In January 1997, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers’ 20-show run at the Fillmore fostered a village, a sense of communion, and something even rarer in the hyper-connected 21st century—organic, word-of-mouth buzz and street chatter. For me, it was a sort of homecoming, too. By ’97, I was a voracious musical omnivore, feasting with the maniacal vigor only a 20-something can muster. But though I was weaned on the stuff, very little of my intake in those days could be filed under classic rock. Still, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers were dear to me. An older sister made me a fan, and the songs lived marrow-deep in my bones. When the band announced a run at the Fillmore, I pledged to go.

With Petty as host, the Fillmore show attendees were treated to a tour of American roots music, psychedelia, foundational rock ’n’ roll, and Heartbreakers’ hits and obscurities, plus guest appearances by Roger McGuinn, Carl Perks, and John Lee Hooker.

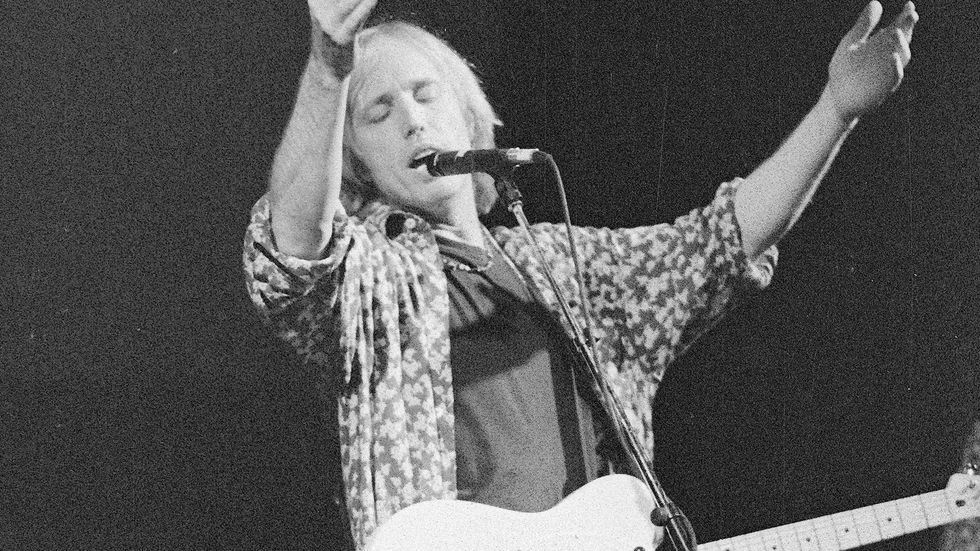

Photo by Steve Minor

Tickets disappeared fast, but my sister scored a few for a show early on in the run, and when the day came, we set up camp on Geary Boulevard sometime around mid-morning in hopes of a shot at the front row. We weren’t alone. Our day in line was hilarious in a beautiful, old San Francisco kind of way, which is to say full of randomness, bacchanalia, and various brands of benevolent psychosis. The new friends we met were capital “C” characters. The air was fragrant. And for several hours we partied together, ate fried chicken and mashed potatoes from the KFC down the block, traded concert stories, and talked about record collections. Standing in line, I noticed something else. If you could be bothered to be at the Fillmore preposterously early and spend hours of your life sitting on cold concrete at great risk of terrible disappointment, you had a shot at the 10-20 tickets the Fillmore kept in reserve. I took note, and thought that if the show was good I might give it a try another day.

I guess I wouldn’t be writing this now if that first show wasn’t pure joy. We did make it up to the front—well the second row, anyway. And for a few hours I stood right there at Tom and Mike Campbell’s feet. I had expected a special show, and that I would have a blast. But I went home that night buzzing. I felt the same the next day. And by the time the 20-show run was done, I’d seen four of them.

“Our day in line was hilarious in a beautiful, old San Francisco kind of way, which is to say full of randomness, bacchanalia, and various brands of benevolent psychosis.”

There is an inexplicable warmth and magic about the Fillmore. There are grander and prettier venues in the world. But few are as rich with ghosts and aura. It may look like a simple old dance hall, but the grand chandeliers, psychedelic posters, and red velvet always lend a sense of sanctuary. And when you imagine the figures that stood on that stage, and feel the weight of that history, it feels even more enveloping and spiritual. Up on stage, the Heartbreaker’s mountain of old equipment seemed at home amid the Fillmore’s gold and crimson glow. Tom and Mike’s blonde Fender Bassmans looked dusty and earthy. And if you squinted, the scene looked a little like the barn shot on the back of Neil Young’s Harvest recreated in a Victorian bordello.

One of the Heartbreaker’s motivations for the Fillmore was a desire to shed their showbiz sheen for a minute. Certainly, the Heartbreakers machine had taken on a kind of predictability in the years leading up to the Fillmore run. But whether they considered it or not, the Heartbreakers were also taking part in a great tradition of cultural dynamism and exchange—dating back decades to the migrations of the Byrds, CSNY, and, in a way, the Beats before them—that of shaking off the shackles and glitter fix of Hollywood and heading to the North Country to get loose. Not coincidentally, the atmosphere around the Fillmore shows had the uncanny feel of a Grateful Dead show. The environment was intensely positive and contagious, and the Fillmore hummed with the energy of a fantastic party, well before the Heartbreakers even took the stage.

The exterior of the Fillmore, with Geary Boulevard in front.

Photo courtesy of Wiki Commons

At each of the four shows I attended (each spent rapt, leaning on the stage at the feet of Mike Campbell), the band kicked off with a three-punch flurry of Chuck Berry’s “Around and Around” (in the fashion of the Stones version), the 1987 nugget “Jammin’ Me,” and “Runnin’ Down a Dream,” which was traditionally a set closer. It takes a very confident band, sitting on a mighty cache of tunes, to come out swinging that hard. And as the band got cooking over the course of those first three tunes, you felt a giddy momentum and sense of movement gather in the crowd. From there, each show took its own shape, and on most nights the sense of anticipation and surprise pivoted around the set switch-ups and the covers the band threw in so effortlessly: JJ Cale’s “Call Me the Breeze and “Crazy Mama,” Mike Campbell taking solo turns on Ventures tunes and the Goldfinger theme, a beautiful, moody take on Bill Withers’ “Ain’t No Sunshine,” the Zombies electric 12-string lament “I Want You Back Again,” and, in a nod to the creative conduit between L.A. and the Bay, the Grateful Dead’s “Friend of the Devil”

“The Fillmore hummed with the energy of a fantastic party, well before the Heartbreakers even took the stage.”

Then there were the guests. Roger McGuinn grinning as the band of assassins behind him summoned the amphetamine drive of “Eight Miles High” once again. Carl Perkins grinning even wider and devilishly, in real blue suede shoes, as he dazzled Campbell with his own very underrated and deadly picking. Guest turns can feel terribly contrived on big stages—just another showbiz move to get a few wows. But like so many other little moments at the Fillmore, these were peppered with spontaneity. I distinctly remember Mike Campbell laughingly waving away the clouds of pot smoke as Perkins, a classy gent and one of rock ‘n’ roll’s elder statesman, took the stage. And at one point during the McGuinn guest set, Campbell took the black Squier Telecaster he’d just used for “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” and gifted it to one of the regulars from the line out on Geary. She hadn’t yet missed a show, another front-row lunatic told me. I suspect he hadn’t missed many himself.

If I am honest, when I listen to the Fillmore performances as they appear on the new release, they seem much smoother and more polished than anything I remember hearing on those four nights. Up in the front row, I was taking more than a little heat from Campbell’s Bassman and Kustom amps, not to mention a whole lot of drums and cymbal splash. It all sounded so incredibly raw and rambunctious. So, I can’t help but think about how cool it would be to have a go at that mix—to coax all the rowdy grit I heard from this weird Southern hippie amalgam of the Stones, Byrds, and Dead turned into a monster tavern cover band that growled, roared, laughed, and drove 1,300 souls to beaming happiness for 20 nights. Maybe I’m wrong, but I have a feeling my old buddies from that line outside the Fillmore would really love it.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.