AM.PM, the intriguing all-instrumental release from legendary guitarist/producer Phil Manzanera and equally legendary saxophonist Andy Mackay, is full of unexpected twists and turns. “Somebody said to me recently, ‘I can tell you what it’s not. But I cannot tell you what the hell it is,’” says Manzanera. “And I quite agree. I listened to it and I’ve got no idea what’s coming next. I played the backing tracks once and I could never play it again. I’ve got the chord progressions…. Where did they come from? Instrumental music is a different kind of experience. When you listen to it, you tend to float off into your mind and just drift. There’s a visual aspect to it, to where you’re listening to it. It’s a wonderful, very different experience.”

Manzanera and Mackay have a telepathic working relationship, which shouldn’t be surprising, given they’ve made music together for over half a century. They first connected in 1971 as part of art-rock pioneers Roxy Music, alongside singer/songwriter Bryan Ferry, synth player Brian Eno, bassist Graham Simpson, and drummer Paul Thompson. Roxy Music went on to influence the sound of popular styles that later emerged, like new wave and glam rock. While the band members went their separate ways in 1983, Manzanera and Mackay worked together in various projects, including the Explorers, who were active in the late ’80s.

Mackay also played on Manzanera’s influential solo debut Diamondhead. And in addition to his solo career, Manzanera went on to perform with prog-rock cult heroes 801, has done session work, and, in 2006, began a collaboration with Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour, producing the latter’s solo album On an Island and playing onstage with Gilmour for several years, being a part of the Live in Gdańsk concert recording. Roxy Music reunited in 2001 and have toured sporadically since. On March 29, 2019, Roxy Music was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. However, only a few months later the Covid pandemic set in, paving the way for AM.PM.

Manzanera Mackay - "Blue Skies"

“During lockdown, everybody was sort of stuck at home, and most musicians, artists, and photographers were wondering ‘What the hell can we do?’” says Manzanera. “So I was in my garden shed thinking, ‘I need to do music to get through all this.’ I reached out to Tim Finn, the singer from Crowded House and Split Enz, and we started writing songs—loads of songs. And then halfway through, I thought, ‘You know what, I’d like to do something crazy. Nothing to do with songs and structures and stuff like that. I’ll ring up Andy, I’m sure he’s not doing anything [laughs]. I’ll tell him, ‘Get off your ass, we’re going to do some music, and it’s gonna be crazy music. I’m just going to do random stuff, send it to you, and you do random stuff, then send it back to me. We’ll just have no rules, no structure.’”

Music by Painting

With a nebulous concept guided by a “no rules” approach, AM.PM slowly developed over the course of two years. A diverse cast of musicians—Anna Phoebe on violin, Seth Scott on flute, George Goode on tuba, Paul Thompson on drums, Yazz Ahmed on flugelhorn, and Mike Boddy on bass/programming/keyboards—was recruited. They did their parts remotely, sending tracks via email. Manzanera would select and layer bits and pieces into Logic, improvise to it, and then send the updated files to Mackay for his input.

“Instrumental music is a different kind of experience. When you listen to it, you tend to float off into your mind and just drift.”

“It’s like a sort of call and response, but via Zoom, email, or phone. It was a good starting point for me on some of the songs—the ones with the violin, tuba, flute, and the flugelhorn,” says Manzanera. “Those were methods of initiating a track by saying, ‘You just improvise whatever you feel comfortable and I will then make a track out of it.’ I didn’t want anything particularly complicated. What I wanted from them was the beauty of their instrument, the tone of their instrument. And then I wanted to hear that set against the beauty of Andy’s sax tone or combinations of my guitar against a bit of tuba or French horn. It was a series of experiments. I thought, ‘Well, I haven’t heard this before with me, or with me and Andy, so let’s have a go and see what happens.’”

To get what he envisioned out of the musicians, at times Manzanera had to push them far beyond their comfort zones. Classical musicians are among the most highly capable of instrumentalists, and can often read even the most ink-filled pages of music with ease. But if you ask them to improvise, that skill set is sometimes out of their wheelhouse and they’ll freeze up. “I asked the guy who played some tuba to come and play a little bit at the end of one Finn/Manzanera song, and he’d done that. But he played the part very rigidly. Not ‘rigid,’ but you know, the way it was meant to be played,” recalls Manzanera. “And I said, ‘I’ll tell you what, can you now just improvise for one minute. Do whatever you like. Just play whatever you like, I will make a track out of whatever you play.’ Obviously, most classically trained musicians do not like to do that because they like to see dots.”

Phil Manzanera's Gear

Phil Manzanera plays his beloved Gibson Firebird VII onstage with Roxy Music in 2022.

Photo by Tim Bugbee/Tinnitus Photography

Guitars

- 1964 Gibson Firebird VII

- 2001 Gibson Black Les Paul Custom

- 2001 Gibson Les Paul Custom Gecko

- 1983 Fernandes Strat

- 1951 Fender Telecaster

- Gibson Les Paul Studio

- Fender Strat

Amps

- Two Cornell Voyager 20 heads (main and spare)

- Fender Blues Junior (for solos, with an SM57)

- Universal Audio OX Top Box (stereo return configuration, adding room and ribbon mic modeling on a Fender Bassman)

- Grossman FATBOX isolation cabinet (with a Celestion G12M, with an SM57)

Effects

- Two GigRig G3 controllers

- Two TX RX boxes

- JAM Pedals RetroVibe

- JAM Pedals Harmonious Monk

- JAM Pedals Wahcko

- JAM Pedals Fuzz Phrase

- Fulltone OCD

- TC Electronic Polytune

- Eventide H9

- Strymon TimeLine

- Catalinbread Topanga

- DigiTech Whammy

Strings & Picks

- Ernie Ball Super Slinky (.009–.042)

- Dunlop Custom Roxy Music Tortex Standard

- Vovox Sonorus Cable

The tracks on AM.PM aren’t beholden to traditional concepts of form, like intro, verse, and chorus. Rather, everything just evolved organically. “You give into the structure that exists there,” explains Manzanera. “You look at it—and you can, because if you work on Logic on a computer, quite frankly, you can have a visual view of the thing. You can color up certain sections. You can say, ‘When it goes into the purple, I’m going to play whatever, and when it goes into blue, I’m gonna just go like this.’ So it’s not painting by numbers. It’s music by painting.”

“I tried to send my Firebird to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame for them to put up in their museum and they were refused an import license.”

Manzanera’s primary brush was the trusty red Firebird VII that’s been his main guitar for decades. “It’s been my signature guitar, if you like, since I bought it secondhand from an American guy in London in 1973,” he says. “His parents had bought it for him from the factory in Kalamazoo, in cardinal red, which was a custom color. It was the color of a Ford Galaxie ’60s car, because Ray Dietrich, the guy who designed the Firebird, used to design cars. Gibson hired him because he was a car designer and they wanted to compete with Fender. He came up with the Firebird, but obviously it wasn’t as successful. But I loved it because it was red. The pickups are pretty unique because you’re not allowed to use that kind of metal—god knows what’s in it, it’s probably killing me or something. The wood you’re probably not allowed to use. In fact, I tried to send it to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame for them to put up in their museum and they were refused an import license [laughs]. It’s banned! I don’t know what kind of wood it is because it’s been painted red on top. I said, ‘It was made in America. What do you mean I can’t send it back to America?’”

Manzanera and Mackay approached AM.PM with very open minds. There was no agenda going into it, and, during the recording process, anything was fair game.

Partners in Crime

The back-and-forth between Manzanera and Mackay was relatively frictionless— without many, if any, disagreements. “We’re like mindless people,” jokes Manzanera. “The thing is that we have played together on and off for 50 years. I like what he does. He likes what I do. I find the spaces around him, he finds the spaces around me. It’s about creating a beautiful picture, a sonic picture. And when it’s done, it’s done. There’s nothing to prove here. We’ve made lots of music, we’re just trying to do something beautiful that satisfies us. We’re simple players. We’re not jazzers; it’s not about technique.”

AM.PM was still a work in progress when the Roxy Music 50th Year Celebration tour suddenly popped up in 2022. Manzanera and Mackay got detoured from AM.PM and had to divert their attention to bringing their chops back up to speed for the shows. Manzanera says, “Me and Andy spent ages practicing. So at the end of the tour, I thought, ‘Why don’t we just go into the studio straightaway and finish off that instrumental album now that our chops are really sort of up to speed.’ So me, Andy, and Paul went in for just three or four days and finished the album off, capturing that moment in time. It was trying to incorporate stuff that maybe had been played by humans and by machines, but then coming back and putting humans on top of it again. Of course, now I haven’t played since we finished it, and I’m rubbish again [laughs].”

“It’s about creating a beautiful picture, a sonic picture. And when it’s done, it’s done. There’s nothing to prove here.”

Beauty in Simplicity

Most instrumental albums released by guitarists will bludgeon you over the head with nonstop 6-string in every nook and cranny. But Manzanera’s never been about guitar pyrotechnics. And his “technical limitations” turned out to be a blessing, in a way, because it led him to explore a more probing and introspective guitar style. “The great thing is that I wouldn’t have played anything more [on AM.PM], because my technique is limited. And I wanted it to be limited because I wanted to enjoy playing music for the whole of my life. I didn’t want to learn everything. And quite frankly, I haven’t learned a lot,” says Manzanera, laughing. “I tell my younger self to ‘Put your batteries in, mate,’ because you should have actually learned a bit more technique.”

While Manzanera loves hearing other people play virtuosic guitar, that’s not the path he chose. “I just want to place notes and hear musical sounds,” he says. “This might be sacrilege to a lot of people, but scales are sort of a dangerous road to go down. I know you’re meant to do it. But I don’t do it. And you know, Robert Fripp would probably turn in his grave because he is incredibly good technically, and when I hear him play, I think, ‘Wow, that’s amazing.’ But I don’t want to be like that. I’d rather be like the Captain Beefheart school of mad guitar.’”

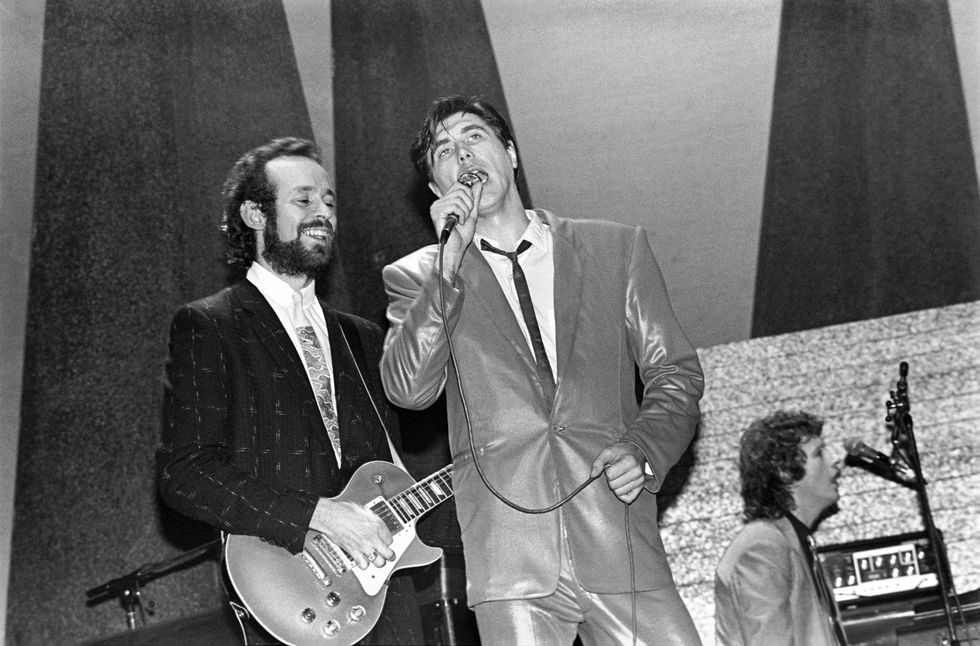

In the early days of Roxy Music, Manzanera mixes it up with Bryan Ferry—and a goldtop Gibson Les Paul.

In the early days of Roxy Music, Manzanera mixes it up with Bryan Ferry—and a goldtop Gibson Les Paul.Photo by Ebet Roberts

Expect the Unexpected

Manzanera and Mackay approached AM.PM with very open minds. There was no agenda going into it, and, during the recording process, anything was fair game. “When Boddy was mixing it, there was this really annoying sound from the drain pipe outside so he recorded it and added it into the track,” says Manzanera. “So I said, ‘Let’s call it ‘Music for French Horn and Drain Pipe.’” That track was later released as an additional album track along with “Lady of the Lake,” an adaptation of a Schubert classical piece.

During the late ’60s, prior to Roxy Music, Manzanera had dipped his toes heavily into improvised music, and that forward-thinking approach permeates AM.PM. “What’s sort of interesting is if you’re working individually like this and you’re not all in the room playing, you haven’t got that possibility like, say, the great Miles Davis with his fantastic quintet. Where you’ve got five incredible musicians and they are sort of improvising, and calling and responding to each other,” says Manzanera. “But because I loved all that kind of music and the whole influence of improvisational stuff in the ’60s, I’m comfortable with that. I embrace that kind of thing. So, when I’m not having to work within song structures, this is the nearest I get to being in that kind of Miles Davis free world.”

“Robert Fripp would probably turn in his grave…. But I don’t want to be like that. I’d rather be like the Captain Beefheart school of mad guitar.’”

“Blue Skies,” the album opener, and tracks like “Ambiente,” immediately strike a nerve with some jazzy, jagged dissonances not dissimilar to what you’d hear in Davis’ music. But Manzanera hears things differently. “You know, dissonance is not necessarily dissonance to me,” he explains. “After all a lot of the music making is a series of choices. ‘Do I do this? Or do I do that? Okay, if I do that, what do I do next? And then, is that it? Do I stop there?’ And all those choices come from your musical DNA—all this music that you’ve listened to. In my musical DNA, I’ve got Captain Beefheart, I’ve got avant-garde jazz. And obviously, mine is different to Andy’s and it’s different to Paul’s. So it’s the way people interact together sometimes. Even though they might play simple things, it adds up to something more than just one person’s idea.”

Full Circle

Having achieved legendary status, at this point, Manzanera can make music without worrying about having to cater to corporate overlords. “It means, I’m able to put out albums like AM.PM,” he says. “It’s all cottage industry, we don’t have multi-nationals with us. We’re free and that makes me happy. The whole point of being a musician was to be free, not to be told what to do by some global company. It’s the hippie thing, I guess from way back in the ’60s. We got brainwashed by that [laughs]. ‘Hey man, I just want to be free.’”

Manzanera’s Failed Audition … for Roxy Music!

Brian Eno was already an established figure in Britain’s avant-garde music scene when he decided to begin writing pop music and form a rock band. He had already found singer-songwriter Bryan Ferry and saxophonist Andy Mackay, and they had been working on demos for about nine months when they put an ad in Melody Maker, a now-defunct music magazine, looking for a guitar player and a drummer. Manzanera and drummer Paul Thompson, answered the ad. However, Manzanera failed the audition.

“I had a terrible cold that day, but actually, we got on really well, and I thought these guys are really special and different,” recalls Manzanera. “But they were kind of looking for someone with a famous name to help launch the band. They got a guy called David O’List, who had been in a band called the Nice—who toured in America already. They were on the famous tour with Jimi Hendrix and stuff, and early Pink Floyd—and they thought, ‘Right, actually we need to go with the name.’”

While disappointed, Manzanera didn’t really argue with that decision. “When I heard he got the gig, I thought, ‘Well, fair play, because he’s great.’ I saw him play at the Albert Hall with the Nice. This guy’s really good,” reflects Manzanera. As time went on, fate slowly intervened. “Things [with O’List] didn’t work out because, I think, on the first tour that he did in the States, he’d been spiked with some acid so he was just like ‘away with the fairies.’ And they couldn’t cope with his not turning up on time and things like that.”

When Roxy Music brought Manzanera back into their world, it was somewhat on the sly. “They said, ‘Oh, do you want to come and mix the sound?’ And I said, ‘I’ve got no idea how to mix the sound.’ They said, ‘Don’t worry, Eno will teach you.’” And when Manzanera turned up to the rehearsal room, mysteriously, there was a guitar lying around, and they asked him to play. It was, in effect, a secret audition.

“That was a good idea,” says Manzanera. “I probably would have been nervous. But then, you know, I joined, and then a week later, we signed the first contract. And a month later, we were recording the first album, six months later it was number four in the charts. So I was just in the right place at the right time. You know, lucky them because they could have not had me [laughs]. You gotta laugh really. It’s fate.”YouTube It

Phil Manzanera is a proponent of the “less is more” approach. Throughout AM.PM, the guitar is used as only one piece of a bigger compositional puzzle. In the haunting “Newanna”—written around violinist Anne Phoebe—the guitar is used very sparingly in the opening section, mostly to add to the mysterious vibe. After a long and simmering buildup, 6-string finally features more prominently, with Manzanera’s bending phrases starting around 3:42—more than halfway through the track. Yet here he still plays minimally and tastefully, displaying great maturity and patience.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)