Just in case this whole hotshot axe-man thing didn't pan out, Gary Clark Jr. had a backup plan—more than a few of them, in fact. “My mother used to say to me, 'What if you can't be a guitarist? What then?' So I told her, 'If the guitar doesn't work out, then I'll play drums. If that doesn't work, I'll play bass. If that doesn't work, I'll play keys. And if that doesn't work, I'll play trumpet.' Or whatever. The backup plan was always music. There was never any two ways about it."

The funny thing is, Clark made good on most of his promises. While he doesn't play trumpet on his musically diverse and compelling new album, The Story of Sonny Boy Slim, the 31-year-old singer-guitar star gives pretty much everything else a go, functioning as a veritable (and astonishingly versatile) one-man band, tackling drums, keyboards, bass, finger snaps … oh, and, of course, the guitar. The album brims with the kind of fiery, emotive, and imaginative 6-string work that has prompted some writers to compare Clark to Jimi Hendrix and Stevie Ray Vaughan. But the Austin native is anything but a strict traditionalist, and on the new set he weaves psychedelic and Delta blues, chillaxed retro-soul, acoustic gospel, and gonzo garage rock into a personal sonic tapestry that's as daringly au courant as it is classic.

“I love playing guitar, but I get a lot of satisfaction from playing other instruments, too," Clark says. “My sister started playing drums when I played guitar. She kind of lost interest, so there was this nice shiny drum kit waiting for me. I just sat down and figured it out. We had keyboards in the house, so I started playing them, too. I wanted to record my own demos, and little by little, just by doing gigs, I acquired enough gear to get things going. Nobody showed me how to record—I figured it out by myself."

Clark put his self-taught production chops to the test on The Story of Sonny Boy Slim. Whereas his 2012 major-label debut, Blak and Blu, was a Los Angeles-based, three-way co-production between himself, Rob Cavallo, and Mike Elizondo, for the follow-up the guitarist set up shop at Austin's Arlyn Studios with a trio of engineers, Bharath “Cheex" Ramanath, Jacob Sciba, and Joseph Holguin.

“It's a whole different vibe making a record on your own than working with producers," Clark notes. “The guys in the studio would sometimes say, 'No, dude, that wasn't good enough' or 'That was cool. That's the take.' We did have those conversations. But I do think working on my own changes the way I play a bit. I feel more free—I feel open, like I'm at home. If I can feel completely comfortable, like I can take my shoes off, that's when I work the best."

Clark will soon open a string of arena dates for the Foo Fighters, and then he'll be supporting The Story of Sonny Boy Slim with a headline run that currently stretches into April 2016. Before hitting the road, he sat down with Premier Guitar to dissect his playing on the new album and trace the evolution of his early years woodshedding with his friend Eve Monsees. He also discussed his beloved Epiphone Casinos and Fender Vibro-Kings, along with other guitars and gear, while positing the notion that he “wasn't born in the right decade."

It's widely thought that blues players don't spend a lot of time practicing technique or studying theory—it's all feel. What are your practice habits?

Well, yeah, I could study up on that more. I don't practice as much as I could, to be honest. When I'm up onstage playing and I hit a bum note—you know, it happens—I'll think to myself, “You see? You've got to practice a bit more before you get up in front of all these people." It's a struggle sometimes. No matter how much practice you get in, you could always do more.

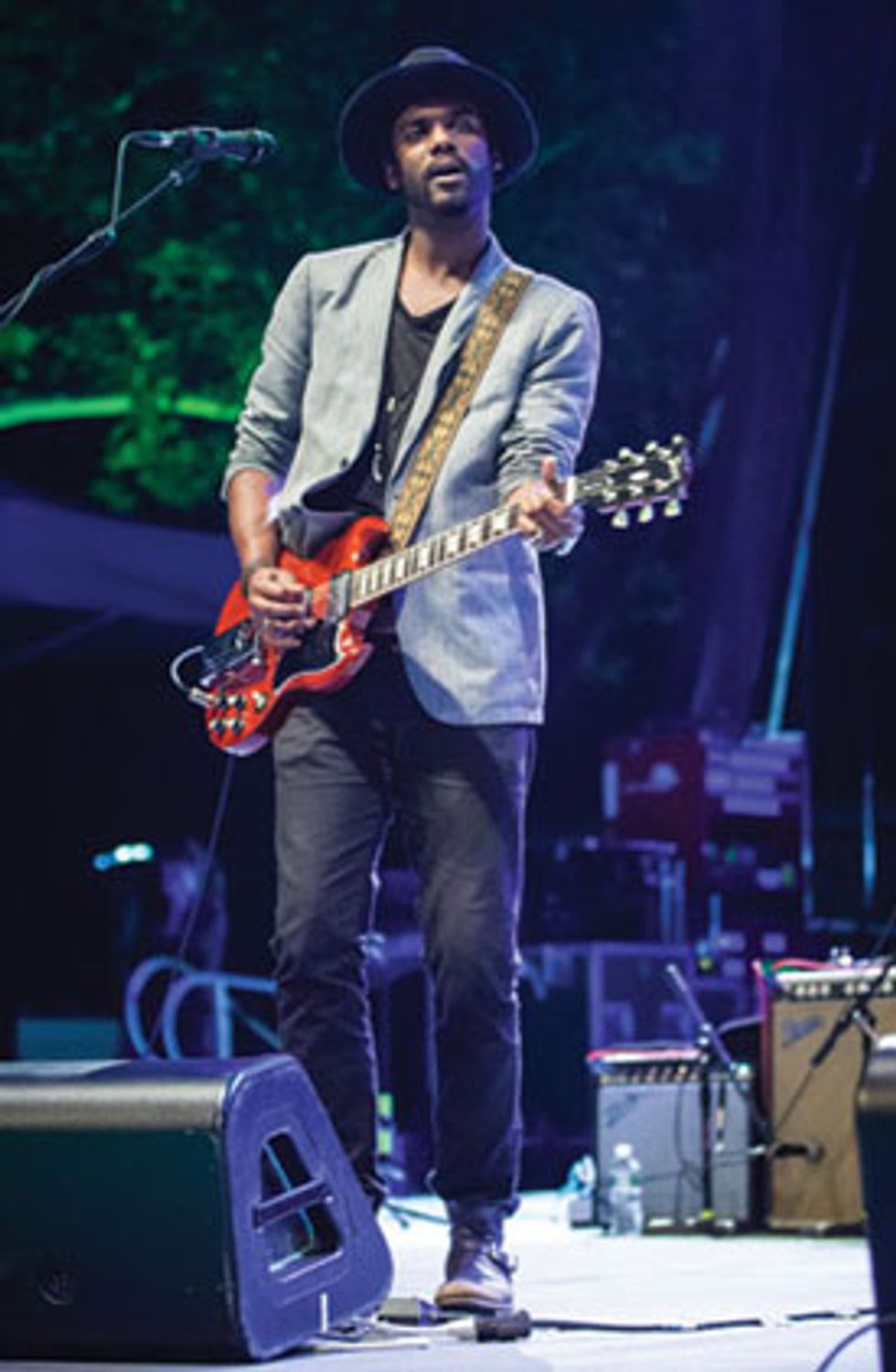

Gary Clark Jr. says he's a man of symmetry when it comes to guitars. No single-cutaways for this slinger, but an SG makes the grade. Photo by Joe Russo

Is it true that your first guitar was an Ibanez RX20 you got after seeing Michael Jackson?

That's right. That was great.

Did you want to be a shredder like Jennifer Batten, who was playing with him at the time?

I did, I did. But as soon as I got my guitar and I couldn't play the solo to “Beat It," I thought, “That's it. I might just need to move on to something else." [Laughs.] Sure, I wanted to be a shredder after I saw that concert, but I also loved clean, soul guitar tones. I remember when I asked my parents for a guitar, I said, “You know, so I can get that muted kind of sound." I wanted a “mute guitar"—I didn't know what things were called. I didn't understand what a hollowbody was or a semi-hollow or a 335 or anything like that. I just wanted to do cool, soulful hammer-ons, things like that.

When you were a kid, you formed an incredible friendship with a girl named Eve Monsees. You two would spend hours in her garage playing the guitar. What kind of things did you jam on?

We would jam on 12-bar blues, basically. We would go back and forth between major and minor keys. We thought we were really advanced for our age. [Laughs.] We were into Jimmy Reed and guys like that. And there'd be rock 'n' roll stuff—the Ramones. But most of the time, it was just us hanging around and playing pentatonic stuff, learning how to play solos over 12-bar blues.

I remember Eve was into listening to these two stations on the radio—91.7 and 90.5. One deejay, Larry Monroe, hosted a blues hour. That's how we discovered guys like T-Bone Walker and Albert Collins, Jimmy Reed, and Muddy Waters. Larry really educated us. If I missed a show, Eve would record it off the radio and give me a tape. “You didn't hear this. Check it out." I was so into it.

Then I started going to blues jams. I met these older guys who would sort of school me about where the music came from. My first blues album was Stevie Ray Vaughan's Texas Flood—my neighbor Fred Wheeler gave it to me. After hearing Stevie Ray, I was like, “Oh, shit. What is this?" It was eye-opening. From there, I started learning about Albert King, and I just kind of went backwards.

“I like to turn the volume down and really get that thin clean tone," says Clark about Strats. “And then for solos I'll crank it up and let the bridge pickup wail a little bit." Photo by Debi Del Grande

Eddie Van Halen has talked about learning Cream's version of “Spoonful" note for note. Did you ever do stuff like that?

I did, sure. I went straight for Hendrix and “Purple Haze," and Stevie Ray's version of “Little Wing." Those are the ones that I tried to get note for note. All I would think about at school was, “Man, I can't wait to get home and figure out that second verse."

Is that how you learned to build a solo?

A lot of it was watching and listening. I have to give it up to guitarists like Alan Haynes, Derek O'Brien, Johnny Moeller, and Mike Keller. Those are the guys in Austin I would see here and there. Just their improvisation and how dynamic they would be—you give them 24 bars or a 36-bar solo and just listen to them build. You go from “Oh, that was really cool" to “Wow, my mind was just blown by this." Those are the guys I listened to and tried to figure out what they were doing.

In Austin you got to jam with guitarists like Jimmie Vaughan and Hubert Sumlin. Were you watching their fingers as they played?

Oh, I was definitely watching their fingers. They have their own identity when they pick up a guitar. You close your eyes and listen, and you go, “That's Jimmie Vaughan. That's Hubert Sumlin. That's Buddy Guy right there." It made me think. Instead of trying to play Freddie King note for note or whatever, I could make it my own and figure out what works for me. What's the best way to play the instrument to my ability? I really got that just from being with them, because that's what they were doing.

How did that affect your picking style? Are you a hard or soft picker?

Well, they weren't using picks at the time. I would see Jimmie Vaughan, and he was all fingers. Hubert Sumlin was all fingers. So I was playing with these guys who didn't use picks. I liked the way they would get this nasally tone with their fingers. I was really into that for a while, but then I also realized I was better off with a pick. I would say I'm now somewhat of an obnoxiously hard picker. [Laughs.] No finesse about it. I'm pretty ruthless when it comes to playing with a pick.

You mentioned Hendrix and Stevie Ray—both were big Strat players. I know you use a Strat sometimes, mostly for songs that are more soul and R&B.

Yeah, definitely. For that kind of stuff I really like the Strat. I like to turn the volume down and really get that thin clean tone, and then for solos I'll crank it up and let the bridge pickup wail a little bit. I play near the bridge and get that twangy, nasal sound.

The Casino has been your main guitar. What was it about the Casino that first appealed to you?

I could finally get that B.B. King tone I was looking for. I love his sound and T-Bone Walker's sound. I was really into those guys at the time I picked up the Casino. It was just a different sound that I couldn't really get out of a Strat. I also liked that I could play it acoustically and still get a lot of sound out of it without plugging in. You can play a Casino anywhere, and it gives you something back.

Gary Clark Jr.'s Gear

Guitars

Epiphone Casino (red with Bigsby)

Epiphone Gary Clark Jr. Blak & Blu Casino (prototype)

Epiphone Casino (burled red, bought in the U.K.)

1961 Gibson Les Paul/SG Standard (gift from the Foo Fighters' Pat Smear)

Gibson ES-330

Gibson ES-125

2000 Fender Stratocaster

1970s Fender Telecaster

Fano JM6

Amps

Fender Vibro-King 20th Anniversary Edition combo

Fender Vibro-King head with matching 2x12 cabinet

Fender Princeton

Effects

Fulltone Octafuzz

Hermida Audio Zendrive

TC Electronic PolyTune

Strymon Flint Tremolo & Reverb

Dunlop GCB95 Cry Baby Wah

Fulltone A/B box (runs two amps)

Strings and Picks

D'Addario Custom Nickel .011–.049 (lower-tuned guitars use .011–.052)

Dunlop Poly Medium picks

Did single-cut guitars like Les Pauls ever appeal to you?

No, honestly. Visually, they just didn't look right to me. They look great on some guys, but not on me. Aesthetically, I like things to be even. I have this weird thing where if it's a little bit off, it makes me uncomfortable. That's just me—the way my mind works.

As a teenager, how did you start to educate yourself about different combinations of amps and effects?

That really comes from hanging out with [Eric “King"] Zapata [rhythm guitarist in Clark's band]. I have to give it up to him on tone and putting the combos together. He sold me my first tube amp, my Fender Vibro-King. I'd show up to play with guys like Alan Haynes, and I'd have my solid-state Crate amp. No disrespect to Crate, but I'd always look back to my amp and think, “How come mine doesn't sound like his Vibro-King or his Super?" I just didn't know. Zapata was the one who really helped me with the amps and combos. I tried Marshalls, but that wasn't the tone I was going for. I liked the Fenders.

You play an Epiphone Riviera at home but not live. For you, what are the sonic and playability differences between a Riviera and a Casino?

To me, the Riviera, for lack of a better word, has more of a shimmery tone to it. It sounds more like water and raindrops to me. The Casino is a little bit rounder, bolder, and then it gets all gnarly and screaming when you push it back to the bridge pickup. I like both of them for different reasons. I would play the Riviera a lot more, but it's heavy, man. It's not a light guitar.

What about your '61 Gibson Les Paul/SG Standard? Are you using that on the new album?

Oh, yeah. That's got the humbuckers. I use that guitar when I want lots of attitude. It's an aggressive guitar. It's on “The Healing" and “Grinder."

Walk me through that piercing, stinging solo sound on “The Healing." It's sort of a classic SRV sound with a little added Gary bite.

I used the SG on that, and I put it through a Vibro-King head, out to the cabinets. Everything—bass, mid, treble—everything right at the middle on 5. There's a little bit of reverb, a Strymon on the '60s reverb setting, and a little bit of delay. There's some Octafuzz, too, but I don't know if I needed it because the amp was breaking up really nice.

Gary Clark Jr. credits his rhythm guitarist Eric Zapata (left) for introducing him to his amp of choice, the Fender Vibro-King. Photo by Joe Russo

The SG sound on "Grinder" is even bigger and more unhinged, especially in the solo—it's barely controlled feedback.

Definitely, man. For that, I just thumped on the wah and left it all the way open, which is quite rude. It's not nice at all, very unapologetic. It's the same combo as “The Healing," but I'm all the way up.

Did you work the “Grinder" solo out, or was it all one spontaneous pass?

I originally did a solo that was a little bit nicer. [Laughs.] We were just sitting on it and I was like, “Let me get one more. Let me just go in here and see what happens." We just turned it up and I went through it again. I didn't think I could get it any wilder, any ruder, so that was the one we stuck on the record.

I love your clean rhythm playing on songs like “Cold Blooded" and “Star"—so Curtis Mayfield. What's your recipe for that approach? Is it all in the hand, or is it the guitar and the settings?

It's a combination of everything. I played the rhythm stuff for those songs on the Strat—very clean, no crazy effects, just reverb and a little bit of wah. I really just wanted to explore that clean thing. I mean I grew up on soul and Motown and stuff like that. That Strat thin tone really resonated with me. I just went in there and worked it out. When I listen to some of these songs and sounds, I think that maybe I wasn't born in the right decade.

How's that?

When I listen to them, I picture Marvin [Gaye] in the '70s. He's as much of my roots as Jimmy Reed. Curtis Mayfield, too. I think that's more apparent on this record. I feel like my musical style is a little bit throwback, but I'm trying to move it forward and bridge some sort of a gap. You know, I love Dr. Dre and RZA, too.

Do you record more of the soulful songs at a particular time of day? Like, “Okay, at 4 o'clock in the afternoon I'm in a rude mood for soloing. At 10 o'clock I'm more relaxed and it's time to do some mellow rhythm work."

It's actually the reverse. I'd say before midnight is when the rhythm stuff happens. I try to have some discipline, get into a different mindset. I'll think, “How would Jimmie Vaughan play this?" It's like, “How chill can I possibly be?" You just vibe out. After midnight, that's when you're prone to try out new things. That's when you get a “Grinder" solo.

Recently, you came out with your signature Epiphone guitar, the Blak & Blu Casino. Where are we hearing that on the record?

That's on “The Healing," along with the SG. The little bit of vibrato is the Casino. You hear it on “Star" a little bit, too. You can barely hear it, but that fuzzed-out, sitar-y little thing— that's the Casino.

YouTube It

Gary Clark Jr. gets into an especially nasty soloing mood during this extended version of “Grinder" at the 2015 Toronto Jazz Festival.

Do you have a different attitude when you play a guitar that bears your name versus another guitar you've had for years?

That's a good question. I definitely look at it more. [Laughs.] I'm like, “Wow, I can't believe this actually happened." While I'm playing it, I'll be sitting and I'll have it on my lap, and then I'll just put it on my knees and look at it. “Man, that's pretty cool." It's a different feeling, for sure. I'm proud of it.

Where do you see yourself in 10 years as a guitarist?

I'd like to have a better understanding of how chords and notes really work together because, quite honestly, I don't have much of a music education other than, “Put your finger here. This makes this chord," or whatever. I've pretty much just figured out different scales and tunings. I feel like I've only really tapped into a small bank of what guitar is really capable of.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)