At the apex of Blur's mid-'90s superstardom, a casual listener could be forgiven for failing to hear Graham Coxon's guitar brilliance. Songs from Parklife and The Great Escape—records that virtually defined the cultural earthquake called Britpop—were so overflowing with hooks, brass, bubbling synths, radical song-to-song stylistic shifts, and Damon Albarn's characters writ in boldface that Coxon's fretwork could seem relegated to the sidelines.

But for those who listened deeper and looked beyond the mania surrounding Blur at the time, Coxon's hit-and-run shards of chord deconstruction, Fripp-fired leads, and impeccable sense of rhythm and timing were nuggets of pure musical treasure.

Like '60s British players who assimilated American blues and international influences to brew their own pot of gumbo, Coxon wed his love for unbridled American iconoclasts like Sonic Youth, Dinosaur Jr., and Yo La Tengo to a foundation built on the Smiths and U.K. indie, Canterbury prog, free jazz, krautrock, the Kinks, the Fall, and My Bloody Valentine. And his ability to channel those divergent influences via a vivid musical imagination and raw, instinctive virtuosity made Coxon a potent, protean, and artful guitarist in a British scene that could be pathologically regressive.

To fans who stayed on or joined anew for the post-Britpop LPs Blur and 13, or caught the band live, Coxon's skills became profoundly apparent. His restless sense of experimentalism blossomed and thrived on Blur and 13, as Albarn warmed to Coxon's American indie fascinations and the band embraced shared affections for dub, electronica, African pop, hip-hop, and folk. Blur's live shows, meanwhile, revealed that Coxon could move from Gilmour-scale grandeur to hardcore punk thuggery and unhinged sound sculpture—sometimes in a single song.

Like Nirvana a few years before them, Blur brought indie aesthetics and ideals to the masses, often with uncomfortable and unintended consequences. Yet for all the discord Blur's success stoked within the band (and among boyhood friends Coxon and Albarn, in particular), it led to fruitful creative tensions. Indeed, the sound of Coxon bursting at the seams—alternatingly weaving chaos, squall, and filigreed beauty around Albarn's pop ideas—became the backbone of much of Blur's most vital and enduring work.

By 2003, the white-hot energy that drove Blur consumed them. Coxon became a prolific solo artist, turning out eight superb albums (on which he typically played every instrument and part) that traded in lo-fi art punk, dynamite power pop, and fleet-fingered acoustic Albion folk. Albarn, meanwhile, took the post-modern fusion concepts hatched on 13 and ran as the multimedia phenomenon Gorillaz.

A 2009 reconciliation between Coxon and Albarn found Blur risen from the ashes. But as any viewing of that year's shows at Glastonbury or Hyde Park reveals, the reunion was hardly casual opportunism. Coxon was on fire. So were Albarn and the rest of the band. And the momentum born from the reunion carried through a 2012 London Olympics-closing show at Hyde Park and 2015's The Magic Whip—an album Coxon shepherded to completion using jams from a spontaneous but incomplete 2013 Hong Kong recording session.

More recently Coxon retreated to his attic studio to concoct the soundtrack to the Netflix series The End of the F***ing World. And while the inherent constraints of a soundtrack meant that Coxon couldn't always indulge his most spontaneous and radical urges, it is full of unexpected, genre-hopping turns that attest to his wildly eclectic influences, multi-instrumental virtuosity, and voracious love of music and visual art. There may be flashier guitarists, or more conventionally masterful ones. But few players in pop history can match the resourcefulness, imagination, and irreverent vision of Graham Coxon.

Coxon and Damon Albarn began playing together as schoolboys in Essex, England. The telepathy, brotherly affection, and creative tension between them is a cornerstone of Blur's most vital and enduring work. Photo by Lindsay Best

Impressively for a soundtrack that has so many textures, you scored The End of the F***ing World music by yourself in your home studio. How did you approach the prospect of a blank slate every day?

Well, it's so much easier these days to record in your spare room. I've got a house now where I knocked everything out in the attic, and I've just been collecting things over the years. I started out buying Logic and got a little Focusrite two-input desktop interface. I learned Logic and did a song for a movie called The Riot Club with that setup. Before then I'd never worked with digital audio workstations, I just demoed things in other ways. But I watched a bunch of YouTube, figured out whose advice I should be listening to, and just got a couple of key pieces of gear.

Now I have quite a few channels to work with. I have some odd consoles—a strange old Glensound BBC console, an old Trident Fleximix, a few BAE 1073 Neve-style things, some nice API lunchbox EQs, and a lovely Chandler germanium compressor. So I just got a few bits that I can really do stuff with, and it's surprising how easy it is to make voices and guitars sound the way they should sound working in the attic. I can't really do drums too loud, so there's a combination of drums and heavily tweaked Logic drums on the soundtrack. But it's pretty amazing what you can achieve in your spare room, just out of bed. You can play when the inspiration is there and come up with fairly interesting stuff when you're half asleep. I love it.

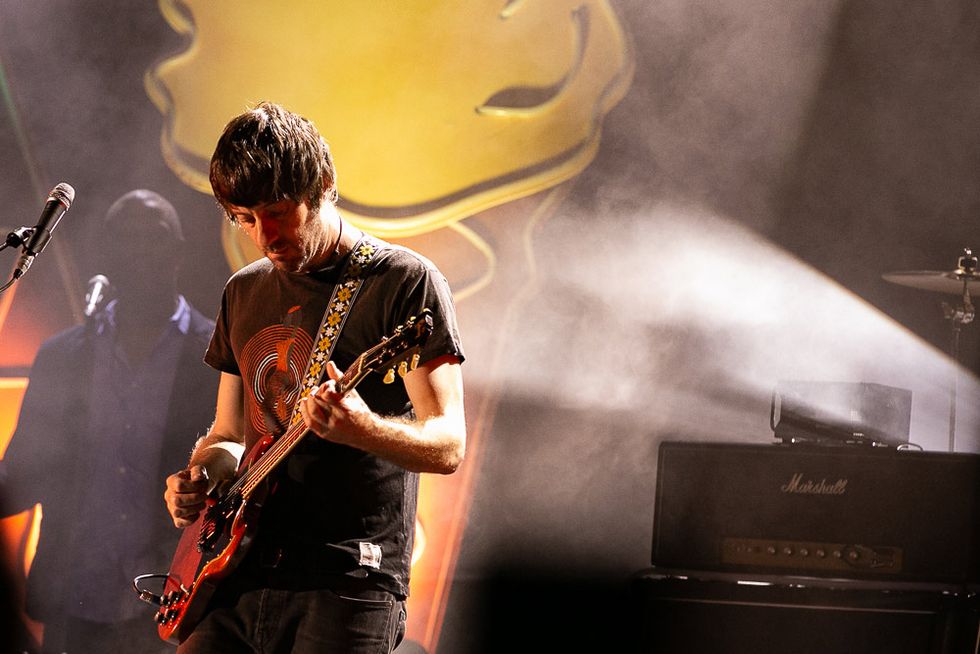

Coxon started using his early-'70s Telecaster Deluxe around the time of his power-pop-driven LP Love Travels at Illegal Speeds. But it became his primary Blur guitar for the 2009 reunion—adding a ragged muscularity to the sound of many Blur classics performed on that tour. Photo by Jordi Vidal

Did you follow the script and your instinct in equal measure or was there more specific guidance?

I had scripts and a couple episodes that might include temps [songs chosen by the director to suggest a specific mood and stand in for actual soundtrack music]. So I'd listen to the temps, figure out what it was giving to that scene, and come up with three or four things that were sonically similar. Or I might have a little list of ideas or things required for an episode and I'd do three or four versions of those. But then I'd spend the rest of the day fiddling with stuff that wasn't in the brief. That's how “Walkin' All Day" came about. I just sat there fingerpicking, which is what I like to do when I'm just sitting around. Those kind of songs, those country blues songs, come quite quickly for me. That wasn't part of any brief. I guess I just saw the kids walking along in my head.

But I like working like that—getting a theme and then flogging it like a dead horse. In this case just walking all day and feeling like you're on fire because you're feeling strong emotions. That came out of nowhere and became the song everyone initially reacted to. And I thought, “This is amazing! I can write a song in like 40 minutes, and record it upstairs, and have it work." I tapped on one of those boxes you sit on and hit with your hands, added some kick drum, some tambourine, and some slide, and it was done. I'm not the best slide player in the world and my guitars aren't really set up for slide, but it added to that clunky kind of sound, and gave it a sort of London, Muswell Hillbillies kind of feel.

Country blues was far from the only sound you conjured on the soundtrack. “On the Prowl" has an almost Oh Sees feel. “In My Room" made me imagine Ray Davies sitting reluctantly on a Malibu beach—sort of a melancholy English surf ballad.

Yeah, well I've definitely done that—sat on a beach in Malibu thinking, “What am I doing here?" [Laughs.] “On the Prowl" and “The Snare" have that swampy kind of feel—it's a bit of the David Lynch sort of thing. But one of my favorite references for that swampier stuff was Link Wray. When they needed a theme for the detectives, I thought it would be quite fun to have a swampy Link Wray, lilting, 6/8 sort of thing. It's tricky to make things really sound like something from 1958. But I just used spring reverbs and my old Fender Bass VI—I played a lot of stuff on that riff monster. “In My Room" was definitely some Scott Walker influence. I'm a huge Scott Walker fan. There's another song that wasn't actually included on the soundtrack that's in that vein, which I actually think is the better song. Maybe it'll come out down the line.

It's really cool to hear you sing down in that Scott Walker range.

Well, that's what's so fun about recording on my own. I didn't have to be embarrassed. I could be whatever character I wanted to be. I was pitching my voice to do feminine voices.

Then I had to do quite a few punk rock numbers, so I'd just put a quilt over me and get an SM57 and shout. But if I was doing a more Scott Walker-style thing, I would get a bit more classy about it—put up one of my posh microphones and get a nice reverb going. My normal way of singing is a product of me being shy with a producer. But I'm learning to try more stuff out.

Guitars

'70s Fender Telecaster Deluxe

'60s Fender Bass VI

'68 Fender Telecaster with Gibson PAF in neck position (inspiration for the Graham Coxon Signature Fender Telecaster)

'67 Fender Jaguar

Fender Custom Shop '60s Telecaster reissue

Fender American Telecaster Custom reissue

'62 Fender Jazzmaster with '61 Jazzmaster neck

Fender Stratocaster (assembled by Steve Prior from various Strats, including a neck that belonged to Jeff Beck)

Early '60s Gibson SG Special

'80s Gibson Les Paul Custom

'80s Gibson ES-335

Gibson goldtop Les Paul

Ralph Bown OMX

Atkin OM

Amps

'90s Marshall 1959SLP Super Lead

Marshall Power Brake

Effects

BAE Hot Fuzz

Wattson FY-6 Fuzz

Shin-Ei FY-2 Companion Fuzz

Pro Co RAT 2

Pro Co Turbo RAT

Carl Martin Echotone

Origin Effects Cali 76 Compact Deluxe

Thorpy FX Fallout Cloud

Xotic EP Booster

Boss BF-2 Flanger

Boss PH-3 Phaser

Boss VB-2 Vibrato

Boss TR-2 Tremolo

Hudson Electronics Broadcast

TC Electronic Alter Ego

Suhr Koko Boost

Line 6 FM4

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball .010-.052

Dunlop Nylon .73 mm

Do you enjoy working in solitude? It's so different from having a band and a producer looming over your shoulder.

I do like it. There's pressure once you get in a typical studio situation. Time is running out every day and the clock is ticking. With this sort of thing I can work hard at it, but at my leisure. And you can come back to stuff more easily, use every idea, and move through a lot of ideas quickly. Plus, I can go up to the studio 10 minutes after I've woken up and before my old habits start popping up. Something totally different than the norm can happen then. As a guitar player—especially when I'm playing in standard tuning—my hand habitually goes certain places. And I hate that. I'll do anything to avoid that.

Did The Magic Whip, and the role you had in its production, inform your approach to the soundtrack? You've done so much solo stuff, but in that case, you were shouldering the burden of guiding a Blur album from raw sessions, pleasing your bandmates, and living up to expectations and the quality of the band's canon. That's a lot of responsibility.

It wasn't a huge responsibility, really. I got Damon's blessing and just said, “Gimme a go and if it don't work, we can bin it." There wasn't a lot of pressure because no one really knew about it. But it did give me a lot more confidence, especially in my ability to work quickly and that when presented with a monotonous jam session—where the same idea is played over and over again—I could arrange it and write new parts that will fit, or use a new chord that will go around a melody line that already exists, or find a new melody for a chord progression that's in place. You're reminded that there's a lot of ways things can work out.

People that really understand music theory would hear me say this and go “duh!" But to me it's still a revelation—the atmospheric or emotional change you can get by going to a relative minor or major while still supporting an existing melody. It was also very much about the rests and pauses within a song. The thing about The Magic Whip was that I got to do all my favorite things I love about songwriting. The basic music was already there. I just had to find a way to arrange it and structure it, so it was dynamic and exciting. It worked out well enough that Damon said, “Wow, bloody hell!" and had to resign himself to the fact that he was going to have to sing on it. [Laughs.] But it was nice to play such a big part of that record as a way of making amends with my long-suffering bandmates.

One of the running themes among your Blur bandmates in discussing The Magic Whip is a real sense of wonder and gratitude at your restraint as an arranger and player. Was that a conscious mindset?

Well, I had to put on a producer's hat and figure out what a song really needed instead of putting stacks of distorted guitars on. That was just not going to work. A lot of the material was quite sensitive. I like space and I like restraint. I'm a bit older now and I do like mellower music. And I'm always interested in different sounds and textures. Things don't always have to have some awesome impact, either. They can be simple.

Was the solo in “Go Out" a carryover from the Hong Kong sessions? It sure has that sense of hectic claustrophobia you'd associate with the city and that cramped studio you were in.

Yeah, definitely. That was there [from the original Hong Kong sessions]. There were bars and bars of that stinging, horrid, anxiety-inducing guitar. But I think that Hong Kong trip was my last hurrah as a self-centered brat. That attitude seemed to die off a bit after that. That was always my role in Blur, I suppose. I was aware of that change in me. But when people heard The Magic Whip and it wasn't covered in guitars, they must have been quite shocked. [Laughs.]

Coxon's '60s SG Special first turned up around 2004's Happiness in Magazines solo LP. After the Blur reunion it became Graham's vehicle for the viscous live versions of The Magic Whip's “Go Out" and the tender and wistful ballad, “My Terracotta Heart." Photo by Debi Del Grande

That honk you get from your SG in live versions of “Go Out" is a great sound. I hear the influence of the baritone and tenor sax players you dig in that tone.

I really like the idea of a note that moves through a whole chord sequence. There's one of those in there—that just pokes at you through the whole thing. I think there's some slapback echo and my SG, and some RAT distortion. There might be a tiny bit of reverb. But yeah, I do love a saxophone.

You're a big fan of a lot of post-bop and free jazz players, and quite a good saxophone player yourself. As a guitarist, do you instinctively or consciously work with the sound palette and freedom of the jazz musicians you admire?

Well, a lot of that freedom in the playing comes from art school. The guitar is my favorite paintbrush. But, yeah, I'm a sax player as well. Ornette Coleman, Jackie McLean, and John Coltrane—those are my people. I really love the period when the bebop stuff started to become free jazz. But it's a collection of things. I love Syd Barrett too, and that idea of big, bold brush strokes, which is really a very American Abstract Expressionist, New York school, Willem de Kooning-style approach to guitar.

Yo La Tengo and Pavement were also great encouragement to do whatever I wanted when I had the space. And weirdly enough, I never cared what anyone thought when I was doing that brash guitar stuff—which is really unlike me. But musically, I loved that sort of New York insanity. There was a great [English TV arts program] South Bank Show episode about the New York scene and Sonic Youth and John Zorn. I loved Sonic Youth, and I'd listen to Spy vs Spy, which was John Zorn's hardcore approach to Ornette Coleman. Then of course Pink Floyd's approach to loose psychedelic improvisation, too. I just concentrated on trying to get all that in one place.

That also led to places where I wouldn't try to do too much—just let the guitar talk through pedals. There's an amazing song on Yo La Tengo's I Can Hear the Heart Beating as One, “We're an American Band." I love the guitar solo at the end—it just takes off and gets more formless and drenched in distortion and reverb. It's a very free and a very American approach that was really inspiring. And there just wasn't much of that going on in England at the time.

On the flip side, while the popular perception of Graham Coxon is often tied to the anarchic aspect of your creativity, you also fit in the tradition of George Harrison or Johnny Marr—chord players who blur the roles between rhythm, lead, and songwriting—which really takes discipline.

It's kind of out of necessity, isn't it? So many guitar players I admire had to do all those jobs. Pete Townshend—my gosh, I haven't even mentioned him, he's such a huge influence—he had to do all those things in the Who. But yeah, just making little changes within the chord you're playing. I mean, I am a rhythm player really, but I can't just stand there strumming. I'd die from boredom. So I tend to move my fingers around and riff a lot within rhythm chords, using little hammer-ons and bends in the chord just to entertain myself. And I suppose that's really how you develop your own style and touch. It just comes from playing a lot and having to please yourself.

But things always had to reflect the drive of the song, as well. In Blur I had to channel Damon and interpret what he was getting at from a melody line, or the tempo, or his tone of voice—often before there were lyrics to latch onto. So as a song came together in the studio, I would have to generate ideas that supported those emotions pretty quickly and try different things over and over until Damon would get excited and go “yeah, yeah, yeah!"

That's been my role for such a long time and I really like that. It's exciting. I can't really sit there and shred and impress people with technical playing, but I can come up with things that back up the emotion of a song.

I recently listened to The Great Escape, which probably marks the high point of Damon's pure pop explorations with Blur. And oftentimes it seemed that the poppier things got, the more inventive your playing became. Did you relish the challenge of working against those pop structures?

Well, I knew I didn't want to just strum. So sometimes I'd try to come up with angular stuff, if it fit the mood of the song. I mean, the simplest example of that is “Girls & Boys" [sings rhythm guitar riff], which is me just being deliberately awkward because I knew it was going to be a very dancey tune.

But really, I was just having fun! Trying to fit all the ways of playing an A chord in one bar [laughs]—things like that. And I was so inspired by that American stuff—watching people like Steve Malkmus play, he was so free when he played. There was a lot of humor and mischief behind it too. Maybe that's the one difference between my playing and some of the American stuff I admired. I can't put up with too much intensity before I have to make a bit of a joke. So I would throw in something daft or purposefully cliché. It's really my weird personality crammed together with all this music in my head that I can reference. It's all stuck there, and then you come across a chord, or something in the melody reminds you of something, and out comes that file from the cabinet. That's just how my brain works.

Blur went through some real ups and downs in the early days. The label nearly dropped you around Modern Life Is Rubbish. Those seemed like stressful times, but they were pretty mind-boggling in terms of Blur's stylistic growth. You guys got very hot and prolific right around then. How does business affect creativity in those situations? In a way, you're playing for your life.

I always sort of played for my life, really. But I was blissfully unaware of what trouble we were in. It was insane, 1992. We were ripped off and had been mismanaged and owed loads of money. We thought we were going to be thrown in jail. But we also thought the work we were doing was really good. So we went on those two insane tours of the States. That was a big shock to me. We had two months, out with my friends, with no one around to tell you what to do. Flipping heck! In two weeks I was crying—I didn't even know why. [Laughs.] I was such a state, because no one warns you and says, “If you carry on like that, you're going to have a nervous breakdown." I didn't have the voice of Keith Moon coming down from the heavens saying, “Graham, you must stop being such a maniac!"

So that was really just youthful energy and creativity driving all that output. Even the B-sides from that time are superb songs and sonically inventive.

Yeah, we were crazy, just creating and creating and creating. We'd work on the B-sides late at Maison Rouge studios all on our own without a producer. We'd stay up all night working on things like “Oily Water" and “Resigned," which made the album, and then things like “Bone Bag" and “Peach," and a bunch of other stuff that didn't make the record but are among my favorites. But [to Food Records label chief David Balfe] that was all weird shit, and we were getting yelled at to come up with a single. I just thought “Yeah, whatever." But Damon was really under pressure to come up with the goods. And he did. “For Tomorrow" and “Chemical World" really saved our bacon. Our American label didn't like Modern Life Is Rubbish, though ... [incredulously] they wanted us to re-record the whole thing with Butch Vig. Which might be interesting now, actually. [Laughs.]

At that point, you guys were also having a really good time. I've been told Blur was the life of the party on the Rollercoaster tour. [The now near-mythical Rollercoaster tour featured Blur, My Bloody Valentine, Dinosaur Jr., and The Jesus and Mary Chain.] I can't imagine that many people who saw those shows realized how legendary that lineup and the guitar players involved would become.

I know! It was flipping amazing. These were my favorite people—the people I was listening to anyway. And suddenly I was standing onstage while they were soundchecking. Not for long though, jeez—they were all flipping loud. It seemed like Dinosaur Jr. wouldn't really play a song for soundcheck; they would just make as much noise as possible. But I absolutely loved J's playing and loved Murph's drumming. I was in heaven every night.

We were the insane puppies on that tour. The other groups were a bit older. They must have thought, “My god, will these guys ever shut up and stop wagging their tails." But it was a very rock 'n' roll tour and I had a lovely time—hanging out with My Bloody Valentine, who I absolutely worshipped. Sitting having a smoke with Deb [Googe, bassist for My Bloody Valentine] and then, “My god, I'm sitting here with Kevin Shields and Belinda Butcher. This is insane." I was freaking out. I think a lot of the audience thought we were too poppy. But we were really doing our best to be horrible and noisy.

Of course, you're also a really dedicated folk and fingerstyle player. You contributed to some of the records and shows celebrating Shirley Collins and Bert Jansch. And you took on a pretty challenging, long-form fingerstyle-and-vocal piece in covering “Cruel Mother" on the Shirley Inspired tribute LP.

I know. I ended up cursing myself when I had to play it live. “Why didn't you just strum like everyone else?" [Laughs.] I also played a couple Bert Jansch tribute shows that were really scary, because playing Bert Jansch's stuff is not easy. I was nervous as hell. But yeah, for a while there I got really obsessed with under-saddle pickups and internal microphones going through blend mixers and EQs. I was really into the idea of getting an acoustic guitar and a little bag and going to America and playing weird bars, which never happened, but one day, I hope. I'd love to do that some time.

Essential Graham Coxon

In this 2012 Hyde Park take on the Parklife stomper “London Loves," Damon Albarn's pop sensibilities and Coxon's avant 6-string proclivities clash to a point of perfect symbiosis—especially at 1:43 where Coxon channels Zoot Horn Rollo and John Coltrane.Captured at Blur's intimate 2009 Colchester homecoming concert, this stage-right heavy, fan-shot take of The Great Escape's “Charmless Man" showcases Coxon's brawny Townshend-inspired hybrid rhythm/lead style and love of Super-Fuzz and RAT distortion.

With a Ralph Bown OM in hand, Coxon delivers a literal and lovely take on the notion of English bedsit folk—as well as a crafty homage to Davey Graham and Syd Barrett—with a cut from his 2009 LP The Spinning Top.

Always a willing and able shape shifter, Coxon and his early-'60s SG Special move from filthy funkateer, to clanging, sci-fi sonic generator, to Fripp-fried soloist in the space of The Magic Whip's lead single, “Go Out."

![Rig Rundown: John 5 [2026]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62681883&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C45%2C0%2C45)

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.