

I stay uncomfortable. I always work on my weaknesses and I’m very aware of my strengths, but my biggest thing is I try not to overthink things. I try to keep things almost reactive. For example, if I feel like sitting down and writing a song, I’m going to sit down and write a song and I don’t want to let up until it’s done. I also look back. I don’t really know what’s going on now in the guitar world itself. My head is kind of in the sand, and I pull from older sources. So if I feel like I’m not learning enough, I will go back and find bebop licks, I’ll learn Pat Martino, I’ll try to find things that work over certain chord changes that I would use.

Also, maintenance-wise, I go to jams quite a bit. I have to get out and play, because I do enjoy that. And the further you get away from playing, the more afraid you become of it, when it comes to playing onstage and live. When you’re out there playing 10 shows in a row, by the tenth show, you’re not nervous at all. But if you haven’t played onstage in a year or two and you’ve gotta go play with somebody like Brent Mason, it’s going to be nerve-wracking. [Laughs.] I just try to stay as active as possible and I’m very aware of my weaknesses.

How much do you think your personal philosophy shaped this album?I’ve always treated everything I’ve done like it’s the last thing I’m going to do. I think that philosophy did shape the music, because it took a severe amount of tolerance for me to put up with making a record this way. It represents getting it right. This was the first real one. Everything else was just me learning. I feel like I need to, not to sound cheesy, but, lead by example. Hey, if you got something to say, you better go say it. It’s all going to be a pain in the butt, so why not do what you want?

For a taste of Emil Werstler’s Django Reinhardt-inspired side, with a close-up on the fretboard of his PRS, check out this online lesson on Django-based chromatic lines. He makes it look easy.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)