From the runaway success of Creedence Clearwater Revival to his transcendent 1985 solo album, Centerfield,and beyond, life has been a long, strange trip for John Fogerty. But as he recounts in his new tell-all memoir, Fortunate Son: My Life, My Music, even during the dark days he always found clarity in music, family, and of course his gift for coaxing memorable riffs from a guitar.

If there’s one thing Fogerty loves almost as much as singing and playing music, it’s the thrill of discovering a great song. Even today, he describes hearing Dale Hawkins’ “Susie Q” on the radio with the same wonder and elation he felt back in 1957, when he was a 12-year-old kid banging out the rhythm on the dash of his mother’s car in the San Francisco suburb of El Cerrito.

“That’s why I call ‘Susie Q’ a ‘dashboard banger,’” Fogerty says. “Back in those times, a car’s dashboard was made out of metal, so it made a hell of a racket when you beat on it. And ‘Susie Q’ just drove me into a frenzy. I couldn’t even believe how primitive and tribal it was. I was just gone.”

He didn’t know it then, but the song’s infectious riff and skillet-hot solo were played by a young Telecaster whiz named James Burton, who would go on to back Ricky Nelson on a string of rock ’n’ roll hits, including “Be Bop Baby,” “Hello Mary Lou,” “Stood Up,” and “Waitin’ in School.” With his confident hybrid-picked style and tube-warmed rockabilly sound, Burton exerted a profound influence on everyone from Keith Richards to George Harrison to Joe Walsh.

A little more than a decade after first hearing “Susie Q,” Fogerty would channel his youthful excitement into a funky, quasi-psychedelic “swamp rock” arrangement of the song. Creedence Clearwater Revival’s eight-and-a-half-minute version of “Suzie Q” (that’s right, spelled with a z) became a hit at San Francisco’s freeform underground rock station KMPX, eventually breaking the band into the Top 40 nationwide. With Fogerty out front—usually on his Rickenbacker 325—his brother Tom on rhythm guitar, Stu Cook on bass, and Doug Clifford on drums, Creedence played no-frills rock with a bare-knuckled conviction that was utterly unique in the Bay Area’s hallucinogen-fueled late-’60s scene. Now-classic albums like Bayou Country (with the anthemic standard “Proud Mary”), Green River,and Willy and the Poor Boys brought them instant adulation around the world—a party that, by 1972, ended just as abruptly in a blaze of recrimination and acrimony.

All this and plenty more makes it into Fogerty’s new memoir from Little, Brown and Company. The unvarnished and sometimes bittersweet autobiography often reads as much like a confessional as it does a celebration of a dyed-in-the-wool rock ’n’ roller’s life on the move. He details the breakup of Creedence, the long, arduous legal battle with Fantasy Records head Saul Zaentz over the rights to his own songs (and significant sums in record royalties), and how the fight nearly finished him before the mid-’80s sessions for Centerfield—widely considered his quintessential “comeback” album. But Fortunate Son also reveals the heart of a working-class romantic—one whose love for his wife Julie, whom he credits with saving him from an emotional meltdown, is inexorably intertwined with his devotion to music, and especially his lifelong fascination with guitar players.

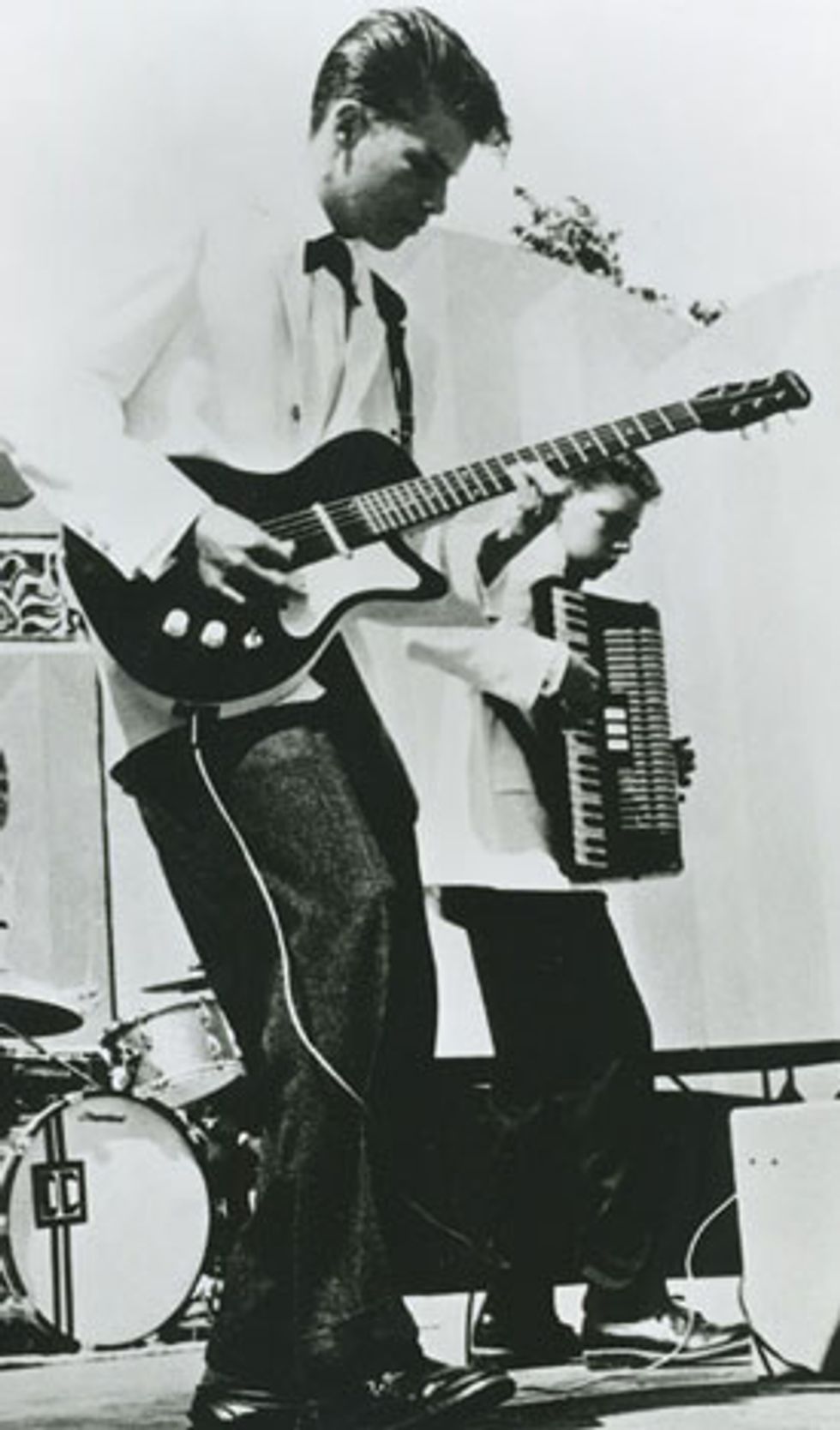

At the tender age of 14, a dapper Fogerty rips on his Silvertone at the county fair.

“That’s the wonderful thing with music, you know?” Fogerty says. “I’ve done my fair share of tracking down records. And it’s more than fascinating, because you’re like an archaeologist—there’s the reward when you discover some great stuff by Hank Williams, or you go back into the ’30s and find some great blues that you didn’t know about. It’s just such a thrill. I’m sure my wife worried that I was going too much in that direction for the book, but that’s certainly a big part of me.”

Having logged more than 50 years on the guitar, starting with a Stella acoustic and then a single-pickup Danelectro Silvertone (the first electric for countless young players in the late ’50s), Fogerty has never given up his passion to get better—or to explore new gear. He still owns a few vintage axes from his Creedence days, but he’s also become a bit of a shredder on his Music Man Axis and a recently acquired Ibanez RG920.

“My technical ability was deeply rooted in rock ’n’ roll and blues, and a little bit of country,” says Fogerty of “Green River” and other Creedence nuggets, “almost in the sense that I didn’t wanna get too good—because then I wouldn’t sound ‘rock ’n’ roll,’ you know? I mean, to me now, that’s a fallacy, because as I got older I just wanted to improve. I wanted to get really good. But before Eddie Van Halen, that wasn’t necessarily considered an admirable trait. Right around 1970, when [jazz-fusion virtuoso] John McLaughlin came along, it was like ‘He’s too far out there—there’s too many notes [laughs].’ The weird thing is, at the very same time, I loved [bluegrass innovator] Bill Monroe—who was an incredible player. He played all kinds of notes and used all his fingers, but somehow in that music it was okay in my book. To me, it was more important to be emotional—to say it in a simplistic way, just hitting one string a certain way, like Albert King or B.B. King, or any of the Kings, because it was all about the tone and the rhythm of it. That’s what I was after.”

That tone is undeniable in Fogerty’s early work with Creedence. You can hear it in the low vibrato rumble of “The Midnight Special,” which Fogerty played on a Les Paul Custom tuned down a whole step to standard D and plugged into a Fender Vibrolux. (“To me, that was the holy grail. When I heard that sound I just went, ‘That’s it!’ And it’s still it.”). On “Green River,” a Burton-flavored, hybrid-picked twang comes through on the song’s opening riff and in the solo, with the Rickenbacker ringing out through a 100-watt Kustom K200A-4 amplifier, which Fogerty almost always had with him onstage.

Many years later, that tone is still being chased by budding young axe-slingers, but Fogerty insists that then, as now, the best thing about his Creedence hits is their succinctness and simplicity. “I like to think my approach to writing on the guitar was more mystical, like Booker T. & the M.G.’s,” he says. “It was simple, but it was right. So if you played that part when you were playing that song, you sounded just like the record, you know? I thought that was the real secret to what Creedence was doing: A kid could sit down and listen to ‘Proud Mary,’ and if you learned that opening riff, you just about had the whole song.”

Fogerty’s only words for this pic of him raging onstage with a Les Paul during CCR’s heyday are “ROCK and ROLL!”

As you started crafting a style of your own and making an impact as a singer and songwriter in the early Creedence days, how strongly did you consider yourself a guitar player?

Well, at the time I thought I was pretty good [laughs]. Put it this way, I admired Chet Atkins greatly, and James Burton of course—and many others—but those are two guys that I would think about and talk about all the time. I considered Chet the best guitar player on earth, and I didn’t think of myself as being anywhere near where he was. It’s a weird thing that your brain does—especially when you’re younger: You don’t realize you’re doing it, but you close doors and you tell yourself, “I won’t be able to do that.” You kind of set yourself off. Eventually I got past that way of thinking, though.

In Fortunate Son, you mention that one of your strengths is being able to recognize a great riff. But you also seem to have a prominent awareness of the groove—a sense of pocket.

Thank you for that. You know, every once in a while, sort of by accident, I’ll stumble on some new little riff, and invariably it’s not because of how complicated it is—it’s because of that groove that makes you feel good. It’s the same exact thing as discovering the “Green River” riff way back when. You get into it, and it’s so simple, but it just feels really good. Most songs that I write, I feel better when there’s a pocket to the arrangement that gives you a happy and soulful feeling.

The Creedence version of “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” works like that.

I do happen to think that’s one of the great strengths of Creedence as a band. We were able to—in the good times, of course—find that groove. That was essentially my job as the arranger. I had Marvin Gaye’s version, and I knew Gladys Knight’s version, and somehow in the working of it, one day I had the epiphany that instead of being an electric-piano song, it could be a guitar song. It was like, “Oh man, this is a cool riff!” From that moment on, I was off.

None of us were technical whiz-bangs, you know? But since Booker T. & the M.G.’s were our idols, I didn’t really think of them that way either. The sound they made together was a really good groove, and I thought then—and for the most part I still think this way—that was much better than seeing some flashy guy playing nine million notes, with the band behind him just for backup. I always thought the idea of a band grooving was a far more powerful statement.

nine million notes.

Your choice of guitars has changed quite a bit since Creedence. You started with the Rickenbacker, a Gibson ES-175, and a Les Paul Custom. You picked up a Telecaster to record 1973’s Blue Ridge Rangers, and then a Washburn Falcon for Centerfield? What drew you to the Falcon?

Well, it was some time during the “hot rod” days in the middle to late ’70s, and you were seeing pickups without covers everywhere. DiMarzio and Seymour Duncan were getting popular, and in my own fumbling way I was intrigued with all that. I’m pretty sure it was Leo’s Music in Oakland where I went and tried a bunch of different guitars, and I remember picking up the Washburn in that store. The pickups sounded really hot, especially on the bridge pickup. I think I was intrigued too because it had a through-the-body neck. That was very culturally correct at that time—you know, it gives you more sustain. I think it had brass hardware on it, and it had those pickups, but the neck and everything else was perfect. You could get a lot of different sounds out of it. At the time, I really thought that was gonna be my guitar for the rest of my life—at least for the Centerfield album, and certainly on “The Old Man Down the Road.” When I toured in ’86, I played it quite a bit.

You came back to a Telecaster for a while recently. Why did you stay away from them for so long?

I always thought they were kind of hard to play. I would say that—even now, after all these years—that assessment was correct. A Telecaster didn’t give back all that sustain and amp-driving tone that a Les Paul did through a Marshall. Nobody had pedals back then, so if you wanted to get a good sound out of it, you had to learn what all the country guys like James Burton were doing. They had a whole other approach to playing guitar. It was a different style from Jimmy Page or Eric Clapton, at that time at least. It would sustain forever if you hit a low string, but if you hit a chord, the notes didn’t ring very long at all. Also there was more space between the strings than the typical Gibson setup. And again, it’s a 25 1/2" scale rather than 24 3/4". But if you really want it badly enough, then you’ve gotta put in the time. When you do, you’ll be rewarded, because there’s nothing that sounds like a Telecaster doing that stuff. I mean, I just get a smile on my face.

Fogerty's Primary Gear Circa 1968

GuitarsRickenbacker 325

Gibson ES-175

’68 Gibson Les Paul Custom

Amps

Fender Vibrolux

100-watt Kustom K200A-4

a

Kustom 2x15 cab

Fogerty's Primary Gear Circa 2015

GuitarsIbanez RG920

Fender Custom Shop Telecaster

Bill Crook Paisley T-style

’68 Gibson Les Paul Custom

’69 Gibson Les Paul goldtop

Custom “Louisville Slugger” guitar

Amps

Cornford MK50H (modded to 100 watts)

100-watt Diezel VH4

Custom Ampeg 2x15 cab

Dr. Z Z Wreck

Effects

Moog Minifooger MF Delay

SolidGold FX Surf Rider

Custom Zeta Systems tremolo/vibrato

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Hybrid Slinky strings (.009-.046)

You picked up a Dobro again for a few cuts on Blue Moon Swamp [1997]. Had you played that since Creedence’s “Looking Out My Back Door”?

No, and for that song all I had learned was a very simple little part, and rehearsed it just enough so that I could record it. I first got introduced to the Dobro backstage at a Johnny Cash show in 1969, by the wonderful [late bluegrass player] Tut Taylor. There was this strange hippy kid who had been hanging around, and he says, “I can get you one of those. I know where there’s a whole bunch of them.” Eventually he found the one you see on the cover of Green River—it’s a Regal Dobro, as a matter of fact, and that strange hippy kid was George Gruhn [laughs]. I think I was right there at the beginning of his business, which was pretty cool.

But I put the Dobro away until about ’92. I started taking trips to Mississippi, and I think that’s when I really got reacquainted with Dobro. When you spend time there, it almost seems like the earth is buzzing. There’s electricity in the ground. I definitely sense that energy. So that sense of a drone—that bluesy, buzzing thing—was in me. At first I started playing normal slide. I got hold of a resonator guitar with a Spanish neck, and just walked around the house playing it. I did that for a year or so, but it wasn’t quite right. And then one day I was at a guitar show out in Pomona [California], and I bought a Dobro from a guy there, tuned it Dobro-style to G–B–D–G–B–D, and started taking it with me on those trips. That’s when I came up with the riff that’s on [2004’s] “Joy of My Life.” I knew it was original, and I really liked it.

And you know, because I talk about tracing things backwards and trying to figure out where they start—well, all Dobro roads, when you’re really serious and trying to learn, eventually lead you to Jerry Douglas. Once I heard his records, with his great tone and his vibrato and his technical ability and musical taste, eventually I realized he’s my favorite musician of all time. It just thrills me when I hear him play.

You write about how the new track “Mystic Highway” [from 2013’s predominantly covers album Wrote a Song for Everyone] was important for you. And throughout the book a lot of your sentiments on experiencing music—and even writing songs—involve riding in a car. It’s almost like the movement, the journey, is an integral part of your work.

I think there’s some truth to that—and you know, a car is also a perfect listening space. I know people with home setups make a big deal about sitting in the right spot—and even in the studio, you’ve gotta get that chair right between the two NS-10s [Yamaha monitors] or whatever [laughs]. But in a car it’s just perfect because the air is sort of trapped. And one of the secrets of good producing is to arrange your records for a car. You don’t need so much—just a backbeat, a vocal, and on my records at least, you need a guitar. Then the things you have right in the middle, sonically, they should probably be the loudest. So while you’re singing, the guitar shouldn’t be as loud as you are—but when it goes to the solo, that should drive the whole thing. You don’t need to hear a symphony orchestra. With just a really cool guitar part and a backbeat, you’ve got it all—especially in the car.

Keep on Burnin’

Don’t bother mentioning old dogs and new tricks to John Fogerty—he doesn’t want to hear about it. Over the last decade or so, he’s been woodshedding, watching guitar videos online, and picking up new techniques with the appetite of a hungry disciple. For proof, take a look at this live clip of the Creedence staple “Keep on Chooglin,’” from his 2005 concert film, The Long Road Home.With his dive-bombing whammy bends and neo-classical tapping techniques, Fogerty doesn’t quite take Yngwie Malmsteen to task, but the fact that he even makes the attempt and comes off sounding like a real shredder is testament to his dedication.

“It’s a funny thing,” he says today. “If you latch on and just stay current, then you’re not out of it anymore. Back in my dark period, I was adrift—cast off the ship like Captain Bligh, in my little rowboat trying to find land [laughs]. But once you get back into it and just stay current, it’s really effortless—especially online. I’m constantly getting lessons. You just go on YouTube and that will lead you from one thing to another.”

Fogerty also cites his renewed interest in Eric Johnson, as well as players like Rick Graham, as sources of inspiration. At the same time, he’s been refocusing on his Telecaster chicken-pickin’ technique, turning to the work of Johnny Hiland for guidance.

“Usually I just put my Ibanez [920] on the bridge pickup and play all my Tele riffs on that,” he admits. “I’m usually practicing at like 4 o’clock in the morning, so I have a Pocket Rockit [V2 headphone amplifier by C-Tech], which is really pretty remarkable to help you practice. I feel like you always see some new thing and you’re just kind of filled with lust about it [laughs]. I think it’s wonderful to be able to keep yourself stoked and excited and passionate.”

And if you want the full lowdown on Fogerty's current stash of gear, you gotta watch the Rig Rundown we did earlier this year covering his and his son's live setup:

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)