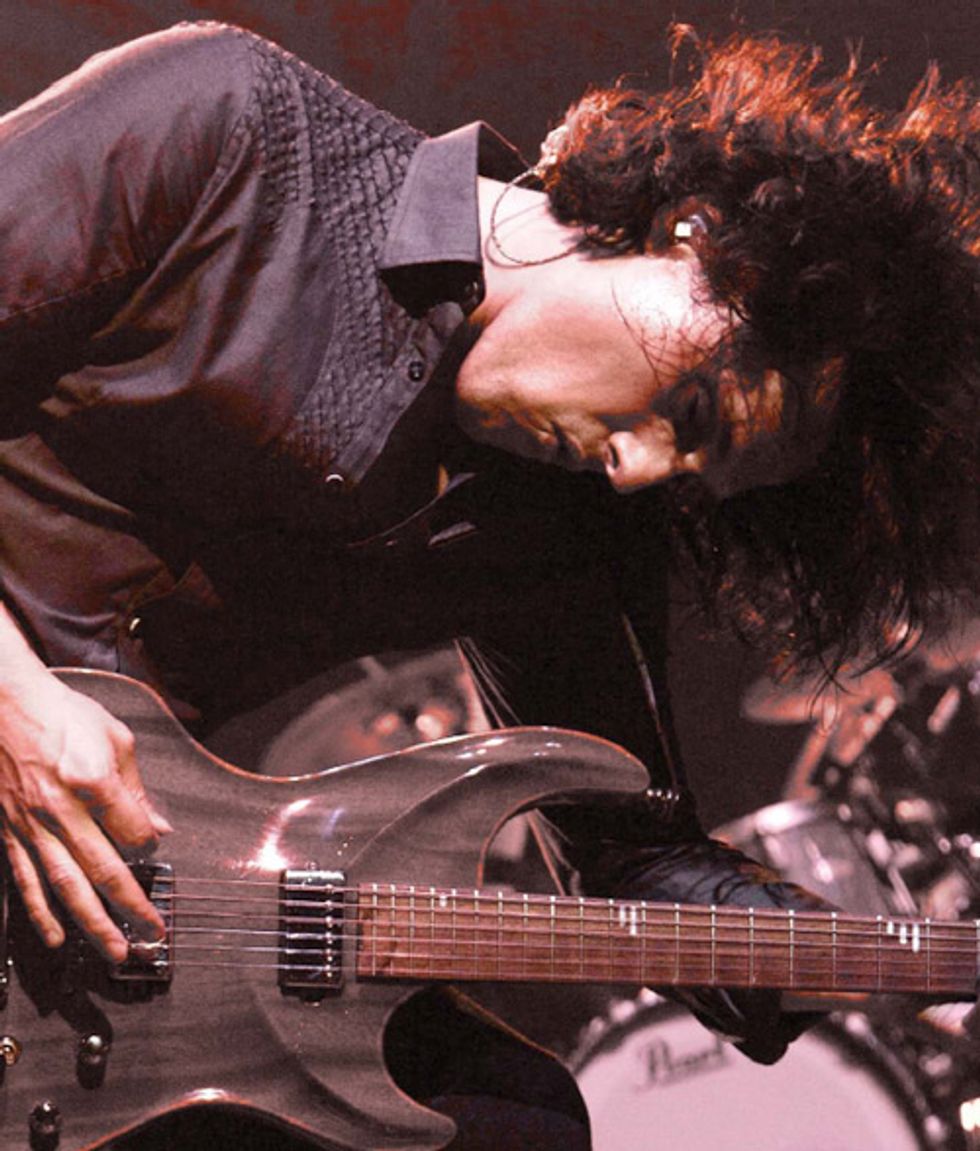

Joel Kosche onstage with one of his humbucker-equipped MJ Guitars. Photo by Joseph Guay

When Collective Soul suddenly found itself without a lead guitarist in 2001, the Georgia-based band with seven No. 1 singles to its credit didn’t have to look very far to find a perfect replacement. Longtime tech Joel Kosche was a formidable guitarist and singer/songwriter who not only knew the band’s gear and repertoire inside and out, but had also hot-rodded its amps to achieve the trademark guitar sound heard on songs like the 1993 breakout hit “Shine,” as well as on subsequent chart-toppers like “The World I Know,” “December,” and “Smashing Young Man.”

Kosche officially filled Collective Soul’s lead guitar chair in 2003, and he has since added his own sound—shaped equally by metal, progressive rock, and classical, and distinguished by masterful use of effects pedals— to the band’s radio-friendly repertoire. He’s also joining in the group’s writing process and even put his vocal talents to work on the sardonic “I Don’t Need Anymore Friends,” a highlight of Soul’s 2007 album Afterwords.

In addition to playing with Collective Soul, Kosche recently concluded three years of tracking for his debut solo album, Fight Years, which is available on iTunes and at CDBaby.com. The album’s 14 songs chronicle his experiences as a musician—from the frustrating years he spent toiling in Atlanta bands while painting cars and motorcycles to his rocky ascent to the spotlight. We spoke with Kosche about his musical evolution as a guitarist, songwriter, tinkerer, and amp builder, and in the process discovered secrets to some of the uncanny sounds he gets in Collective Soul and on his own.

Do you remember what first got you hooked on guitar?

I remember first getting excited about music when I saw Elvis playing guitar. There wasn’t a guitar in the house, so I—like so many other kids without instruments— used to walk around strumming a tennis racket. One year, my older brother got a guitar for Christmas, but he couldn’t really hang with the lessons, so the guitar just ended up staying in a closet. My buddies and I would sometimes beat on it, trying to play things like “Smoke on the Water” on one string, but none of us knew what we were doing. Then one day, someone’s cousin came over, tuned up the thing, and strummed some chords. That was the first time I’d actually seen anyone make music on the guitar right in front of me, and I knew right then that I wanted to get serious about music.

When time period are we talking here?

This was in the early ’80s—long before you had the internet and YouTube—so I got some Mel Bay books and started teaching myself how to play chords and scales. One day I saw Roy Clark doing this flamenco kind of stuff on Johnny Carson’s show. I didn’t realize that was any different from classical guitar—it’s all done with fingerpicking—so when I was 16 or 17, I started taking classical lessons at a local community college. That was a great experience— it really taught me how to look at guitar in a different way.

How so?

On the guitar, we don’t have to really think about the names of notes—we just move the same shape to a different fret to play in a different key. But when I started playing classical guitar, I began to read music. I learned what, say, a G chord looks like on the staff in different inversions. A lot of classical guitar repertoire was originally written for another instrument, like the piano, with all these simultaneous bass lines and melodies. So I learned a lot about how harmony works and how music is structured, and I learned to approach music for music’s sake and not to just play the same old boxes and patterns.

How did you get involved with Collective Soul?

|

How did you learn to work on guitars and amps?

My first electric guitar was a Japanese SG rip-off made of plywood that I bought for 10 dollars. Since it was so junky, it didn’t matter if I messed it up, so I used it to learn how to set things up as demonstrated in my little library of how-to books. Also, Eddie Van Halen was melting everyone’s face off when I was coming up, and everybody was copying him and building their own “super strats,” so naturally I had to make one, too. I bought the basic parts from Warmoth and took the body to my high-school shop class to route out the cavities for a bridge pickup and a volume knob. Later, I got into Steve Morse, so I routed out a neck pickup and a toggle switch. I put in a coil-tap switch and then took it out, painted the guitar about 10 different times, swapped out the neck—you name it—and learned a whole lot in the process. Later, when I was working with Collective Soul in the late 1990s, Ed had some old Vox AC30s that he brought out on the road. They were constantly blowing up, so that became the catalyst for me learning how to repair and modify tube-amp stuff.

How did you teach yourself that stuff?

Through trial and error and using books like Gerald Weber’s A Desktop Reference of Hip Guitar Amps and Aspen Pittman’s The Tube Amp Book. For me, those books were like finding the damn Dead Sea Scrolls or something! [Laughs.]

What was it like to transition from being the group’s tech to being their guitarist?

The band called me out of desperation in 2001 when they had parted ways with another guitarist. In less than two weeks, they were going to travel to Australia to play at the Goodwill Games in Brisbane, and then on to New Zealand for more shows. I had, like, 10 days to learn lead parts for the entire set and put together a touring rig. I was finally getting paid to play guitar, but it wasn’t all happy fun. After the tour, we came back to the US on September 10—the day before 9/11—and all our Northeast shows were cancelled. Things felt very unsettled for a while, but we finally got into a good groove and I permanently joined the band in ’03. Things have been pretty busy ever since.

While many Collective Soul songs come from the pen of Ed Roland, you wrote and sang lead vocals on “I Don’t Need Anymore Friends.”

Yeah, I recorded that one with a batch of songs that ended up on my solo record. When we made Afterwords, Ed asked if I’d like to contribute a song, so I picked one of mine that I felt would be most appropriate for a Collective Soul record—something somewhere between poppy and rock-guitar-riff oriented. It was pretty close to being finished when I brought it in—it just needed some bass lines and background vocals. Lyrically, it’s just a nice little song about how I felt at the moment. We were out on tour a few years ago, and we were at this party the promoter threw for us after the show and . . . what can I say? I just didn’t want to be there! I get sensory overload sometimes when there’s too much going on and too many people talking to me at the same time. It makes me withdraw. The lyrics are really supposed to be kind of sarcastic and are not to be taken literally—with the music business being what it is, I need all the friends I can get!

Some of the guitar parts on that song are so synth-like. What sorts of effects did you use to get that sound?

I’m a big fan of the old DigiTech Whammy pedal, and I always wind up stumbling on some cool new sounds when using it in conjunction with other pedals. For the second half of the first verse, I played a P-90-equipped MJ guitar and set my Whammy to an octave-up, octave-down sweep and ran that through a Leslie-type pedal—an Option 5 Destination Rotation—and a Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler. I set the amp fairly clean and then got those keyboard-sounding things by rocking the pedal back and forth between the octaves while I played the Bm–A–G– D–A chord progression.

Is the MJ your main guitar?

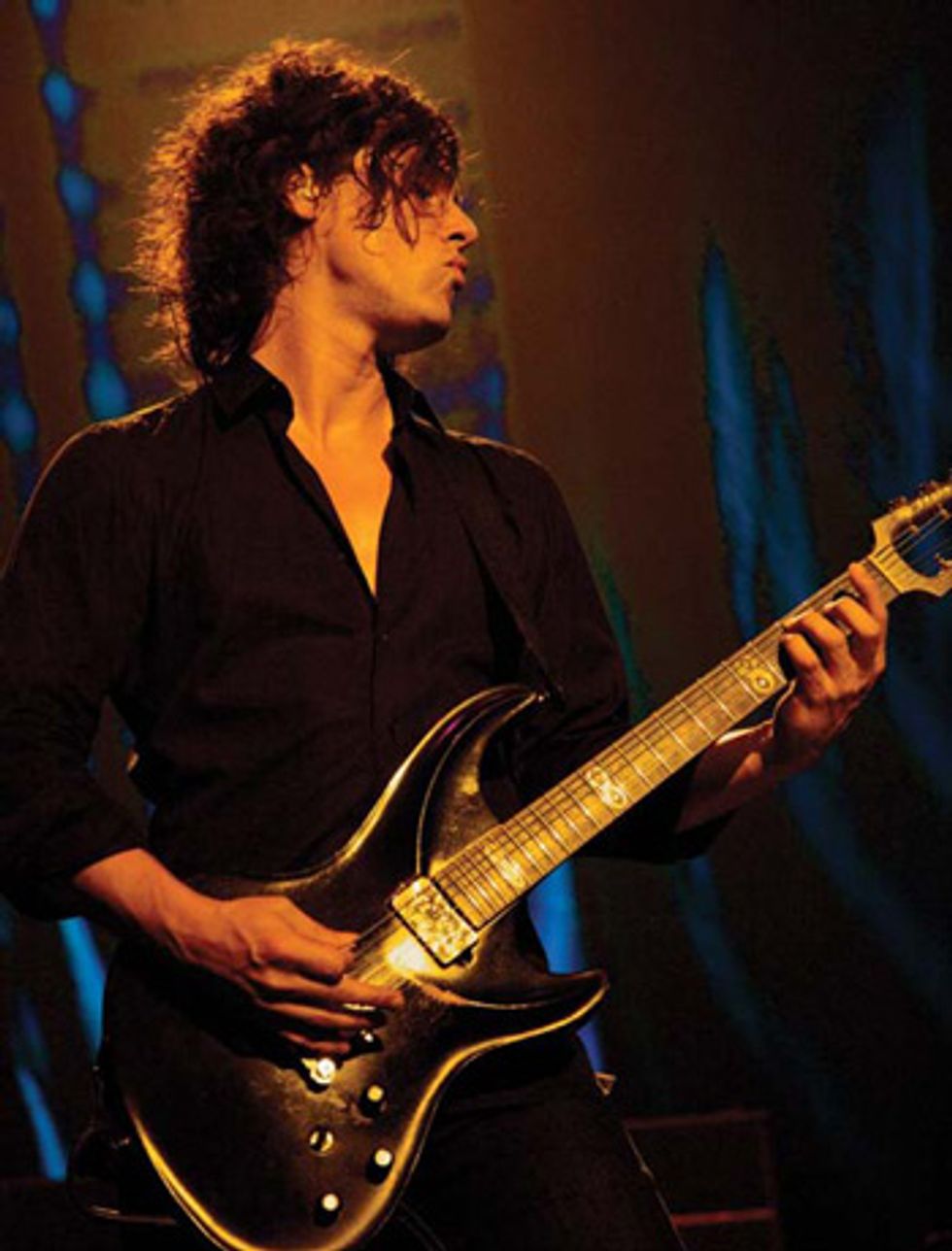

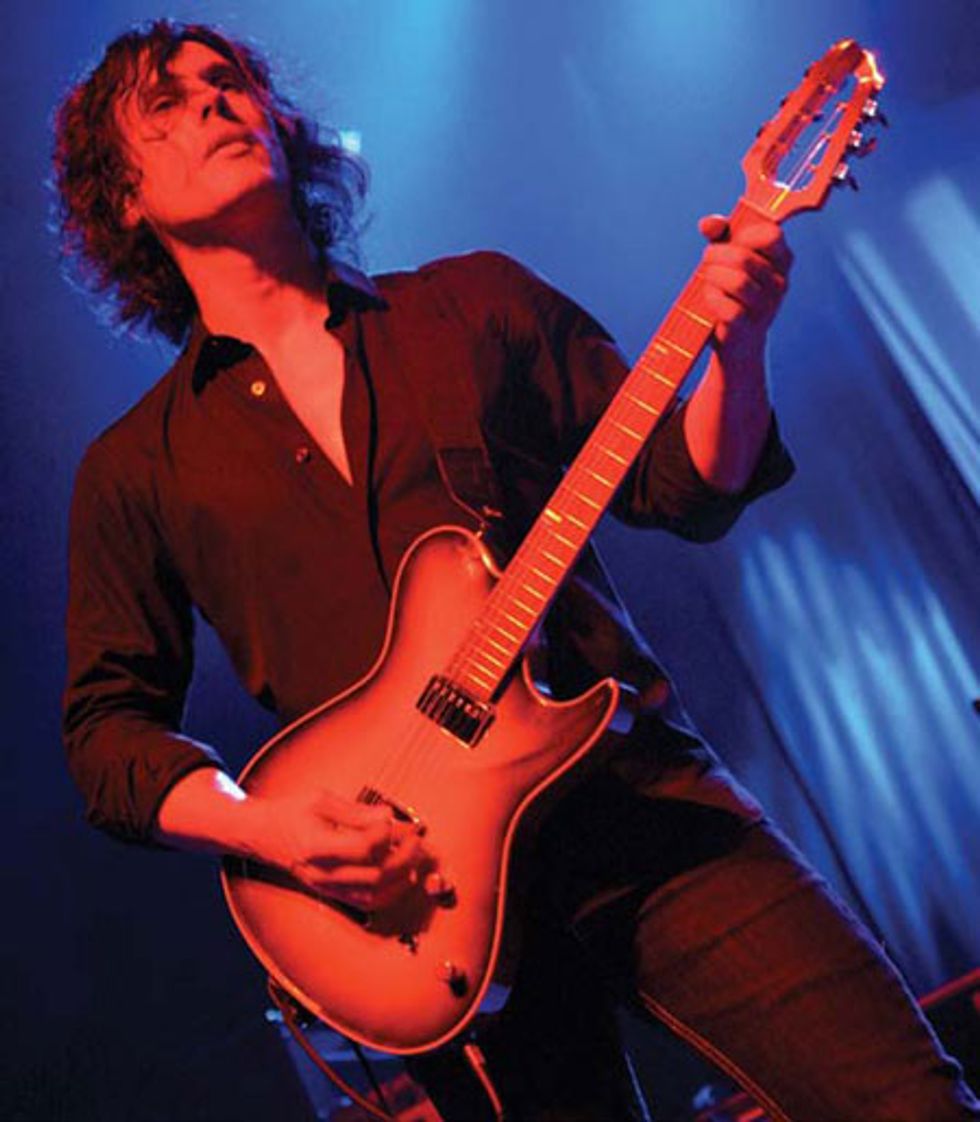

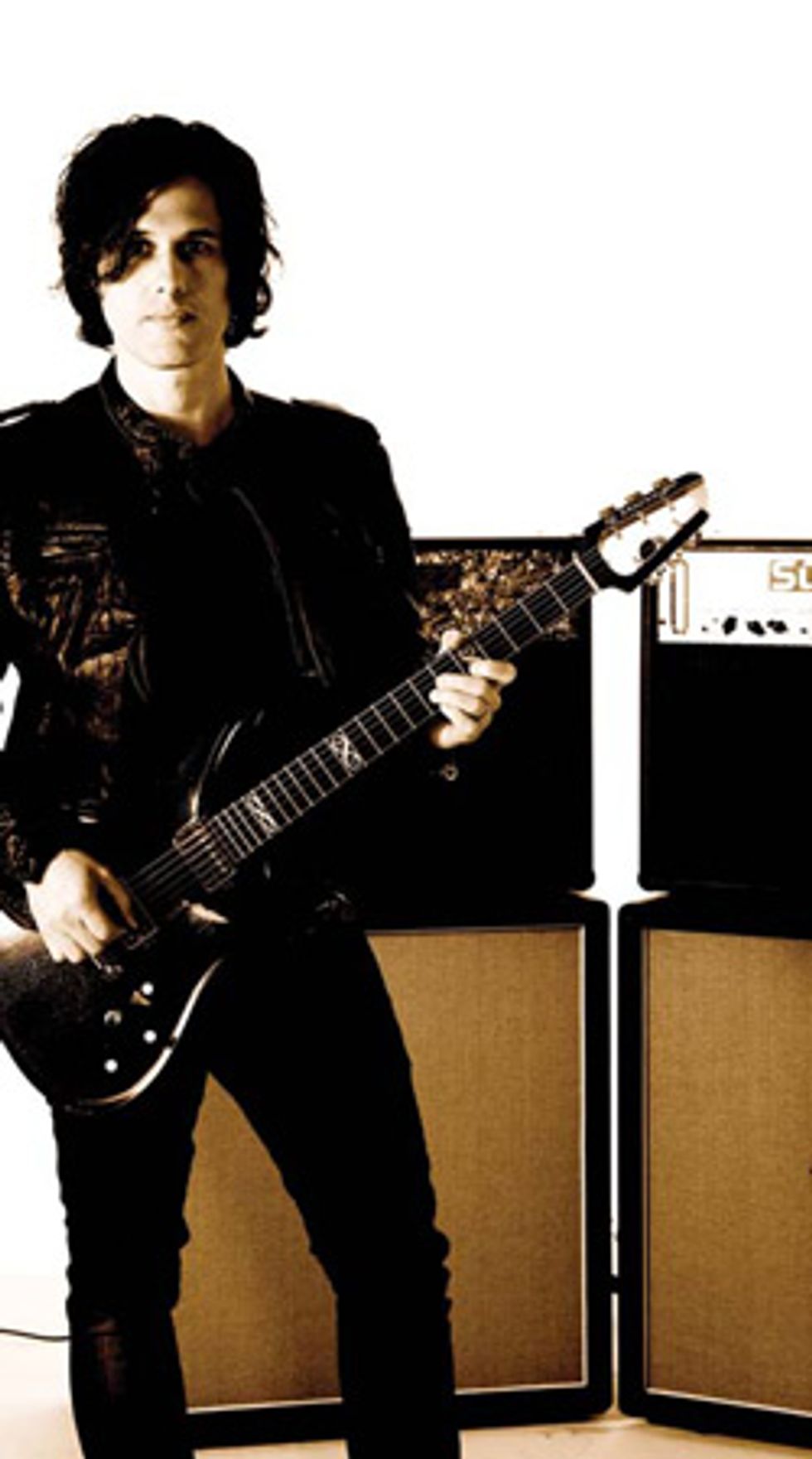

Yes. I have a few that I play both in Collective Soul and on my own. I own that one MJ Mirage outfitted with P-90s, and it’s become one of my very favorite guitars for recording, especially lead lines and melodic parts that I want to stick out a bit more. It’s an all-mahogany, chambered-body guitar with a rosewood fretboard. I own six humbucking- equipped MJs and another that’s more in the Tele style, as far as electronics go. They’re all great, and each one has its own personality, but my favorite is a beat-up black one that’s all mahogany with an ebony fretboard. I asked [MJ owner] Mark Johnson to do a thin, satin-black finish directly on top of the wood—without any clear-coat protection—so it’s taken some lumps out on the road.

What other guitars do you play?

I’ve got a few PRS McCartys and two Soloways. One is a 6-string Swan that has a cocobolo top on a swamp ash body. The other is a 7-string Swan with a swamp ash body and a black lacquer finish. Those Soloways are really cool for drop tunings because of their long 27" scale, and they hold together nicely under distortion. I think Jim [Soloway] is kind of a jazz guy, so it’s funny that I use his instruments for the big rock stuff.

Which songs do you use your Soloways on?

I used the 6-string with great results on “Sunrise” from my solo record. I used the 7-string on “Caterpillar,” “A Steel Cage to Ride,” and “New Song”— basically anywhere I could find an excuse to play it!

What sort of amps do you prefer?

Onstage, I use a pair of Vox AC30s for clean stuff, and for dirty stuff I play some Splawn amps—a Nitro and a Quick Rod through Splawn 4x12 cabs loaded with Eminence Greenback-type speakers. I love Splawn amps. They’re made at this small shop in North Carolina and have a great hot-rodded Marshall type of sound. In the studio, I use an amp I built myself. It’s basically a Marshall and an AC30 all in one. It sounds like a huge stack, but it’s only 30 watts.

Photo by Joseph Guay

Can you tell us a little more about the homemade amp—it sounds intriguing.

I’ve actually built four of them now. Basically, each one is a two-input amp with one side being pretty much a top-boost Vox AC30, and the other side being sort of a hot-rodded Marshall with some preamp gain. The hot-rodded side has a tube-buffered effects loop and a Master Volume. Both channels feed into an AC30-style power section with a few tweaks here and there, but basically it’s a four- EL84, cathode-biased power section with no negative feedback. It’s a 30-watt combo, but most of the time I run it through a 4x12 Splawn cab. Component-wise, I’ve used anything and everything, but I tend to go with carbon comp–type resistors on certain parts of the circuit and metal-film everywhere else. I’ve used SoZo coupling caps for the most part, but I’ve used Orange Drops, too. As for tubes, I think the JJ brand sounds best overall for what my amps do.

Did you build everything from scratch?

I did, except I had a guy weld the chassis together for me. I wanted the chassis to be unique, so I couldn’t use off-the-shelf parts. I basically took my drawing to a local sheet-metal shop and had it made, and then I drilled all the holes myself and had it powder-coated. I’m into woodworking, so the cabinet part was easy and fun for me. I drilled and punched all the turret-board stuff myself. And, of course, I wired it up myself.

How do you get such consistently killer dirty tones?

I find that when I use a distortion pedal, it tends to thin out the sound. I’m really just looking for more sustain, so I’ll usually step on a compressor before I step on a distortion. To get a gritty sound, I like to set my amps pretty loud and filthy, and then back off my guitar’s Volume control to get something a little cleaner. But occasionally—for instance, on a song like “Fuzzy”—I do use a Z.Vex fuzz pedal. To be honest, I can’t remember which one, but it’s a pretty cool pedal. It can get crazy if you want it to, but I set it up to be very ballsy and smooth at the same time.

There are so many great guitar moments on the record, but the multilayered parts on “Yours to Reap” really stand out. How did you record that?

Everything was done with regular guitars tuned a half-step down. Some of them were lowered to dropped C# tuning. I used the P-90 MJ guitar for every part except the solo, on which I played my trusty black MJ. The main part that opens up the song and becomes the sort of fake keyboard-pad sound is this: four tracks of guitars, each played with an EBow going through a Whammy pedal set to drop two octaves when I step on it, through some delay and then through my homemade amp. The main little riff that comes in eventually is done with my Option 5 Destination Rotation pedal through some delay and then through my amp with a fairly clean sound and the bass rolled off a fair bit to make it a little lo-fi—so that everything around it sounds bigger. After the vocal finishes, a little string-quartet thing comes in and that’s done with four guitars, each played with an EBow going through a Whammy pedal. The solo was just the guitar through the homemade amp with a little delay.

Describe your general approach to writing.

It’s nothing mind-blowing. It almost always starts with me tinkering around on whatever guitar I have at hand, coming up with a new riff or chord progression, and singing along with a melody. Later, as I’m lying in bed or driving in my car, I might find myself humming a familiar tune, only to realize it’s one I recently composed. If it sticks like that, the song is generally a keeper. As for lyrics, I’m not trying to blow anyone’s mind—I’m just trying to articulate exactly how I feel. That can be tough, because so many of my lyrics are intensely personal.

How does your classical training factor into your music these days?

I often find myself using hybrid picking even when I don’t have to, and I think that’s a technique leftover from playing classical guitar. Also, I still play classical in order to keep my chops up. I have a handful of pieces that I first learned years ago— things like Bach’s “Bourrée in E minor” and “Ave Maria”—that I’m still chipping away at. Talk about music for music’s sake! “Ave Maria” is a great one—the chords are ridiculous. It really expands your playing to work through such beautiful chords— the sort that you wouldn’t normally think to play.

Are there any new guitarists out there who inspire you?

|

Joel Kosche’s Gearbox

Guitars

Assorted MJ Guitar Engineering Mirage models (one with P-90s, six with humbuckers, and one with Tele-style electronics), one 6- and one 7-string Soloway Swan, assorted PRS McCarty models

Amps

Two Vox AC30 Custom Classics, Splawn Nitro head, Splawn Quick Rod head, Splawn 4x12 cabinets with Eminence speakers, homemade SugarFuzz 30-watt tube combos

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball 2215 6-string sets (.010–.052), Ernie Ball 2621 7-string sets (.010–.056), Dunlop Ultex Sharp .73 mm

Effects

Ernie Ball Volume Pedal, DigiTech Whammy, Morley Bad Horsie 2 wah, Boss AW-3 Dynamic Wah, Boss OC-3 Super Octave, MXR EVH 90 phaser, Rocktron Replifex, Rocktron MultiValve, Heet Sound EBow, Line 6 Echo Pro, Option 5 Destination Rotation, Z.Vex Vextron Series Mastotron fuzz, Keeley Compressor

Miscellaneous

Two Voodoo Lab GCX Guitar Audio Switchers, Voodoo Lab Ground Control Pro Programmable MIDI Foot Controller, Voodoo Lab Pedal Power 2, Boss TU-12 tuner, Furman PL-Plus Power Conditioner and Light Module, Furman PL-Plus D Power Conditioner and Light Module

Although Kosche also uses MJ Mirage guitars with P-90s and Tele-style electronics, he tends to favor humbuckers for his live guitars. Note the subtle differences: The two leftmost guitars’ pickups are screwed directly into the body, the two outer guitars have wraparound tailpieces, and all have Volume knobs for each pickup, a Tone knob, and a 3-position pickup selector switch—except for the pickguard-outfitted model, which has a Badass bridge, a single-coil in the middle position, Volume and Tone knobs, and a 5-way pickup selector. Kosche’s live amps include two Vox AC30 Custom Classics (top right) for clean tones and Splawn Quick Rod (top left) and Nitro (bottom left) heads driving Splawn 4x12 cabinets with Eminence speakers. The amps are plugged into a Furman PL-Plus D Power Conditioner and Light Module.

Kosche’s favorite guitar is a mahogany-bodied MJ Mirage with an ebony fretboard and a thin black finish with no top coating. “It’s taken some lumps out on the road,” he says.

Kosche only keeps a Boss TU-12 tuner, his Voodoo Lab Ground Control Pro MIDI controller, his Splawn Quick Rod head’s channel selector, and treadle-equipped pedals like his Morley Bad Horsie 2 wah, DigiTech Whammy, and Ernie Ball Volume Pedal onstage. He powers it all with a Voodoo Lab Pedal Power 2.

Kosche’s rack includes (top to bottom): a Furman PL-Plus Power Conditioner and Light Module, a Rocktron MultiValve, a Line 6 Echo Pro, a Rocktron Replifex, two Voodoo Lab GCX Guitar Audio Switchers, and a pedal drawer containing a Voodoo Lab Pedal Power 2 (just out of view) driving a Boss AW-3 Dynamic Wah, a Boss OC-3 Super Octave, a Keeley Compressor, a Z.Vex Vextron Series Mastotron, and an MXR EVH Phase 90.

The SugarFuzz combos that Kosche designed and built himself from scratch—including everything but chassis welding—feature a top-boost AC30-style clean channel labeled “Sugar” and a hot-rodded Marshal-type channel labeled “Fuzz.” The SugarFuzzes are driven by a quartet of EL84s and have a Master knob, independent Volume knobs for each channel, and shared Bass, Treble, and Cut controls.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)