The last few years have been life-changing for Jason Isbell. Since departing the seminal Southern rock outfit Drive-By Truckers nearly a decade ago, Isbell created a quintet of studio albums, got sober, married singer/songwriter Amanda Shires, and is expecting a daughter. And since releasing his breakthrough album, Southeastern, in June 2013, he’s become a critical darling of the Americana scene.

Southeastern is a heavy album. Isbell tackles topics that could be uncomfortable in the hands of a lesser wordsmith. He captures the essence of Southern culture without playing into stereotypical traps that fuel today’s lowest-common-denominator country hits. Imagine Faulkner ghostwriting for the Band, with everything passing through John Prine.

But there’s another side to Isbell. His wit and humor are boundless, as demonstrated by his immensely quotable Twitter feed. “You can name a baby Klon Centaur. Boy or girl. I checked,” he tweeted shortly after finding out that he and his wife were expecting. When asked how Klon was doing in the baby name race, Isbell replied “Not too well, especially since we’re having a girl. That might have worked if we were having a boy. The good news is that my wife is actually picking up a Klon Centaur today. That will have to do.”

For his Southeastern follow-up—the just-released Something More Than Free—Isbell gave his band, the 400 Unit, greater freedom and more input on the final product. He also brought back Southeastern producer Dave Cobb. The results range from a stripped-down depiction of requited love (“Flagship”), soulful swamp rock (“Palmetto Rose”), and a heartfelt ode to the breakup of a favorite band, Centro-matic (“To a Band That I Loved”). “I feel like I’m doing the type of music that John Prine made, or Kristofferson, or even the Stones,” he says. “It’s all folk music, really. And it’s all rock 'n' roll at the same time.”

Sometimes Isbell is the “token Americana act” at big festivals, but the label could be worse. “It’s a better category to be in than country nowadays,” he says. “When people hear ‘country,’ they think of what’s on the radio. A lot of great musicians and songwriters have found their way into the Americana community. It’s gotta be called something, I guess, and that’s about the best you could hope for.” We spoke with Isbell about his writing process, new pedal discoveries, and the secret to breaking in a new flattop.

Do you need an album project to focus on writing, or are the creative wheels always turning?

It’s pretty constant—I write year-round. I do more work when I have studio time scheduled, or when I’m writing for a certain record. But I take a lot of notes and write whether I’m working on a record or not.

low end in the right way.”

There’s more of a band feel to the new album, and it’s a bit happier than Southeastern.

Yeah, maybe so. I’m in a better place personally. When I wrote Southeastern, I was still getting used to the world as a sober person and to a new relationship. Things were great, but they were up and down. And there’s a lot more band participation on this album. That’s probably due to the fact that while touring behind Southeastern, we developed a good way to work. The live show now is not just a band coming out to play a couple hours of songs. Band members come and go. I do some songs on solo acoustic, but in the last minute the band comes in and gradually builds the song. Things like that put a working relationship in a new light, and we put a lot of that energy and focus into making this new record. I really like having a band behind me, and I wanted to use these guys as much as I could while still serving the songs.

Do you do much pre-production with the producer?

No. Nobody hears the songs before I get up and play them right before we record them. I play a song, and then we all sit down at our stations and start playing.

So you try to capture the players’ immediate reaction to a song?

Right. Sometimes you get the best takes when people aren’t too familiar with the material. I’ve got really good players in my band and the luxury of not having to record albums too quickly. I don’t enjoy spending more than a month in the studio—I probably won’t ever do that. Still, three weeks to a month at a studio like the Sound Emporium in Nashville can be more expensive than some bands can afford, so they have to work up those songs in advance, make demos, discuss them, and then go in and knock it out. Luckily, we’re at a point now where we can take our time and work on arrangements one at a time. We don’t take home rough mixes at the end of the night. We leave it all in the studio, go home and sleep, and come back. Otherwise you fall in love with a mix, or a level, or a tone that might not turn out to be the best thing for the record.

How important is the first line of a song? And does it usually come first?

It happens all different ways for me. The first line is incredibly important. It’s like a novel: If your first line’s not working, then nobody’s going to listen to the second one. I don’t always write that first. Usually I start with a chorus or a verse, and in the editing process things get moved around a lot.

Some bands need to let a song develop over a tour before being comfortable enough to commit it to a record.

Yeah, a lot of bands are that way, but I’m not doing this to feel comfortable. That’s the opposite of why I do it.

Did any songs take surprising turns in the studio?

Yeah. We recorded this song called “Speed Trap Town” with the full band. About a week later I realized it wasn’t working. The lyric was very personal—dark in a lot of ways. There was longing in there, and the rocked-out arrangement just didn’t seem right. I’ve got this Martin ’56 D-18 that’s all over Southeastern and this record too. It’s my go-to in the studio—I use it on just about every acoustic guitar song. I sat down and redid the song in one take. Then I went back and put a slide guitar part on top. I’ve got an old Gretsch that I played through a Dumble with the SlideRig compressor, which is like an 1176. And that was it, pretty much. When I heard it more sparse and simple it just made a lot more sense.

“24 Frames” has almost a retro ’90s vibe. Was that something you had in mind going in?

Yeah, we talked about that a bit in the studio. It wasn’t conscious until we all heard the song and felt like that was a good direction. We talked about some R.E.M. records, things that we were all infatuated with in those days.

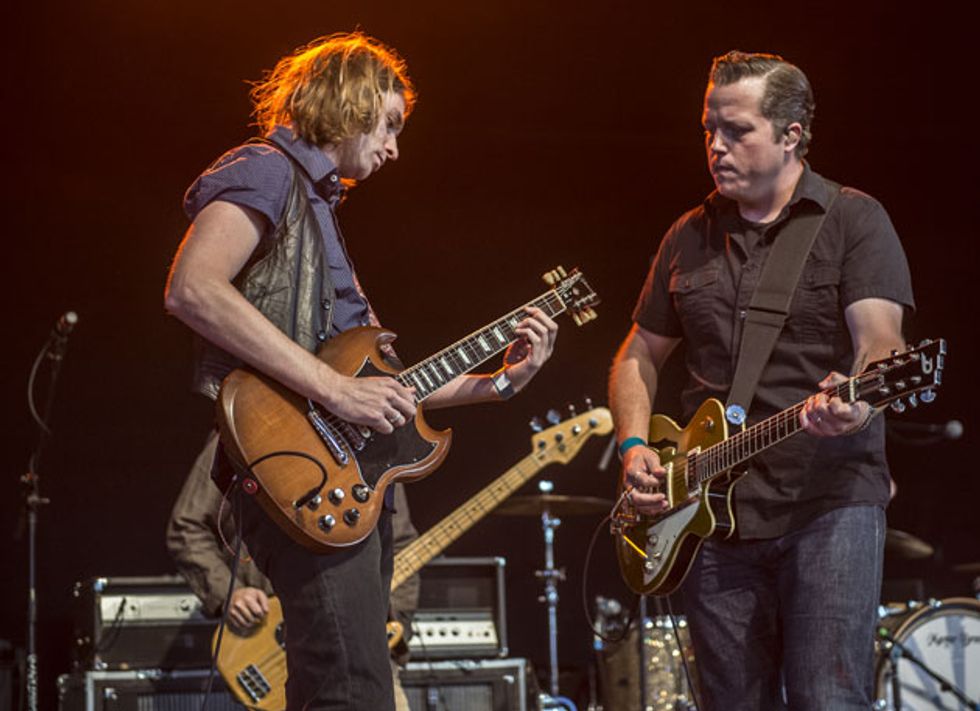

The twin-guitar attack of Isbell and Sadler Vaden comes to life on the new album. “For the most part, it just came through naturally,” says Isbell. Photo by Brian Glass

How big an influence was R.E.M.?

They were huge, man. When I was in the Truckers I spent some time with those guys. That was a really big deal to me. Pete [Buck] would let me borrow guitars when we were in the studio. I got to sing karaoke with [Mike] Mills and have beers with him, stuff like that. That band is a really big deal to me. They made beautiful music for a long time.

You grew up in North Alabama, not far from the Muscle Shoals scene. How does that influence manifest in your songs?

“Palmetto Rose” is a good one for that. It has a bit more of a backbeat than some of the others. There’s a lot of Rolling Stones in that song. Chad [Gamble, drummer] and Jimbo [Hart, bassist] are from Muscle Shoals also, and just about everything we do has that flavor just because of how those guys play. They have such a loose groove, where the tempo stays put, and they sit right on the back edge of it. It’s such a beautiful thing.

You play a little Merle Travis-style solo on “How to Forget.” Was Merle one of your guys growing up?

Oh yeah. I’m not great at that style. It’s a lot like playing the piano because you have to really get your thumb to do a certain type of muscle memory. I wouldn’t say I’m that type of player, but I can do just enough to augment the songs I write. My uncle and granddad were big Chet Atkins fans, so I grew up listening to a lot of Chet. I saw him in concert as a kid with Steve Wariner opening. It was amazing.

Jason Isbell's Gear

Guitars

Martin D-18 Authentic 1939

Martin Custom D-35

Martin HD-28E Retro

Fender Custom Shop 1960 Relic Telecaster Custom

Gibson Collector’s Choice #12 1957 Les Paul Goldtop

Duesenberg Fullerton Elite

Duesenberg Starplayer TV

Amps

Sommatone Roaring 40 Head with 2x12 cab

Magnatone Super 59 Head with 2x12 cab

Effects

AnalogMan Sun Lion

Klon Centaur (silver, no horsie)

Origin Effects SlideRig Compact Deluxe (x2)

Greer Amps Lightspeed

J. Rockett Blue Note

Electro-Harmonix Micro POG

Strymon Flint

Strymon Deco

Wampler Faux Tape Echo

Wampler Faux Spring Reverb

Fishman Aura Spectrum DI (x2)

Selah Effects Quartz Timer

Mission Engineering Expression Pedal

Mission Engineering Expressionator

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

Ernie Ball Regular Slinky (.010-.046)

Martin SP Medium (.013-.056)

Dunlop Tortex 1.14 mm picks

Elliot and G7th capos

RJM Mastermind GT/22

RJM Effect Gizmo

RJM Mini Effect Gizmo

Your tone on that track is very organic.

That solo was Dave’s ’59 Gretsch Jet Firebird with the quiet Filter’Tron pickups through a Fulltone Tape Echo and probably an old Ampeg Rocket from the ’60s.

The solo to “Children of Children” is ethereal and moving. How did you get that singing tone?

That was the Dumble for sure. I also used the Dusenberg Starplayer and the Origin Effects Slide Rig compressor. That compressor is really, really cool. It took me a while to get it transparent enough. That word is used way too much in the effects world, but with a compressor it makes sense. I didn’t want it to seem like too much of an effect. I just wanted to have a lot of sustain. I didn’t take long on that solo, maybe two or three takes.

Which guitars do you take on the road?

I’ve got a double-bound Masterbuilt Tele that Paul Waller built. There’s a Gibson Collector’s Choice #12 goldtop that I put some non-potted pickups in. I haven’t had a Les Paul in years. I played one with the Truckers quite a bit, but it got stolen and I could never find one I liked enough to replace it. That goldtop is just a great guitar, especially if you put in pickups without the wax, so you can get that real sparkly top end that PAFs had.

I’ve seen you play Duesenbergs quite a bit.

I have two Duesenbergs: a Starplayer TV goldtop and a Fullerton Elite. Both are really great. The Starplayer was my No. 1 for many years—I’ve got two identical ones. Those guitars stay in tune really, really well. I like how those pickups sound. The middle position on the Fullerton is really cool, because it’s essentially got a P-90 in the neck and a humbucker in the bridge. Of course, Duesenberg makes all their own stuff, so they’re not exactly like other pickups.

How about acoustics?

I’ve got a couple of Martins. My backup acoustic is an HD-28 Retro, and I’ve got a pretty new D-18 Authentic 1939. Martin gave me that for my birthday—it’s unreal! They built me a D-35 I helped design about a year and a half ago. That’s a great guitar, but that D-18—I don’t know if it’s something about the mahogany, or what. It’s super light and super loud. It uses hide glue, and the bracing is done in the old, pre-war way. It’s really great.

Isbell’s No. 1 on the road is a stock Duesenberg Starplayer TV, as heard on the “Children of Children” solo.

Photo by Brian Glass

I heard that you use Outkast’s music to break in your acoustics.

Yeah, I do that when I get a new acoustic. Sometimes I set them on a kitchen table and balance an EBow over the soundhole and let it ring out until the battery dies. You know, just to open them up a bit.

Why does Outkast’s music works best? Is it a Southern thing, or did you go through Wu-Tang, N.W.A, and Mobb Deep first?

I just love Outkast. It’s nicer for me to come home and have Outkast playing than just about anything else. But I did need music with a lot of bass. Nowadays, it’s funny how the 808 [Roland drum machine] is used. On a lot of these Rick Ross singles, the rumble goes on for eight bars. I guess they’re trying to get a solid trunk rattle from ten seconds of music. I can’t stand that. I really like when the 808 is used like a kick drum rather than a Moog Phatty or something. It bothers me physically—it makes me dizzy. Outkast is probably the last hip-hop group that used low end in the right way.

The guitar needs to dance a bit.

Yeah. You just want to shake it around and get everything that’s going to fall into the cracks in there as soon as possible.

I saw your post on Instagram of your new pedalboard.

My tech just finished up a big switching-style rig that I just started using this week, and it’s changed my life. It’s made everything so much easier. Being able to hit one button and control three or four pedals at once just saves me so much anxiety.

YouTube It

Isbell and the 400 Unit take on “24 Frames” with excellent 12-string slide work by Sadler Vaden.

What are some of your recent pedal discoveries?

I’ve had this Analog Man Sun Lion that Marc Ford gave me a decade ago. Recently, I had some repairs done and discovered that it’s No. 3. The Beano boost on that pedal is incredible. It reacts really well to an already hot tube amp. I like the J. Rockett Blue Note—that’s a good drive. I did a comparison with the Archer and the KTR Klon, and the Blue Note won out, to my ears. Actually, my wife is picking me up an original Klon Centaur today. They got one in at Carter Vintage in Nashville, my local shop. That’s going to be exciting.

You brought back Dave Cobb to produce. What made you want to work with him again?

He’s got a Dumble—that’s the only reason! [Laughs.] No, but it doesn’t hurt. He comes up with good ideas that help the arrangements, and he does that without being domineering. In my experience, if a producer is really talented, it can be hell trying to be in the studio with them for two or three weeks. They’re set in their ways, and you end up with records that have that “signature” sound. I think that’s a problem, honestly. If you hear something and can automatically say which producer made that record, that’s too much of a footprint. What you’re listening to should sound like the best example of the artist. I love Nigel Godrich—he does great work. I like T Bone Burnett’s work sometimes, though it’s a little infuriating to me when I’m listening to what sounds like a T Bone Burnett record when that’s not what I bought at the record store. Dave’s really good about bringing out the best in individual artists without making it sound like a Dave Cobb record, and he can do it without driving everyone crazy. That was a no-brainer this time around.

So is Dave letting you take the Dumble out on the road?

He would if I asked him, but my road rig is pretty much set. His Dumble is low wattage and build into a Fender blackface Deluxe enclosure. Alexander [Dumble] just took the guts out and put his stuff in there. It wouldn’t really work for me in a live setting. And you know, what would Dave use in the studio? He has a lot of amps, but he uses that sucker a lot. He might lose work. [Laughs.]

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)