The Wrecking Crew was a group of Los Angeles session players who shaped hundreds of hit records in the '60s and early '70s. The list of guitarists often named as crew members includes Tommy Tedesco, James Burton, Glen Campbell, Al Casey, Barney Kessel, and Howard Roberts. More rarely mentioned is Don Peake, who was right there in the studio trenches with them, creating timeless tracks for Phil Spector and others.

Peake later cut hits for Motown as well. If you listen to classic pop radio, you have doubtless heard the iconic opening wah-wah lick to Marvin Gaye's "Let's Get It On" and the guitar line doubling the bass on the Jackson 5's "I Want You Back," but probably never knew it was Peake playing those parts.

Though he appears briefly in The Wrecking Crew movie, it's safe to say Don Peake's place in the world of historic session guitarists is shamefully unsung. It's long past time for this purveyor of iconic guitar parts to be recognized. While many of his peers have departed, Peake luckily remains with us, ready to relay some amazing stories, which he does in this Premier Guitar interview.

"Elvis would come in three nights a week. We'd sit with him in the balcony on the break." —Don Peake

Don Peake was born in Los Angeles, California, on June 7, 1940. During high school, he played clarinet and sang with an a cappella choir. Picking up the ukulele at 16, he eventually moved to guitar. When word got out he could play Gene Vincent's "Be-Bop-A-Lula," it was recommended he try out for a gig with rockabilly singer Jackie Lee Cochran.

"I went to a night club called the Rag Doll," Peake recalls. "In the parking lot was a line of guitarists waiting to audition." Cochran fortuitously asked Peake if he knew "Be-Bop-A-Lula," and an affirmative answer helped him clinch the gig. Opening night, after playing that song, Cochran asked the young guitarist what else he knew. "Nothing," he replied.

Peake managed to keep the job, but to fill in the gaps he quickly signed up for lessons at Clara Joyce Sherman's School of Music in Hollywood. As luck would have it, his guitar teacher was Ray Pohlman, who would go on to be a regular guitarist and bassist in the Wrecking Crew. "Ray was a jazz guitarist who played with the Billy May Orchestra," he says. "He taught me to play and mentored me. I bought my blonde, 1946 Gibson ES-350 with the single pickup from him." A special guitar, indeed: The ES-350 Peake bought from Pohlman was a rare one-pickup jazz model made in 1946. Gibson started making the iconic two-pickup models in 1947.

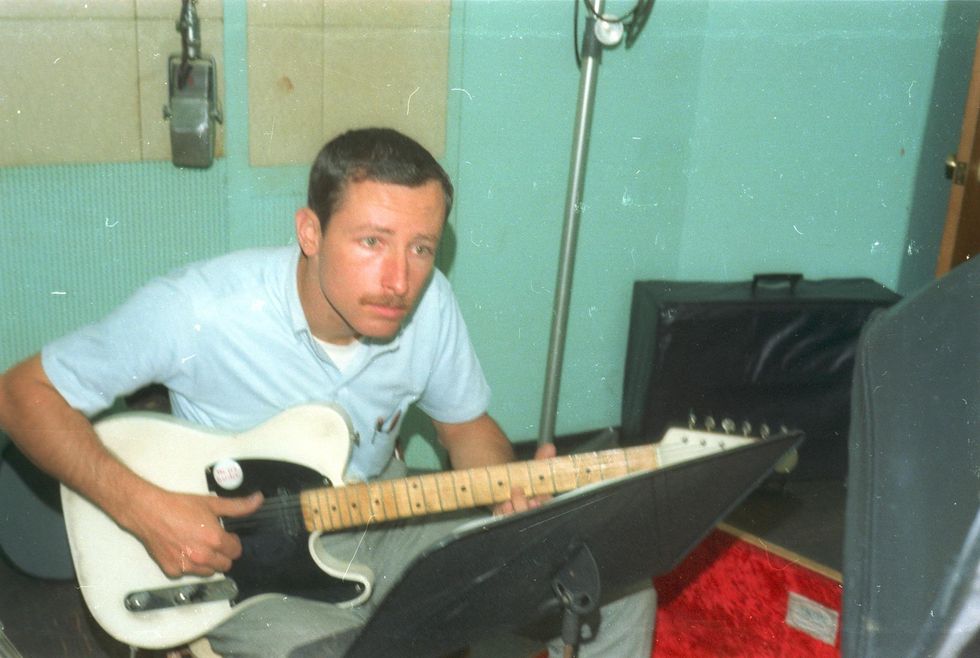

Here's Peake at work in studio, putting his skill at reading music to work. This is a still from the documentary film The Wrecking Crew.

Working with Cochran helped cement the young guitarist's reputation as a rock 'n' roll player, which led to a gig with Lance LeGault, Elvis Presley's movie stand-in. "LeGault loved Ray Charles' songs and had his sax player write out 'Hallelujah, I Love Her So,' 'Drown in My Own Tears,' etc.," says Peake. "I learned the exact guitar parts, which came in handy later. Elvis would come in three nights a week. We'd sit with him in the balcony on the break."

Learning to read music while playing rock 'n' roll gigs provided Peake a perfect primer for later working with the similarly schooled Wrecking Crew, who also helped create much of the era's teenage music. Another bit of serendipity was hanging out with a young Phil Spector.

"Phil was studying with Howard Roberts," Peake remembers. "I started studying with both Barney Kessel and Roberts. Howard would write out arpeggios for me, while Barney was 'Mr. Time.' He would say, 'You've got a rod connecting your forearm to your foot. You have to tap your foot and keep your arm moving. It doesn't matter if you miss the chord, keep going. Never stop your right hand.'" Spector gave Peake a T-Bone Walker LP, adding a blues influence to the guitarist's jazz and rock background. "T-Bone had those wonderful moving 9th chords," he says.

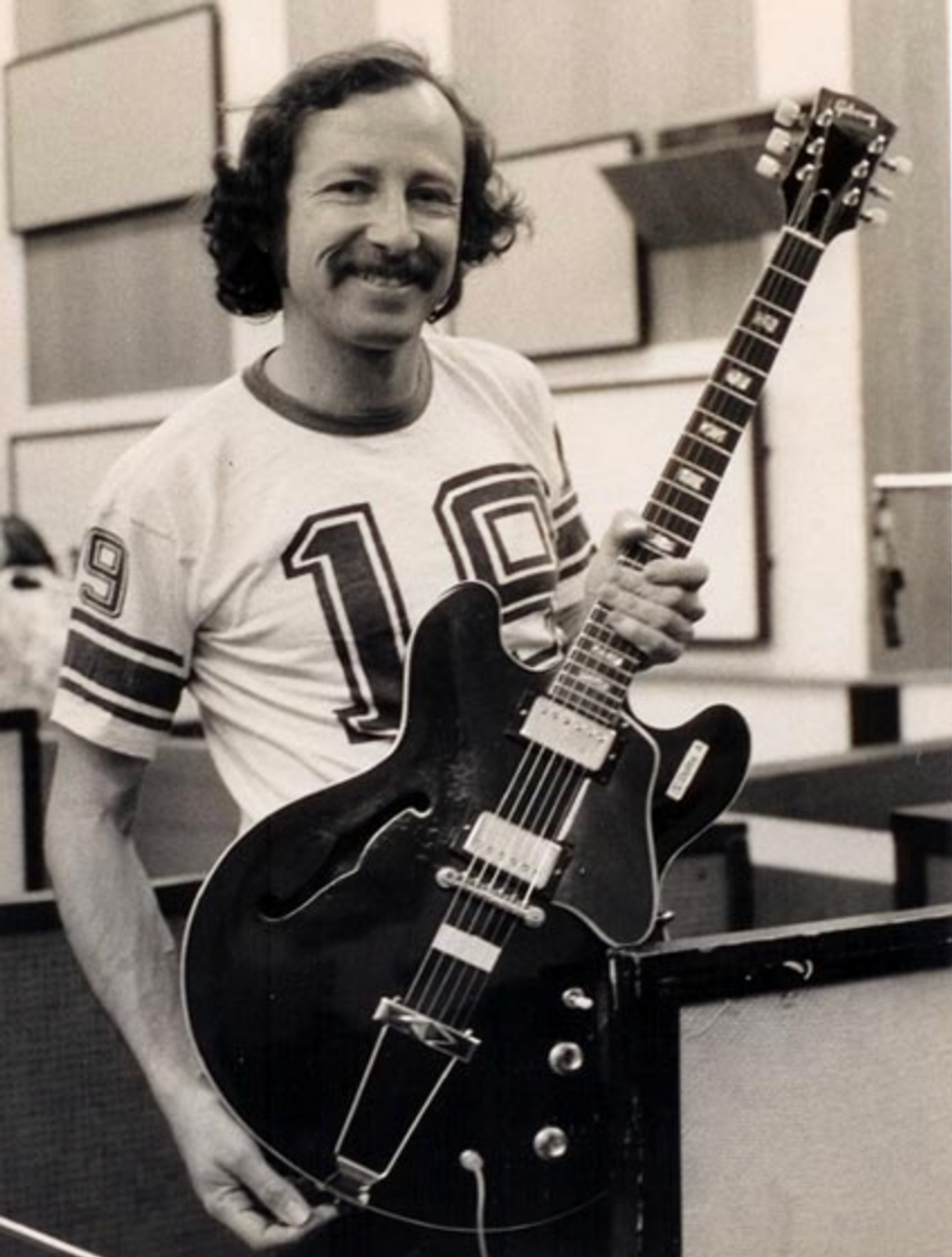

Shown here in 1972 at an RCA Hollywood Studio session, Peake holds a modified ES-335 that began life as a 12-string, owned by John Phillips of the Mamas & the Papas. Fellow sessioner Paul Herman got it from Phillips and cut down the headstock and painted it black before selling it to Peake, who then used the instrument as his primary studio axe.

Courtesy of Don Peake

Spector's friend Marshall Leib, from his group the Teddy Bears, told Peake that the Everly Brothers were looking for a guitar player. Playing with the Everlys would be his first big gig and place him at the center of the musical revolution taking place in early '60s England.

"We flew to London," he recalls. "After the gig, we went to a night club where a pretty good band was playing." Still wearing their matching gray suits, it was clear that Peake and company were a band as well, so the local performers joined them on their break. Among those locals were Albert Lee and Eric Clapton. In his autobiography, Clapton describes Peake as one of the American guitarists who impressed him as being technically better than he was.

On the next trip to England, the Everly Brothers headlined a tour featuring the Rolling Stones, Bo Diddley, and Little Richard. "As I was watching one of the other acts, I noticed a black man in a full-length peignoir across the stage, holding a bible," he says. "One of the stagehands said, 'That's Little Richard Penniman.'"

"Brother Ray came in and sat down at the piano. He said, 'Do you know 'Hallelujah, I Love Her So?'—cut back to Lance LeGault, making me learn those Ray Charles songs—I said, 'Absolutely.'" —Don Peake

Brothers and band soon started hanging with the Beatles and Stones in Hamburg. "The Star-Club had three stages," says Peake. "We traded sets: Everly Brothers, Rolling Stones, Beatles. Jim Gordon came over as the drummer. He went on to play with Clapton."

During his Everly Brothers tenure, Peake had to leave his 1951 Fender Broadcaster at home. "The Everly Brothers were sponsored by Gibson, so we weren't allowed to use a Fender guitar onstage," he explains. "They gave me a brand new, bright red SG. We were strumming hard, and it would constantly break the 3rd or 4th string. I didn't have a spare guitar, so I would finish the show playing an octave higher."

Once back in Los Angeles, producer Jimmie Haskell heard about Peake and arranged for him to play with Ricky Nelson. "I played on the Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet sessions for a little while," he says. "James Burton was there at the same time. He came in the studio one day and started bending strings. I said, 'How did you do that?' He said, 'I've got an E string, where my G string is supposed to be.' That was the first time we saw anybody play a light G string."

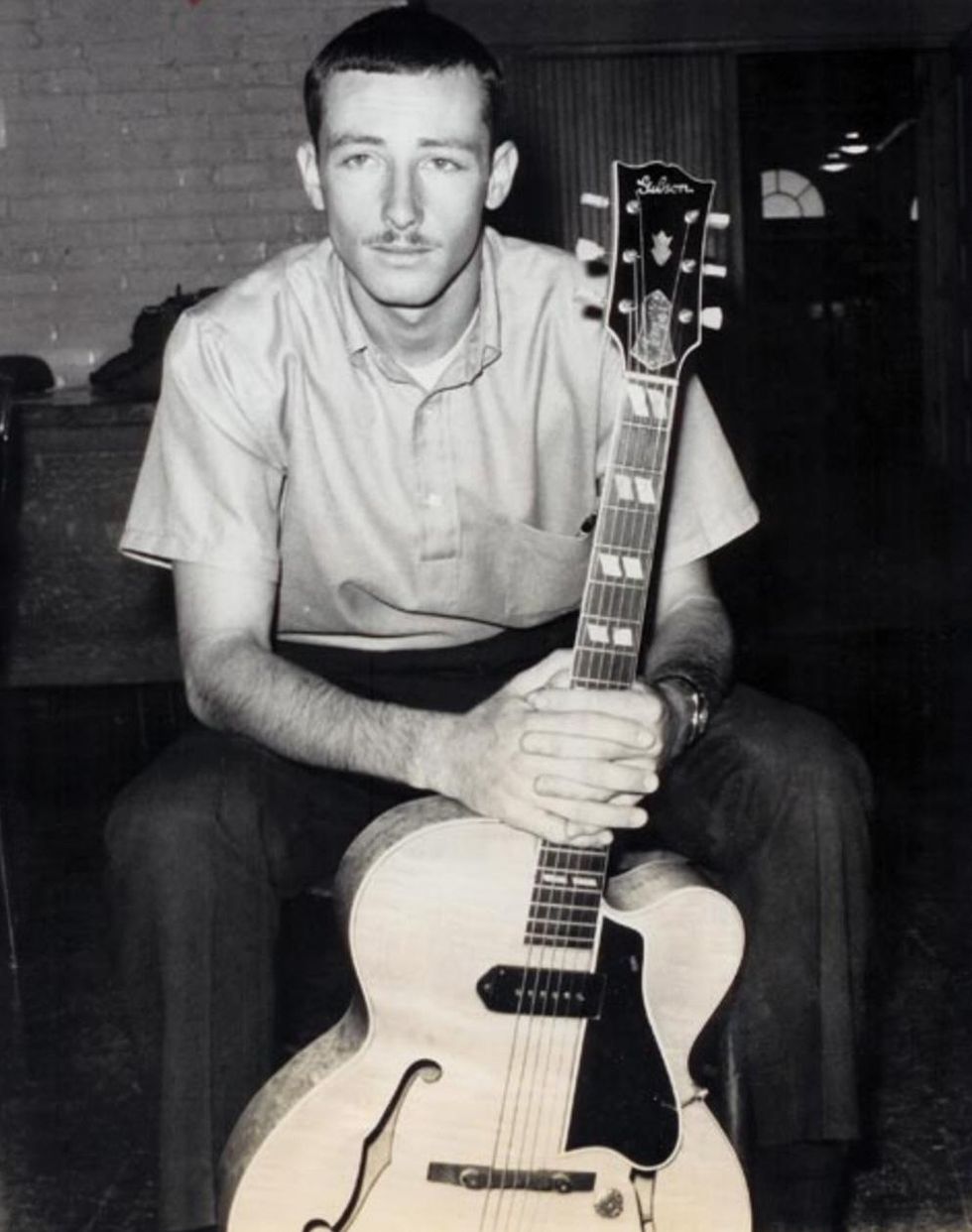

Don Peake bought this blonde 1946 Gibson ES-350 with a single pickup from Ray Pohlman, his guitar mentor and Wrecking Crew bandmate. This rare jazz model was a precursor to the two-pickup model introduced in 1947. Peake's chart-reading and big-band chops were honed while playing in the jazz band at L.A. City College, where this photo was taken in 1960.

Photo courtesy of Don Peake

Peake's sessions with the Wrecking Crew started around 1966 with the Righteous Brothers' "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'." That record would define Spector's "Wall of Sound" and become one of the most played radio tunes of all time. A sizable chunk of that "wall" was the guitar section, including Barney Kessel, Howard Roberts, Bill Pittman, Tommy Tedesco, and Peake, all playing together.

"Tommy or Barney would be the first chair," Peake recalls. "There were always three guys playing miked Gibson L-5s. I bought mine from Howard Roberts. The board at Gold Star only had seven channels, so they had all the guitar mics running together on one channel. Phil would have us move around to get the balance. He would rehearse us for three hours. Howard Roberts once said, 'Man, you come out here and play this. I'm getting tired.'"

Peake is featured on another major hit that sounds like a Spector production, but isn't. "One day, I'm up at Armin Steiner's studio and a shaggy-haired guy comes in with a beautiful girl in bangs," he relates. "The producer said, 'This is Caesar and Cleo.' The song was 'Baby Don't Go.' I did the tremolo strumming part."

"Don was the best reader of the three of us and would help us with any problems reading charts." —Louie Shelton

A week later, Ahmet Ertegun heard the duo, changed their name to Sonny and Cher, and ordered a full album, which included the massive hit "I Got You Babe."

"That tune is me on my Fender Telecaster with a lot of reverb," says Peake. "Sonny produced the records. He'd been a gofer for Phil Spector and, like Phil, he was into lots of reverb and long rehearsals. Barney Kessel was sitting next to me. He had played jazz with Charlie Parker and Lady Day [Billie Holiday]. After playing this one F7 chord for three hours he said, 'Sonny, if a doctor told me I had only two weeks to live, I'd spend them with you because each moment is like an eternity'."

In 1964, Peake landed a gig with a man whose music had inspired him as a teenager. While recording at Gold Star Studios, he ran into his friend Arthur Wright on the phone with Ray Charles' manager Joe Adams. Wright put Peake on the call.

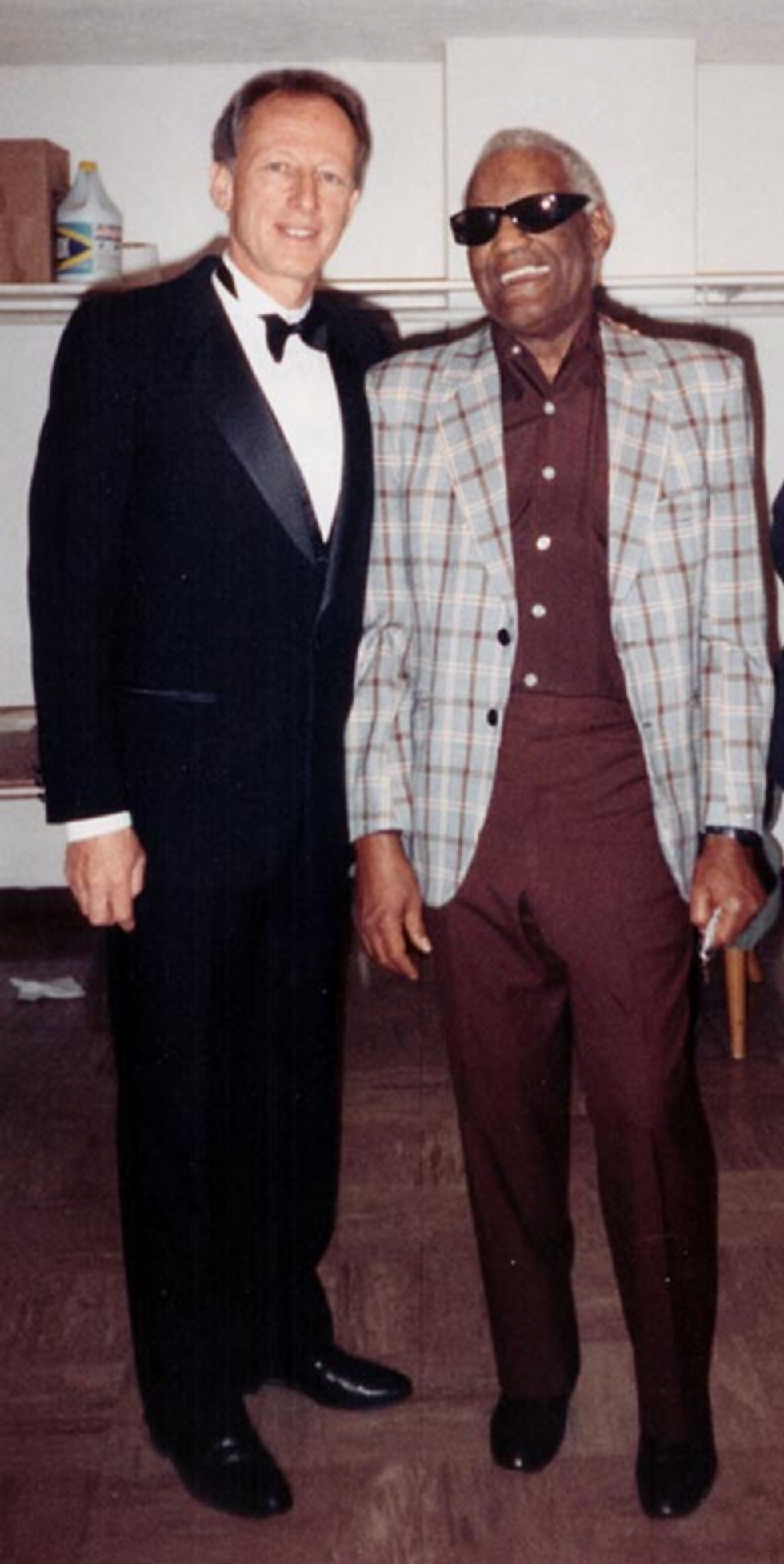

Don Peake with his boss, the great Ray Charles, in the dressing room before a show in Wichita, Kansas, circa 1993.

Courtesy of Don Peake

"Adams said, 'Ray Charles is looking for a guitar player," he recalls. "We've tried 35 guys and can't find anybody who can play the blues, read music, play jazz, and already knows Ray's old songs, because we've lost some of that music.' I said, 'I'm white.' He said, 'Can you play?' I said, 'Yes.' He said, 'Get down here.'"

Peake grabbed his Deluxe Reverb, Gibson L-5, and ES-350, and drove to the studio, where he hauled all three up a flight of stairs. With his hands full, he kicked open the rehearsal room door, slamming it into the wall.

"Staring at me were five saxophones, four trombones, four trumpets, bass, drums, an empty piano chair, and an empty guitar chair," he says. "I'd been playing with the jazz band at L.A. City College, so I knew how to read big band charts. The drummer called an up-tempo Count Basie blues and I started playing that L-5 as fast as I could. Leroy Cooper, the baritone player, leaned over to Lily Fort, the lead singer of the Raelettes, and said, 'That boy is serious.' Then they said, 'Get out your electric.' I picked up the 350 and we did 'Jumping with Symphony Sid.' Brother Ray came in and sat down at the piano. He said, 'Do you know 'Hallelujah, I Love Her So?'—cut back to Lance LeGault, making me learn those Ray Charles songs—I said, 'Absolutely.'"

Joe Adams informed Peake that Charles wanted to hire him at $200 a week. "I told him the Everly Brothers were paying $225," says Peake. Adams said he would have to talk to Mr. Charles. Fearing he had blown the gig of a lifetime, Peake drove to his mother's house, where he lived when he was off the road. "She said, 'Joe Adams called," he recalls. "They're going to pay you $225, but give you a separate envelope for the $25, so the rest of the band doesn't know about it.'" Thus, Don Peake became the first white guitarist to play with Ray Charles.

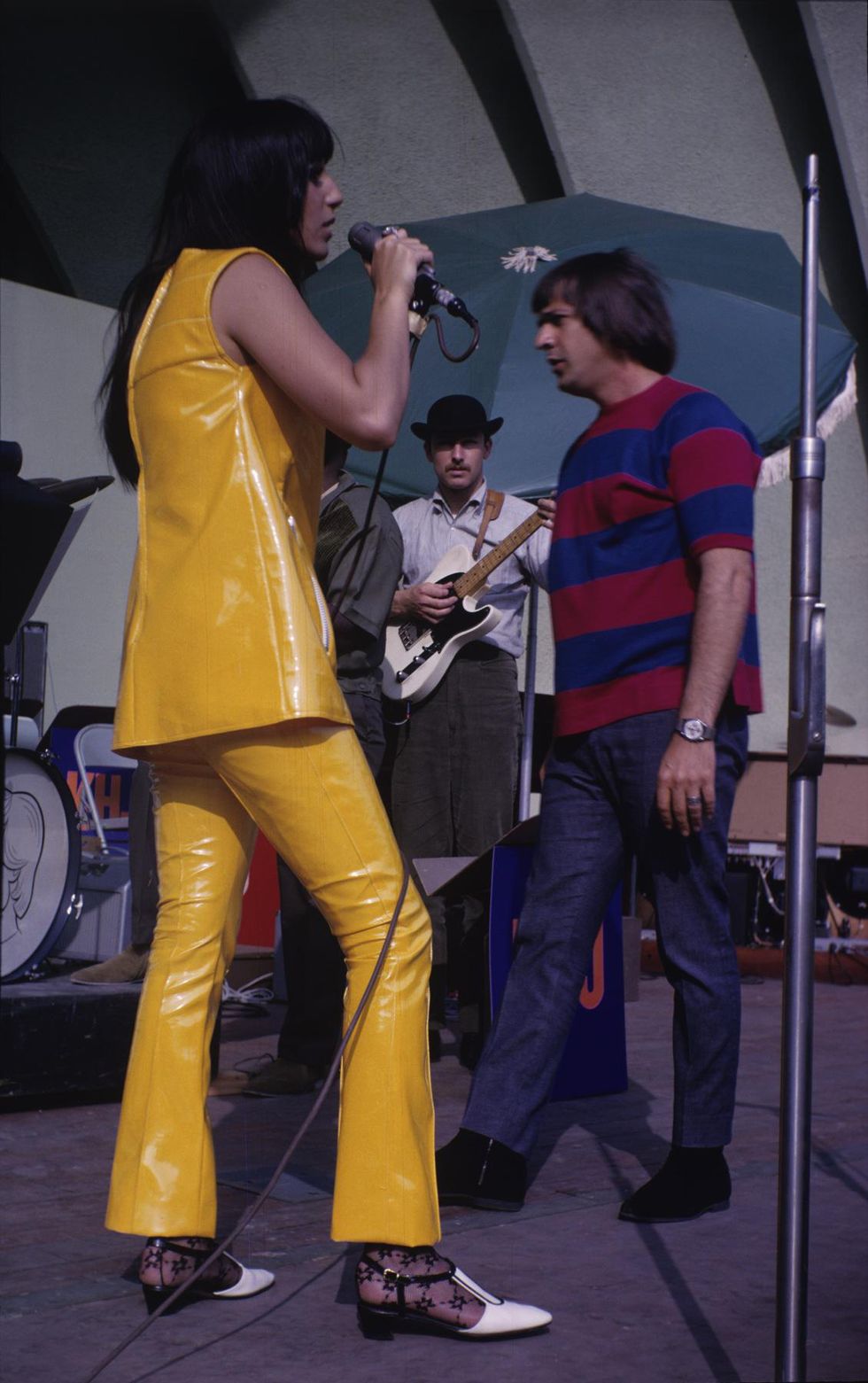

Don Peake peeks out of a Sonny and Cher sandwich while backing up the iconic duo at L.A.'s Hollywood Bowl in 1966.

Courtesy of Don Peake

Before they hit the road, Charles recorded a live album. During the show, he began playing the introduction to "Makin' Whoopee"—a song for which there was no chart. "I had never played it with him," says Peake. "When he goes up a half-step on the dominant you can hear me slide into it. I'm learning the song onstage while they're recording it."

Peake continued recording with Charles even after he stopped touring with him, cutting classics like "America the Beautiful" and "Crying Time." He can be heard loud and clear on a lesser-known Charles cover, "Blue Moon of Kentucky," playing the signature intro and the solo over the fade. Toward the end of the track, you hear Charles exhorting the guitarist, "Play it! Play it 'til it gets good." Rather than being critical, according to Peake, he is encouraging him. "He's saying, 'Keep going. It's good,'" Peake says.

While "Blue Moon of Kentucky" is a deep cut, the guitarist's soulful blues licks on the massive Charles hit "Let's Go Get Stoned" have been heard by countless millions through the decades. Though the tone sounds Fender-ish, the guitar was an old Gibson ES-175. "I restrung it with real light strings," Peake explains. "I ended up not liking it, but I did use it on that recording."

In 1966, Peake was asked to go on the road with Bobby Darin, but told Darin he wanted to stay in town and be an arranger. A week went by before he got the call from the singer's managers. "I went to their office, where they played me 'If I Were a Carpenter' by Tim Hardin," he says. "They wanted strings and I'd never written for strings before. I went home, opened up the Russell Garcia arranging book [The Professional Arranger Composer], and feverishly figured out how to write the string quartet. When we recorded at Gold Star, I stood near the studio door so I could get out quickly. When the strings came in, I thought, 'That sounds all right,' and started walking back into the studio." This Bobby Darin hit would mark the beginning of an arranging and scoring career that would ultimately replace Peake's session work, but the guitarist still had some classics to cut.

"There are certain guitar licks or solos that always give me goose bumps, and Don Peake's opening part on 'Let's Get It On' is one of those." —Denny Tedesco

By 1969, Motown had started recording in Los Angeles. Diana Ross was going to produce the first Jackson 5 record with Ben Barrett as contractor. For the Ross-produced record, Barrett put together a band that included Peake, David T. Walker, and Louie Shelton on guitar, Wilton Felder on bass, and Gene Pello on drums. "On 'I Want You Back,' I doubled the bass line with Wilton," he recalls. "I had to read it."

Peake was quite good at that, Louie Shelton recalls. "Don was the best reader of the three of us and would help us with any problems reading charts," Shelton says.

In addition to doubling one of the most famous bass parts of all time, Peake appears on much of the Jackson's subsequent output. That's his Coral electric sitar on "Maybe Tomorrow" from Third Album and his early fuzz pedal shaping the memorable distorted part on "ABC." "I also had a Cry Baby wah," says Peake. "It said Thomas Organ Company, Sepulveda, California, on the bottom." He doesn't remember if it was him or Wah Wah Watson, aka Melvin Ragin, playing the wah part on the Jacksons' "Never Can Say Goodbye," but he is very clear about who played the memorable intro to Marvin Gaye's "Let's Get It On." As with many Peake performances, there's a fascinating backstory.

"There was a fabulous guitarist named René Hall who was also a great arranger," he relates. "Hall started using me because of my blues playing. He actually had me come in and finish a B.B. King album. B.B. had walked away from the record company and wouldn't talk to them. They had already recorded the songs but needed guitar fills, so I did them."

Peake stands beside bassist Wilton Felder on an early Jackson 5 session. Peake played essential parts on some of the group's early, barnstorming hits.

Courtesy of Don Peake

In 1973, Hall was the arranger on "Let's Get It On," working at Motown's L.A. studio on Romaine Street. "René said, 'I want you to make up something at the beginning'," says Peake. "I turned on my wah-wah pedal and played." As was so often the case in those days, Peake's name was left off the album. Wah Wah Watson was on the road with Gaye at the time, so everyone assumed he played the part. "It's me," says Peake. "I made a terrible mistake about 15 seconds in," he says. "I got excited and hit the open G string." (Editor's note: Actually, it's 13 seconds in, and you can hear it clearly.)

"There are certain guitar licks or solos that always give me goose bumps and Don Peake's opening part on 'Let's Get It On' is one of those," says Denny Tedesco, director of The Wrecking Crew movie and son of Tommy Tedesco.

In addition to playing on some of the biggest hits of the day, Peake played on numerous movie scores. Though his excellent reading skills no doubt played a part, sometimes it was his rock 'n' roll heart that landed him the job.

"I played for Elmer Bernstein on the Steve McQueen movie Baby the Rain Must Fall," he says. "Bernstein called me because, though Tommy Tedesco could pretend to be musically ignorant, I just naturally came up with stuff that was unsophisticated. Bernstein said, 'Just do whatever you want.' On the soundtrack, you'll hear me playing all this crazy guitar."

As the 1970s progressed, with guitarists like Larry Carlton, Jay Graydon, and Steve Lukather coming up, sessions began drying up for Peake's generation of musicians. The guitarist looked toward composing and arranging for the next chapter of his musical life, but to be successful he found he had to fully commit. He began studying arranging and composing with Albert Harris, a famed Hollywood orchestrator, and called composer/conductor and frequent session contractor Ben Barrett to bow out of his studio guitarist role. "He didn't say the words, 'Are you out of your fucking mind?'—but I know he was thinking it," says Peake. Sane and serious, he sold the instruments in his cartage trunk and devoted himself to a career that would provide compositions and arrangements for more than 50 movies and television shows, including Knight Rider and My Two Dads.

For the last decade, Peake has been a professor at Los Angeles' Bridges Academy, a school for gifted children that have learning differences, such as autism and ADHD. "I teach guitar, jazz, and blues," he says. "Our music program allows these children to put both sides of their brain together. They get better at their studies."

As of this writing, Peake is still playing with some of the surviving members of the Wrecking Crew, including Chuck Berghofer, the bassist who played the slithery part on Nancy Sinatra's "These Boots Are Made for Walking."

"Don Randi is playing piano," he says. "The drummer is Ed Green. We do a Glen Campbell tribute, because we played on his records. We also do a Sonny and Cher song. We were just about to go on the road, when COVID hit."

This just scratches the surface of Peake's extraordinary life. Did we mention he was a champion race car driver? While there may be no official designation of who was in the Wrecking Crew, by any definition, Don Peake deserves mention as a member of that historic assembly. Maybe even more important is the mark his guitar playing left on memorable Motown tunes that have become embedded not just in music history, but in the culture at large.

Don Peake Essential Listening:

Description: Don Peake recorded tracks with Ray Charles even after he stopped touring with the pianist, cutting classics like "America the Beautiful" and "Crying Time." Peake can be heard loud and clear on a lesser-known Charles cover, "Blue Moon of Kentucky," playing the signature intro and the solo over the fade. Toward the end of the track, you hear Charles saying to Peake with enthusiasm, "Play it! Play it 'til it gets good."

Description: Peake played the guitar line doubling the bass on the Jackson 5's "I Want You Back." In addition to complementing one of the most famous bass parts of all time, Peake appears on much of the Jackson 5's subsequent output. He plays a Coral electric sitar on "Maybe Tomorrow" from 1970's Third Album, and that's also Peake's early fuzz pedal shaping the memorable distorted part on "ABC" from the same year.

Description: In 1966, Peake was asked to go on the road with Bobby Darin, but declined because he wanted to stay put and be an arranger. A week later, Peake got a call from the singer's managers to arrange strings for "If I Were a Carpenter." Peake had never written parts for strings before, but quickly figured out how to write for a string quartet. This Bobby Darin hit would mark the beginning of an arranging and scoring career that would ultimately replace Peake's session work.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.