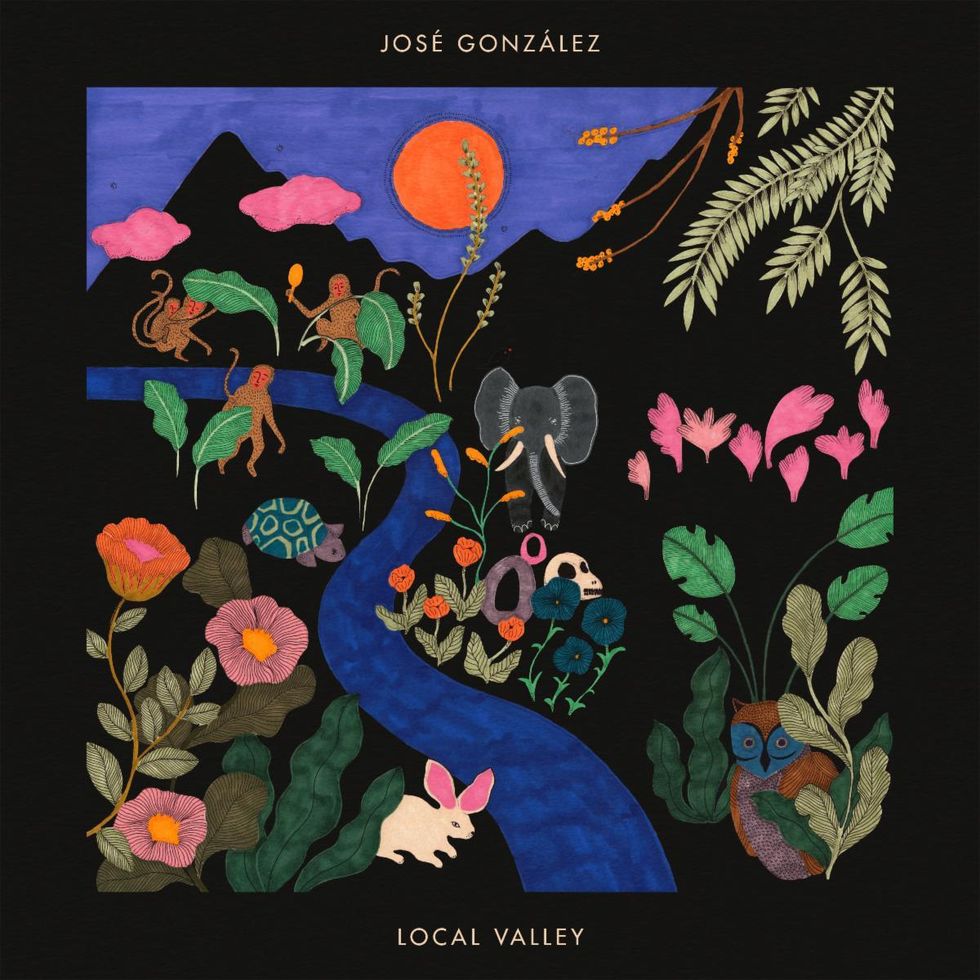

Acoustic guitarist José González doesn't give in to the fast-paced pressures of the music business. If you take a look at his discography, you'll see that the Swedish-Argentinian singer/songwriter has released just three solo studio albums in the past 18 years—the first having come out in 2003, when he was 25. (To be fair, he has also released two full-length albums and several EPs with his band, Junip, but most of these were put out in the '00s.) González turned 43 this year, just in time for the recent release of his fourth studio album, Local Valley.

"I wish I was faster, but I am slow," he says. "I feel like I'm doing a style of music that isn't trend-sensitive, so I think I'm allowed to take my time. Even if I wanted to push the pace, that would be a very unnatural rhythm."

José González - Line of Fire (Lyric Video)

Local Valley is anything but an interruption of González's natural rhythm. The collection of astral, quietly textural compositions for solo fingerpicked nylon-string guitar and voice evokes an ephemeral sense of solitude, creating its own realm in which listeners can, like González, distance themselves from external pressures. It's an extension of the same reality González designs for himself.

That's not to say that he hasn't had a full, successful career. His music has been placed in TV shows, including The O.C., One Tree Hill, Bones, House, and Friday Night Lights, and in 2011 he went on a tour with the Göteborg String Theory that spotlighted 11 arrangements of González's songs for orchestra. In 2013, he worked with Ben Stiller on the soundtrack of Stiller's remake of The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, which features González's solo work along with music from Junip.

"The existential lyrics are more acute now than they used to be, in a good way, because I'm comfortable with the finite nature of reality."

When discussing Local Valley, González reflects frequently on how he's changed as a musician over the years, both in terms of his approach to music and in his life philosophy. Out of everything, growth seems to be his priority. The album was wrapped in March 2020, and its release was put on hiatus for what has now been a year-and-a-half, due to the pandemic. But like the rest of González's work, it has a timeless quality that no doubt stems from that progressive mindset.

Existential Stead

The process of making Local Valley goes all the way back to 2017, when its songs were seeds, in the form of early demos. The following year, González got a residency at an artists' retreat in Grez-sur-Loing, France, where he decided he was going to begin more seriously writing and recording. There, he composed almost half of the album.

TIDBIT: Like most of his solo albums, this year's Local Valley was recorded by González in his preferred setting—at home. That approach allows him to work at his own pace.

"I had an ambition to go back to my first album and do short songs that were pretty melodic and guitar-oriented. Once I had those songs, I allowed myself to experiment a bit, put the producer's hat on, and not so much be the one who wants to impress people with just this one guitar." He decided to use a looper for some of the tracks, and on the songs "Tjomme," "Lilla G," and "Swing," he used a drum machine—which he says he's always wanted to do. Using the two devices also allows him to create more layers that he can effectively recreate alone when playing live.

During this timeframe, González and his partner, Swedish designer Hannele Fernström, purchased a summer house in Hakefjorden, an hour outside of his home city of Gothenburg, Sweden, where González was then able to record in a quieter environment. (All but his second album were home-recorded.) On songs such as "Visions" and "Lasso In," you can hear his field recordings of local birdsong.

Photo by Jim Bennett

The songwriter's guitars of choice are an Esteve 9 C/B and a Córdoba Rodriguez. The former is equipped with a Fishman Prefix Pro Blend pickup. Both guitars feature something else that's crucial to González's recording preferences: very old strings. "I try to vary how old they are for the different songs to get different sustain," he says. "There's something about the lack of treble that I like." A couple of González's other recording tricks include using a wooden percussion stomp box run through an octave pedal, and using a de-esser on the guitar—a favorite technique that takes away the "metallic-sounding frequencies. I'm allergic to 2 kilohertz," he says.

For the first time, González wrote lyrics in Swedish and Spanish—nearly half of the songs on the album are written in both of what he calls his native tongues. The use of the latter was influenced by his daughter Laura, who was born in 2017. When Laura was a toddler, he spoke to her in Spanish, which helped to keep the language alive in his mind while he was writing the album.

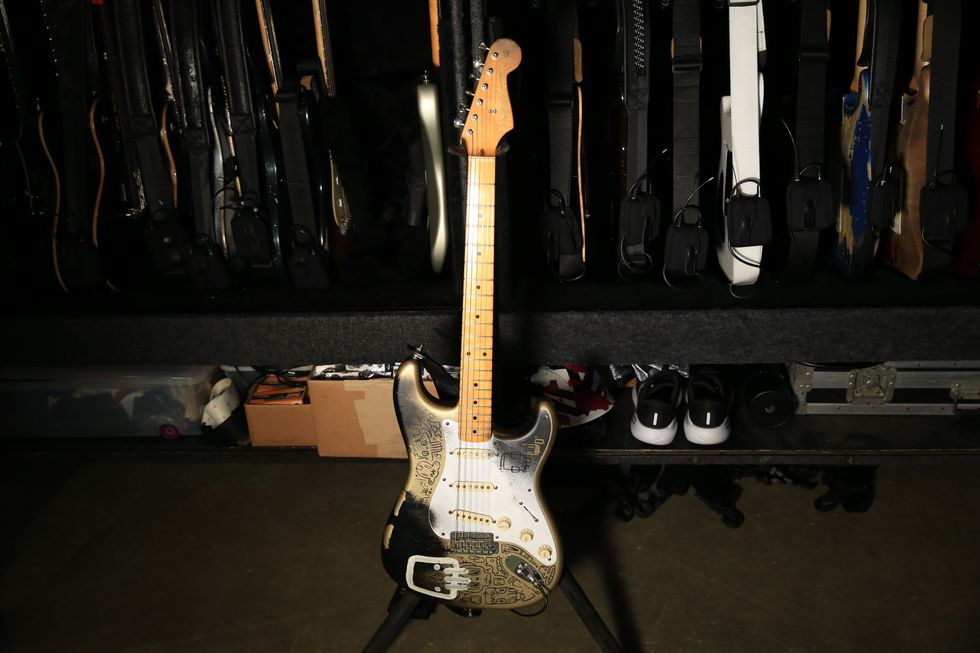

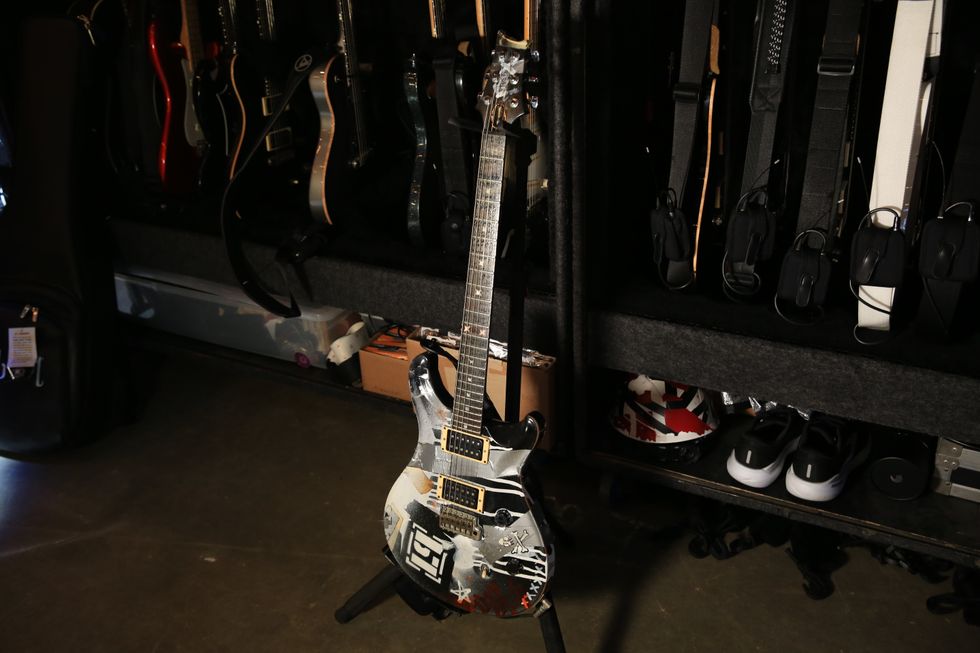

José González's Gear

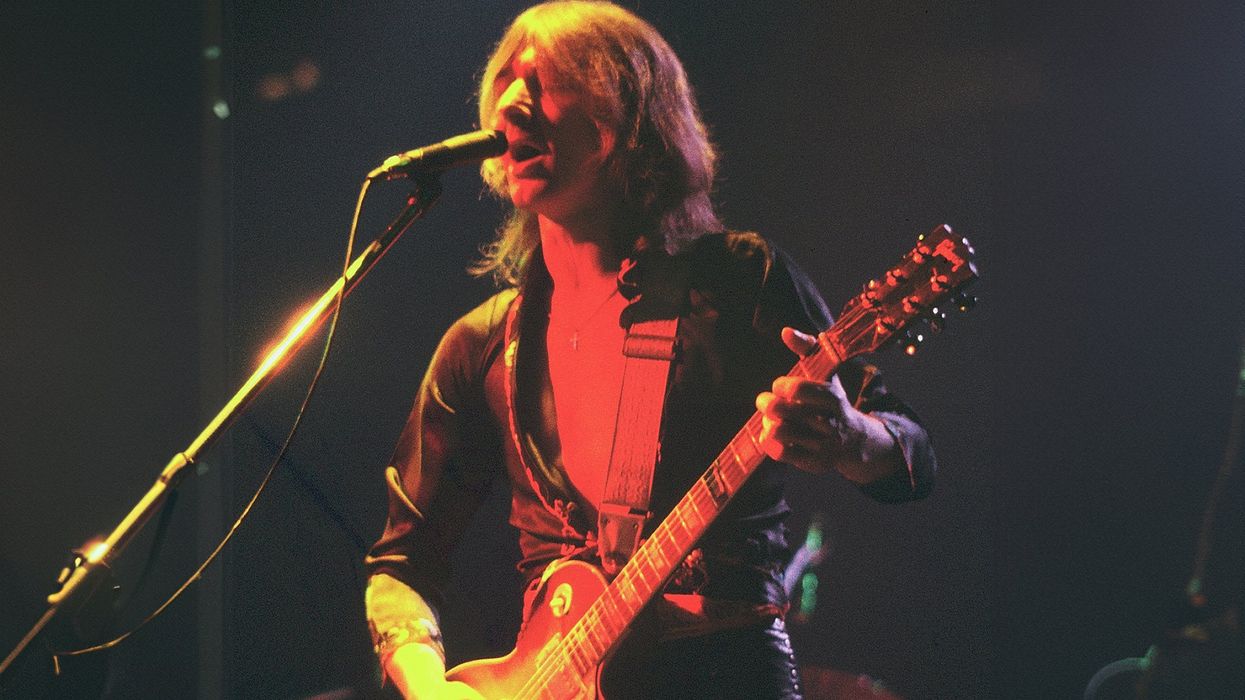

José González plays live at the 9:30 Club in Washington D.C. in 2015. González uses Fishman pickups in his nylon-strings and places duct tape over the soundholes to help control guitar tones when playing in large rooms.

Photo by Matt Condon

Guitars

- Esteve 9C/B with Fishman Prefix Pro Blend pickup

- Córdoba Rodriguez

Amp

- Schertler Jam (wood)

No matter the language, González's lyrics consistently match the nature of his music in their poetry and philosophical style. That's something that happens to have been influenced by Laura's birth as well. "Becoming a father and having parents that are getting older puts me in the middle of life position where I realize that I'm older than what my father or mother were when they had me," González expresses. "I think more about death than usual—not because I have to, but it just comes with the territory. The existential lyrics are more acute now than they used to be, in a good way, because I'm comfortable with the finite nature of reality."

Varied Voices

Before he got into guitar, González played the recorder and explored a Casio synth as a child. Then, around the age of 13 or 14, he and his friends discovered their passion for music. He began playing bass in a hardcore punk band called Back Against the Wall, and, at the same time, discovered his affinity for the nylon-string guitar. "I always felt like it sounded better to my ears than steel-string or electric guitar," he says. His dad, who used to sing in an Argentinian folk band, would ask González to learn songs by the Beatles and bossa nova artists like João Gilberto to accompany him.

By the time he began to record his debut, he was committed to the instrument. "I felt like everyone else was playing steel-string guitars and they were really into Americana, and I had my Latin-American roots," he says. "Also, the '60s, '70s folk singers from Sweden … all of them had Spanish guitars and there was something nostalgic for me with that sound—the lack of treble and sort of earthy sound."

"I write the guitar slightly above my skill level. I need my time to rehearse quite a lot."

The mindful, sedate colors of González's music are not so unlike those of English singer/songwriter Nick Drake—an artist González has often been compared to. González actually hadn't heard of the songwriter before his first album, up until one of the last songs he wrote for it—"Stay in the Shade"—which he says is essentially a "Nick Drake rip-off." His preference for very old strings is another thing he's borrowed from Drake.

Otherwise, González's influences tend to fall mostly outside of the realm of Western music, stretching globally to include the leader of the Nueva Trova movement, Cuban guitarist Silvio Rodríguez; the Argentinian singer Mercedes Sosa; Brazilian composers Caetano Veloso and João Gilberto; and jazz singer Monica Zetterlund and jazz pianist Jan Johansson, both Swedes. On Local Valley, says González, you can also hear the influence of West African guitarist Ali Farka Touré, the Tuareg band Tinariwen, and Tuareg singer/songwriter Bombino. "Valle Local" and "Head On," from the album, happen to be inspired by a jam session with Bombino, says González. He adds to the list Ghanian high-life, dance-oriented music from Congo, Afrobeat from Nigeria, and raga Bhoopali.

González's recording strategy included making field recordings of the birds around his home, and those appear on several of Local Valley's tracks, including "Visions" and "Lasso In."

Then—and we're still talking about influences—there's economics. "From the second album and on, I started to let myself be inspired by books and not only write about internal feelings, but more about an extroverted view on the world," he elaborates. "I try to push myself into not falling into cliches in terms of ideologies, but really try to understand difficult subjects, including economics. I've been reading [books by economists] Joseph Stiglitz, Mariana Mazzucato, and Angus Deaton." The song "Head On" mentions rent seekers and value extractors, concepts that González says have negative connotations on both the right and left. He says it was his ambition to write a song that was angry without being irritating to listeners of either political leaning.

Aural Analysis

González is not what you'd call a prolific songwriter, and that's something he's perfectly comfortable with. He likes to take his time, to the point where, when working on The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, his gradual approach caused Stiller to adapt from his original idea of having González write the entire soundtrack to instead inviting in another composer, Teddy Shapiro, to complete the score. (González is featured six times on the soundtrack: four times as a solo performer and twice with Junip.)

Particularly with his solo music, González says, "I write the guitar slightly above my skill level. I need my time to rehearse quite a lot, and that's one of the main reasons why I'm slow. I set the bar a bit higher than my skills." He crafts his guitar parts somewhat analytically—something he relates to his experience of having pursued a PhD in biochemistry before he devoted himself to his music. "I do a lot of trial and error before I have my final product."

González performs on the Bigfoot Stage at the 2015 Sasquatch! Festival in George, Washington. He was accompanied by a percussionist for a set mostly of songs from his first solo album.

Photo by Debi Del Grande

"I have my different tunings and that allows me to not think in terms in chords, but to think in bass lines and arpeggios," he continues. "Nick Drake has been a big inspiration in terms of tuning and using the thumb to do the bass, and having arpeggios to do the body of the song. Then I always think about the highest note as an extra melody. That's how I try to make the song as dense as possible with only one guitar." González uses a variety of alternate tunings. On "El Invento," the tuning is in drop D. On "Visions," it's D–A–D–A–B–E. Other tunings on the album include E–A–D–A–B–E and B–A–D–A–B–E. He also has a proclivity to avoid the third—"either major or minor." Although, "Nowadays, I'm more okay with major chords—but I'm still avoiding minor."

Over the years, González has simplified his songwriting process. He says he used to follow a set of rules, inspired by Danish film directors Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg, who set limits and edicts for how they could make films with their director-centric "Dogme 95 Manifesto," created in 1995. Two of González's primary rules are not writing verse-chorus-type songs, in favor of more linear writing, and avoiding using "me" or "I" in the lyrics.

But if the gentle, organic progression of his career says anything about González, it's that he's eased up quite a bit on himself since he started out. "Since then, I've been okay to not have any rules," he says. "Nowadays, I'm just happy to make things up."

José González at Michelberger Hotel - Jim Beam Welcome Session #3

José González is well in form as he performs "Valle Local" from his new album, showcasing his expert fingerpicking on nylon-string guitar while accompanying his softly sung vocal.

Miller’s Collings runs into a Grace Design ALiX preamp, which helps him fine-tune his EQ and level out pickups with varying output when he switches instruments. For reverb, sometimes he’ll tap the

Miller’s Collings runs into a Grace Design ALiX preamp, which helps him fine-tune his EQ and level out pickups with varying output when he switches instruments. For reverb, sometimes he’ll tap the