Few bands have had careers as charmed or as unlikely as Los Lobos, and even fewer have successfully laced together the number of disparate styles found in the band's music to make such a unique yet cohesive sound. Los Lobos' blend of traditional Mexican folk, soul, blues, and roots rock is a direct reflection of the diverse musical environment they were immersed in coming up in East Los Angeles in the late '70s and early '80s. The band's voice has always mirrored L.A.'s eclectic sonic tapestry in a beautiful and authentic way, and in an era where the internet can sometimes dramatically homogenize how we make art by removing geography and local interaction from the process, Los Lobos' uncanny story and locally shaped sound are a reminder of bygone days.

They are a living, breathing, culturally significant remnant of a fast-disappearing version of Los Angeles—and one with a legacy much bigger than just their brilliant work on the La Bamba soundtrack—elevated by a unique personality and rendered in fabulous songs. The diversity which shaped Los Lobos' music has always made L.A. fertile ground for guitar culture, and a deep passion for the instrument has always underpinned Los Lobos' work.

The group's pair of guitar and vocal anchors, David Hidalgo and Cesar Rosas, have earned no small number of famous friends and fans in the guitar space over the years—including heavies like Billy Gibbons and Eric Clapton—and when Hidalgo is brought up in guitar circles, the conversation inevitably turns to how underrated a player he is. Despite the stout, soulful chops and deceptively difficult rhythms that lurk within Los Lobos' songs, guitar heroism has never been this band's bag. Los Lobos' odyssey has been a decidedly blue-collar affair that always put the songs first, from performing traditional Mexican folk tunes for punk audiences while opening shows for bands like Black Flag, X, and the Blasters in the early '80s, to sharing the stage with roots-rock greats and jamming with their heroes. Most importantly, Hidalgo and Rosas have learned from it all, remaining dedicated students of the various musical traditions that have influenced their sound.

Los Lobos - “Native Son” (Official Music Video)

Check out the title track from the band's 17th album.

Now, Los Lobos is looking back. Their latest album, Native Sons, is an unsurprisingly varied collection of cover tunes, which traces the band's early education and love affair with Southern California's music culture. "We went through hundreds of songs when we were choosing the songs for the album, and we took it back to the basics," David Hidalgo explains. "Everyone chose songs that meant something to them, so a lot of these were our breakthrough tunes, you know?"

The resulting recording is not only a fantastic primer on California's best music as Los Lobos sees it, but a prime example of this band's ability to take on just about any tune and make it their own without sacrificing what made the song charming in the first place. Hidalgo and Rosas are all-too-happy to discuss the music that shaped them as players and songwriters while growing up in Southern California during the glory days of AM radio. Hidalgo sets the scene for us.

"Growing up in L.A., everything was everywhere," he says. "You'd drive through all these different neighborhoods and you'd hear different music. The AM radio back then was great—it was wide open. You had rock 'n' roll like Chuck Berry, the Beatles, the Stones, the Animals, the Yardbirds, but also you had Stax stuff, like Sam & Dave and Otis Redding, and Motown. Then you had the Mexican music that was everywhere, from the mariachis playing in restaurants to all these different styles. So, it all made sense to us. My older brother was a drummer and he'd play weddings, and his band had to play everything. They'd play 'Time Won't Let Me' by the Outsiders and then they'd play a cumbia, or they'd play some Chuck Berry before playing a bolero. That was the tradition we grew up in. L.A. had T-Bone Walker and its blues side, but surf guitar was also born in Southern California, and you had guys like Dick Dale, and the South Bay had bands like the Pyramids and the Belairs. So, it was always diverse. On top of that, Fender came out of Southern California and Semie Moseley started Mosrite in Bakersfield, so a lot of pioneering guitar makers were from the L.A. area and it was just part of the culture. The city was different back then, too. Neighborhoods that are Black or Latino now used to be ranches, and there was lots of country music. The Wagon Wheel was a place owned by Joe Maphis in Norwalk, and you had honky-tonks 10 miles away from blues clubs where Bobby Bland was playing."

"When they threw us in that pool with Black Flag and the Circle Jerks and all those flash bands, shit man, we had to swim out of there!" —Cesar Rosas

Considering that Rosas met Hidalgo in junior high school, the pair's early musical interests were always closely aligned. However, Rosas found himself particularly drawn to the soulful side of things, which informed the airtight and colorful rhythm guitar work he excels at.

"Before I became a guitar player, I always took to a lot of soul and R&B music," Rosas says of his days as a nascent music fan. "In the AM radio days, KGFJ was my favorite station, and they played all Black music. So, I grew up listening to Aretha Franklin and Sam & Dave and the Memphis stuff, Booker T. & the M.G.s. And that meant I grew up loving guitar!"

The majority of Native Sons was tracked at Nest Recorders, which brought most of the band back to East L.A. from their homes in the suburbs, adding an extra layer of emotional weight to the process. However, since the record was cut during the pandemic, Rosas' contributions were tracked from the safety and comfort of his home studio in his "stocking feet," as he says. Rosas brought in album opener "Love Special Delivery"—a killer '60s rocker by Thee Midniters, an East L.A.-bred group that was among the first Chicano rock bands to have a major radio hit—and a sweet Willie Bobo ballad called "Dichoso," which Rosas finished with layers of fantastic yet delicate guitar work.

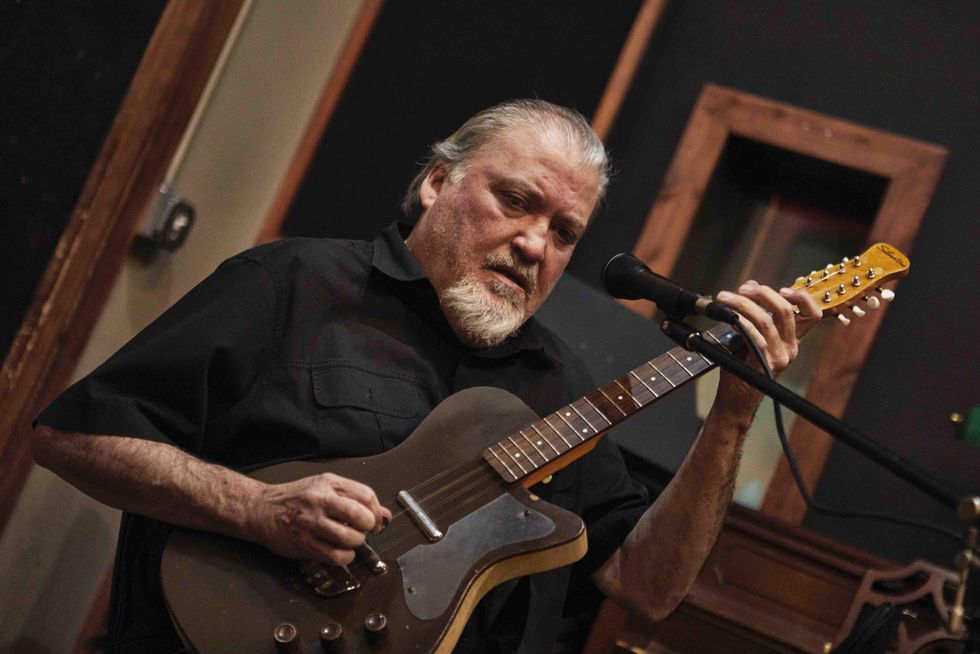

David Hidalgo's Gear

David Hidalgo plays a Silvertone during recent rehearsals for Los Lobos' Native Sons tour.

Photo by Piero F Giunti

Guitars

- Fender Custom Shop Nocaster

- Parts Telecaster with MIJ Body/MIM Baja Player Tele neck/TV Jones Filter'Tron in the bridge and humbucker in the neck

- '70s Les Paul Special

- '80s MIJ Fender Standard Strat

- Gibson Chet Atkins nylon-string solidbody

- 2000s Gretsch '59 Country Gentleman single-cutaway reissue

Amps

- Vintage Fender Deluxe Reverb

- Fender Pro Junior

- Modified Bell & Howell Projector amp

Strings & Picks

- Ernie Ball Slinkys (.009, .010, or .011 sets, depending on guitar)

- Herco .75 mm silver

Hidalgo's selections boast some of the album's standout guitar moments. He sought to honor the spirit of originals as closely as possible with his performances. "I've always been a guitar lover, so 'Bluebird' by Buffalo Springfield was one of mine. Between Neil Young, Stephen Stills, and Richie Furay, it has great guitar playing, great arrangements, and great tones. That was a song I've wanted to play since I was 16 years old, but it was always too hard."

The band's cover of War's "The World Is a Ghetto" features some of the finest guitar playing and tones on the album. Hidalgo claims it was a deceptively difficult track to get together, even for a decorated player such as himself. "It's one of those songs we grew up with, but you don't realize how intricate it really is until you start trying to play it," Hidalgo says. "Howard Scott's guitar playing is elusive. There's hard rhythms and he's riffing on it at the same time, and you can tell that band recorded that song live and in the moment, so they're not really set parts and they change throughout the song. So, I tried to at least cop that vibe."

TIDBIT: Los Lobos' 17th studio album, Native Sons, was recorded during the pandemic at L.A.'s Nest Recorders studio, except for guitarist Cesar Rosas' parts, which he tracked from the safety of his home studio in his "stocking feet."

The closing jam on the War cover flexes one of the rare moments on the album where the group allowed themselves to cut loose from an original arrangement. "The ending of that song always sounded like it went to the relative major to me, so we went into this almost Hendrix or Sonny Sharrock-like solo," says Hidalgo. "The end of that one was our chance to break it open and do our own thing a bit."

While the gear and amenities available at Nest were put to good use by his bandmates, Rosas had no shortage of killer gear at his disposal at home. The southpaw guitarist has amassed quite the collection of rare, vintage left-handed guitars over the years, many of which never leave his home studio, so the circumstances presented a rare opportunity to put them to work.

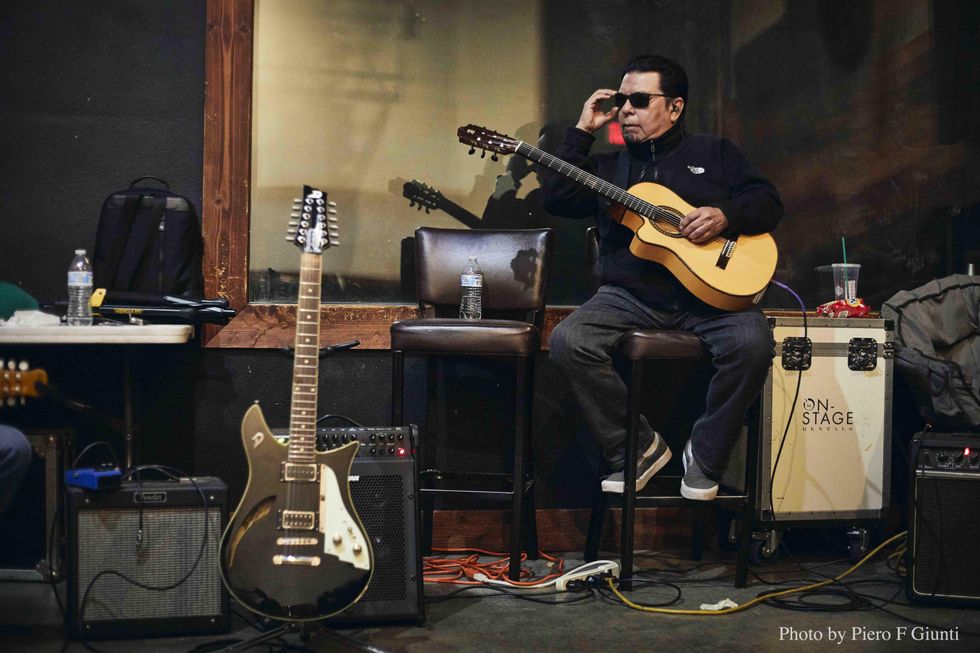

Cesar Rosas' Gear

Cesar Rosas stands by with a southpaw Candelas nylon-string during recent rehearsals for Los Lobos' Native Sons tour.

Photo by Piero F Giunti

Guitars

- 1952 Gibson ES-295

- 1960 Fender Stratocaster

- 1966 Fender Telecaster

- 1960s Gretsch Country Gentleman

Amps

- 1950s Fender tweed Deluxe

Strings & Picks

- Ernie Ball Slinkys (.009–.042)

- Clayton Triangle 1.0 mm

"I have my special gear that I keep at home, my vintage guitars and vintage tweed Fender amplifiers that I only use at home for recording," Rosas says. "'Dichoso' has three or four guitars overdubbed on it. I used a 1952 Gibson ES-295 and a 1960 Strat that's very dear to me. I recorded 'Love Special Delivery' with a Gretsch Country Gentleman and a 1966 Fender Tele. And I used an old '50s tweed Deluxe for those songs."

Hidalgo and Rosas have always brought their own unique playing styles and gifts as guitarists to Los Lobos' music, but one thing that's unified the duo is a love of gear and the endless hunt for tone. When asked if there's still tonal experimentation in the process after this many records, Hidalgo is emphatic about how much he enjoys that side of things. "Oh yeah! That's the fun of it and that's what keeps you doing it! It's gotten a lot simpler. We used to take 30 guitars and a bunch of amps to the studio, but we got it down to a hollowbody, a Les Paul or an SG, a Strat, a Tele, and a couple of old amps, like a Deluxe Reverb. There are ways to get a lot of sounds out of minimal gear. For amps, I used Deluxe Reverbs for cleaner sounds and I'd combine it with a Fender Pro Junior a lot, which sounds like an old tweed amp to me."

For Rosas, he'll take the real deal over hybrids any day. The self-proclaimed purist says, "Sometimes somebody throws an oddball guitar at me and I play it for a little while—like I had a Strat with a humbucker in it—but I eventually go, 'What's the point? I'll just play a Les Paul.'"

"We were playing a college in Madison, Wisconsin, once and there were a lot of young punk kids and they were having fun slamming, so we broke into this Mexican ballad and they started doing the same thing in the pit, but in slow motion." —David Hidalgo

The story of how Los Lobos fell in with L.A.'s emerging punk scene when the band was still performing traditional Mexican folk songs is more than just an unexpected detour. It's a tale that underlines how truly open-minded the early punk scene was. And it's a story that proves there are things to learn from all types of music if you're paying attention. Hidalgo and Rosas both look back on those days fondly. "There was no posing with those guys, and if it was real, people in that scene were open to hear what you had to do or say," Hidalgo remembers. "The sense of community, too. In the '80s, all the bands in L.A. supported each other. The Blasters asked us to open a show for them at the Whiskey a Go Go, and that was the stepping-stone that got us going, really. There was friendship, camaraderie, and respect for each other that made the L.A. scene special. We just kind of sped everything up a little bit so you could slam to it! We were playing a college in Madison, Wisconsin, once, and there were a lot of young punk kids and they were having fun slamming, so we broke into this Mexican ballad and they started doing the same thing in the pit, but in slow motion. It was fun and most of us were on the same page: If it was real and authentic, it didn't matter what it was. Everything is connected for me and that's what I draw from."

For Rosas, the way the punks approached guitar was powerful. "Just the way those guys played—they were fuckin' on fire! A lot of them just plugged straight into the amp and that hit home for me, and it rubs off on you," Rosas says. "It's just sick stuff and we could relate to that. When they threw us in that pool with Black Flag and the Circle Jerks and all those flash bands, shit man, we had to swim out of there! But we were into it with everybody and it was really cool! We're very lucky and very proud of our time in the punk scene. Those were very special times for us."

Native Sons' nostalgic spirit presents an opportunity to reconsider the band's journey, including the impact of their artistic breakthrough, 1992's Kiko. "That album was a turning point and a good time for us," Hidalgo recalls. "We had come so far, and on the album before, The Neighborhood, which I think is a great album and we did some good work on … but we had issues with the record company which soured the end result. It ruined the feel of the album because it ruined the enjoyment that we had doing it.

In this vintage photo, Los Lobos guitarists Cesar Rosas and David Hidalgo both play Strats at a gig circa 1984.

Photo by Debra Trebitz/Frank White Photo Agency

"So, when we did Kiko we needed something to fire us up again, and that's when we started working with Mitchell Froom and Tchad Blake, and they were in the same boat and wanted to shake loose from what they had done before with something they were excited about," Hidalgo continues. "That album means so much because we really learned how to use the studio with those guys. Kiko was the first time we went in the studio, wrote most of the songs in the studio, and changed the instrumentation and arrangements as we went. It really helped us get to the next destination as a band."

With so many years, critically acclaimed records, and wild experiences in the rearview, there's a lot for Los Lobos to be proud of, but the thing that brings both Rosas and Hidalgo the most pride is bringing Mexican folk music to new audiences and the tradition they've honored with their contributions to the form.

"The Wagon Wheel was a place owned by Joe Maphis in Norwalk, and you had honky-tonks 10 miles away from blues clubs where Bobby Bland was playing." —David Hidalgo

"The Mexican folk music we play is really challenging, and I'm really proud of when I can make that stuff happen," Hidalgo says. "You can compare it to bluegrass: Those players are so far advanced and you have to know that whole library of songs, but you have to have the chops for them. It's the same way with Mexican folk music, where it's a tradition and you have to be respectful to it, but at the same time, there's room to add your own voice and take it further. Folk music was made to evolve, you know?"

Rosas feels the same way, adding: "The legacy of the Mexican folk music that we carry is important. All of those rhythms and tough songs that we play—I'd like to be remembered for what we've done with that stuff."

Los Lobos - Kiko and the Lavender Moon (video)

This classic music video for "Kiko and the Lavender Moon," from Los Lobos' Kiko album (1992), showcases the group's unique fusion of Mexican folk music, rock, jazz, and other disparate styles.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)