This has been a year of firsts for Kim Gordon. From Kim Gordon: Lo-Fi Glamour, her first solo art exhibition at a North American museum (the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, no less), to No Home Record, her first-ever solo album, she continues to break new ground, even at age 66. Which is saying something, as she’s already spent 30+ years as a primal force in one of the most influential indie-rock bands on the planet. As bassist, co-songwriter, and sometimes vocalist and guitarist for the legendary Sonic Youth, Gordon logged 16 studio albums—including seminal post-punk/noise-rock works EVOL, Daydream Nation, Goo, and Dirty—six live albums, nine EPs, and a mind-boggling array of experimental/instrumental releases on the band’s Sonic Youth Recordings label, not to mention official bootlegs, tribute performances, and soundtrack contributions. Of course, there were all the attendant world tours, magazine interviews, and television appearances, too.

Viewed in that light, perhaps it should be no surprise Gordon continues to push the envelope—even if her new album wasn’t even intentional. At least not at first. “I just really hadn’t thought of doing a solo record, but I kind of accidentally did some work with Justin,” she admits with a chuckle.

She’s referring to Justin Raisen, her primary collaborator and producer on No Home Record. “Justin had another project that he wanted me to sing on and, eventually, he sent me something that I thought, ‘Okay, I could make lyrics for this and add to it.’ And that came out pretty good.” That project was singer-songwriter Lawrence Rothman’s 2016 single “Designer Babies.” Afterward, “Justin was just always, like, ‘If you ever want to record some more or whatever….’”

Raisen, however, seemed to have a plan. The producer—who’s carved out a name for himself working with notable artists such as Charli XCX , John Cale, Ariel Pink, and Angel Olsen—gently coaxed new music out of Gordon by way of the Rothman session. For starters, he took leftover bits of Gordon’s vocal performance from “Designer Babies” and edited them together with what she calls a “trashy drumbeat” and sent it along to see what she thought.

“I really liked it,” she recalls. “So, I went back and did more vocals and added some guitar and that became ‘Murdered Out.’” Originally released as a single in 2016 but also the fourth track on No Home Record, this meditation on Los Angeles car culture—which is powered by a hooky, danceable groove by Warpaint drummer Stella Mozgawa—was a definite musical departure for Gordon. It’s also the first song ever released solely under her name. Perhaps because it was so different for her, musically speaking, “Murdered Out” also functioned as the catalyst for making a full LP. “It just kind of happened, slowly. It wasn’t a really big, premeditated thing, like, ‘Ooh, I want to do a solo record,’ you know?”

Perhaps the fact that Gordon hadn’t been plotting a solo record since the 2011 demise of Sonic Youth shouldn’t be too much of a surprise, either. The band’s breakup was monumental in and of itself. That it coincided with, and was admittedly a casualty of, the dissolution of her 27-year marriage to cofounding guitarist Thurston Moore, made it even more so. Sonic Youth wasn’t just another band. Sure, Gordon and Moore were the darling couple of indie rock, but they (along with cofounding guitarist Lee Ranaldo) were also musical trendsetters—now-iconic pioneers of a sound, attitude, and work ethic that were a pivotal influence on alternative music movements of the 1980s and 1990s. From their earliest albums—including their 1982 debut on Glenn Branca’s Neutral record label, ’83’s Confusion Is Sex, and ’85’s Bad Moon Rising—the band’s sound was an eclectic, electric combination born of the New York experimental no wave art and music scene. The three founding members’ use of alternate tunings, prepared guitars, feedback, and noise, literally transformed the way people listened to rock music. By the time Sonic Youth released 1990’s Goo, the band’s major-label debut on Geffen—which included the hit song “Kool Thing,” featuring Public Enemy’s Chuck D—they’d become the bona fide rock stars of the alt music scene.

To consider that Gordon might need some time to process these shifts in her personal and professional lives is reasonable. In reality, however, Gordon responded by delving into the visual arts. Her She Bites Her Tender Mind exhibit showed at the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin until November this year, and Lo-Fi Glamour ran from May to September this year, as well. She also wrote the 2015 memoir Girl in a Band, and cofounded the experimental, improv-based duo Body/Head with guitarist Bill Nace. Additionally, she moved back to her birthplace, Los Angeles, after several decades on the East Coast.

Is No Home Record the cumulative result of all these life changes and subsequent creative pursuits? While it does seem to perfectly reflect the zeitgeist, it also represents a personal evolution, bringing all aspects of Gordon’s multidisciplinary creativity together under one roof. Her preferred minimalist aesthetic—which permeates both her visual art and much of her bass playing in Sonic Youth—is adeptly channeled into the sparsely layered songwriting on No Home Record, a title that takes its cue from influential French-Belgian avant-garde director Chantal Akerman’s film, No Home Movie. Interestingly, whether it’s an intentional connection to the film or not, there’s a visual, cinematic element to the record as much as there is an aural one. There’s also an interesting collision of past musical influences, contemporary production paradigms, and present-day social observations on No Home Record. Songs like “Hungry Baby” draw on proto-punk elements of the Stooges, while “Cookie Butter” comingles with hip-hop, using the insistent nature of the tune’s drum loop to maximum effect. “Air BnB” melds Arto Lindsay/DNA-style noise-rock and guitar histrionics with lyrics inspired by a fascination with the bourgeois aesthetic of Airbnb listings. As Elaine Kahn writes in No Home Record’s liner notes:

“Despite the exhaustive nature of her résumé, the most reliable aspect of Gordon’s music may be its resistance to formula. Songs discover themselves as they unspool, each one performing a test of the medium’s possibilities and limits. Her command is astonishing, but Gordon’s artistic curiosity remains the guiding force behind her music.”

There are other collaborators on No Home Record, including Shawn Everett (Jim James, Alabama Shakes) and Jake Meginsky (L’appel Du Vide), but Raisen deftly curates it all, creating a continuity between the songs that contributes to the album’s storytelling scope. PG caught up with Gordon while she was on vacation, shortly after an appearance at the Warhol Museum for the conclusion of her Lo-Fi Glamour exhibit. The conversation was candid yet contemplated, sparse but revelatory, and occasionally interrupted by a bit of laughter.

Tidbit: No Home Record’s title is a nod to French-Belgian director Chantal Akerman’s No Home Movie, a 2015 documentary about Akerman’s mother, who was an Auschwitz survivor.

How did your No Home Record collaborations with Justin Raisen work? Did you give him material to work with beforehand, or were you crafting the songs together in the studio?

In some instances, I gave him materials to see what he would do, and then, on other songs, we built them in the studio. Before I actually thought I could work with him, I worked with Shawn Everett, another super-busy dude who kind of fit me in on his day off. Then, as it turned out, Justin had some time so we just kind of worked it that way. I’d never worked with a producer that way, so that was kind of interesting to me.

Your songs often sound somewhat improvised. How do you manage to maintain the spontaneity of your style within the structure of what a recording studio offers, or maybe even demands?

Well, a lot of it was improvised in the studio, but there are some things that are more straightforward. Pretty much every song was different. There are a couple songs where I recorded stuff at another studio and then sent it to Justin, like “Sketch Artist” and “Get Yr Life Back.”

Do the songs ultimately turn out the way you envision them, or do they morph as you navigate your way through the recording process?

I think “Sketch Artist” is probably the most different from what it started out as. But “Air BnB,” that was something that was an homage to Arto Lindsay’s guitar playing. So I’d play Justin different no wave songs to get the sense of rhythm that I was looking for, and he would have somebody play the drums, and then I did the guitar and then the vocals—maybe the bass would be last. They were all different.

“Cookie Butter” has a really cool groove to it. Did you come up with that?

“Cookie Butter,” which I did with Shawn, was based around a ’70s drum machine I borrowed from [Beastie Boys engineer] Mario Caldato Jr. I’d been fooling around at my house with that, adding guitar loops and stuff. I took that over to Shawn and we got good sounds for one of the rhythms and laid that down. Then I just had this idea of a two-part structure, and on the second part I just went for it on guitar—and maybe I did a second take of it. So it was kind of improvised—it starts out that way, but then gets kind of reined in or structured.

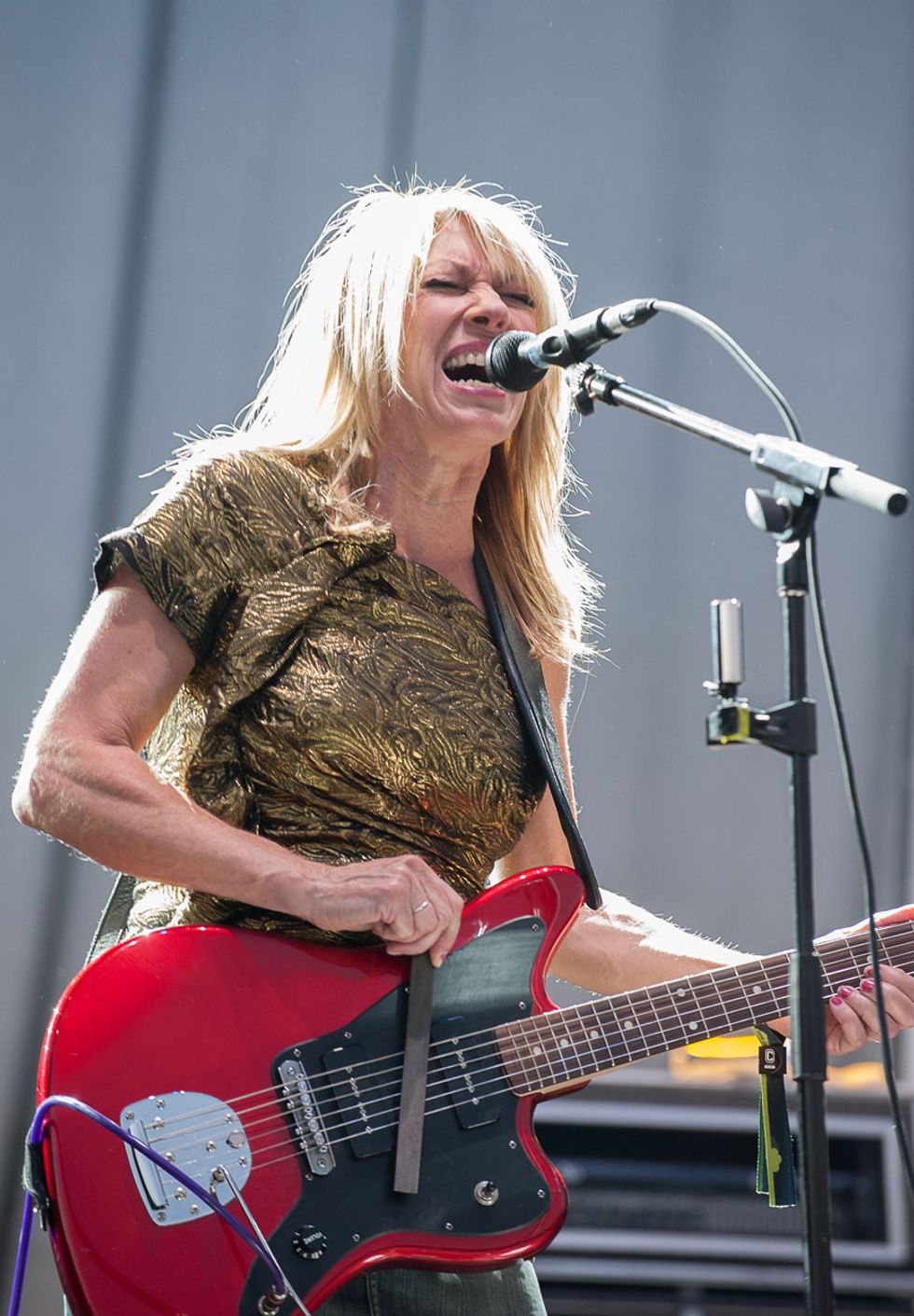

Gordon manipulates her Jazzmaster with a metal bar while playing with Sonic Youth at Austin City Limits in 2010. Photo by Jim Bennett

There’s a part in “Cookie Butter,” about four minutes in, that really captures a mood or atmosphere. It’s a quality that often permeates your music. Can you talk a little bit about your approach to capturing that kind of vibe on guitar versus playing a chord progression?

I really just came up with a sound and kind of rode it, you know? So what else is new? [Laughs.] I just wanted it to be as extreme as I could make it, but also have this rhythm going. I used these [ZVEX Effects] Lo-Fi Loop Junky pedals. I have a couple of those, and the Hendrix octave divider, but just to get extreme sounds.

To what extent does being a visual artist influence your songwriting? Do song ideas come to you visually, versus say, starting with a musical idea or motif?

Yeah, a lot of them do come to me visually. I get ideas for lyrics from driving around, looking at signs or hearing people’s conversations. “Air BnB” is referencing ideas I’ve been thinking about in artwork. That came from just looking online at Airbnb sites and being fascinated by these little modern landscapes—these utopian dreams that people can choose for a weekend. It’s kind of like curating your life for you in a certain way, so it’s kind of the opposite of what your home, and your life, is. This record, I feel like definitely my music is starting to merge more with my art practice in the sense of ideas for lyrics and things.

The music is sort of cinematic. I can see it almost as much as I hear it, if that makes any sense.

Oh, that’s cool. I do kind of feel they’re like little mini films or something. I would like to actually make a film someday. I love film as a visual medium, and Bill and I always think of Body/Head as soundtrack music, almost. I think my friend who wrote the press release [Elaine Kahn] said something interesting, like that my music isn’t something you so much listen to, as experience. Maybe she’s talking about this sort of dimensionality.

She also refers to your “resistance to formula,” which is interesting because we don’t live in an age, or even a society, that really encourages that. So much art seems formulaic these days.

Sometimes, though, I feel like people are more and more open to the unconventional. It’s almost like people are hungry for it. I don’t know. Maybe if it’s packaged the right way or something—you can brand anything.

Which leads to the question, When does resistance to formula risk becoming formula?

Absolutely. Everything can be branded. Weirdness is branded. Justin would always say, “Bring over your poetic fragments, we’ll make some music.” [Laughs.] He would elevate what I did because he’s such a talented producer, but at the same time he gets my aesthetic. So it turned out to work, because what I was bringing was so raw.

Is not playing bass a natural evolution of moving on from Sonic Youth and doing your own thing?

I haven’t played bass in, I don’t know, 10 years. For improvisation, guitar just works so much better for me. And, even in Sonic Youth, I was playing guitar more and more. I got tendonitis from playing bass the way I played it.

What instrument are you playing these days?

An old acoustic-electric Framus that has this amazing sound to it. But I just kind of use it playing solo more than anything—like solo improv. It’s just really fun to play.

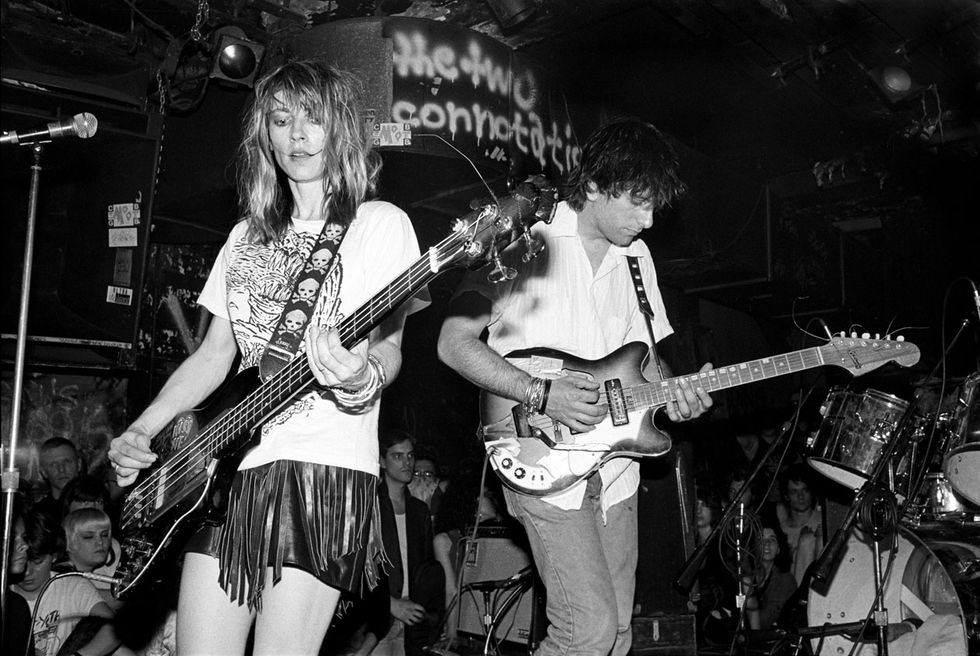

Gordon and Lee Ranaldo onstage with Sonic Youth at New York’s famed CBGB club in June of 1986, the same year the band’s EVOLwas released. Photo by Ebet Roberts

The finger piano on “Paprika Pony” is great.

I love the finger piano. That was Justin’s brother, Jeremiah. He came by and we asked him if he had any sort of cool beats, and he played us the one that became “Paprika Pony.” I did a vocal over it and put some low-feedback guitar on it.

“Earthquake” has the closest thing to a conventional chord progression on No Home Record.

It was pretty straightforward. I just played the guitar, basically. I think maybe it’s the closest to a classic song, in terms of structure. I didn’t intend that. It just came out that way.

You came to music a little bit later—you were in your 20s when you started playing bass. What attracted you to it as a way to channel creativity?

I started playing music with these two girls as a performance-art piece with my friend Dan Graham, and I played guitar [Editor’s note: Gordon is referring to the band Introjection with Miranda Stanton on bass and Christine Hahn on drums. Introjection performed in Graham’s “Performer/Audience/Mirror” at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design]. I didn’t really start playing bass until I started playing with Thurston. It was minimal and I didn’t know anything about music. I never studied.

Guitars

Framus acoustic-electric

Fender Blacktop Jazzmaster

Amps

Fender Hot Rod DeVille 2x12

Effects

Boss DD-3 Digital Delay

Boss GE-7 Graphic EQ

Dunlop Jimi Hendrix Octavio Fuzz

Dunlop Jimi Hendrix System Classic Fuzz

Dunlop TS-1 Tremolo Stereo Pan

Electro-Harmonix Deluxe Memory Man

Musitronics Mu-Tron C-200 Volume-Wah

ZVEX Effects Lo-Fi Loop Junky

Picks

Jim Dunlop light-gauge Nylon picks

So with a bass, it was the potential for minimalism that was inviting?

Yeah. I don’t really like busy bass lines. “Hungry Baby” is kind of an homage to the Stooges—the song “1970” [from the 1970 album Fun House.]. Ron [Asheton, Stooges guitarist] was made to play the bass on that record. I think guitar players make amazing bass players.

Are you improvising lyrically, as well as musically, when you’re recording a tune in the studio?

When I do vocals, I have some lines but I don’t know where it’s going to go. I kind of improvise as I’m doing the vocals, and I’ll add things in that aren’t written down. And then Justin would go back and edit it.

There was a lyric sheet included with the album’s press materials, which is unusual.

Yeah, they’re important—although some of them were hard to decipher [laughs]. I ad-lib stuff in the studio and fill in the blanks afterwards. I do music first, and then production, and then if I’m struck by the lyrics I’ll work on those. Some people are just into the lyrics, but usually they’re nonmusicians. I, of course, love a great lyric, but I don’t think my lyrics are particularly great—they serve the purpose of the idea. I would never think of myself as a wordsmith, put it that way.

Some of the beats on No Home Record are reminiscent of hip-hop. Is that one of your influences or was it something Justin brought to the table?

It’s definitely an influence of mine. In fact, one thing that kind of motivated me to want to do a record was hearing that big Cardi B hit “Bodak Yellow.” Before it was a hit, I heard it in this small club. My friend was DJ-ing, and I was like, “Whoa, who is this?” I thought it was so cool. I liked the minimal, punky feel to it.

Did you ever have any concerns about continuity between tracks from three different producers?

Not really. There was another song I did with Shawn that didn’t really fit the record’s moods. It was too long, so I might put that out as a separate thing at some point.

Between No Home Record, your visual-arts work, and all your other interests, you’re clearly a very busy person. Do you think we’ll see another solo album anytime soon?

I don’t know. I didn’t really intend to take on another thing. No Home Record just sort of happened. Every now and then I think, “Oh, it might be cool to do, like, a weird jazz record or something.”

Swaggering bass, shrieking guitars, and trippy vocals rule the day in the video for the original version of “Murdered Out,” Kim Gordon’s first-ever solo single.

For a spellbinding example of Kim Gordon’s experimental-improv guitar work, check out this 2018 Body/Head performance at the Philadelphia Mausoleum of Contemporary Art.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)