It’s not uncommon for a guitarist to become steeped in a particular era or genre. But it’s rare that a player pulls off a signature approach in doing so. JD McPherson, with his deep knowledge of 1950s and ’60s rock and R&B, is just the sort of exceptional musician who makes something new from old materials.

McPherson, who turns 38 this month, grew up in Oklahoma on a cattle ranch. He took up the guitar at 13 and essentially worked backwards, starting off in punk bands and learning about early rock by checking out the musicians who inspired such groups as the Clash. Though a formidable guitarist by his late teens, McPherson studied film as an undergraduate and open media as a graduate student. While he focused on video-art installations, he devoured obscured 1950s sides and played guitar in his downtime.

After school, McPherson took a job in the art department at a middle school in Tulsa, but was fired from that post when the school’s administration took exception to his avant-garde tendencies. He also played in the Tulsa-based rockabilly group the Starkweather Boys, catching the attention of Jimmy Sutton, a Chicago bassist, record label owner, and producer. This led to a gig playing with Sutton, who eventually produced and released McPherson’s strong first solo album, 2010’s Signs & Signifiers (re-released on Rounder in 2012).

Following a 2014 EP, The Warm Covers, McPherson released his sophomore full-length album, Let the Good Times Roll. This time McPherson teamed up with producer Mark Neill, who’s known for his work with the Black Keys. With Sutton on acoustic and electric basses, Jason Smay on drums, Raynier Jacob Jacildo on piano and organ, and Doug Corcoran on saxophone and miscellaneous instruments, McPherson has created an album that’s a lexicon of vintage rock grooves and timbres, and an incredibly fun listen.

McPherson told us about his antecedents and his fondness for Partscasters and boutique pedals, as well as working in the time machine that is Neill’s studio.

Describe your formative musical experiences.

The very earliest musical experience was when my sister put a Walkman on my ears and played “The Reflex” by Duran Duran. I remember it was like having candy in my ears because at that point, I’d only listened to what my parents played in the car. I had much older brothers who were musicians, and when I first became a really active listener, they turned me on to guitar-oriented music of the ’60s and ’70s: Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix, and the Allman Brothers. That of course got me wanting to play the guitar. My oldest brother told me, “If you can play ‘Stairway to Heaven,’ you can play anything.” And that’s how it all began.

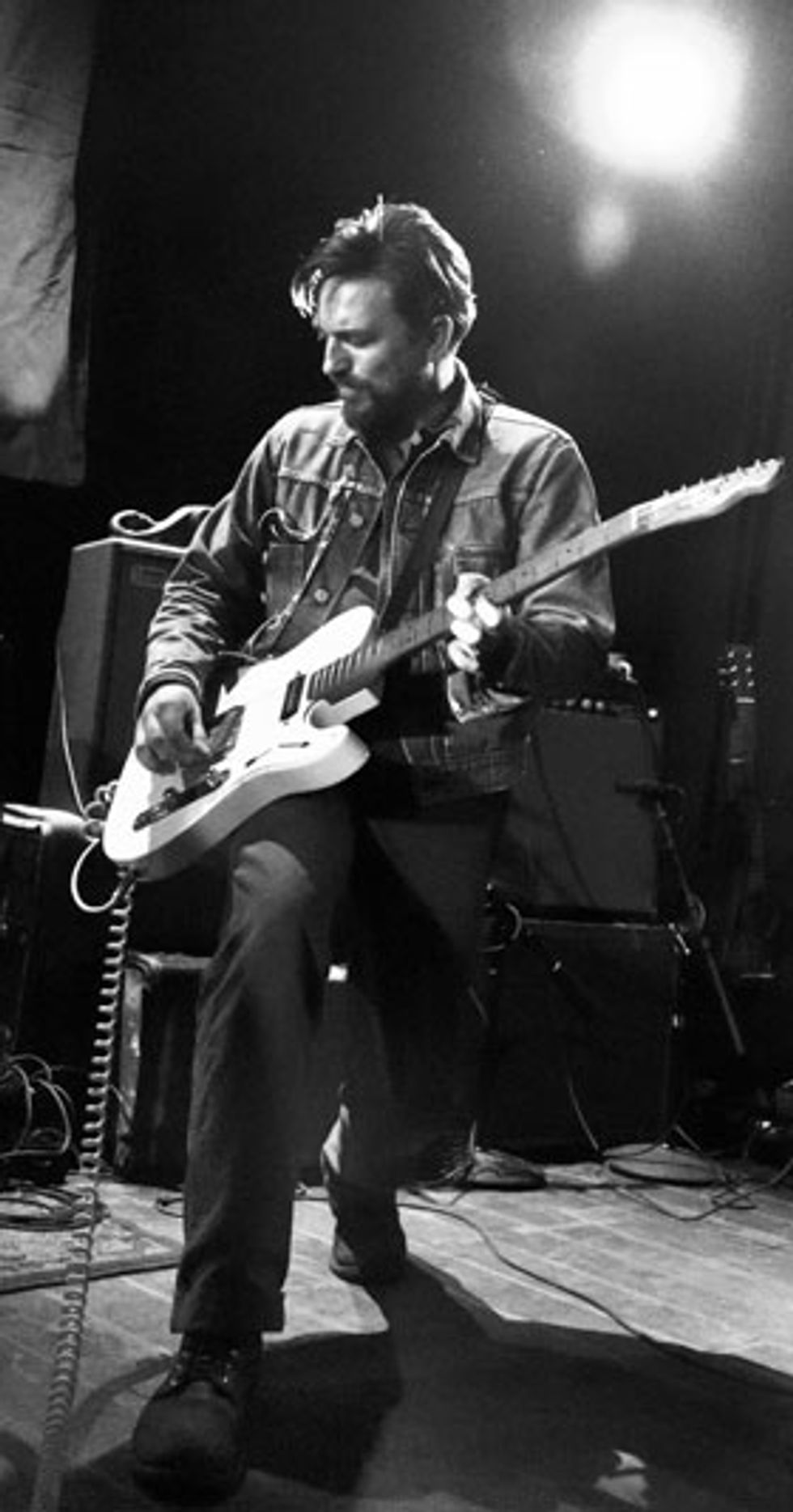

“I can’t live without tremolo and delay,” says McPherson. Photo by Sarah Hess.

When I was a teenager I got into punk rock, which my brothers weren’t at all interested in, and everything that springs off into punk. For example, take London Calling by the Clash. It might be categorized as punk, but it encompasses so many different categories—rockabilly, ska, rocksteady. It really opened a lot of doors for me. My dad is really into Delta blues and jazz, so that rubbed off on me, too.

When did you first get immersed in the 1950s rock that’s such a big influence on your sound?

I was probably 17. Of course I’d heard the music before that, but it didn’t really click with me until I listened to it carefully. I got really into songs like “Midnight Shift” and “Love Me” with Sonny Curtis on guitar—such a great player. I found 1950s rock at just the right time in my life. It was energetic and fun music for teenagers, but it also had great finesse and musicality. At the same time it was raw and primal, with the immediacy of the punk rock that I was really into. In any case, once I got a hold of ’50s rock, I started playing songs like Buddy Holly’s “Rock Around with Ollie Vee” in my punk band.

How did you go about absorbing this music? Did you sit down with a record player and transcribe the tunes?

Figuring out Merle Travis picking on my own was a big thing. I also learned from videocassettes, which were not readily available like YouTube lessons are these days. My family and I used to go to a music store in Portsmouth, Arkansas, and there I found rockabilly VHS lessons by Jim Weider and Brian Setzer. I started with the Weider tape, which taught specific licks, like in the style of Cliff Gallup, and then I graduated to Setzer, where he’s doing totally nuts, acrobatic stuff.

I’ve always had a pretty good ear and have been able to pick things out for myself. The hardest thing I ever did was transcribe the head for Django Reinhardt’s “Minor Swing.” This was before there was slow-down software, which would have made things a whole lot easier!

Are you a jazz fan, and if so, how has it impacted your music?

Oh god, yeah, absolutely. Charlie Christian is one of the finest players in any style who ever lived—I really love that stuff. Although it doesn’t find its way into most of my music, jazz is definitely a strong influence. Having that vocabulary is really important in terms of fluidity on the guitar. Also, it’s interesting how jazz has filtered into blues and rock. T-Bone Walker listened to a lot of Django, and Chuck Berry listened to a lot of T-Bone, so it’s all very closely knit.

JD McPherson has a thing for Fender Telecasters, particularly Partscasters. “For about 10 years the only guitar I played was a butterscotch Tele body that had a C-shaped ’50s-style neck and even a Squier neck on it for a while when the other neck broke. I put a Bigsby on it, and a Vintage Vibe Charlie Christian pickup in the neck, as well as their blade pickup in the bridge. I turned the switch plate around and put a fast tone pot in it, so I could do tone bends, especially for

more country-influenced playing.” Photo by Mick Orlosky.

Who are some other guitarists in your pantheon?

Mickey Baker was one of the coolest guitar players ever. I really love listening to Bo Diddley. It’s almost like his thing is not about the guitar. He invented a new instrument and was so innovative in his approach, thinking about music on a multiplanar level: rhythmic and percussive as much as it is melodic, and the tremolo adds a whole other aspect. I’m a big fan of Johnny Marr from the Smiths; Reeves Gabrels, a very interesting guitarist who played with David Bowie for a while; and Grady Martin, who was probably the most important session player ever. And yesterday I stayed up just about all night watching every video online I could find of Nels Cline—amazing stuff.

I really love drummers and bassists, too, and I listen to them as much as guitar players. I love Keith Richards and Mick Taylor, but when I listen to the Rolling Stones, I really hone in on what Charlie Watts is doing. [Motown session bassist] James Jamerson is a huge influence as well.

The album has a feel that’s at once retro and modern.

In some ways it lives in the analog domain—we recorded a lot of the parts to tape—but there’s definitely no reason to not take advantage of any musical tool available to you. I’m pretty pragmatic: If it sounds good and it helps your music, then why not throw in some overdubs after you’ve done the main recording session?

What was it like to record with Mark Neill?

We recorded at his Soil of the South Studio, in Valdosta, Georgia. It’s like taking a trip back in time. The studio looks like someone found an abandoned building and opened it up to find a studio from the early ’60s. It doesn’t look at all hip, with its wood paneling and linoleum floors, but it’s definitely the coolest place I’ve ever recorded. Mark has so much great stuff in there—one of the congas that Louis Prima played on his Capitol recordings, every Neumann and RCA mic you can imagine, two big German plate reverbs … essentially any tool you need to make a new record sound as if it were made in 1965 or earlier. Plus Mark has the huge knowledge base needed to do the job. He studied with geniuses like Owen Bradley [one of the biggest producers in Nashville during the 1950s and ’60s]. So recording with Mark is, in a way, like making a record with Owen Bradley.

How’d you get such great guitar sounds?

I played everything through a 1950s Magnatone, and mainly used a Fender Strat and a Rickenbacker. We also used a 1950s Gretsch drum kit—the same one heard on the Black Keys album Brothers. All are such good and versatile instruments, which offered me so many fresh tones.

JD McPherson's Gear

Guitars

Telecaster-style guitars from parts, including Vintage Vibe pickups and a Bigsby tailpiece

Fender Custom Shop 1950s-style Telecaster with TK Smith pickups

Fender Custom Shop 1950s-style Stratocaster with Curtis Novak pickups

Amps

Texotica Presidio 15

Effects

Dr. Scientist Reverberator

Danelectro Reel Echo

Fulltone Supa-Trem

Nocturne DynoBrain Preamp

Strings and Picks

Assorted D’Addario

InTune GrippX-XJJb Jumbo Jazz picks (.88 mm)

Which specific Strat and Rickenbacker?

It’s a really special Ric, a beautiful bird’s-eye maple 381 with a tremolo tailpiece—Mark’s main guitar that he uses all the time on records. The Strat was a repro of Eric Clapton’s Blackie—something Mark acquired for me just for the record. He bought it because it sounded amazing unplugged. I ended up using it for half the record because I loved it so much.

What are your personal guitars?

I’ve always been a big fan of Fender Telecasters, particularly Partscasters. For about 10 years the only guitar I played was a butterscotch Tele body that had a C-shaped ’50s-style neck and even a Squier neck on it for a while when the other neck broke. I put a Bigsby on it, and a Vintage Vibe Charlie Christian pickup in the neck, as well as their blade pickup in the bridge. I turned the switch plate around and put a fast tone pot in it, so I could do tone bends, especially for more country-influenced playing.

Recently Fender built me a ’50s-style Strat. I had Curtis Novak make me a custom pickguard with some drool-worthy pickups for it. They’re so hot and really sound incredible. And my No. 1 right now is a ’50s-style Tele. I had TK Smith, who’s a genius, make me pickups and a nice pickguard for the guitar. He’s out in the desert, in Joshua Tree, California, and he also makes his own instruments based on Paul Bigsby guitars of the 1950s—super artisanal electric guitars.

What about amps?

I run through my Texotica Presidio 15 made by Billy Horton, who’s got this great studio called Fort Horton, near Austin. A while back, Billy started making amps based on ’50s Tweeds. Mine’s like a Fender Pro, with a 15" speaker. I really love it. I’ve used it for four years, and it’s been like a tank.

And effects?

I recently fell in love with this company up in Canada called Dr. Scientist. When we recorded the record with Mark Neill, we used so much plate reverb, and I asked Mark if he knew of any pedal I could use live for emulating the plate. He flipped out and said that Dr. Scientist’s Reverberator is the best reverb pedal in the world, and I love it—it’s a fantastic-sounding pedal and so well built.

I have a couple of others. I can’t live without tremolo and delay. I use a Fulltone Supa-Trem and a Danelectro Reel Echo, which they don’t make anymore. And I’m interested in checking out Strymon’s El Capistan echo pedal, it looks really nice. At some point I got a Nocturne DynoBrain Preamp, and it just sat in my suitcase for a while. But after I finally plugged it in to see what it’s all about, I started using it all the time to add a little clean grit to my sound. It pairs so well with echo and reverb.

Photo by Mark Newsome Kartarik.

The album has such great arrangements. Did you write the parts, or was it more of a collective thing between you and your bandmates?

For many of the parts, I came up with the arrangements, although things of course changed organically in the studio as we were recording. For example, “Bridgebuilder” has this cool drum part that I’d had in my head for a long time. Making this record was kind of weird in that I didn’t share the music with anyone until we were in the studio—not even Mark heard any of it in advance. That was a tough sell.

Why didn’t you share the music in advance?

I was holding it close to my chest because I didn’t feel comfortable sharing music that was probably completely different from what my bandmates expected. The songs are pretty out there compared to the first record. The good part was that my band is so great. Those guys can pretty much nail whatever you ask them to do. They have such an organic approach and they really gave the songs the kind of urgency that they called for. And it made the music sound fresh to work up the songs in the studio, and then learn them to play live.

How’d you get that unusual sound on the intro to “Bossy,” almost like a mbira or thumb piano?

I played Mark’s 1960s Gibson B-25—it sounded like a million bucks—and a 1960s Gibson nylon-string as well. That intro is a composite of a few acoustic parts. We got every element down to tape, and then re-amped it all through the Magnatone.

“It Shook Me Up” has a great baritone solo.

That’s actually Mark Neill on his Danelectro 6-string electric bass. He’s not just an amazing producer but also an incredible player, and I really wanted to find a spotlight for him on the record.

“Mother of Lies” also has an excellent guitar solo, presumably yours. What’s your approach to soloing?

When recording a solo, I usually take a few passes. We recorded “Mother” live and the band kept playing until we found a groove. I got an idea, started the solo and kept building on it. On the record you can hear that there’s a bit of a slowdown after the solo. That wasn’t intentional, but since it was the best portion of the solo it made it to the record.

YouTube It

Watch JD McPherson and his band at an in-studio performance at Seattle’s KEXP.How do you find your own voice in channeling 1950s rock?

First and foremost, writing songs is the most important thing I do. I learned pretty early on that there might be some really cool stuff happening on a record, but if the songs don’t resonate on some level, then it doesn’t work. Being that my preference is for music from that time period, my songs are of course going to be evocative of that era. I love rock ’n’ roll so much—I’ve loved it for half of my life—and so it completely informs what I do.

Letting the Good Times Roll

In his own words, producer Mark Neill discusses recording JD McPherson’s new album.Before we made the record, JD and I talked for months. He would mention certain 1950s tracks, asking if I could identify which guitars were used, so that he could get the same sound. So I’d go dig out the records—I had all the 45s he mentioned—and almost every time it was a Stratocaster. A friend of mine had a ’57 reissue with an alder body that just has the most beautiful unplugged sound, and this solved the problem of how to get that old sound. We strung the guitar with semi-flat medium gauge strings, of course with a wound G, for a period-correct sound. We recorded the guitar electrically as well as acoustically, with a Neumann or SM57, since on those old Buddy Holly and Ritchie Valens tracks the vocal mic also captured the sound of the guitar.

The Magnatone amp we used is not actually a Magnatone. It’s got a 1951 Magnatone cabinet that I gutted and turned into a monster amp with a 6V6, 12A7 front end, and a JBL speaker. It delivers a wallop and is completely wild, barely stable enough to use as an amp. If your guitar has a scratchy pot when you play through it, it’s the loudest scratchy pot you’ve ever heard.

As for acoustics, we used a Gibson B-25, a weird little guitar that I write all my songs on. Everyone who comes to my studio loves to play it because it’s got a slender neck and low tension, and it’s a paradoxically loud guitar that can keep up with a Martin D-18. We also used my short-scale 1960s Gibson nylon-string and processed the corn out of it: I re-amped it out in the hallway of the studio. There’s something fascinating about applying a lot of overdrive to a guitar that doesn’t sustain a lot. I got this idea after seeing Willie Nelson’s touring rig and thinking, “Oh, that is so sick.”

I’ve never made a record like this before—it’s just not the way I do things. Most people think of it as very live-sounding, but it was constructed like a modern hip-hop record, with everything recorded in tiny bits and pieces. We started by recording just upright bass and kick drums and gradually worked out all the other layers. I used far more tracks on this album than any I’ve ever recorded. But it turned out to be a great record, and in the end that’s all that matters. —Mark Neill

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)