It’s not every day you get to speak with a bona fide rock ’n’ roll legend—especially one with an encyclopedic knowledge of tone, gear, and the mechanics of groove—but we interviewed Joe Perry and, man, he delivered in spades.

Perry, as you probably know, made his name in the ’70s with Aerosmith, and along with a few others—like Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, Jimi Hendrix, and people like that—defined the term “guitar hero.” (There’s a reason relative youngsters like, say, Slash, play Les Pauls and dress the way they do.) Perry’s playing is all over classic songs like “Dream On,” “Back in the Saddle,” “Sweet Emotion,” “Draw the Line,” and many, many others. But unlike other ’70s icons, Perry’s band, Aerosmith, had a second career in the ’80s and ’90s, which—at its peak—was even bigger than anything they’d done in their early years. Along the way, they also racked up multiple Grammy awards and a spot in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

You don’t build that type of stature without depth, and Perry’s got plenty of it. At 67, he remains a guitarist’s guitarist. He knows the tricks to coax classic sounds—some of which he invented—out of his rig. And he understands the quirks of guitars and the ways to get them to play and sound their best. But he also has an intimate, historical understanding of music making and songwriting. He knows about groove—and the subtle rhythmic mojo most players miss. And although he’s written timeless riffs (“Walk This Way,” anyone?), he knows when to make room for a vocal and how to showcase a lyric. Fifty-plus years of playing, performing, touring, and recording counts for something, and Perry still puts those lessons and experience into practice.

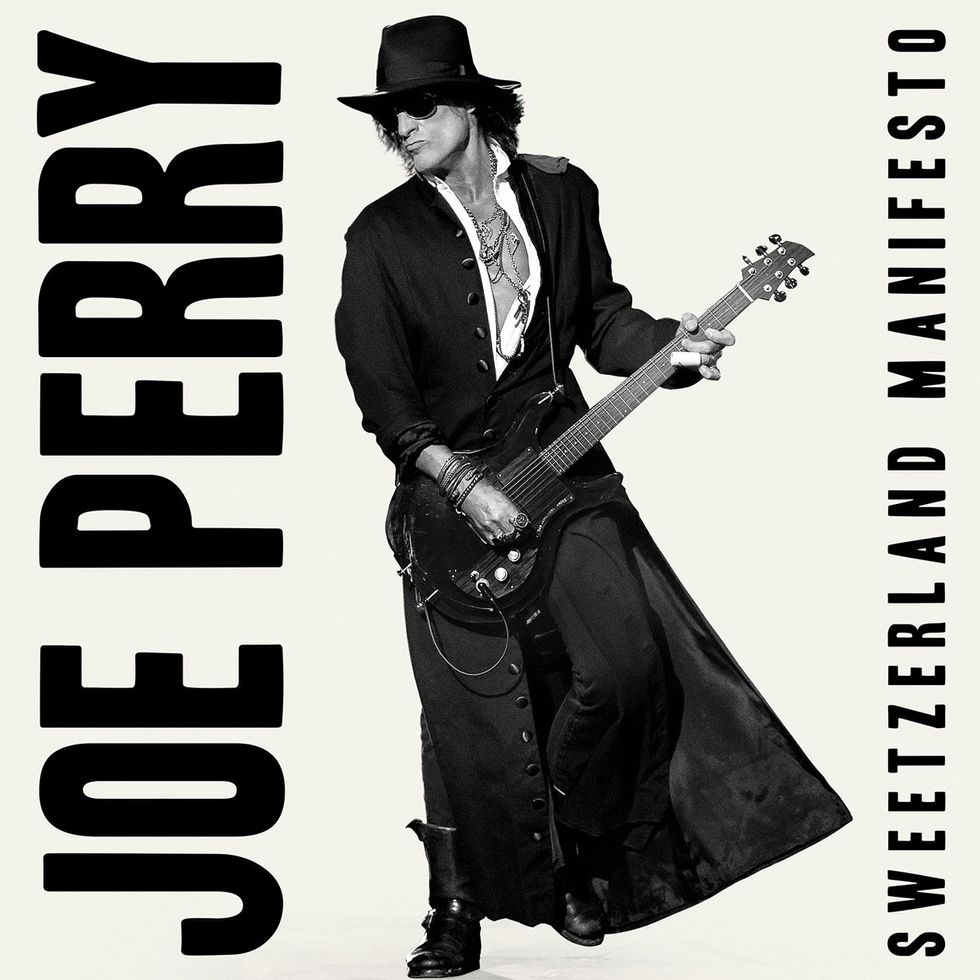

These days, in addition to his ongoing work with Aerosmith, whose classic lineup is still together, Perry is touring and recording with the Hollywood Vampires (a fun project that also includes Alice Cooper, Duff McKagan, and his close friend Johnny Depp), and has just released Sweetzerland Manifesto, his fourth solo album—not counting his three studio long-players with the Joe Perry Project, which he led from 1980 to 1983, during his hiatus from Aerosmith. Sweetzerland Manifesto, which was cut at Johnny Depp’s home studio in L.A., is classic Perry: swampy grooves, classic tones, funky tunings, and lots and lots of slide. The album also features guest vocals from Robin Zander (Cheap Trick), David Johansen (the New York Dolls), and Terry Reid (who, according to legend, was asked by Jimmy Page to front Led Zeppelin, but turned it down because he’d already committed to open for the Stones).

We spoke with Perry about everything. That includes slide playing, tunings, mastering rhythm and feel, discovering your ideal tone, tweaking guitars, the history of string gauges, and even how he’s managed to keep his hearing.

As an aside, we had a few scheduling challenges trying to arrange this interview. Eventually, my phone rang while I was standing in line at the supermarket. “Hello, this is Joe Perry,” an über-cool, gravely, Boston-twanged voice said in my ear.

“Hi Joe,” I said, shitting myself. “I’m in the supermarket. Can we reschedule this for another time?”

“Sure,” he said. “I’ll call you back in 15 minutes.”

Needless to say, my 16-year-old self stood in awe of the adult me—aside from the change of underwear, obviously.

You play a ton of slide on your new album. Let’s talk about that.

I probably picked it up seriously when I was about 18 or 19. I already had a pretty solid handle on the basics, and by that time—I was playing in a band by then—I’d seen plenty of guys do it. I’d managed to see a lot of guys come through Boston in the late ’60s. I saw everyone from Muddy Waters to Johnny Winter play slide. I got interested in different tunings and things like that, listening to the old blues guys. I just had a kind of natural feel for it. I’ve always had it as part of my repertoire, so to speak, of different ways to get sounds out of guitars.

Do you have preferred tunings that you use for slide?

Open G is the classic. I mean, Robert Johnson was probably the most famous of the old guys, but they all had different angles on their tunings. It’s one of those things you mainly just fiddle around with. But either open G or open A lends itself to a lot of different things. I also use open E. I use DADGAD—which is the tuning that Jimmy Page uses a lot—and then a lot of times I just play it in regular tuning.

Do you have a preferred guitar for slide?

When I’m with Aerosmith, I usually use a Supro Ozark 1560S. I have an old one and a reissue. My first one was a beginner’s model, a Danelectro, which I bought specifically for slide when I was 18 or 19. I have an old Rickenbacker lap steel, it’s a 1939, and I’ve played that on the road for years. I wrote the basic parts to “Rag Doll” on that. Probably the most recognizable song on the Ozark would be “Monkey on My Back.” [Editor’s note: from 1989’s Pump.] But I’ll find odd ones here and there that sound really good. Sometimes it’s a little cheap Supro, or Airline, or something like that, because those pickups sound great for slide. Sometimes, if I’m using a regular tuning, I just play slide on a Strat.

You use a lot of different tunings in general as well, even when not playing slide. Have you invented any or do you pretty much stick to those you mentioned?

There are a couple that I’ve changed—where I’ve tweaked some of those basic open chords. I don’t use as many as, say, Pagey. There are a few in my set of songs where those tunings form the base of the song, but I like to stick pretty much to either the open G, open A, and standard tuning. It just keeps it easier so you don’t have to have three or four guitars when you’re on the road. I try and limit it as much as I can because I know whatever I do in the studio, I’ll have to go out there and play live. I’ve been through that enough to know that if you saddle yourself with a particular guitar and with a particular tuning, you’ve got to bring it with you. I’d as soon keep it as limited as possible, so I’m not having to change guitars as much.

You are left-handed even though you play right-handed. Does that have any advantages? For example, have you stumbled on anything interesting that you wouldn’t have stumbled on otherwise?

I don’t know. I grew up in Hopedale [Massachusetts, a Boston suburb]. There were very few guitar players around and I wasn’t exposed to a lot of different kinds of music. I didn’t know there was a left-handed or right-handed way to play guitar. I took piano lessons for a while. I actually played clarinet for, like, three months. There were no left-handed pianos or left-handed clarinets that I know of.

I did try playing left-handed, just to see. It was just out of curiosity. I spent a couple of weeks trying and I thought it was a waste of time for me. So, I really couldn’t tell what the advantages would be. I’m sure there are people who say, “Your left hand or your right hand being a dominant hand on the neck gives you more dexterity.” I don’t know. It probably evens out, the pluses and minuses.

Can you talk about rhythm, feel, and how you approach groove? It seems to me that playing something like a shuffle is becoming a lost art.

I approach the rhythm as one of the most important elements. Even a ballad has a thing that can help create a mood and a bed for a melody, a lyric, and what the lyric is trying to get across. I mean certainly, the other end of it, the lyrics, are ultimately what people listen to—that and the melody—but most of the time, the songs that I write start with the rhythm. Once in a while, I’ll come up with a chord thing or a riff, but even then, the riff is built around that rhythm. I’ve steeped myself in that kind of music—whether it’s funk or disco or pop or whatever—and how the mechanics of that work. If you listen to Chuck Berry, that’s like a four-year college course in rhythm and how that works. There’s a feeling there you get when you interact with the bass and the drums. It’s really hard to capture. I’ve heard a lot of bad Chuck Berry imitators.

TIDBIT: Perry’s new solo album was recorded at Johnny Depp’s well-appointed home studio, which occupies a garage and the first floor of Depp’s house in Los Angeles, and sports top-of-the-line gear.

I have to say, the Stones are probably the closest cats to capturing that feel. They’ve studied it. They figured out how there’s a shuffle going on over a straight beat and getting that to work. I was fortunate enough to have Johnny Johnson, who played with Chuck Berry, down in the studio when we did [2004’s] Honkin' on Bobo. Watching him play, he had a swing and a feel, and along with Chuck’s rhythm, it just creates that boogie-woogie kind of shuffle. Then, obviously, you adapt that to what you’re going for. I mean, I think a lot of the newer bands don’t spend enough time paying attention and learning that. It’s not about scales and all that.

It takes a while to figure out why rhythm is so important—especially being in a band, in an ensemble situation—to what comes out. You may listen to the guitar player alone and that sounds okay, and the drummer alone, or the bass player, or the keyboard player—but they’ve all got to work together to make this feel, this drive, this very primal element that forms the bed of the song. The main thing goes back to when Dick Clark had his show and they would rate all the new songs by, “Can you dance to it?” That was it: Can you dance to it or not? That says so much about what music is for people. Electronic music, the DJs, it’s all about that: the beat. You get guys driving by in their cars and listening to rap and the bass is just thumping, man. That’s the hook in a lot of ways. There’s everything else—the ear candy that makes you love the song—but you’ve got to have that rhythm. That’s what I form everything around.

But it took me a while to figure that out. You can go out there and bang on chords like any other bunch of white kids in the suburbs in a garage, but to really get it, you’ve got to work it. I think what happened is, the guys that were playing the first rock ’n’ roll were jazz guys. They came up through jazz. They hear music—the rhythm—in a different way. When they play something simple like straight-ahead rock ’n’ roll, they bring something to the party. If you just, say, learned how to play drums from Van Halen, you’re not going to get that same feel. Again, look at the Stones. Charlie loves swing music and jazz. He comes out of that era. So did Bill Wyman. Keith plays rhythm. He’s got that right hand that just nails it. He is the best rhythm guitar player out there. He’s written countless songs that have that feel.

It goes back to what music was originally used for: It was the fire people danced around. There is a very intense sexual element to it. That’s the rhythm, the rhythm of life. If you follow music back, over the centuries, to where the roots of it are, it’s around the rhythm. It was about getting people to hang out together. It’s a mating dance, it’s…. Anyway, these are all general statements. But as an amateur musicologist, I’m following that path, paddling down that river, checking every inlet.

Perry in his guitar-hero glory onstage with Aerosmith, picking a low string on one of his signature Gibson Les Paul tiger-stripe finish guitars. Until this decade, Perry played Stratocasters and Les Pauls in concert almost exclusively, but has found additional inspiration in Echopark and TV Jones models. Photo by Jordi Vidal

You use TV Jones and Echopark guitars a lot on this album. What do those instruments offer that you can’t get from your Fenders and Gibsons?

Both guys [Editor’s note: That’s Gabriel Currie of Echopark and Thomas V. Jones of TV Jones.] have built guitars for me that are very close to perfect for what I want to use. Those guitars are basically made to my specs. I also have the Les Pauls and Strats. I’m really fond of a particular Strat that I put together about 20 years ago. It’s a left-handed body and a left-handed Tele neck. I found that the tension and the way the heavy string has that long distance from the nut to the tuning peg makes it resonate in a different way than, say, a right-handed Strat. Also, the high string is a little tighter. But these are really minute things. It’s just that after a while, those are the little things you notice. But a lot of times on the record, I just grabbed whatever was at hand. I’ll just choose one and then tweak the amp a little bit. A lot of it is just how you play. It’s in your fingers.

At the end of the day, you’re the one who’s playing it.

Yeah. I remember once, near the end of the ’70s—Ted Nugent was there and Eddie Van Halen had already made a name for himself—and Ted said to Ed, “You know, if I had the same rig and the same guitars as you did, I could sound like you.” Well, he put the guitar on and he sounded like Ted Nugent. So much of it is in your hands. I’ve seen Jeff Beck play—and he’s got his favorite guitars—but I’ve seen him pick up any old guitar, and after like two minutes you’d think he’d been playing that guitar for 10 years. So much of it is in your hands, especially when you’re chasing tone. A tendency now with a lot of players is to play with really distorted amps and to turn the gain way up—and there are a thousand different kinds of fuzz tones you can use for that—but I gotta say, I think my favorite tone is with everything turned up and you just get a nice clean ringing, chiming tone. Then, if you want to get it a little funky, you can maybe just turn the amp up a touch, put a little bit of drive on it, and get that sustain. You can go and go, all the way to the end to where it’s freaking out, but my standard tone—the rig that I use when I tour with my solo band or with Aerosmith—is a relatively clean tone and then I’ll build on top of that by using different guitars. For example, rather than using a Strat, I’ll use a humbucker, because it has a little more drive and you can get a little more of that crunch. Anyway, I like to hear the tone of the guitar more than the tone of an overdriven amp.

Joe Perry’s Gear (for Sweetzerland Manifesto)

GuitarsEchopark Ghetto Bird Custom

Echopark Joe Perry Model

TV Jones Custom with T-Armond pickups

Gibson Joe Perry ’59 Les Paul

Various Fender Telecasters and Stratocasters, including his left-handed Strat with a Tele neck

Amps

Supro 1695T Black Magick

Various Marshalls

Effects

Klon Centaur

Electro-Harmonix POG

DigiTech Whammy

Strings, Picks, and Slides

Ernie Ball Skinny Top Heavy Bottom custom sets (.008–.048)

Dunlop Medium picks

Dunlop Joe Perry Boneyard slides

So, do you get your distortion with pedals or by pushing the amp a little bit more?

It’s usually pushing the amp a little. They do have gain pedals that don’t color the sound at all. They just give it that little more—like another couple of dB push—and that’s usually enough if you want the thing to sing a little bit more. That’s why on the solo record there are so many different sounds, but it’s not like I used that many different guitars on it. It’s more about tweaking the amp a little bit and maybe playing a little bit harder, pushing it. Sometimes I play without a pick and that can help with the tone. Then there are other things where I want a little more attack and I'll use the pick. I’ve found that most of it comes from your hands. Then you get the base settings on your amp and pick a guitar that’s going to give you what you want. And I want to be able to hear the tone of that guitar as much as I can.

You do use a Klon Centaur though. Is that just to push it a little more?

It’s a pretty versatile pedal. The cat that makes them lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts, actually, and Brad [Whitford] and I were fortunate to get some of the first ones he made. That’s probably the one piece of equipment, besides a guitar, that I always bring. If somebody asks me to play on a record or go to a studio that I’ve never been to—if I don’t have an amp and I’ll use one of theirs—if I have a Klon, I know I can get the amp to sound the way I want. It’s not quite like a classic fuzz tone. It’s not just a straight drive. It’s kind of in-between. You can sculpt a good sound out of whatever you have. If somebody asks me to jam onstage, if I can get my hands on my Klon, it’s good.

What did you do before the Klons came out?

There were other pedals that were close. There are a lot of really good pedals. It’s just a matter of taste. But for me, the Klon works.

Are you particular about strings and picks?

The classic guitars that everybody goes crazy for—all those guitars made in the ’50s and ’40s—were made to play with heavier-gauge strings.

And flatwound, too.

And flatwound. And one of the things in the ’60s was that a lot of the English cats who were really studying the blues players were like, “How do they get those huge bends? How are they doing that?” Then you find out this guitar player would substitute his G string with a .010 so he could bend all over the place. So, they were pretty much the first ones to start using really light strings. They would take a banjo string, throw away the low E string, move the whole set down one, and then add a banjo string for the high E. I did that for about a year until Ernie Ball came out with a set, the Super Slinky, and then Rotosound, the English company, came out with sets of really light strings.

Putting super light strings on a Strat and getting it to stay in tune is a bitch. It takes a while to get that adjusted, but once you get it, it works. I’ve found that what you give up in tone—because with the smaller string gauge, there’s less metal to vibrate—you can make that up having the right guitar and amp setup. For me, it’s less wear and tear on my hands. I used to use .010s, then went to .009s, and for the last two years I started using .008s. I like it a lot because I can get bends on the low strings and it makes it a lot more fluid for me. I got a bit of arthritis in my hands and since I switched to .008s it seems to have abated a bit. But any time flesh touches metal, wear-and-tear is inevitable.

Along those lines, are there things you do to protect your hearing as well?

I don't play that loud [laughs]. Actually, I’ve definitely lost some top end, but I don’t use those ear things.

You use wedges?

I use wedges. The main thing is that I like to hear the band. The band should sound good onstage and the balance should sound good. You don’t want one guy playing screaming loud and another guy playing through a tiny amp. The main thing is to get a good balance right across the board. It makes it easier for the soundman and it makes it easier for everybody. There are a dozen sweet spots on the stage where I can stand and hear everybody without even having to rely on wedges.

I’ve been lucky to not have more hearing loss. But hey, I worked for 30 years to get a band that sounds great. But mainly, I want to hear the audience and hear how they’re reacting. A lot of people will feed the audience into those ear things, but it’s still unnatural to me. I just want to hear the real thing. It’s a balance.

YouTube It

“Train Kept A-Rollin’,” a staple of Aerosmith’s live sets for decades, gets an update by Perry with his pals Slash, Johnny Depp, and Dean DeLeo joining on guitar at L.A.’s the Roxy on January 16, 2018. The tune was first cut by R&B bandleader Tiny Bradshaw in 1951, but Perry’s multiple solos—summoned from his lefty Strat with a lefty Tele neck—are squarely in the moment.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)