<a href="https://firehouse12records.com/album/meltframe">Meltframe by Mary Halvorson</a>

Several years ago New York guitarist Mary Halvorson felt a schism in her playing. She'd developed an approach to playing jazz standards, and an entirely different set of strategies for free improvisation. This displeased her.

But one day after playing three sets of standards at a restaurant gig, Halvorson headed to an improvisation gig with jazz's harmonic/melodic language still in her head and used those materials outside of their usual confines to uncanny effect.

Halvorson takes a similar approach on her latest album, Meltframe—her first solo-guitar effort, and a project that required three years of introspective study. Aside from the Duke Ellington piece “Solitude," she interprets music outside the standard repertoire: pieces by Annette Peacock, Chris Lightcap, Roscoe Mitchell, and other improvising composers, all of it written between the 1960s and the recent past.

Halvorson, 35, has long been a fixture in new-music circles. She entered that world via studies with iconoclastic multi-instrumentalist/composer Anthony Braxton when she was a Wesleyan University student in the late '90s. Based in Brooklyn since 2002, she's lent her singular voice to the ensembles of bandleaders like Tim Berne, Taylor Ho Bynum, Myra Melford, and Jason Moran, and she's worked with prominent guitarists like Marc Ribot, Bill Frisell, and Joe Morris.

A strong bandleader and composer in her own right, Halvorson leads a long-running trio with bassist John Hébert and the drummer Ches Smith. The trio also serves as the core of larger ensembles, often with unusual instrumentation—such as an octet with pedal-steel guitar. She also plays chamber-jazz duets with violist Jessica Pavone and avant-rock with the group People.

Halvorson spoke to us recently about the challenges of assembling a solo-guitar set, the joys of pairing distortion and delay effects with a traditional jazz box, and the lessons learned from her teachers and collaborators.

How did you get into jazz—were you always a fan, or did that develop with experience?

No. I played Suzuki [method] violin from about second grade to seventh grade, but I didn't like it much and wasn't great at it. At that time I was getting more into rock music—Jimi Hendrix, the Allman Brothers, things like that—so it made more sense to switch to guitar around seventh or eighth grade. I started with rock music, teaching myself out of tablature books. Eventually I found a teacher, Issi Rozen, who happened to be a jazz guitarist, so it was more by chance than anything that I started learning jazz.

You grew up in Boston, a city known for its music schools. Did you study at Berklee or the New England Conservatory?

I didn't go to college at either school, but NEC had a preparatory program for high-school kids, and Berklee had a summer program I used to do, as well. Boston was a cool place to be for those reasons. After high school I went to Wesleyan University, where I got more serious about music. I studied with Joe Morris on guitar, and Anthony Braxton as a kind of all-round inspiration.

What was that like?

With both Joe and with Anthony, there was a lot of emphasis on exploring, taking risks, and finding your own voice. The point really got hammered into my head. With Anthony, it was inspiring to get a glimpse into his expansive musical world. He's created a completely unique world while having great respect for all types of music. That was really important to me: being open-minded about all styles.

How did you find your own voice? Did you consciously synthesize those influences, or did it happen naturally?

It was both. I would listen to their music and see that they both had a strong thing that was truly theirs. But when I started studying with Joe, he would never play guitar in the lessons—he didn't want me to copy what he was doing [laughs]. He would play upright bass instead, and we would do a lot of improvising together. It was like, “You're studying with me, but that doesn't mean you're here to learn all the things I'm playing." He encouraged me to explore on my own.

Meltframe is your first solo album. How did it come about?

Over the years, people have often asked me, “When are you going to do a solo record?" But until recently I didn't really have a strong concept for solo guitar, and I didn't want to make an album just for the sake of doing one. I didn't want to do an all-improvised album, and I had no inspiration to compose for solo guitar. A lot of the composing I've done has been for larger projects—that's where my compositional brain has been for a while.

How did you select material?

I'm not a “tunes" player, but I practice a lot of standards for technique and to expand my knowledge of harmony. So arranging standards for solo guitar seemed natural. But pretty quickly I expanded beyond standards to any pieces that I like—compositions by friends, or things a little outside the standard repertoire, like the Roscoe Mitchell or Annette Peacock tunes I included. I gradually expanded that repertoire until I was ready to do some gigs with the tunes and record them.

What links the pieces?

The originals are so vastly different in style, so I guess the link is that they're all songs I loved at some point and spent a lot of time listening to. Like “Cascades" by Oliver Nelson: In high school I used to listen to The Blues and the Abstract Truth [which includes “Cascades"] all the time. There are also songs that got stuck in my head that I found myself going back to again and again. A few I listened to all the time in college, like Annette Peacock's “Blood," which I transcribed from a Marilyn Crispell record—a cover of a cover. Then there's more recent work, like the Chris Lightcap piece “Platform."

YouTube It

Before hitting the studio to record Meltframe, Mary Halvorson tests her solo set on a live audience while opening for Melvins' Buzz Osborne in Baltimore.

Did you encounter any challenges?

There was a ton of challenges. It's funny—everyone who's ever played solo guitar talks about how difficult it is, so I was kind of prepared for it. It's a really different mentality. If you're having a bad day playing with a band, there's a bit less pressure—if you're not playing great, someone else might play something amazing, which can inspire you to take it up a bit. But when you're playing solo, it's just you. It's a little nerve-racking.

How did you solve the problem?

I would record myself and then listen back. In the beginning I found that I wasn't leaving any space, almost like a nervous talker. It felt like I was talking to someone but not saying anything—just anxiously blathering. I had to work on pacing and letting the music breathe, which took quite a while. The other challenge was to make each piece sound different, because it's just solo guitar—just one sound. I tried to create diversity and have the pieces fall in as broad a range of techniques and arrangements as I could, so it wouldn't feel like everything was in the same style with the same approach.

Your sound is so lively. Was the guitar body miked as well as the amp?

Yes. I always put a mic on the strings, because my guitar has a really nice acoustic quality, and I blend that with a mic on the amp—a Princeton Reverb. And we usually use a room mic on everything.

Did you use the Guild Artist Award hollowbody you've played live for years?

Yes. I found it in 2000 at a shop in New Jersey. At that time I was studying with a guitar teacher named Tony Lombardozzi at Wesleyan. He told me about that particular model, and then I managed to find one, though vintage ones don't pop up that often. I checked it out and really loved it. The guitar has a 17" body, a freakishly large headstock, and a loud, strong acoustic tone. I like having that acoustic quality, even though I play electric. It's a well-made, beautiful instrument that sounds great, and I've been playing it for 15 years now.

Though a vintage Guild is her go-to guitar, Halvorson also loves the custom flattop that New York luthier—and former repairman at Guild—Flip Scipio built her. It features a removable neck (for travel convenience), a vintage DeArmond pickup, and specs designed to feel and respond like Halvorson's Artist Award. Photo by Bruno Balleart

<a href="https://firehouse12records.com/album/meltframe">Meltframe by Mary Halvorson</a>

Tell us about your recently acquired custom guitar.

I started noticing that a bunch of upright bassists I play with have removable-neck basses, which make it easier to travel. It's usually fine to carry a guitar on a plane in a gigbag, but one out of 20 times it's not, and it's really stressful. So I thought, if bassists have instruments with removable necks, why can't I? I know an amazing builder—Flip Scipio–through a mutual friend. He's just brilliant and is into doing weird one-off projects, so I asked him a few years ago if he'd build me a guitar with a detachable neck, and got on his long waiting list. He designed my guitar to sound and feel as close to the Guild as possible—he actually used to work at Guild, so he really knows the guitars. It has a vintage DeArmond pickup and a neck that feels very similar. It's even got the same inlays, flipped around to look weird. It's a flattop with a slightly smaller body than the Artist Award. The neck comes off and the whole thing fits into a suitcase that I can carry on or gate-check. Being able to travel with an instrument I love has changed my life.

Is it difficult to pair those guitars with distortion like you sometimes do?

Not really. The only thing that gets tricky is if I'm playing loudly in a big place and feedback becomes is an issue. But I've managed to find ways to either control or work with it. Ninety percent of the time feedback isn't a problem—I think it sounds really cool having distortion while hearing bits of the acoustic tone come through.

Mary Halvorson's Gear

Guitars

1970 Guild Artist Award

Custom Flip Scipio flattop

Amps

1966 Fender Princeton Reverb

Effects

Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler

Mission Engineering EP1-L6 expression pedal

Pro Co RAT2

Dunlop volume pedal

Strings and Picks

Elixir Nanoweb strings (.012–.052)

Dunlop 1 mm Stubby picks

You use a Line 6 delay pedal in a cool, idiosyncratic way, making its skittering sound part of your vocabulary.

I got that pedal when I went to the New School's [New York City] jazz school for a year in the middle of college. I hadn't used effects much until that point. I think I got bored and wanted to experiment with sound. So I got a Line 6 DL4, probably because a lot of other guitarists had that pedal and seemed to like it. I started experimenting and found a way to make that sound like a pitch shifter or ring modulator. The cool thing about the Line 6 is that it has an option to use an external foot pedal. When I first started using the sound, I was turning the knobs with my hand. But when I got a pedal, I could to be hands-free and really integrate the Line 6 into what I was doing. Like the Guild, I've been using the Line 6 for 15 years. I've been through three or four of them.

There are great tremolo tones on “Solitude" and elsewhere on Meltframe, presumably from the Princeton.

I never really used tremolo until I got that amp six or seven years ago. A lot of times I do a sort of custom tremolo with the volume pedal—it's almost like playing sax and having different speeds of vibrato. But it's also nice to use the tremolo on the amp for a beautiful, consistent effect. And that amp has one of the best tremolos.

Some of the album's intense moments—like when you suddenly switch on the distortion pedal on “Aisha"—call to mind punk. How important is the rock canon to your improvisation?

It's important. Various types of rock music have meant different things at various stages of my life, but on the whole what I take from the music is its energy and edge. I sometimes feel like harnessing that energy, using simple power chords and triads and the percussive attack that certain rock guitarists use. I've always been interested in integrating these things into more jazz-oriented stuff.

Speaking of attack, yours is pretty enthusiastic.

I have a memory of first picking up a guitar and intuitively picking like that. It's always felt instinctive to play with a sharp attack. Also, I've always been drawn to upright bass, both the sound of the instrument and the way a bassist might really dig into the notes and have some buzzing sounds. That's why I like having a big acoustic guitar like the Guild and being able to hear the wood, the attack, and the natural sounds of the instrument.

Your use of slide on Ornette Coleman's “Sadness" is an interesting textural departure.

I love the sound of bowed bass and wanted to emulate it in some way, so I used a slide. Also, I'm really interested in pedal-steel guitar right now, and I've been writing for a group that includes a steel player. I used to play slide a bit in my early 20s, but not in any kind of idiomatic way—more as a sonic tool. Then I lost the slide and didn't buy another until a couple years ago, when I first became interested in pedal steel.

Let's talk about some of your other projects. In Ye Olde, led by trombonist Jacob Garchik, you match wits with guitarists Brandon Seabrook and Jonathan Goldberger.

That's been so much fun. Jacob's made these amazing arrangements for three guitars, trombone, and drums, and that band has a high level of energy and insanity—a crazy mesh of sound within the context of the arrangements. All three of us are pretty different guitarists. There's an element of us combining to sound like one massive guitar, but the differences come out in interesting ways because we're working both together and against each other, creating contrast and unity at the same time.

What it's like to work with Marc Ribot in his Sun Ship and Young Philadelphians ensembles?

Marc's one of my favorite guitarists and has been since I started listening to his music in college. Getting a chance to play with him has been amazing. One of the biggest things I've taken from working with him is that he's so incredibly in the moment. He's always taking risks. You're always on your toes when you play with him—you never know what's going to happen. And that's something that I've been able to take into other situations.

Meltmind: A Look Inside Mary Halvorson's Head

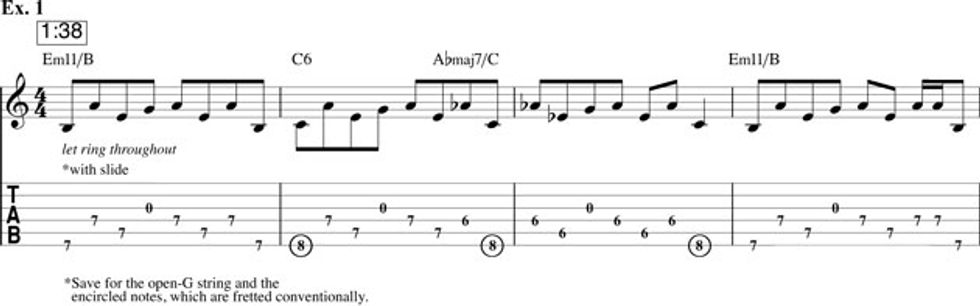

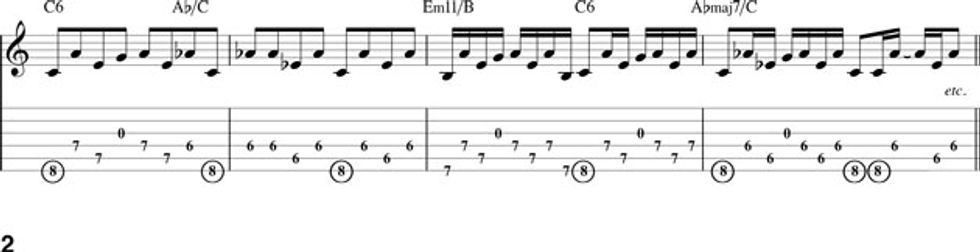

These three snapshots of Mary Halvorson's music show the wide territory her repertoire covers—both conceptually and technically—on Meltframe.

In her improvisation on Ornette Coleman's “Sadness," Halvorson employs a neat chord progression rotating around the open G string. With a slide on her middle finger, she reaches her fretting hand over the neck with her fingers pointed toward the floor. She frets the 8th-fret C with her first finger, letting the notes ring together. The G creates timbral contrast against the slide notes.

Halvorson opens her interpretation of Oliver Nelson's “Cascades" with a commanding, angular solo. It emphasizes the biting sonority of the minor ninth (Db) and demonstrates her penchant for combining distortion with her Guild archtop's natural acoustic sound. Note the judicious use of silence.

Halvorson plays Duke Ellington's “Solitude" at an impossibly slow tempo. In her solo, she improvises a new chord progression with pared-down harmonies. Her Fender Princeton Reverb's tremolo makes her spare chord-melodies seem to sing.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)