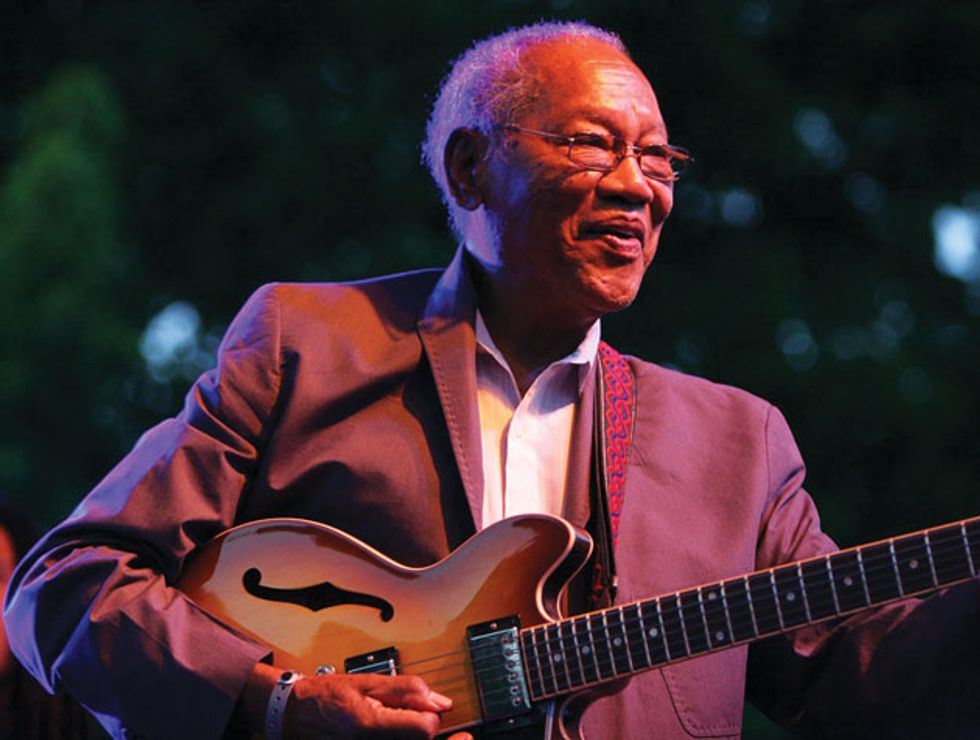

Ernest Ranglin is the Energizer Bunny of guitar. At age 82, the inventor of the mute-plus-upstroke “chank” rhythm that defines ska music has recorded a new album, Bless Up, that’s a summation of his visionary intelligence as a musician and composer. His playing on the disc is relentlessly perky, propulsive, and lush, proving that his mélange of chops—a vocabulary of jazz, reggae, R&B, rock, world music, and classicism—is as fluent as when he was a pup in Kingston, Jamaica, in the ’50s and ’60s, when his performances helped take the city’s famed Studio One sound around the planet and onto the international pop charts.

Although deep reggae and ska fans revere him, Ranglin’s 11 original tunes on Bless Up—where he’s supported by the core trio Avila—prove he deserves wider recognition. Always at the core of his playing, his jazz roots extend throughout the album. It’s not just a matter of Ranglin’s sound, which shares the warm rolled-back-tone-knob, flatwound strings, and humbucker tones of his contemporaries Wes Montgomery and Kenny Burrell (respectively born eight years and one year before Ranglin’s June 19, 1932 birthday). It’s the passion and taste he invests in cuts like “Follow On” and “Good Friends,” where he leaps gracefully between chord melodies, languid single-note lines, and quick-burn solos.

The scope of Ranglin’s writing is impressively wide-screened. His sweeping big band arrangement of the title track blends a reggae pulse with an orchestral sensibility similar to Duke Ellington’s, and “Bond Street Express” pushes the envelope toward the textural, spaghetti western fare of Ennio Morricone. And yet, there’s simplicity and an unhurried pace at the core of all this music that is pure Ranglin.

“I want people to understand what I’m playing, so I like to keep the melody present and anchor it with a good rhythm,” says the Ocho Rios resident from his American home base in Southern Florida. “These days, people aren’t looking to be challenged in their listening. You have to meet them halfway.”

Ernest Ranglin's Gear

Guitars

Gibson ES-335

Ibanez GB10

Amps

Epiphone EA-32 RVT modified with a 12" speaker

Ampeg VT-120 1x12 combo

Effects

None

Strings and Picks

D’Addario flatwound ECG26 Chromes (.013-.056)

Heavy picks—any brand

Ranglin’s mastery and perspective are self-acquired. He caught 6-string fever as a kid, inspired by the Jamaican folk music called mento and the recordings of electric jazz guitar innovator Charlie Christian. Ranglin learned to play by renting guitars and studying instructional books. He was still renting when he began gigging as a teenager in Jamaican big bands, which were inspired by American swing records. Eventually he earned enough money to buy a Harmony electric.

Ranglin was playing at Coxsone Dodd’s Studio One in Kingston, including sessions with a young Bob Marley, when he cut the rhythm track for pianist Theophilus Beckford’s “Easy Snappin’,’’ a 1956 song—unreleased until 1959—that transitioned the sound of the New Orleans rhythm and blues Jamaicans heard over the airwaves into a style of their own: ska. Ranglin’s arrangements for that tune and two subsequent singles under his name, including his famed instrumental “Shuffling Bug,” are the foundation of ska. And when he began working with Chris Blackwell’s fledgling Island Records in England, Ranglin made his ska beat the basis for the label’s first international hit: Millie Small’s sugary 1964 smash reworking of the doo-wop tune “My Boy Lollipop.” That single took ska to the world.

A half-century and a lifetime of touring and recording later, Ranglin’s memory is as crisp as his musical command, and he speaks in the same warm, relaxed, lilting manner that makes Bless Up such a pleasure to hear.

Much of your best-known music—from your ska defining single “Shuffling Bug” in 1959 to your arrangement for “My Boy Lollipop” in 1964 to “Surfin’ ” in 1996—has a rock and pop edge, but Bless Up is beautiful and unhurried, almost orchestral in its scope. What led you to that approach?

I’ve done so many things before, but these days you have to try to meet the people. Let’s put it that way. You can’t go too far out. I tried to make the album as simple and catchy as possible. Also, I like the tempos. I like to be sure the music is never rushed. What I love is finding certain musicians who have the feel for what I want to do. That helps a lot, because it’s not a long process for them to really understand it and play it the best that they can.I wrote songs for this album with the members of the Avila band in mind, because I’d already done one album with Avila, so we all knew each other well. It was easy the second time. They knew what I like and the tempos I enjoy, and I knew whom I was writing for.

Do you currently think of yourself mostly as a guitarist or composer?

I think I do more writing than playing, really, because most of my time is [spent] writing. Whatever comes to mind, I make sure I put it down.

Photo by Terry Way

Tracking a Legend

Ernest Ranglin’s Bless Up is an ambitious, well-realized summation of the veteran guitarist and composer’s musical vision, but for record label owner and producer Anthony Mindel, it’s also part of what he describes as “the ultimate experience—something I’ll cherish for the rest of my life.

“I’ve been listening to Ernest’s music since high school,” he explains. “I grew up in the Bay Area, and lots of ska and reggae gets played in Northern California. That music just seems to fit the lifestyle, and I certainly took it to heart. If I had to pick one style of music to listen to on a desert island, it would be Ernest’s, because it’s got the jazz, reggae, ska, and world music sounds I love.”

Mindel began working with Ranglin in 2011 when he assembled the aces in the band he dubbed Avila—also the name of his record label—to support the guitarist at the High Sierra Music Festival in Quincy, California. The resulting interplay inspired Mindel to take Ranglin and his new compadres to In the Pocket studio, nestled amidst the redwoods of Sonoma County, to cut 2012’s Avila.

“Bless Up takes their collaboration to a new level,” says Mindel. “I really want people to hear this album so they’ll know Ernest is still going strong at 82, composing and playing great music that touches on all eras of his career. Ernest showed up for the sessions with beautifully written charts—and they were handwritten, not done on a computer like all the charts you see today.

The album has a real analog integrity and the band sounds like they’ve been playing together for years. And while nobody knows Ernest’s music like Ernest, he was very open to suggestions from the other musicians.”

Ranglin’s playmates in Avila fit naturally into the guitarist-composer’s internationalist perspective. Bassist Yossi Fine is from Israel, drummer Inx Herman hails from South Africa, and keyboardist Jonathan Korty is a Californian.

“Working with Ernest and being his friend means everything to me,” Mindel relates. “It’s the culmination of all I’ve dreamed about musically, and I’m constantly inspired by his work ethic, virtuosity, humor, and generosity. We’d like to make more albums with Ernest for as long as he’s able to keep composing and recording.”

Photo by Tony Zucker

As a composer you combine elements of ska, reggae, jazz, rock, and textural music—sometimes in the same song. That’s paralleled in your playing, too. How did you arrive at that fusion of styles?

I started from traditional Jamaican folk music—mento. Then the first bands I played in were swing bands, so my interest in jazz grew. The two people who deeply influenced me after that were Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, and, after them, the great Mr. Coltrane. From there I went on to play Latin American music and R&B. But jazz was my biggest music after the swing era, and I heard all the pop, soul, and rock ’n’ roll on the radio. So I have a lot of commercial styles and maybe a little bit of a semi-classical style in my writing. Today I try to get a feel for whatever is going on in popular music, and try to present music to the people that they can relate to.

Jamaica is typically thought of as a land of rhythm, but your compositions are equally strong melodically. Which is most important to you as a composer?

I like to throw in an anchor, and that’s the rhythm. Then the melody should be as simple as possible, but it should have a little “oomph” to it. I like to experiment, but still be aware of having that anchor for the listener.

“Shuffling Bug” was one of the first ska tunes. What inspired you to come up with the rhythm guitar approach that’s the heart of ska?

That first ska record was [1959’s] “Easy Snappin’” by Theophilus Beckford. But I was the composer of the arrangement for that song, too, and started that type of rhythm. And the next ska tune I did by myself. That was [1961’s] “Silky.” And then “Shuffling Bug” came a week or two after that. Many people think it’s the first ska tune, but it’s not.

To explain how this rhythm was formulated I have to take you back to the very first person who influenced me on guitar—Cecil Houdini, who I heard in Kingston when I was a boy. He played this shuffle rhythm. The rhythm I developed is that shuffle rhythm, which is based on a New Orleans shuffle beat, where the first beat [or downstroke] is actually on the second beat.

What was it like growing up and trying to play music in Robins Hall, where you were born, before you moved to Kingston?

There was not much music. It’s in the countryside of Jamaica. I lived there until I was 9 years old. The first instrument I tried to play at that time was my uncles’ ukulele. A lot of people think they taught me how to play, but they didn’t. I’m self-taught. They didn’t want me to touch it. I would grab it when they went to work and I’d try to retune it, but I couldn’t tune it to pitch. I would tune it high, and when I finished I would try to tune it back. I didn’t really try to play the guitar until I was 14, and then I would buy books and study those.

Did playing in the popular big bands of Val Bennett and Eric Deans help you step into composing?

Yes, because working with a horn section helped me learn to phrase and seeing the charts helped me learn how to notate music, because in the books I was studying there were only chords—they just taught you how to strum, not to play lines like Charlie Christian.

Besides Charlie Christian, who among jazz guitarists influenced you?

Charlie Christian was the first one I heard, but Oscar Moore with the Nat King Cole Trio was also a fine guitar player. And Django Reinhardt came next for me. But I never really was attracted to too many guitar players. Once I knew a bass player who was fascinated with another great bass player, to the point where he could only play that other man’s style. That was not for me. I figured as a young feller I didn’t want to copy other people. I wanted to have my own style, so I listened to other instruments, like trumpet, saxophone, and even piano. And from there, I tried to define myself.

YouTube It

This 2012 clip from a live concert at Tokyo’s Blue Note features Ernest Ranglin in a band with three other prominent Jamaican artists: the quintessential rhythm team of Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare, and jazz pianist Monty Alexander. Ranglin’s playful sensibility shines throughout, from his beatific smile to the single-note blurts and over-the-top-of-the-neck fretting he tosses into the tune’s closing “duel” with Shakespeare.

Let’s talk about some of the guitars you’ve used on historic recordings and tours.

I had a later model Ibanez I used for part of the new album. George Benson gave it to me. I met him in France when I was playing at Montreux. I told him, “I would like to buy one of your models that you advertise,” and I knew that if he recommended me to Ibanez, I would get it a little cheaper. Instead, he gave me a guitar. I took that guitar to Senegal, where I went to do a record with Baaba Maal. Eventually, I gave it to the Jamaican Music Hall of Fame. I’ve given away many guitars. Sometimes I have as many as 20, but I end up giving away about half of them to charities or a museum. Sometimes I notice someone who can’t afford to buy an instrument, so I give them one of mine.

In the ’50s and ’60s I was using Guilds. I used to have an acoustic Guild, too. I still have a little Guild X-50 I bought from a guy in 1959—a lovely little thing. I also still have my Super 400, my Charlie Christian, my ES-175, ES-335, ES-339, and a few acoustic guitars. I have Fenders, too, but I prefer a hollowbody sound.

How do you get your super-warm tone?I prefer an Ampeg VT-120. You can get what you want from it. I don’t like a tinny, tinny sound. I can tune up the amp the way I want it. Of course, I also roll the tone pots back on my guitar. I generally use the dark side of the tone. I’m not a guitar player who bends and stuff like that. I like my guitar to sound mellow.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)