In the time it takes to read this story, another US serviceman or servicewoman will lose their life. It won't be to an IED on the battlefields of Iraq or Afghanistan. It will be to suicide on the battlefield of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and depression—right here at home. Every day, 19 soldiers take their own lives. Fifty percent of our homeless population is made up of veterans, and more than 250,000 veterans now suffer from PTSD. A 2004 Department of Defense study estimates that 17 to 20 percent of soldiers returning from Iraq “suffer from major depression, generalized anxiety, or PTSD." And according to a 2008 report cited in Tears of a Warrior: A Family's Story of Combat and Living with PTSD—a book the Veterans Administration uses in its PTSD treatment program— roughly 40,000 troops have been diagnosed since 2003.

It's easy to slap a "Support Our Troops" magnet on the back of a vehicle to show solidarity in times of deployment, but where is that support when these men and women come home physically and emotionally broken? Where do they turn when society is not informed or empathetic enough to understand their state of mind, or when they are shamed into silence by the stigma of "mental illness"?

These are crucial questions too often left both unasked and unanswered. However, two guitarists with their hearts in the right place are doing their best to make a difference. Guitar instructor Patrick Nettesheim and guitar-playing Vietnam War veteran Dan Van Buskirk decided to take matters into their own hands by creating Guitars for Vets (G4V), a unique form of music therapy they're taking to VA medical centers.

Founded in 2008, Guitars for Vets is a nonprofit that provides six free, one-on-one guitar lessons and a new acoustic guitar to veterans in recovery. Its mission is simple: Turn the guitar into a source of healing, communication, and self-expression. Veterans enrolled in the program receive their own new Oscar Schmidt acoustic guitar at their sixth lesson, and thereafter they can continue learning through group lessons. G4V began in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, but has chapters in several other states—as well as one in Afghanistan—and it's receiving requests from VA centers across the country. Six strings at a time, it's working miracles.

To Hell and Back Again

Van Buskirk and Nettesheim met in 2007, when Van Buskirk became Nettesheim's guitar student. It was a fortuitous step on the long road to recovery for a lifetime pacifist who joined the military to uphold family duty.

Although the Peace Corps was his first calling, Van Buskirk joined the Marine Corps and became a reconnaissance scout and sniper during a time when, he says, "We were a bunch of young men confused by John Wayne movies, masculinity, and serving your country. I was assigned to Albrook, the hottest, best team battalion. We were on patrol schedules in Laos, and it was so dangerous that all the guys left letters and valuables for their loved ones because no one expected to return alive. Because Albrook was so good, the whole team would go on patrol. Except they wouldn't let me go—I was too inexperienced. One day, the North Vietnamese set up an ambush for Albrook. They shot down the helicopter with a rocket and all the guys died."

During Van Buskirk's 1968-1969 tour, he did 40 patrols in Laos and Cambodia, lost his best friend there, and witnessed unspeakable horrors that remain with him today. Upon return, he was hospitalized for a year and told he had "shell shock," as it was called then. "They didn't know how to treat it," he says. "I was in a deep, deep depression. You feel like you are in a black tunnel that has no light on the other side. I just wanted some light, but I couldn't see it."

Van Buskirk struggled to maintain a normal life. He married, became a father, worked, and went back to school to earn degrees in sociology and anthropology. Though he attempted to become an adjusted civilian, Vietnam never left him. "I mostly had a sense that 'I just don't get it,"' he says. "It plagued me. Some people live joyously, but for veterans with PTSD, we're in survival mode." Van Buskirk still experiences flashbacks and nightmares.

In 2005, after losing two jobs, Van Buskirk was placed on full chronic disability. As part of his search for ways to deal with depression, he bought a guitar. He had tried playing years before, but lacked focus due to PTSD. Cream City Music, in Brookfield, Wisconsin, recommended Nettesheim as an instructor. The lessons became educational for both men: Van Buskirk learned to play, while Nettesheim learned about Vietnam and the struggles returning veterans faced. They realized they were on to something.

Guitars for Vets debuted in the Milwaukee VA spinal rehab unit, where Van Buskirk and Nettesheim performed for paralyzed veterans whose lives are spent in wheelchairs and on their backs. "Dan played 'Knockin' on Heaven's Door' and we saw guys who had been staring at the ceiling for 40 years just light up," says Nettesheim. "The smiles, the happiness—they would hold the guitars while I strummed them. I knew it was magic. These men with broken bodies, broken spirits, and no way out of their situations as prisoners of their own bodies—I saw the light in their eyes." During their next lesson, Van Buskirk and Nettesheim put a plan in action and created Guitars for Vets.

Asked to explain the source of that rekindled light—why the guitar is a source of comfort— Nettesheim says, "How you hold it against your midsection—it's a metaphoric shield. When you look at trauma as part of the human condition, in moments of sadness and weeping, you rock back and forth and hold a pillow or a teddy bear to your midsection. It's an innate trait. The guitar is a good surrogate for that. It allows you to speak without words. The cool thing with the guitar, and many instruments, is the universal language: Others get what you're feeling by what you play. It helps us communicate emotions that may be too difficult to verbalize. That's why music touches so many people deeply."

Faces of the Faceless

A group of vets from the St. Louis, Missouri, chapter of G4V gathers to socialize and support each other through song.

Photo by Glen Harris

Miami resident John Miranda understands using music in place of words. He spent a good portion of his adult years entrenched in the rock-musician lifestyle on the West Coast. In 1973, he joined the service and became a parachuter during the final stages of the Vietnam War. "Conflict and war are no picnic," he says. "Nor was the way we were treated when we came home. When I got out of the military, I began drinking heavily, jumped onboard with a band, and played my life away."

Miranda is now in his mid 50s, and not long ago he found the courage and the means to clean up his life. He went to the Miami VA for help in 2009 and met music therapist Elizabeth Stockton, whom he credits for not giving up on him during the hospital's three-month program. Through music and sobriety, he is learning to unlock emotions he believed didn't exist. "I know the power of music and what a program like this can do," says Miranda, who became the first instructor for the Miami chapter of Guitars for Vets. "There's life to music. It's very spiritual."

Guitars for Vets is staffed entirely by volunteers. Instructors must train through a strict VA program, and they're submitted to rigorous FBI background checks that require fingerprinting and official badges for admission to facilities. In addition to government protocol, G4V has three requirements. "Instructors must show gratitude toward veterans for what they have given," says Nettesheim. "They must be empathetic and sincerely able to feel these veterans' stories, and they must be nonjudgmental and throw all political thoughts out the door."

Marc DeRuiter instructs the Grand Rapids, Michigan, chapter of Guitars for Vets. A Navy veteran from 1972–1975 who was stationed in both the Philippines and Vietnam, he discovered the organization in 2009 through a web search. Based on his experience performing for patients in Alzheimer's Disease units for seven years, he understands the therapeutic effects of music. He has been a musician since his teens, and he has a repertoire of country, bluegrass, rock, and oldies tunes. He has performed with the same musicians for 30 years, and he began teaching guitar at his church 10 years ago. After discovering G4V online, DeRuiter says he emailed Nettesheim because he thought he'd be "a good fit." He explains, "Our philosophies are right in line with each other. I'm sold on the therapeutic value of music—you spend an hour a day doing it, and your body treats it like a workout. It relieves your stress. You practice until you get it right, and that provides a sense of accomplishment."

Marc DeRuiter (right), a Navy vet who served in Vietnam from 1972 to 1975, instructs Richard Pierson in a Guitars for Vets class at the Grand Rapids, Michigan, VA center.

Photo by Marc DeRuiter

For that reason, DeRuiter makes a point of teaching actual songs to his students right away, helping them through "He's Got the Whole World in His Hands" and "The Ballad of Tom Dooley." "If you've got a song, you've got something," he says. "Some of these veterans have never played guitar before, and they love it. They practice on their own and get together to practice too."

Nettesheim says that camaraderie is a crucial element of Guitars for Vets. "When you talk to veterans—especially combat veterans—they'll tell you that they miss the teamwork and close friendships they formed while in the service. When their tour is over, they often move on and never see each other again. They fight to protect each other's lives, and there is a great sense of loss when those relationships are gone. They go from the battlefield to being thrust back into civilian life. Concentrating on playing and practicing in groups helps them to stop thinking about their grief. Working together brings them feelings of family and belonging."

Dan Van Buskirk (right), a Marines reconaissance scout during the Vietnam War, took up guitar in 2005 after years of PTSD had ravaged his personal and professional lives. In 2008, he and his instructor, Patrick Nettesheim (left), formed Guitars for Vets.

Photo by Tim Evans

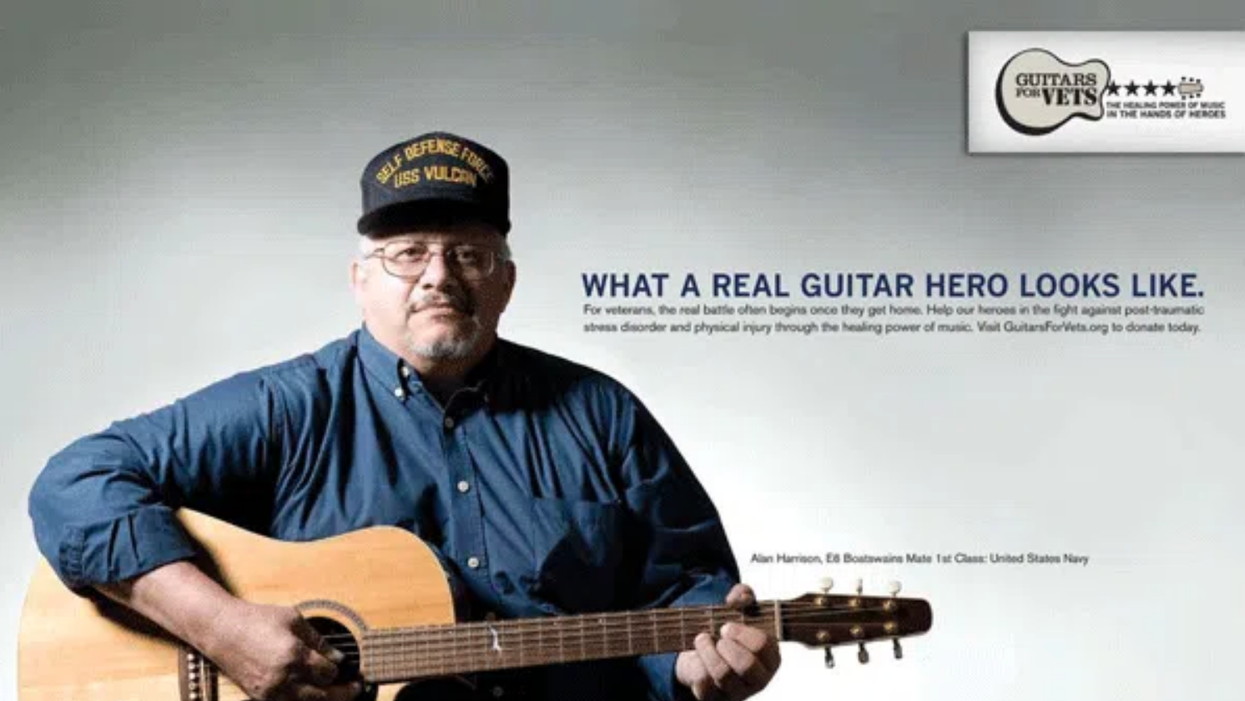

Alan Harrison, another Vietnam vet involved with G4V, learned about the organization through the Milwaukee VA hospital. He had played guitar as a teenager but gave it up when he joined the Navy, where he spent 21 years. He also suffers from severe PTSD. During his time in the service, he says, "I saw a man dismembered, sucked into the intake of a jet, and that wasn't the worst thing I saw."

When Harrison returned to civilian life, he couldn't erase his memories.

PTSD and depression had set in. Two years ago, he signed on for lessons with Guitars for Vets and now he's a volunteer for the program. "When I pick up the guitar, it takes me to a simpler time when I didn't have these memories," he says. "The guitar eases the pain. Without this program, I would still be in serious therapy. It helps me cope." (Visit myspace.com/guitarsforvets to hear "Dusty Old Road," a song Harrison and Meaghan Owens wrote about his experiences as a veteran.)

Of course, Harrison, Van Buskirk, DeRuiter, and Miranda are just a few of the countless veterans of past and present armed conflicts who suffer from the debilitating effects of PTSD. Van Buskirk expresses great concern for those who have served multiple tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. "I see a lot of men and women slip through the cracks when they come home. I see them get fired because employers aren't held accountable for dealing with soldiers with anxiety issues. I see things that sadden me," he says. "But a smiling face, a compassionate heart, a listening ear, and the vibrations of a guitar can help. I can't sit back and not be part of the solution. Medication is a useful band-aid but in no way helps the soldier get their soul back. If a soldier takes meds as the end-all be-all, they will miss out on getting their whole person back. If we take the lead with this program, maybe others will find it easier to help veterans—and maybe the VA will become more progressive and not just say, 'Increase your meds.'"

How to Help

Guitars for Vets has distributed over 600 guitar packs to date, but these instruments are purchased, not donated—and G4V incurs significant shipping costs to send guitars to its chapters. Each guitar pack consists of an instrument, a bag, and a tuner, and it is paid for by G4V, with the Oscar Schmidt acoustics being purchased at dealer cost. To date, no manufacturer has been willing to donate any instruments, so the organization relies on monetary donations from supporters. For the price of an evening out—dinner, movie, and drinks—you can help pay for one of these packs. Stay home one night and change a veteran's life.

Before receiving their free guitar at their sixth lesson, veterans enrolled in G4V learn to play on donated practice guitars. If you have an acoustic guitar gathering dust in your closet, send it in. Even if the instrument is no longer playable, artists associated with the program can turn it into an art piece that will then be sold to raise funds for G4V. Even if you don't have an old guitar to donate, you can help raise awareness of the program and provide useful funds by purchasing Guitars for Vets merchandise on the organization's website. There are other ways to get involved, too. G4V needs instructors and coordinators to set up new chapters and help with existing groups. Visit their website guitarsforvets.org or G4V's Facebook page for more details on the program and ways you can make a difference.

[Updated 11/10/21]

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)