Chicago trio Black Duck’s self-titled debut album is an absorbing collection of atmospheric, even cinematic, Midwestern-noir. The band’s three linchpin instrumentalists—guitarist Bill MacKay, guitarist/bassist Douglas McCombs, and drummer Charles Rumback—conjured the bulk of the music out of studio improvisations, played with a relaxed, nuanced flair that fans of each of these notable free-ranging musicians will recognize.

Lemon Treasure

McCombs is known as a founding member of post-rock pioneers Tortoise, as well as the leader of instrumental Americana group Brokeback. He’s also the longtime bassist for influential alt-rock outfit Eleventh Dream Day. MacKay’s ventures, meanwhile, include guest stints with McCombs’ Eleventh Dream Day and duo collaborations with the likes of banjoist Nathan Bowles, alongside a sequence of solo albums, plus two intricate instrumental LPs made with songwriter-guitarist Ryley Walker. Rumback, who met MacKay in college, also recorded two excellent instrumental discs with Walker, and has released several albums as a leader, too. Perhaps the most compelling is 2020’s standout, June Holiday (featuring extraordinary Windy City pianist Jim Baker). Improvisation has been Black Duck’s initial focus onstage, and studio improv yielded most of the tracks on the new album. But three hook-laced compositions—one brought to the session by each member of the band—serve as sonic tent poles for Black Duck. Inviting opener “Of Lit Backyards,” written by McCombs, is a loping, lyrical number that McCombs describes as “sort of Roy Orbison meets Tom Verlaine.” “Delivery,” MacKay’s growling contribution, builds to something much darker and more volatile, as if Link Wray scored a spaghetti Western shootout. Rumback’s pensive “The Trees Are Dancing” could be the most compelling of the three, with beautiful guitar melodies unspooling over a stalking bassline and clapping drums. Even though each began as a solo composition, McCombs points out that these tracks all ended up as group arrangements when realized for Black Duck.

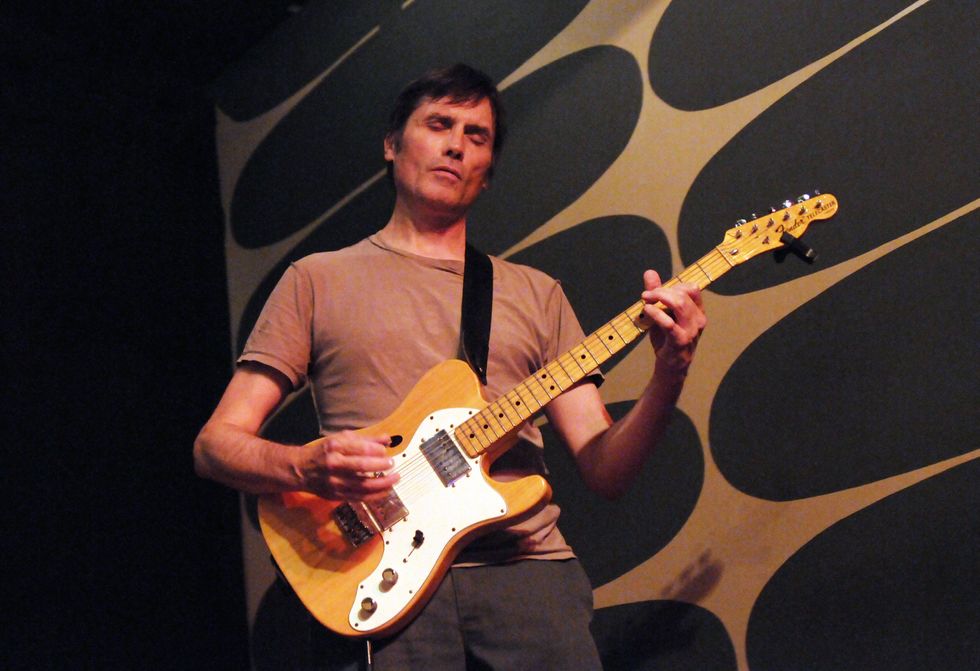

Bill MacKay's Gear

Black Duck improvises a lot of their music, but guitarist Bill MacKay says there’s usually a theme that their songs center on.

Photo by Jim Summaria

Guitars

- 1975 Fender Thinline Telecaster with Fender humbuckers

- 1976 Gibson Les Paul Custom

Amps

- 1970 Fender Princeton Reverb

Pedals

- • Wampler cata

- Pulp ThroBak Overdrive Boost

- Boss RV-3

- Death By Audio Reverberation Machine

Strings, Picks, & Slides

- Ernie Ball, mixed set of Power Slinky and Regular Slinky (.011-.046)

- Ernie Ball Power Slinky (.011-.048)

- Gibson XH Extra Heavy Standard Pick (1.17 mm)

- Dunlop Gator Grip (1.14 mm)

- Dunlop Gator Grip (1.50 mm)

- Diamond Bottlenecks Pill Bottle glass slides

McCombs, who moved to Chicago in 1980 from small-town Illinois, describes the music community of his adopted city as “having a real openness to adventure.” Black Duck, he says, is a product of its environment. “The various creative music scenes in Chicago, whether jazz and improvisation or electronic music or rock or whatever, sort of intersect in a general swirl of creativity,” he says. “When we first started performing out as a band, we played the Constellation, a progressive, European-style venue here that has a genre-less aesthetic that we all identify with. Eventually, we played the Big Ears Festival in Knoxville, where I think we fit in well as an improvising group.”

Starting out in the ’80s, McCombs was inspired by punk rock, and his band Tortoise earned its renown for studio experimentation. “Bill and Charles have more experience as live improvisers than I do,” he explains. “But the main idea behind Black Duck, for me, was to further develop my guitar playing through improvisation in a group setting, to expand myself as a musician. The three of us don’t rehearse that much or even have a whole lot of discussion, having cultivated our musical rapport on stage. We try to keep things instinctual, intuitive, open. From the first, the trio felt like it had the potential to get really expansive or be more intimate—the music seems to have a lot of pliability.” McCombs says there’s room for Black Duck to “get more ‘out,’” but the more “‘inside’” sound of Black Duck is just what happened when they went into the studio.

McCombs plays a Fender Jazzmaster on the record, as well as an Allparts Baritone Telecaster to fill out the bottom end on various tracks, such as “Delivery.” He also overdubbed bass on a few songs with his Guild B-30 acoustic bass guitar. “I’ve never been one of those players in search of the perfect guitar,” McCombs says. “I’ve always been someone who tended to adapt to my instruments. My gateway to the guitar from bass was a Fender Bass VI in the ’90s, which I played a lot in Tortoise and Brokeback. I then went to my Jazzmaster out of my love for Verlaine and his sound. The scale of it felt comfortable coming from bass, and I also love the versatility of the Jazzmaster’s pickup sounds. As for my baritone Tele, it adds more low-end to a two-guitar band. I also love the Duane Eddy twang you can get from it.”

“The various creative music scenes in Chicago, whether jazz and improvisation or electronic music or rock or whatever, sort of intersect in a general swirl of creativity.”—Douglas McCombs

MacKay, a Pittsburgh native who settled in Chicago in 1998, can play with what McCombs calls “a real rock guitar feel, that Stones-y, chooglin’ thing you can hear in ‘Delivery,’ a method that tends to be more chordal than my note-y approach. Our styles are complementary, I think.”

MacKay agrees that he and McCombs occupy different territory. “Douglas is a very different guitarist than, say, Ryley Walker,” says MacKay. “I tend to bob and weave a lot with Ryley, whereas Doug and I will play in more delineated rhythm and lead roles. Or if I’m doing a slide thing, he’ll be pulsing, as happens in ‘Lemon Treasure’ on the album. You can also get an idea of our guitar weave really well on the improv ‘Second Guess.’ We’re both fans of full-frequency guitar playing. As a bassist, too, Doug is keenly aware of the bottom even when he’s playing guitar. His baritone instrument helps with that, of course. Having some low-end emphasis in there means that the music can resonate with a listener’s body as well as their minds.”

Douglas McCombs' Gear

The three members of Black Duck say they’re experiencing an uptick in performing opportunities for improvised music recently, including Big Ears and other notable festivals.

Photo by Evan Jenkins

Guitars/Bass

- 1964 Fender Jazzmaster with Mastery bridge

- Allparts Baritone Telecaster with Fralin pickups and Bigsby tremolo

- 1970s Guild B-30 acoustic bass guitar

Pedals

- Alan Yee Last Temptation of Boost

- Fulltone Full-Drive2

- ZVEX Woolly Mammoth

- Lehle Mono Volume

- Moog Moogerfooger MF-104Z

- EarthQuaker Disaster Transport

- TC Electronic Ditto Looper

- Electro-Harmonix Freeze Sound Retainer

- Moog Moogerfooger MF-102 Ring Modulator

Amps

- 1960s Ampeg B-18N Portaflex

- Victoria Victorilux 3x10 Combo

Strings, Picks, Cables

- D'Addario EJ21 XL Jazz Light (.012-.052), with wound G string for JazzMaster

- D’Addario baritone sets

- Dunlop Orange Tortex picks

- Divine Noise guitar cables

MacKay says Black Duck sounds different than anything the three musicians might do on their own. Having three distinct perspectives bouncing around creates more possibility. “Charles and I know the mutual directions we can go down and follow each other,” says MacKay. “With Doug in the mix, it makes things more combustible.”

Black Duck’s music is spontaneous, but there’s some semblance of order to the spontaneity. “Improvisations seem most successful to me when they have something of a compositional quality,” says MacKay. “With this band, we’re not starting from complete abstraction like more jazz-oriented improv groups. One of us will have a theme or a motif we can center on. For the improvised piece ‘Thunder Fade That Earth Smells,’ I brought out a bit of a riff that I had played before, something heavy and fuzzy that could play off the more ethereal sections. I like having an unheard riff in my back pocket like that, and seeing how the other guys react to it.”

MacKay plays a “pretty stock” 1975 Fender Thinline Telecaster on Black Duck, “except that it has Fender humbuckers, which are powerful,” he explains. “It’s a dream guitar to play, with a lot of great tones beyond the usual Telecaster twang. You can get clear, clean tones, but the pickups are hot, so the Tele can be pushed into some dirty sounds. It’s a partial hollowbody, so it has some real resonance, too. It has been my main performing guitar for a long while.” MacKay also plays a ’76 Les Paul Custom that he’s had for decades. “It’s all stock, except for a new wall cord,” he says. “The Gibson is an excellent all-around instrument, as it has both warmth and bite, with so much color.”

“I’ll see an instrumentalist perform and it sparks something in me. That experience can sort of clear the connections and allow new energy to come through. To me, that’s a kind of transcendence.”—Bill MacKay

MacKay’s key effects pedals for Black Duck included a ThroBak booster (which “is based on the Colorsound Overdriver, for that vintage Jeff Beck/David Gilmour sound”), a Wampler cataPulp (“for nice distortion tones, based on the Orange Rockerverb amp”), and a Boss RV-3 reverb/delay (“which I’ve used for every show and album for more than 20 years”). As for McCombs, he summons an array of atmospheres via his board of delay, fuzz, overdrive, and looper effects, which include Alan Yee’s Last Temptation of Boost pedal (with more details in the gear list below).

The simplicity of the album cover belies the depth of creativity and improvisational transcendence in Black Duck’s recorded debut.

At 43, Rumback is the youngest of the trio, having moved from his native Kansas to Chicago in 2001. McCombs credits the drummer’s “intense knowledge of rhythm and the way his playing balances solidity with a sense of restraint” with building out Black Duck’s sound, and MacKay adds that Rumback “has his own voice on the drums.” “He totally is himself on his instrument, which is easier said than accomplished,” says MacKay. “He places beats with his phrasing in such an individual, personal way. With drums as much as guitar, phrasing is like breathing. It’s a subtle but potent aspect of music.”

Instrumental acts may never be on Top of the Pops, but MacKay takes heart in “how much instrumental music there seems to be, quiet or loud, on festival bills.

“There seems to be an openness to abstraction in music these days,” he says. “Words and the human voice have their own special expressive power, of course, but I think there’s a space in instrumental music where listeners can find themselves. I know that I’ve been in a rut sometimes, but I’ll see an instrumentalist perform and it sparks something in me. That experience can sort of clear the connections and allow new energy to come through. To me, that’s a kind of transcendence.”

YouTube It

Here, a recording of a live set at a record store in Milwaukee captures Black Duck at their most raw and powerful.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)